Six Thousand Years of Galactic Empires, Space Pirates, and Fuzzies: H. Beam Piper’s Rich Future History

|

|

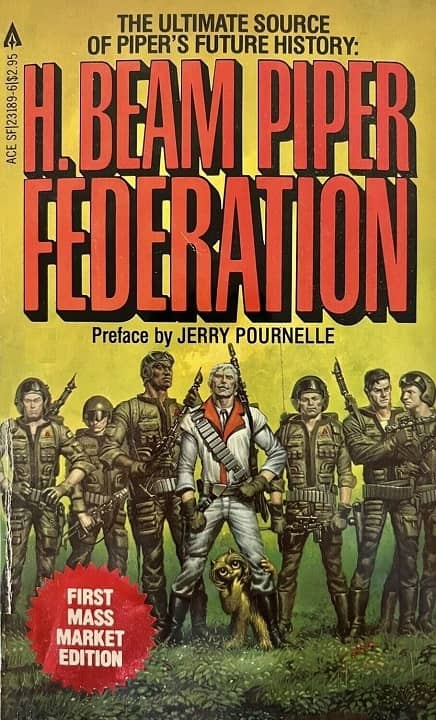

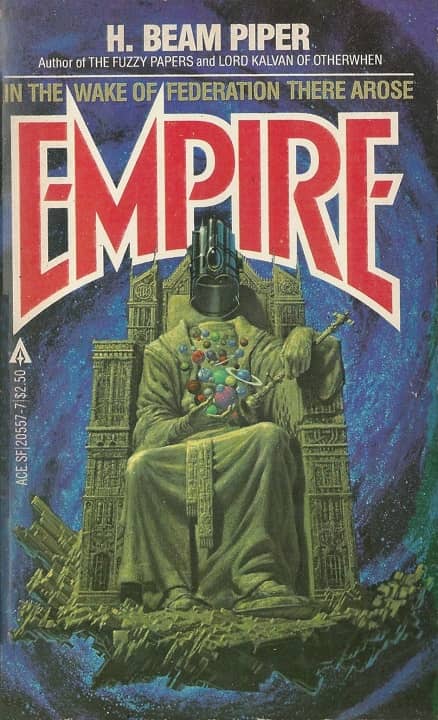

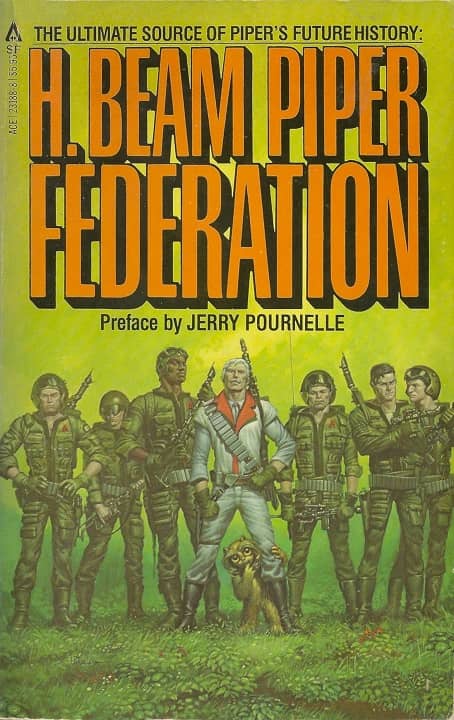

H. Beam Piper’s Federation and Empire (Ace Books, February 1982 and May 1981). Covers by Michael Whelan

H. Beam Piper is an enduring favorite of mine. I love his SF adventure tales, including The Fuzzy Papers and the stories in his Paratime sequence. But I haven’t really dipped into his more ambitious work, the Future History that tied together most of his longer stories. The Zarthani website dedicated to Piper’s work summarizes it succinctly:

Piper’s Terro-human Future History is a future-historical science-fiction series which imagines the expansion of the human race from its origins on Earth (Terra) out into the galaxy. Consisting of the novels of Piper’s famous Fuzzy trilogy — Little Fuzzy (1962), Fuzzy Sapiens (…1964) — and Fuzzies and Other People (published posthumously in 1984), Piper’s novels Uller Uprising (1952), Four-Day Planet (1961), Junkyard Planet (1963) — also known as The Cosmic Computer, and Space Viking (1962), and eight Piper stories originally published in pulp science-fiction magazines between 1957 and 1962 (originally reissued, along with an additional, previously-unpublished story, in the Piper collections Federation and Empire edited by John F. Carr, and more recently in Carr’s The Rise of the Terran Federation), the Terro-human Future History spans over thirty millennia of future history.

