A Poisoned Bouquet: Fancies and Goodnights by John Collier

Fancies and Goodnights (Bantam Giant, 1953). Cover by Charles Binger

Fantasy, this genre that we love so much, is in reality not one genre but many; that’s one reason we love it. Any form that can accommodate the cynicism of Glen Cook and the lyricism of Patricia McKillip, that can hold the clarity of Robert E. Howard and the ambiguity of John Crowley, that can contain the brutality of George R.R. Martin and the hilarity of Terry Pratchett… well, there’s nothing it can’t do. Fantasy contains multitudes.

There’s a problem with being a member of a multitude, however — it’s easy to get lost, easy to be pushed to the back of the line by the ever-swelling mob of new books, new writers, new modes, easy to be misplaced or forgotten. It’s happened to many worthwhile writers. It’s happened to John Collier.

John Henry Noyes Collier, who died in 1980 at the age of seventy-eight, specialized in “slick” fantasy stories, “slick” because they generally appeared in “slick-paper magazines” as opposed to the cheap-paper pulps, upscale publications like The New Yorker, The Atlantic Monthly, or Esquire. Characterized by modern, urban settings, a sophisticated, often satirical tone, and the irony-laced employment of traditional figures such as witches, genies, angels, devils, magicians, and ghosts, slick fantasy flourished during the twenties, thirties, and forties, and manifested itself in many different media. The humorous supernatural novels of Thorne Smith such as Topper (1926) and The Night Life of the Gods (1931), plays like Noel Coward’s breezy mix of marriage farce and spiritualism, Blithe Spirit (1941), and films like René Clair’s screwball comedy, I Married a Witch (1942, and itself the progenitor of one of the most popular television series of the 60’s, Bewitched), are all examples of this effervescent mode. John Collier may have been its greatest prose practitioner.

Collier wrote a few novels (His Monkey Wife is probably the best known), but most of his output consisted of short stories for the aforementioned mainstream magazines. His tales were favorites of the folks who were in charge of television in the 50’s and 60’s when the anthology format was at its peak, and Collier’s work was adapted for the small screen time and again, especially for The Twilight Zone and Alfred Hitchcock Presents. (The Master of Suspense himself directed a dramatization of Collier’s story of domestic homicide, “Home for Christmas.”)

Alfred Hitchcock, Master of Suspense and John Collier Fan

In 1951, fifty of Collier’s best stories were collected in Fancies and Goodnights, which won both the International Fantasy Award and an Edgar Award from the Mystery Writers of America, as it also contains several of Collier’s acerbic tales of murder — in his view, an activity best kept in the family. (Marriage is a risky undertaking in John Collier’s universe, as it is in many others.) It’s a volume that no self-respecting fantasy or mystery collection is complete without.

Dip into it anywhere and you’ll come up with a delightfully sour treat, and in these stories literally anything can happen: a loving couple, each wishing to provide for the other in case the worst happens, take out exorbitant insurance policies on themselves… and wind up poisoning each other for the money (“Over Insurance”); a gorilla escapes from the zoo and becomes a celebrated author, but easy success and the corruptions of bourgeois life prove his undoing (“Variation on a Theme”); a devil is cured of his diabolism by a good psychoanalyst and ends as a solid, crosswalk-observing taxpayer with decidedly middle-class views on the loose morals of the younger generation (“Fallen Star”).

The very first story in the book gives a good idea of Collier’s sardonic method. “Bottle Party” begins thus:

Franklin Fletcher dreamed of luxury in the form of tiger-skins and beautiful women. He was prepared, at a pinch, to forgo the tiger-skins. Unfortunately the beautiful women seemed equally rare and inaccessible. At his office and at his boarding-house the girls were mere mice, or cattish, or kittenish, or had insufficiently read the advertisements. He met no others. At thirty-five he gave up, and decided he must console himself with a hobby, which is a very miserable second-best.

One day Fletcher listlessly wanders into a dingy antique shop. The shelves are stocked with dusty bottles, which the wizened proprietor assures him contain “various sorts of genii, jinns, sibyls, demons, and such things.” One supposedly even holds the most beautiful girl in the whole world. More out of boredom than belief, Frank winds up buying what the shop-keeper describes as a “good, all-round, serviceable” genii.

