Still Not Telling Us: “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” by James Tiptree, Jr.

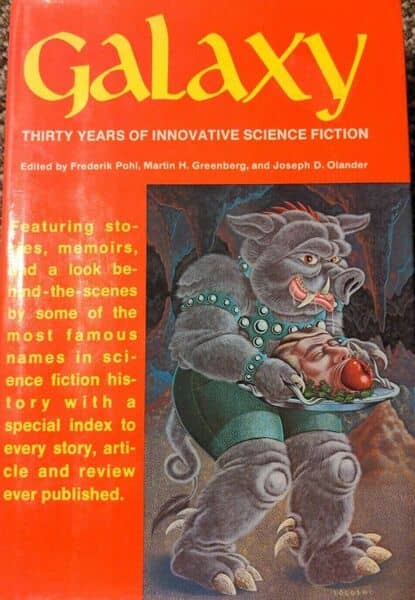

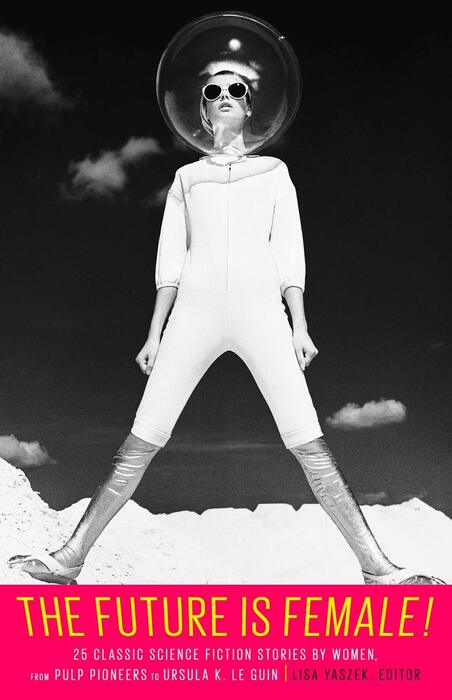

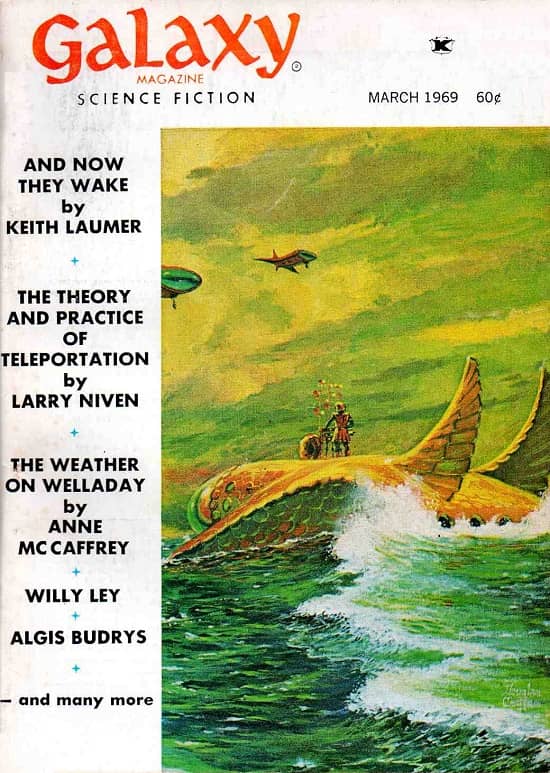

Galaxy, March 1969, containing “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain,” by James Tiptree, Jr. Cover by Chaffee

“. . . Take ‘The Last Flight of Dr. Ain.’ That whole damn story is told backward. . .. It’s a perfect example of Tiptree’s basic narrative instinct. Start from the end and preferably 5,000 feet underground on a dark day and then DON’T TELL THEM.”

This is James Tiptree, Jr., on his story “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain.” Or, this is Alice Sheldon, referring to “Tiptree” in the third person — and, still, NOT TELLING US.