Piper’s Future History has been much celebrated and discussed since his death, and we’re long overdue for a closer look here. Grab your beverage of choice, settle back in your favorite chair, and let’s dive in.

|

|

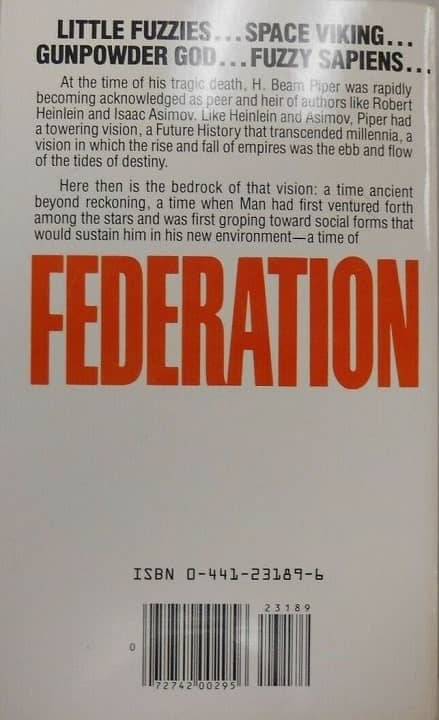

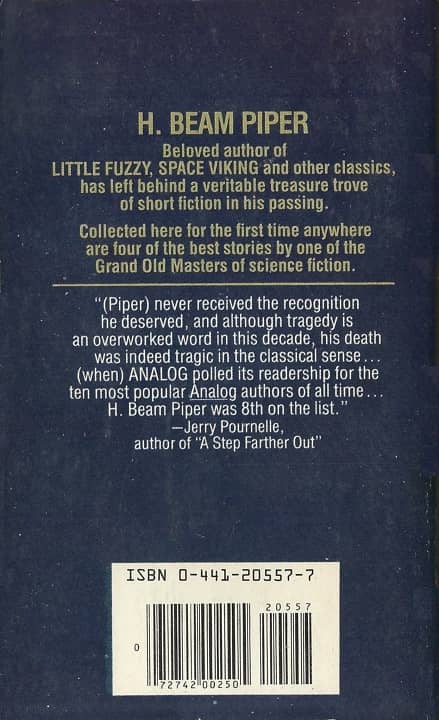

Back covers for Federation and Empire

Piper’s first short story “Time and Again” appeared in the April 1947 issue of John W. Campbell’s Astounding. He produced short fiction almost exclusively for the first 14 years of his career, until G. P. Putnam’s Sons bought his novel Four-Day Planet in 1961. He followed that with a quick succession of popular novels, including Little Fuzzy (1962), The Cosmic Computer (1963), and Space Viking (1963).

In 1964 Piper’s agent died before informing him of several sales. Deeply in debt and with his career apparently in decline, Piper died by suicide in November 1964, at the age of 60. The exact date is unknown; his body was discovered on November 8. The note he left ended with the words:

I don’t like to leave messes when I go away, but if I could have cleaned up any of this mess, I wouldn’t be going away.

— H. Beam Piper

The true reasons for his suicide of course remain unknown, though there’s been no shortage of fannish theories over the decades. Jerry Pournelle, his editor at Ace, couldn’t believe that he’d died by his own hand, and contacted the police in Williamsport, convinced that he had been “murdered by someone clever,” but no, his suicide note was authentic. Pournelle later stated publicly that Piper had been impoverished by a bitter divorce; George H. Scithers, who was fairly close to Piper, claimed that he aimed to spite his ex-wife, and by killing himself he voided his life insurance policy and prevented her from collecting any benefits.