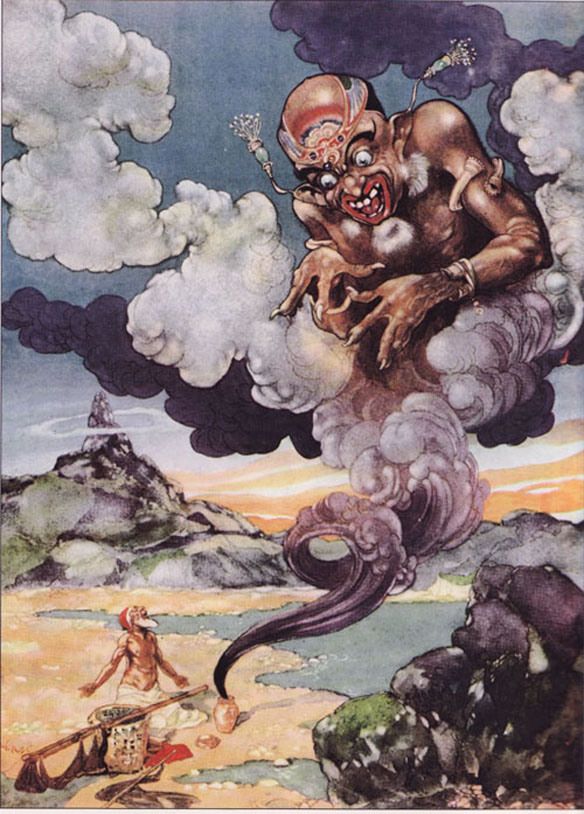

Unstoppering his purchase at home (the cost was a mere five dollars), Frank is delighted to find that he bought more than a bottle full of sales talk. He is now the owner of a powerful and (seemingly) obliging magical servant “six feet in height, with rolls of fat, a hook nose, a wicked white to his eye, vast double chins, altogether like a film-producer, only larger.”

Like a Film Producer, only Larger

In no time at all, Frank is lolling on a carpet in a genii-conjured palace with the most beautiful girl in the world at his side (fetched from the old man’s shop by his supernatural servant), but of course the genii and the inamorata soon decide that they don’t want to be at anyone’s beck and call, and so Frank winds up stuffed in a bottle himself (the same one that originally held the most beautiful girl in the world). His faithless ex-servant magically sends the bottle back to the old man’s shop, where it is eventually purchased by some sailors, and “when they unstoppered him at sea, and found it was only poor Frank, their disappointment knew no bounds, and they used him with the utmost barbarity.”

“Bottle Party” gets the book off to a great start, but the highest points among many high points in Fancies and Goodnights are to be found in Collier’s two most famous stories, “Evening Primrose” and “The Chaser.” Each one is like a beautiful, fragrant flower plucked from a nightshade bouquet, irresistibly alluring… and deadly.

In “Evening Primrose”, a literary artiste named Charles Snell makes a momentous decision: “I would turn my back for good and all upon the bourgeois world that hates a poet. I would leave, get out, break away –”

No Thoreau he, Charles doesn’t retreat to the woods to live in rustic asceticism; instead, he hides away in the bowels of an enormous department store, Bracey’s Giant Emporium, where, apparently unconscious of the irony, he will enjoy the luxurious fruits of the civilization he is ostensibly rejecting. (The narrative is in the form of Charles’ journal, found “in a pad of Highlife Bond, bought by Miss Sadie Brodribb at Bracey’s for 25 cents.”)

The night after setting up his sanctuary, “secure behind a towering pile of carpets,” Charles makes a startling discovery — he is not alone. When the lights are turned off and the watchman begins his solitary (and easily-timed) rounds, the others emerge. Far from having withdrawn from society, the disgruntled poet has merely entered another one. Many people have made the same decision that Snell made, it seems, though for their own particular reasons.

These dwellers in darkness have comfortably adapted to their peculiar life, enjoying bridge parties, theatricals (“tonight, Mrs. Brisbee’s little play, Love in Shadowland, is going to be presented”) and even interstore visits between members of different “colonies.” (Charles is told that “people live in all the great stores.”) Like all such groups, the store’s underground society has its customs, rituals, hierarchies, and taboos… and the penalties for violating them can be severe indeed.

Bracey’s Secret Society

Charles quickly befriends Ella, a young woman who was absorbed into the store’s colony years before when, as a little girl, she was separated from her mother during a shopping trip. Like any outsider who discovers the existence of the secret society, Ella was condemned to death and was only saved when Bracey’s aristocratic leader, Mrs. Vanderpant, decided that the child could be trained to be her maid. Had Ella not met this need, she would have been visited by the Dark Men, who come when needed from where they live in the city’s funeral homes, and who deal with all cases of natural death, burglary, or other unwanted intrusions. As Ella Tells Charles,

They go in, to where the dead person is, or the poor burglar. And they have wax there — and all sorts of things. And when they’re gone there’s just one of those wax models left, on the table. And then our people put a dress on it, or a bathing suit, and they mix it up with all the others, and nobody ever knows.