“Tiptree”/Sheldon was a little dismissive of “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” at times. I disagree. It was certainly the first of her stories to gain wide notice (and a Nebula nomination.) And it’s the earliest of her publications to really light me up. Thus I’d like to take a very close look at it here, in my latest piece trying to figure out how stories, particularly good stories, really work. (I note with some amusement that this essay is roughly the same length as the original story. I also add that of necessity I have “spoiled” the story, but I add that this story in particular is unspoilable, partly because it demands and rewards rereading. That said, if you haven’t read the story and you can find a copy, do go ahead and read it first!)

[Click images to embiggen.]

James Tiptree, Jr., was of course the pseudonym chosen by the woman born Alice Hastings Bradley, daughter of the noted writer Mary Hastings Bradley, when she began to write Science Fiction in the mid ’60s. (Tiptree was a brand of marmalade — still available!) She was used to identity shifts already — her first writing (art criticism as well as painting) was done as Alice Bradley Davey, her first married name. She spent the war working in intelligence, and shortly after the war sold a piece to The New Yorker about life in occupied Germany, “The Lucky Ones,” bylined Alice Bradley, though by this time she was married to Huntington Sheldon. (It is often called a “story” but it reads to me as memoir.) She went by Alice Sheldon for the rest of her life.

She gained a Ph.D. in Psychology by 1967, around when she began writing and selling science fiction. She suffered from depression, and her husband’s health also declined precipitously, and in 1986 she killed her husband and herself in what was probably (though not definitively) a mutual suicide pact. This ending, in retrospect, seems almost signaled by a profound preoccupation with death — with suicide, even, and suicide as a moral act — that runs throughout her published work.

Tiptree’s first SF sale was “Birth of a Salesman,” to John W. Campbell, Jr., at Analog, and apparently her second accepted story was to Harry Harrison at Fantastic (or so Harrison claimed.) But of her first nine published stories, two went to Campbell, one to Harrison, and six — the best six — to Frederik Pohl, editor of Galaxy and If.

I don’t know that it’s been acknowledged often how significant Pohl was early in her career. By 1970 she was selling to F&SF and to anthologies and it was clear that everyone wanted Tiptree stories… but Pohl, in my opinion easily the key magazine editor of the second half of the 1960s, was central to establishing the Tiptree name.

|

|

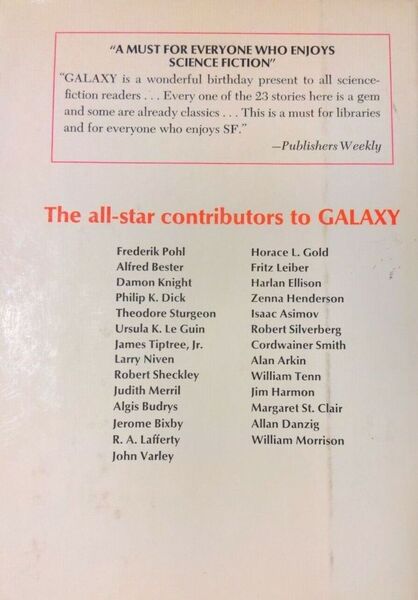

Galaxy: Thirty Years of Innovative Science Fiction, edited by Martin H. Greenberg,

Joseph D. Olander, & Frederik Pohl (Playboy Press, 1980). Cover by Tommy Soloski

And of all the Tiptree stories Pohl bought, “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” is the greatest. It appeared in the March 1969 issue of Galaxy. (Pohl presumably agreed with my assessment – he chose it for the anthology Galaxy: Thirty Years of Innovative Science Fiction.)

I spoke of death, and indeed of suicide, as essential themes in Tiptree’s fiction. (I hesitate, mind you, to directly link that theme to Tiptree’s own final action.) And this story is absolutely a story of suicide — of murder-suicide, mass murder/suicide. And treated as a moral action. But — let’s go to the story itself.