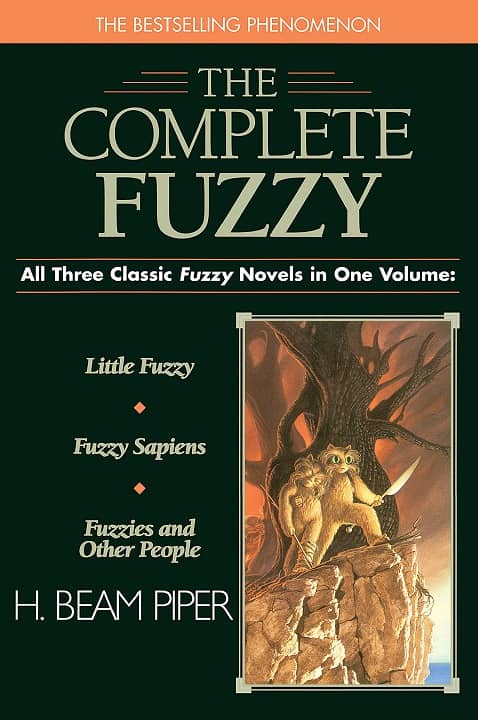

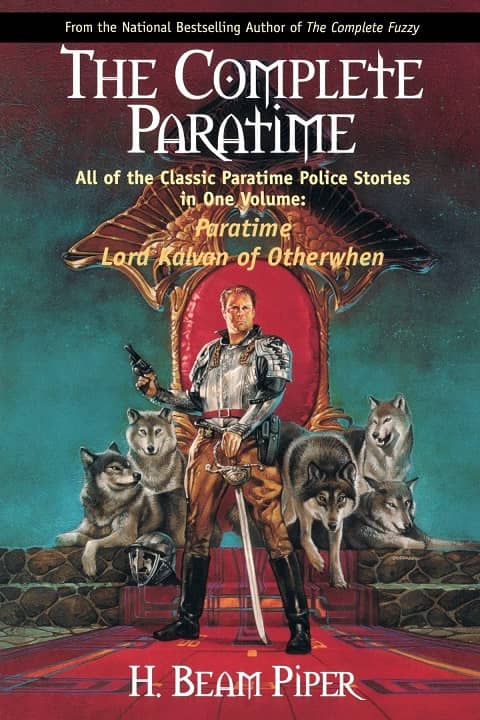

Piper’s back catalog was eventually snapped up by Pournelle and Tom Doherty at Ace Books, who packaged it up for paperback publication. The Fuzzy novels formed a compact trilogy and the Paratime stories fit neatly into two volumes (Paratime and Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen), but the rest of his work, which shared a vast galactic setting but was spread out over thousands of years, not so much.

|

|

Trade paperback first edition of Federation (Ace Books, February 1981)

Doherty and Pournelle were both industry savvy, and they knew what the the public wanted. Piper’s remaining catalog in many ways resembled the sprawling future histories of two of the most popular SF properties on the market, Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy and Robert A. Heinlein’s The Past Through Tomorrow. All three authors wrote for (and were influenced by) John W. Campbell.

Doherty and Pournelle knew the best way to present this material was as a unified future history in the same mold — even though the stories themselves spanned thousands of years. Over the next seven years they packaged the books up in attractive new editions, virtually all with covers by Michael Whelan:

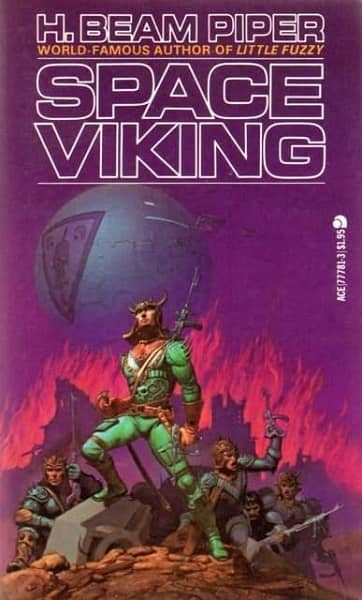

Space Viking (1977) — The aftermath of the Interstellar Wars that destroy the Terran Federation and give rise to the age of Space Piracy (after A.E. 1399)