Charles falls in love with Ella, and when she determines to make contact with the night watchman and gain his help in escaping Bracey’s, Snell determines to join them, however slight their chance of success may be. He decides to leave his journal on a counter, where it may be discovered by a customer if they fail, in which case he urges his unknown audience to “look in the windows. Look for three new figures: two men, one rather sensitive-looking, and a girl. She has blue eyes, like periwinkle flowers, and her upper lip is lifted a little.”

The poet’s last words are a howl of rage — “Smoke them out! Obliterate them! Avenge us!”

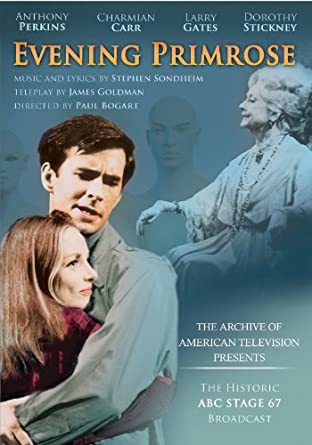

“Evening Primrose” (which was made into a musical for television in 1966, starring Anthony Perkins of Psycho fame, with music and lyrics by Stephen Sondheim) is an extraordinary story, striking notes satirical, romantic, macabre, and ultimately tragic. It’s no surprise the Stephen Sondheim who gave us Sweeny Todd was attracted to it.

Evening Primrose, 1966 television Version

Memorable as “Evening Primrose” is, Fancies and Goodnight’s last story, “The Chaser”, may be an even greater tour-de-force, making an unforgettable impact in a mere two and a half pages.

The tale takes place entirely within the confines of “a tiny room, which contained no furniture but a plain kitchen table, a rocking chair, and an ordinary chair. On one of the dirty buff-colored walls were a couple of shelves, containing in all perhaps a dozen bottles and jars.”

The story begins as Alan Austin, “as nervous as a kitten,” enters this room and presents its sole occupant, an old man sitting in the rocking chair, with “the card he had been given.” The old man politely tells his young visitor to sit down, and their ensuing conversation comprises “The Chaser’s” only action.

Austin begins by asking his host if it is true that “you have a certain mixture that has — er — quite extraordinary effects?” The old man good-naturedly replies that all of his products could be so described; none of them are in any sense ordinary. “I don’t deal in laxatives and teething mixtures.”

As an example of the unique nature of his stock, he gives an example: “Here is a liquid as colorless as water, almost tasteless, quite imperceptible in coffee, milk, wine, or any other beverage. It is also quite imperceptible to any known method of autopsy.”

The appalled Alan Austin, a bit slow on the uptake, asks if his host means that this mixture is a poison. “Call it cleaning fluid if you like,” the old man replies. “Call it a spot-remover.” He then mentions that for one teaspoonful of this extraordinary potation (an amount that is quite sufficient) he asks five thousand dollars. “Never less. Not a penny less.”

Even more appalled than he was a moment before, Alan asks if all of the mixtures on the shelves are that expensive. Certainly not, the old man assures him. “It would be no good charging that sort of a price for a love potion, for example. Young people who need a love potion very seldom have five thousand dollars. Otherwise they would not need a love potion.”

“The Chaser” on The Twilight Zone — Salesman and Customer

A love potion, of course, is just want Alan Austin has come for, as he quickly makes clear. A careful consumer, Alan has some questions for the salesman. Will the effects wear off? And precisely what will those effects be? The old man answers cheerfully and completely. The effects are permanent, and “extend far beyond the mere casual impulse. But they include it. Oh yes, they include it. Bountifully. Insistently. Everlastingly.”

The potion is a true love potion, engendering all the aspects of the emotion, both carnal and spiritual. Indifference will change to devotion, scorn to adoration, so much so that Diana (the young lady that Alan pines for) will fill the young man’s every moment with unwavering, unceasing, unrelenting attention:

How carefully she’ll look after you! She’ll never allow you to be tired, to sit in a draught, to neglect your food. If you are an hour late, she’ll be terrified. She’ll think you are killed, or that some siren has caught you… and, by the way, since there are always sirens, if by any chance, you should, later on, slip a little, you need not worry. She will forgive you, in the end. She’ll be terribly hurt, of course, but she’ll forgive you — in the end.

And there will be no escape from this… paradise, as Alan’s beloved will never divorce him, or give him any grounds for divorce, or even “uneasiness.”

An enraptured Alan asks how much such a “wonderful mixture” costs. It’s not as expensive as the “spot remover,” the old man replies. That is something that one has to be more mature to need; one has to have the desire and the discipline to… save up for it. No, the love potion costs “just a dollar.” As Alan pays the money and receives the potion, his host opines on his business philosophy: “I like to oblige… then customers come back, later in life, when they are rather better off, and want more expensive things.”