Dr. Ain is a scientist, and the story is told as reports of his final trip, first to a conference in Moscow, then back home to the US. Ain is clearly sick, and, we soon realize, there is something going around: lots of people are sick. And why is the narrator — or his group — tracking Dr. Ain’s movements? (In retrospect, it becomes clear.) One clue: he seems to be accompanied by a mysterious woman, whom they are having a hard time finding. She is sick too, though:

The woman was weaker now. She coughed, picking weakly at the scabs on her face hidden by her long hair. Her hair, Ain saw, that great mane which had been so splendid, was drabbed and thinning now.

Ain’s flight continues, switching planes from time to time. A walk on the beach in Iceland:

A flock of wheatears foraged by the path. Next month they would be in North Africa, Ain thought. Two thousand miles of tiny wing-beats. He threw them some crumbs from a packet in his pocket.

There is a glorious passage describing Ain’s first meeting with the woman (“the day his life began”):

The shocking girl-flesh, creamy, pink-tipped, coming toward him among the golden bracken… And then he was staring at the fall of that outrageous hair down her narrow back, watching it dance around her heart-shaped buttocks… The lake was utterly still, dusty silver under the misty sky, and she made no more than a muskrat’s ripple to rock the floating golden leaves… For a time, he believed he had seen an oread.

The last leg takes Ain from Glasgow to Moscow, and he meets a former teacher of his, who speaks of Ain’s abilities and the people tracking him… a brilliant man, eccentric as great scientists often are, always did feed the birds, but would never do a harmful deed. And more description of Ain’s relationship with the woman,

The miracle, the wealth of her body, her inexhaustibility… His dreams were of her sweet springs and shadowed places and white rounded glory in the moonlight, finding always more, always new dimensions of his joy… The danger of her frailty was far off then in the rush of birdsong and the springing leverets of the meadow.

The Moscow conference doesn’t go so well — Ain is seriously ill, and drops hints about biological warfare, and something missing from his lab, and makes strange comments about the course of evolution. And then he mentions his efforts to mutate a virus — transmissible by any warm-blooded creature — no primate survives beyond 22 days… Ain heads home, and is soon in custody, very ill, and raving … but so too are his captors ill. Some more words about the woman:

Oh beautiful, you won’t die. I won’t let you die. I tell you girl, it’s over… Lustrous eyes, look at me, let me see you now alive! Great queen, my sweet body, my girl, have I saved you?

Soon Ain is dead, raving about bears in his last moments: “By any chance were you saving them, girl?”

|

|

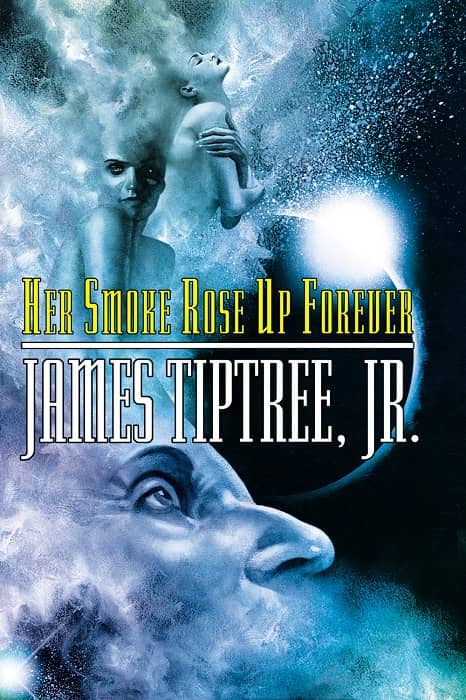

Her Smoke Rose Up Forever by James Tiptree, Jr. (Tachyon Publications, 2004). Cover by John Picacio

Okay — obviously, this is a story that came to mind during the pandemic. A highly infectious disease, spread by traveling? That’s an eerie thing to read about with our Covid consciousness. But what’s going on is something more profound. It’s clear by the end that Dr. Ain has engineered a disease with the goal of eliminating humankind, and his last flight is aimed at spreading it as widely as possible. (And was probably unnecessary, but let that be.)