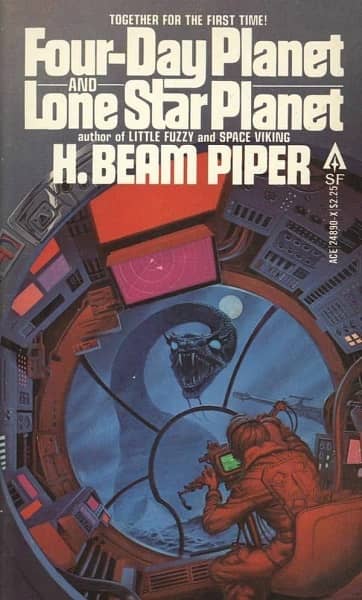

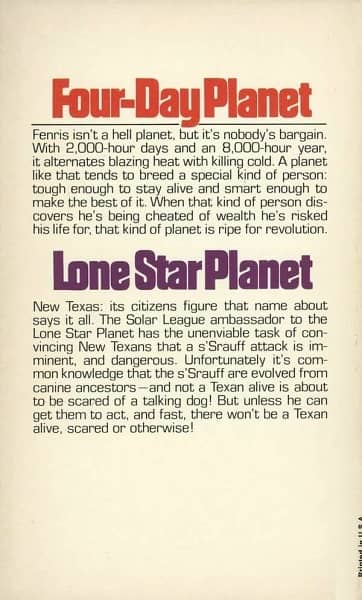

Four-Day Planet (1979) — A revolution on the hellworld Fenris, which has 2,000-hour days

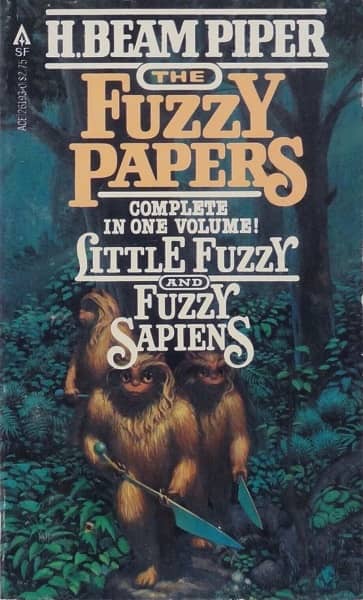

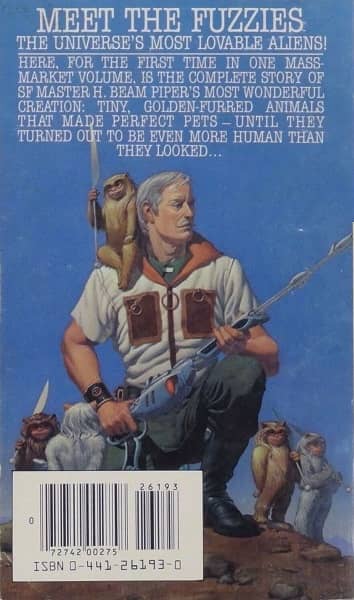

Little Fuzzy and Fuzzy Sapiens (gathered as The Fuzzy Papers in 1980) — Jack Holloway helps the native species on Zarathrustra resist colonization by a mining corporation in A.E. 629

Federation, edited by John F. Carr (1981) — Five stories set during the Terran Federation, A.E. 39 – 1399

Empire, edited by John F. Carr (1981) — Four long stories set after King Steven IV becomes First Galactic Emperor in A.E. 1848

