Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: Musashi and Kojiro

I recently finished reading Eiji Yoshikawa’s long, 1,500-page novel, Musashi, originally serialized in Japanese newspaper Asahi Shimbun between 1935 and 1939. It tells a fictionalized story of the early life of Musashi Miyamoto, the celebrated author of The Book of Five Rings who is considered by many the finest exemplar of Bushido, the warrior code of the samurai.

It was a good read, which was no surprise — the book has sold far more than 100 million copies, and its depiction of Musashi has inspired a number of screen incarnations, none more famous than Hiroshi Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy (1954-1956), starring Toshiro Mifune as Musashi. After finishing the novel I decided to give the films a rewatch and they stood up well, so I thought I’d present them here. Of course, we covered Samurai I in a Cinema of Swords article in October 2020, but here are Samurai II and III and a sort of spin-off from the following year, Sasaki Kojiro.

Samurai II: Duel at Ichijoji Temple

Rating: *****

Origin: Japan, 1955

Director: Hiroshi Inagaki

Source: Criterion DVD

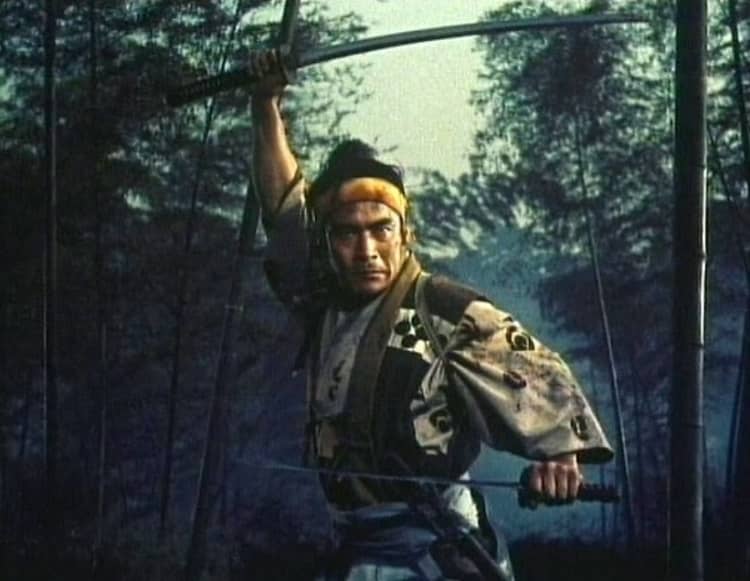

For a movie less than two hours long, there’s an awful lot going on here. As the second film in a trilogy, this one has to do the heavy lifting of supporting the central arch of the hero’s character development, as well as marching the story forward and setting up the climactic final movie, and it does all this with clarity, economy, and finesse. And that’s important, because this is the part of the story where the legendary Musashi Miyamoto, played once again by Toshiro Mifune, must evolve from an angry and arrogant bully into a humble and honorable samurai warrior.

As far as Musashi is concerned, the story is a succession of combat encounters separated by meetings with surprising mentors — a caustic old monk, an accomplished geisha, a reverent sword-polisher — who teach him to find himself by looking within. For the rest of the ever-burgeoning cast, it’s a frantic dance of deceit, adoration, conspiracy, rape, greed, ambition, calculation, and murder, in a carefully orchestrated flow of short, sharp scenes that keep the story moving so deftly you can almost ignore its frequent mind-boggling coincidences.

All the characters introduced in the first movie return to be joined by an equal number of new faces, most of whom make it to the end of this film with their plots still unresolved. The most important new character is Kojiro Sasaki (Koji Suruta), a wry and cynical young swordsman who seems to dog Musashi’s every footstep, showing up whenever there’s trouble, sometimes fomenting it, sometimes defusing it, but always with an eye toward an inevitable showdown with Musashi.

Speaking of showdowns, there’s a lot of fighting in this entry, much more than in the previous picture, and director Inagaki shows himself to be a master of the form. But of all the combats in the film, significantly only the first and last are shown from beginning to end, because they bookend Musashi’s character arc; all other fights are only partially depicted, mere links in the chain of the story’s progress.

The movie opens on the first duel, in which Musashi has been challenged by Baiken, a master of the kusari gama (chain and sickle). Musashi, facing an unfamiliar weapon, is unsure of himself, gets caught by the chain, and wins only through audacity and desperation. An aging monk who witnesses the duel tells him disapprovingly that though victorious, he is no samurai, as he didn’t win by art or skill, only sheer force. “You are decidedly too strong,” he says.