This is a dark idea, and not a totally unfamiliar one, though Tiptree’s story is one of the first I can remember centering the idea so starkly. She returned to very similar ideas in her own work, especially in two stories both apparently written as by “Raccoona Sheldon”: one brilliant (and with a different angle), “The Screwfly Solution”; the other a clumsy and vulgar reworking at excessive length of the conceit of “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain”, a story only published posthumously under the Tiptree byline, “The Earth Doth Like a Snake Renew.”

Other writers to take on a similar idea include Isaac Asimov in his 1976 story “The Winnowing,” and Albert E. Cowdrey in “A Balance of Terrors” (2004) — this last a piece that I believe was written explicitly as a riff on “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain.” And, of course, a famous movie treats a similar idea: Terry Gilliam’s 12 Monkeys (1995).

The other secret in the story is, of course, the identity of the woman in Dr. Ain’s life. The woman is of course the Earth, and every gorgeous description of her is a metaphor for natural beauty — and, of course, for ecological decay.

I think the descriptions of the woman — and hence of Earth — are some of the most beautiful prose Tiptree ever wrote. Tiptree was always a strong writer, and certainly capable of striking prose throughout her oeuvre, but much of her effects were through rhythm, through drive. Here she gives in to lushness. (While never abandoning drive — “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” is a headlong dash to destruction as well as a sometimes extravagant paean to nature.)

This makes this a story to reread. On first reading it took me most of the story before things clicked into place. It is on a second reading (and more — I have read this fairly short story at least a dozen times over the years) that one appreciates the subtle reveals, the way the descriptions of the woman echo the state of the polluted Earth, and also celebrate her beauty.

The rest of the plot is elegant too — Ain feeding the birds (warm-blooded, we are reminded, so good vectors) — the various other people encountered in different states of illness — the throat spray Ain is using — Ain’s research, his morality. I called the story “fractal” once, which isn’t quite right, but I was trying to get at the way that on rereading the entire arc of the story seems implicit in every scene.

The message is stark and unforgiving. Dr. Ain commits suicide to save his lover. A noble act! (More sentimentally, in “The Only Neat Thing to Do,” Tiptree’s protagonist sacrifices herself to save both an alien race and future humans.) But in so doing he murders every human. And this too he believes is the higher moral act.

At one point Tiptree suggests that perhaps the Earth has more agency in this result than we might think, and there is even a hint that maybe she engineered the end of the dinosaurs as well. (Remember that in 1969 one leading theory as to the cause of the extinction of the dinosaurs was a burst of volcanic activity.) The story is wholly about death, extinction — and death and extinction leading to renewal. But a new renewal — no renewal for humanity.

And this theme is truly fundamental to Tiptree. Very often, too, death is linked to sex. This is often explicit — horrifyingly so in “The Screwfly Solution”, scarily so in “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side”, alien in “Love is the Plan, the Plan is Death” and “The Only Neat Thing to Do” … this is not so obvious in “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” but certainly Ain’s obsession with the Earth is portrayed in sexual terms.

In the end we are left, I think, feeling awe, fear, and guilt. It’s a late ’60s story in many ways, but a story that remains relevant, remains exciting, and rewards endless rereads. Indeed, I say it’s a late ‘60s story – reflecting its time of composition, and its ecological theme. But like all great stories, it renews itself, as it were – not only do its concerns remain important (certainly ecological issues never cease to matter, and the idea of a worldwide pandemic took on only too much relevance to us in 2020) – but its human core, Tiptree’s obsession with death, with sex, with biological determinism, with the interconnectedness of humans, other animals (other worlds!) is utterly compelling.