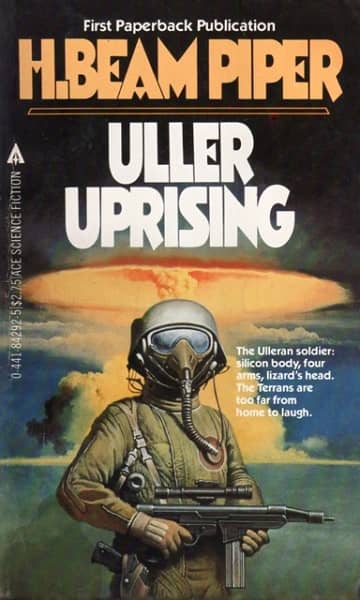

Uller Uprising (1983) — The revolt against the Federation in A.E. 377

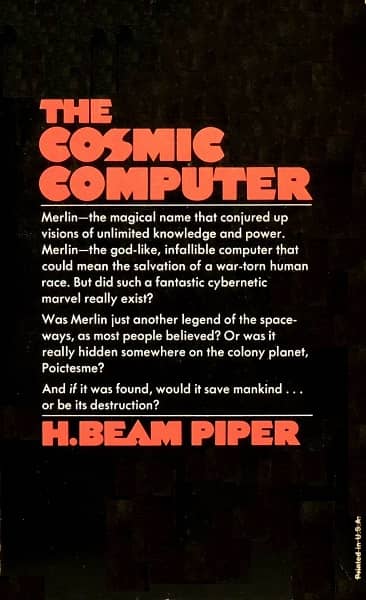

The Cosmic Computer (1983) — The discovery of Merlin, the great Federation battle computer on the planet Poictesme in A.E. 849

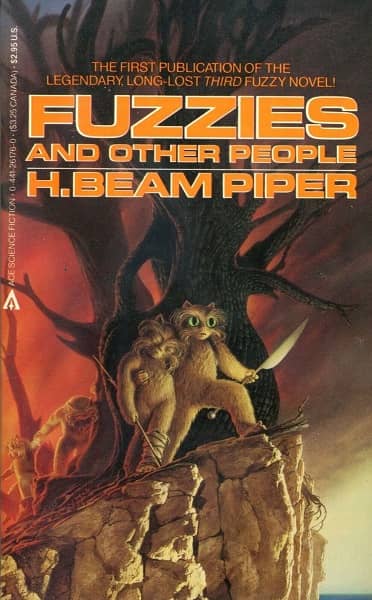

Fuzzies and Other People (1984) — The long-rumored final Fuzzy novel was found amongst Piper’s papers and published posthumously

Ace also published one additional collection, The Worlds of H. Beam Piper, in 1983, gathering Piper’s non-Future History work.

As Jerry Pournelle notes on the back cover of Empire,

[Piper] never received the recognition he deserved, and although tragedy is an overworked word in this decade, his death was indeed tragic in the classical sense…. (when) Analog polled its readership for the ten most popular Analog authors of all time… H. Beam Piper was 8th on the list.

Piper ceased writing in 1964, but like Robert E. Howard, H.P. Lovecraft and a small handful of other genre writers before, his fame grew steadily after his death. Today, nearly six decades after he last sat down at a typewriter, Piper’s most popular works — including all three Fuzzy novels and his complete Paratime series — are still in print, still widely discussed, and still winning fans.

|

|

|

|

|

|

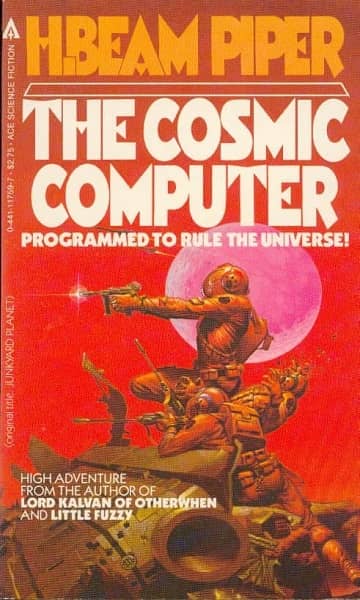

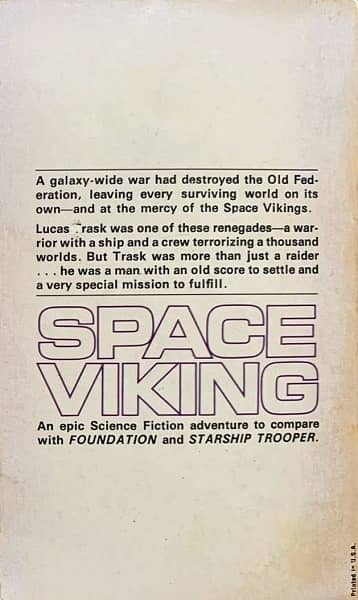

Other books in Piper’s Future History: Space Viking, the omnibus Four-Day Planet and Lone Star Planet, and