“The Chaser” on The Twilight Zone — Alan and Diana

As he bustles out of the shop with his purchase, an effusive Alan Austin bids his benefactor goodbye. “Au revoir,” the old man replies.

“The Chaser” is a perfect story, an allusive masterpiece in miniature. Every word does its ironic, sinister work, revealing to the reader (but unfortunately not to its besotted hero) the whole grim progress of Alan Austin’s subsequent love affair — a progress a bit too grim for Rod Serling and the Muckety-Mucks at CBS; when the story was adapted for the Twilight Zone’s first season, the ending was changed, with Alan unable to bring himself to remove his “spot”, instead hopelessly reconciling himself to a life of his beloved’s hellish affection.

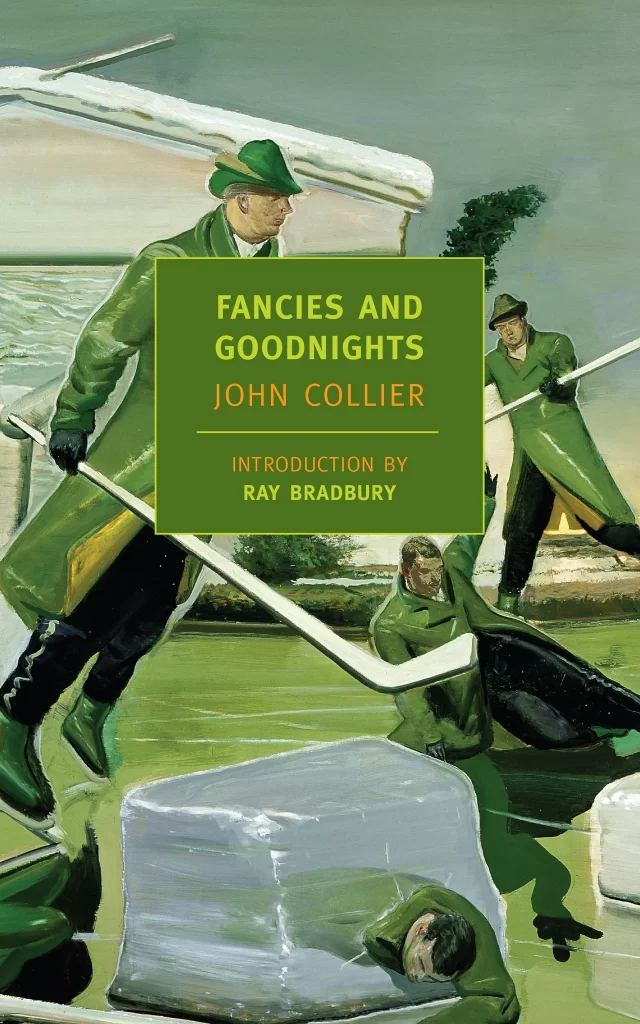

Fancies and Goodnights (currently available in a New York Review of Books edition with an introduction by Ray Bradbury) contains fifty such delightful, unique anti-epics, fantasies of frustration steeped in the minutiae of modern urban life, with its daily round of work, marriage, money, sex, and status seeking, each story enlivened by the often hilarious (but no less serious for all that) intrusions of murder, mayhem, and the supernatural.

Fancies and Goodnights (NYRB, 2003). Cover by Neo Rauch

Give these tales a try and odds are you’ll find them as addictive as perfectly salted peanuts; as soon as you finish one, you’ll reach for another, and you’ll discover that for you, John Collier is no longer one of the faded, forgotten faces of yesteryear; he now stands out from the crowd. You’ll remember him as he deserves to be remembered, as a master storyteller who still has something to say.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was Slapdash Slapstick: Ron Goulart, January 13, 1933 – January 14, 2022

I discovered Collier as a teenager and have reread his stories several times. The closest writer to Collier would probably be Roald Dahl.

Great collection. Up there with Roald Dahl’s “Kiss Kiss” and Fredric Brown’s “Nightmares and Geezenstacks” from roughly the same era.

That last line of Bottle Party had me LOL’ing for several minutes.

A wonderful, urbane writer whose pearlescent short stories were often the prize of whichever anthology I was perusing, many times one bannered as Alfred Hitchcock Presents. Along with other Anglo writers like H. H. Munro (“Saki”) or Lord Dunsany or Gerald Kersh, Collier had a way of taking the seemingly sophisticated prose of the stuffy literary “reviews” and turning it into a sharp-witted instrument to pare away the genteel surface of mundane society to expose the illogic within, making its lack of magic more bizarre than the supernatural incursions that came when their bottles were uncorked.

I’ve been awaiting this article for a while, and am delighted to finally read it. I agree that those are two of Collier’s best stories–although I enjoyed “Variation on a Theme” a bit more than I should have.