|

|

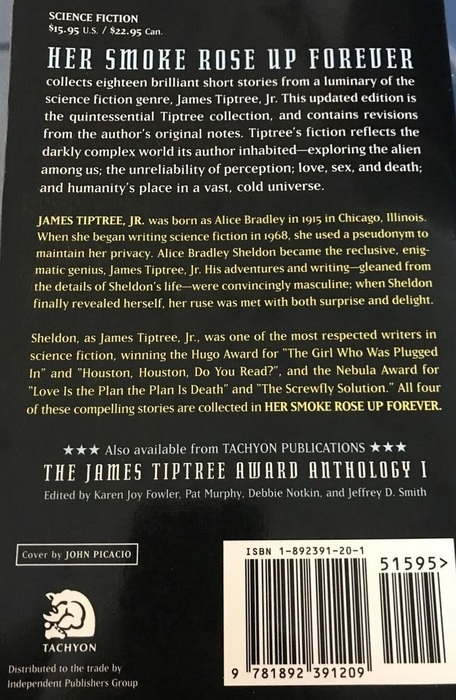

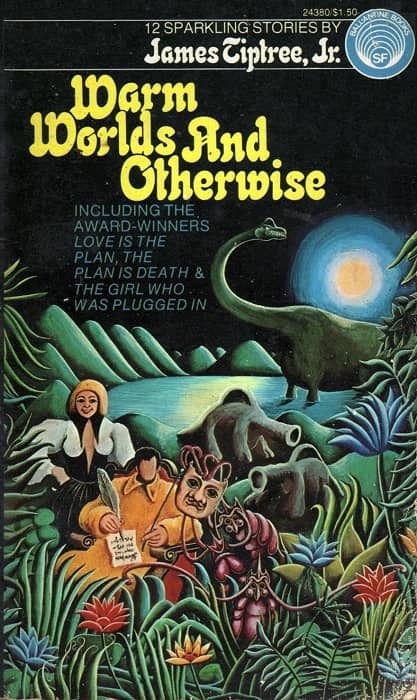

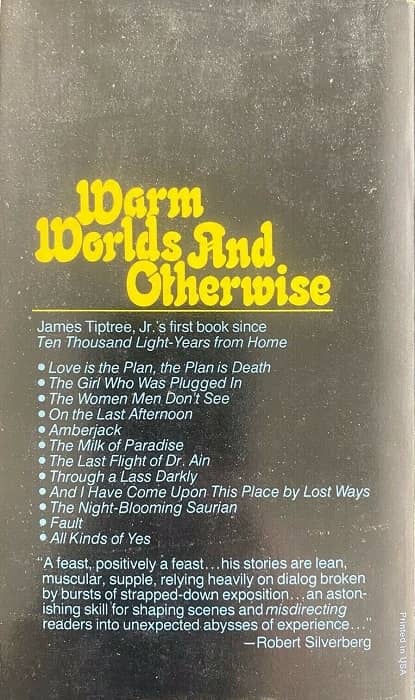

Warm Worlds and Otherwise by James Tiptree, Jr. (Ballantine Books, 1975). Cover by Don R. Smith

One note on the text — or texts — of the story. I first read “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” in Warm Worlds and Otherwise, her tremendous 1975 collection, one of the great single author non-retrospective collections in SF history. (It’s curious that she did not include the story in her first collection, Ten Thousand Light-Years from Home (1972).) It turns out that the text printed there, and in almost every other place since it first appeared, differs from the text as printed in the March 1969 Galaxy. I read through both versions (using the texts from the retrospective “best of” collection Her Smoke Rose Up Forever, and from that issue of Galaxy.) The changes are minor, but throughout the later version is a bit better.

For example: from the very first paragraph, Tiptree’s preferred version reads:

He almost turned back to speak, but he felt too tired: like nearly everyone else, he was fighting the flu.

The Galaxy version is slacker, to my mind, and slightly reduces the momentum Tiptree can generate:

If he had not had the flu like everyone else that autumn, he would have turned back to speak to Ain, but he shuffled on to his seat.