The Cosmic Computer (Ace Books, January 1977, April 1979, and November 1983). Covers by Michael Whelan

Piper’s Future History begins in the year 1942, the birth of the Atomic Age and the first fission reactor, which eventually becomes known as 1 A.E. (Atomic Era). The Earth is nearly destroyed by nuclear war in 1973; the discovery of antigravity (“contragravity”) in 2034 lays the groundwork for the first Space Age and the emergence of the Terran Federation.

Piper’s 1957 novella “The Edge of the Knife,” a contemporary story set in the early 70s before the nuclear war, centers on history professor Edward Chalmers, who has visions of the future and ends up accidently teaching his students events that haven’t happened yet. It links multiple important events from Piper’s future history and is a useful story to start with; it is collected in Empire.

The Terran Federation in Piper’s stories suffers the same fate as Asimov’s Foundation, Poul Anderson’s Polesotechnic League, George Lucas’ Galactic Republic, and countless other mid-Century space opera civilizations modeled on Edward Gibbon’s The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire. Namely, it collapses, and gives rise to a galaxy-spanning Empire.

Science Fiction as a genre was smitten with the romantic ideal of the inevitable collapse of civilization last century. I dunno why, other than it arguably did yield a lot of entertaining stories with an admittedly operatic sweep and scale. Maybe that’s all the reason you need.

In any event, Piper’s Terran Federation predictably collapses in the System States War; afterward follows the Interstellar Wars (The Cosmic Computer has some of the details), and a lengthy period of barbarism, warfare between local systems and — you know it! — space piracy. Piper set Space Viking, the tale of the feudal Swords Worlds and their armed forays into the poorly defended worlds of the Old Federation, in this colorful period.

The interstellar dark ages end when King Steven IV declares himself First Galactic Emperor in A.E. 1848, and sets about re-unifying the far-flung outposts of mankind. A series of Imperial dynasties (at least five) rise and fall over the next four millennia.

Piper’s star-spanning civilization is both imaginative and familiar, especially to modern readers. To me it fits the comfortable mold of a lot of 1950s-60s era space opera, drawing liberally from E.E. “Doc” Smith and Edward Gibbons. If you’re a player of the Traveller role playing game it may seem particulary familiar; Piper — along with Poul Anderson and E.C. Tubb — was strongly influential on the game. It’s one of the reasons I called Traveller a Classic Science Fiction simulator.

|

|

|

|

|

|

More Future History volumes: Uller Uprising, The Fuzzy Papers, and Fuzzies and Other People

(Ace Books, June 1983, September 1980, and August 1984). Covers by Gino D’Achille and Michael Whelan

Federation includes a forward by Jerry Pournelle, an introduction by editor John F. Carr, the long novella “When in the Course—”, and four other stories. Here’s the complete Table of Contents:

Piper’s Foundation by Jerry Pournelle

Introduction by John F. Carr

“Omnilingual” (Astounding Science Fiction, February 1957)

“Naudsonce” (Analog Science Fact & Science Fiction, January 1962)

“Oomphel in the Sky” (Analog Science Fact & Fiction, November 1960)

“Graveyard of Dreams” (Galaxy Science Fiction, February 1958)

“When in the Course—” (1981)

The novella “When in the Course—” was found among Piper’s papers and appeared here for the first time. It is very similar to Piper’s earlier Paratime story “Gunpowder God.” Editor John Carr notes “except for the last half, this is the story of Lord Kalvan of Otherwhen — except he’s not in it and these Federation people are!”

Empire has a new intro by Carr, a very handy Chronology of the entire Terro-Human Future History, two novellas, “The Edge of the Knife” and “A Slave Is a Slave,” and three other stories, including a collaboration with John J. McGuire. Here’s the complete TOC.