Only as events unfold does Musashi begin to glimpse what the monk means. He gets into a protracted squabble with the many swordsmen of the Yoshioka fencing school, whom he repeatedly defeats while demanding a match with the young samurai who has inherited the school’s mastery — a duel which is always denied him, because the Yoshioka students secretly fear their master is no match for Musashi. They keep trying to kill him in failed or mistaken ambushes, and the wrong people die. Meanwhile all the secondary characters pursue their agendas of love and avarice in and around this feud, and hostilities sharpen and harden.

Finally, a duel between Musashi and Seijuro Yoshioka (Akihito Hirata) is set for dawn at Ichijoji Temple — but once again the master is diverted, and some eighty of his students set an ambush for Musashi. Forewarned by Akemi, one of the three women pining for his affections, Musashi defies the ambushers and then battles the lot of them in a magnificent fighting retreat, carefully choosing his terrain so they can come at him only a few at a time. After dropping two dozen adversaries, Musashi eventually breaks away into the forest, nearly exhausted, only to be confronted by Seijuro at last. Musashi can barely contain his rage: after taking the measure of his opponent, he defeats Seijuro in a single pass, but then refrains from killing him as all his recent life lessons combine to restrain his hand. Which leaves all the elements set up to perfection for resolution in the final film.

Samurai III: Duel at Ganryu Island

Rating: ***** (Essential)

Origin: Japan, 1956

Director: Hiroshi Inagaki

Source: Criterion Blu-Ray

This is the final film in Inagaki’s epic trilogy adapting Eiji Yoshikawa’s biographical novel of the early life of Musashi Miyamoto, the exemplar of Bushido. It leads up to the inevitable duel between Musashi (Toshiro Mifune) and his arch-rival Kojiro Sasaki (Koji Tsuruta), introduced in the previous movie. But more than that, the purpose of this film is to draw a contrast between the vainglorious Kojiro and the increasingly humble and thoughtful Musashi.

It does this from the very beginning, the first scene showing Kojiro at a waterfall, a location of great natural beauty; but this beauty is ignored by the samurai, who sees a passing swallow as nothing more than a challenge to his sword-skill, bringing it down with a single lightning stroke. Meanwhile, Musashi, when challenged by a boastful spear-wielding monk, declines to draw his own sword, and instead neutralizes his opponent by grabbing the end of his spear and using his own strength against him.

This sort of thing continues: Kojiro defeats his adversaries in flashy duels, burnishing his reputation, while Musashi avoids a brawl with a gang of thugs in a famous scene where he awes them with his skill by using chopsticks to grab flies on the wing. Though Kojiro has never lost a duel, neither has Musashi; realizing that only Musashi is a match for him, Kojiro challenges him, but Musashi temporizes, putting him off for a year “to train further.”

Musashi’s idea of further training is to return to the simple life of the soil. He becomes a farmer at a village where the peasants, repeatedly raided by bandits, are giving up in despair. But the complications of his old life pursue him into the countryside: Otsu (Kaoru Yachigusa), who’s loved him since he was a youth, shows up at the village, as does the bandits’ moll Akemi, who also pines for Musashi. Jealous of Otsu, she calls the bandits down on the village, and Musashi must fight to defend the peasants.

At last, the reckoning with Kojiro can be put off no longer. Inagaki’s depictions of the fights in this film are impeccable, but the final duel at dawn on the beach at Ganryu Island is a thing of beauty, a ballet of light, water, and weaponry, a few simple elements the director combines into a scene both elegant and unforgettable, exemplifying all that’s gone before. I think I’ll go watch it again.

Sasaki Kojiro, Parts 1 & 2

Rating: ***

Origin: Japan, 1957

Director: Kiyoshi Saeki

Source: Samurai DVD

Considering how many stories and screenplays there are about the fencer Sasaki Kojiro, the great opponent of the legendary Musashi Miyamoto, you’d think there must be plenty of biographical material about him, but on the contrary: historians aren’t even sure he really existed. However, thanks to his appearance in Eiji Yoshikawa’s epic mega-novel Musashi (1939) and its many subsequent film adaptations, Kojiro is as well known in Japan for appearing in Musashi’s story as Doc Holliday is in the West for appearing in Wyatt Earp’s saga.