A bit later there was a completely changed sentence: “It was the dead time of the afternoon.” is replaced by “Smog shrouded the plane.” — the benefit here is just a bit more emphasis on pollution.

|

|

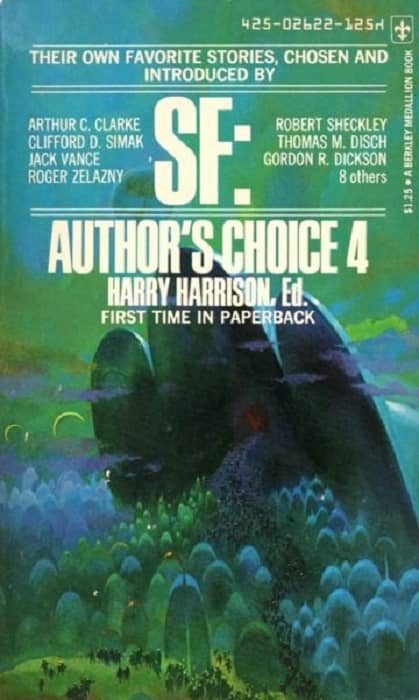

SF: Author’s Choice 4, edited by Harry Harrison (Berkley Medallion, 1974). Cover by Paul Lehr

And so it is throughout — small changes (not that many, really) that slightly improve the rhythm, quicken the pace, add a sharp detail. I suspect this is a case of Tiptree revisiting the early work (these changes seem to date to the 1974 version that appeared in Harry Harrison’s anthology SF: Author’s Choice 4) and seeing what she could have done better, though I’ve also seen it suggested that Pohl meddled with her manuscript.

Supposing instead that Tiptree made the revisions (which seems more likely) it’s another case (as with Le Guin’s revisions to “Winter’s King” discussed in this space a while back) of a more experienced author understanding how small changes can improve an already excellent piece.

|

|

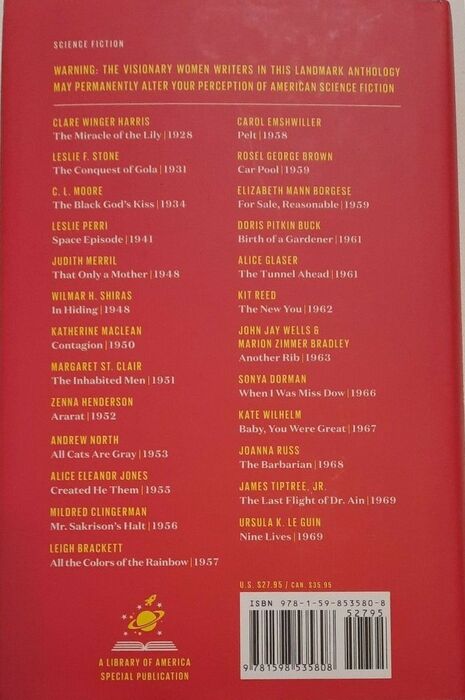

The Future is Female!, edited by Lisa Yaszek (The Library of America, 2018). Cover by Richard Avedon

[Thanks to Dave Hook for noticing the variant text and tracking it through several editions. The first reprint of the story was in SF: Author’s Choice 4, and it seems that every subsequent reprint except in the Library of America anthology The Future is Female! (edited by Lisa Yaszek, from 2018) uses the revised text.]

Rich Horton’s last short fiction review for us was Pushing Us Away from Gender-Based Assumptions: “Winter’s King” by Ursula K. Le Guin. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

Thanks for this, Rich. There is no SF author more essential to me than Tiptree/Sheldon. She never pulled a punch, and Her Smoke Rose Up Forever is a volume I’ve actively proselytized for. There is a place for Campbellian optimism (Ironic that her first sale was to him) but I find the Tiptree bleakness bracing and even, in its own dark way, exhilarating.

Indeed — Tiptree was truly one of the most bracing and exhilirating of writers. The list of great stories running from “The Last Flight of Dr. Ain” through, say, “Slow Music” is just astonishing.

In the works after that I think she did sometime pull her punches a bit — or perhaps wildly misaim them. But the core work is remarkable, and effectively bleak — it earns its bleakness.

This is a really excellent review/appreciation. I’m in the process of reading the biography and reading (or re-reading) stories as they are mentioned.