Terro-Human Future History Chronology by John F. Carr

Introduction by John F. Carr

“The Edge of the Knife” (Amazing Stories, May 1957)

“A Slave Is a Slave” (Analog Science Fact & Science Fiction, April 1962)

“Ministry of Disturbance” (Astounding Science Fiction, December 1958)

“The Return” by John J. McGuire and H. Beam Piper (Astounding Science Fiction, January 1954)

“The Keeper” (Venture Science Fiction Magazine, July 1957)

Several readers have used the events of Piper’s 1951 story “Genesis” (included in The Worlds of H. Beam Piper) to theorize that Piper’s entire Future History is in fact an alternate world in the Paratime universe. It’s a neat idea, but Piper never wrote anything else to support it.

Federation was published in February 1981. It is 314 pages, priced at $5.95 in trade paperback and $2.95 in mass market. Empire was published in May 1981. It is 250 pages, priced at $2.50 in paperback. Both were published by Ace and edited by John F. Carr; the covers are by Michael Whelan. Both books have been out of print since 1986, and there are no digital editions.

|

|

H. Beam Piper’s The Complete Fuzzy and The Complete Paratime

(Ace Books, December 1998 and March 2001). Covers by Michael Whelan and Dave Dorman

Our previous coverage of H. Beam Piper includes:

Lord Kalvan Of Otherwhen: Piper’s Connecticut Yankee Tale by Sara Light-Waller (June 2021)

Into The Quantum with H. Beam Piper by Sara Light-Waller (April 2021)

Vintage Treasures: H. Beam Piper’s Paratime Tales (March 2021)

Space Viking by H. Beam Piper by Fletcher Vredenburgh (March 2017)

The Omnibus Volumes of H. Beam Piper (April 2015)

Vintage Treasures: The Fuzzy Papers by H. Beam Piper (February 2013)

There’s plenty of great information about Piper at The H. Beam Piper Memorial Site, founded by Dennis Frank and John F. Carr in 2007.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Definitely one of my top ten Science fiction authors. I have read his novels and short stories many times. Great material for out Traveller campaigns

David,

I’m not sure what it is about Piper’s Future History that makes me yearn to grab some dice and roll up a Traveller character. Certainly his influence on the game is obvious.

Tell me more about your campaign — is it set in the Terro-human Future History?

We stick to third imperium. We are traditionaList that way, but H.Beam Piper haunts our games

It’s a shocking gap, I know, but I’ve never read Piper. It’s never too late, though, and summer is coming!

Love to hear what you think, Thomas. I think the Fuzzy books would be classified as YA today — certainly they were among the first real SF books I gave to my young sons, and they both loved them!

Federation is on the way. You gotta love Ebay…unless you’re married to one of us degenerates…

I have this but haven’t got around to reading it.

Matthew — let us know what you think when you do. It was my interest in reading both FEDERATION and EMPIRE that triggered me to write this article. I’m very interesting in hearing what folks think of both books.

Okay, I thought it was a decent collection but not a brilliant one. I decided that my copy will go to the used bookstore for the simple reason that though I certainly enjoyed it I don’t think that I’d want to read it again.

I found Piper a very reliably entertaining writer. His politics can grate at times, but, well, so can anyone’s, really. (Though “Ullr Uprising” has the all too common naive colonialism that was popular then: as I wrote it’s “a retelling of the Sepoy Mutiny. And I must say I found much of it distasteful, with the deck-stacking portrayal of the “good aliens” vs. the “bad aliens”, and with the cheerful use of terms like “geek” by the “good guys”. (It’s OK, see, because the bad aliens call humans “suddabits”, which is apparently the best their vocal equipment can do with “son of a bitch”.)

I use the title “Ullr” because that was the title in the Space Science Fiction magazine serialization, which was NOT the original publication — it was originally part of the only finished science fiction Twayne Triplet.) “Ullr Uprising” also introduces some character names that other authors later reused (consciously or not): Retief, Lafayette O’Leary, and Falkenberg.

Reliably entertaining is a great way to describe Piper’s work. I’ve read most of his stories, including both of these collections and he never disappoints.

Great post, Mr. O’Neill.