This three-hour tale, released in two parts in quick succession to Japanese theaters in 1957, is based not on Yoshikawa’s more famous work, but on Genzo Murakami’s 1949 novel about the life of Kojiro, featuring only occasional appearances by Musashi. It’s a tragedy from the start, if only because Japanese audiences know how it will end, as well as you know that a movie about the Titanic has to conclude with the ship going down.

In this version of the story, Kojiro is a sensitive and artistic young samurai with an elegant sword style, a ronin of no family who aspires to fame as a fencer so he can marry Tone (Shinobu Chihara), his lady love of higher rank. But Kojiro’s attempts to make a name for himself by dueling the masters of well-known fencing schools is initially a frustrating failure, as nobody famous wants to cross swords with a nobody. This is partly due to Kojiro’s appearance, as he presents himself as a romantic youth who wears eccentric clothing and won’t shave his forelock, which in a samurai context seems effeminate; indeed, he’s even mistaken once for a male prostitute.

But Kojiro persists in his ambitions without compromising his appearance, and along the way he makes both enemies and friends. The time is the early 1600s, at the beginning of the Tokugawa Shogunate, and Japan is still riven by political intrigue; Kojiro tries to avoid becoming a pawn of the rival factions but can’t entirely escape clan politics. Fortunately, he is guided by his loyal friend Shimabei, a ninja spy (with a nagging ninja spy wife!) who masquerades as a street puppeteer, and by Okuni, the nation’s most famous dancer, who moves freely through the dangerous world of the clan lords.

Kojiro’s heart is lifted by song and his soul is inspired by dance, and it’s by watching Oman, a dancer who falls in love with him, that Kojiro develops the “turning swallow” sword style with which he finally makes a name for himself. After that he has only one more ambition: to defeat his rival, Musashi Miyamoto.

This is a big-budget widescreen epic from Toei Studios with high end production values and strong performances from all concerned. Former kabuki actor Chiyonosuke Azuma cuts an appealing figure as Kojiro, and Chiezo Kataoko is a formidable screen presence as Musashi: having played the role a half-dozen times before in previous films, he steals every scene in which he appears. Watch this for a different take on the same characters portrayed in Inagaki’s Samurai trilogy with Toshiro Mifune.

Where can I watch these movies? I’m glad you asked! Many movies and TV shows are available on disk in DVD or Blu-ray formats, but nowadays we live in a new world of streaming services, more every month it seems. However, it can be hard to find what content will stream in your location, since the market is evolving and global services are a patchwork quilt of rights and availability. I recommend JustWatch.com, a search engine that scans streaming services to find the title of your choice. Give it a try. And if you have a better alternative, let us know.

Previous installments in the Cinema of Swords include:

Warmongers

Fables and Fairy Tales

Goofballs in Harem Pants, Part 2

Timey-Wimey Swordy-Boardy

Boy-Toys of Troy

Piracy – Two Wrecks and a Prize Ship

Postwar in the Greenwood

The Barbarian Boom, Part 4

Blood-Red and Blind: The Crimson Bat

Updating the Classics

Sink Me! Scarlet Pimpernels!

The Barbarian Boom, Part 5

Alexandre/Alexander

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle, with the fifth volume, Between Two Kings, available now from Pegasus Books in the US and UK. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net.

Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he’s writing Dungeons & Dragons scenarios for Larian Studios’ Baldur’s Gate 3.

Nice write up, Lawrence!

While I agree with your praising of Inagaki’s shot compositions and use of colors, (the Samurai Trilogy are really beautiful films to watch), I personally could only stand to watch them twice, each. I read the book ages ago, and grew to hate the characters in it with their various grating characteristics and flaws. Watching the films, I saw that Inagaki fairly faithfully followed the book in his movies, which sadly made me not like the movies. It’s a running joke with one of my friends whenever we mention the book or the movies how I start ranting about Otsu, Matashichi, and Granny…

However, I do much prefer the quintology of films made from the book starring Yorozuya Kinnosuke as Musashi, and when I finally steeled myself to watch the 2003 Taiga drama adaptation of the book, how much I loved that version. Although to be fair, the Taiga did make some massive changes to the characters of Otsu, Matashichi, Granny, and the others to make them more well-rounded and likable.

I totally agree with you on the Sasaki Kojiro films. Both very good films! Thanks for a good article on some fairly important Samurai films.

Another Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords? Thank you very much!

While I own copies of the Samurai Trilogy, I have never heard of those two films about Kojiro. Fascinating. Thanks again for pointing me at films that I never knew existed.