Twilight: 2000 Reflections

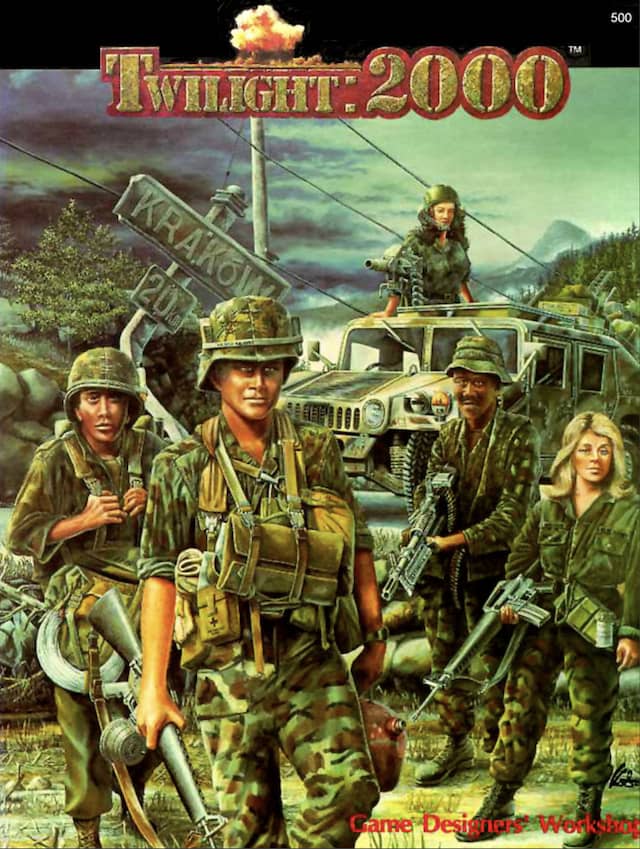

For Black Gate, I spent much of 2021 re-visiting Twilight: 2000‘s first edition adventures and sourcebooks. Twilight: 2000, published by GDW in the mid 1980s, absorbed into its setting much of the worries and fears of the late Cold War — but turned it into a game. The Soviet Union and China begin a war that eventually brings in the rest of the world. While the war is starts out as conventional, the temptation to use tactical nuclear weapons cannot be held back. The world inches across into nuclear Armageddon.

While Twilight: 2000 was not unique in suggesting a nuclear apocalypse, it did have a compelling twist that differentiated it from things like Mad Max or By Dawn’s Early Light: it happens in the immediate aftermath. Armageddon is happening — society is breaking down. National governments like the US or USSR exercise very little control. Environmental devastation is in the early stages. Yet people continue to live. Some even continue to fight the war. Most try to simply survive.

Of course, Twilight: 2000 is a roleplaying game. The players create characters and interact with the world. One of the more frequent words that appeared in my coverage of these adventures and modules was “sandbox.” But what does “sandbox” mean?

At its most basic, sandbox games give up the notion of a structured narrative story guided by the referee (Twilight: 2000s term for gamemaster or GM) to unstructured stories generated by random events. Roleplaying games have long relied on the use of random encounters. Early games included tables for traveling. Sometime nothing happened. Sometimes the players encountered goblins or dire wolves. In Traveller, entering star systems or traveling planetside is supported by a host of tables that allow for random encounters. However, these were often intended simply as encounters along the way to some destination — a temporary roadblock. While GMs could incorporate these encounters into the narrative of the story, they were not expected too. Kill the dire wolves, get a bit of loot, and move on.

Twilight: 2000 embedded randomness into the story as a feature — as a driving story element. Structured narrative stories can — not always — result in “railroading,” which is the opposite of sandbox play. Railroading is when the players are essentially forced into following the narrative path, stripping their characters of meaningful choices. “I need the players to visit this town to get this potion from the evil necromancer — but Sandy wants to go to this other town she saw on the map… I need to force Sandy not go there.” That kind of thing. It can be crudely applied or more subtle, but it removes player agency. (Published adventures that have a more definitive plot do not need to be railroads; rather, how the referee applies the adventure and deals with player actions most often determines how much agency the players have.)

However, people thrive with stories. An open ended, no goal in the game is boring in the end. It provides no compelling reason for the players to engage. New random event. Play it out. Next random event. Twilight: 2000 solved this for its game by providing a nebulous target: Get back home to the USA. The players, soldiers in the 5th Mechanized Infantry, are part of an offensive by NATO forces in the summer of 2000 that collapses, stranding the players in Poland behind enemy lines. The ominous last statement from their commanding officer, “You’re on your own. Good luck,” leaves the characters fending for themselves.

This sets the immediate next decision for the players, “You’re here. What do you do?” No cliched tavern to meet in and find out the next adventure (note, I think using a tavern is perfectly okay — but it is used a lot). In this tradition, the players encounter a mysterious figure who outlines some problem and is seeking adventurers who can help. They provide any number of tantalizing reasons to take up the challenge — gold, magic items, a ship, etc. This often includes a number of people or destinations to follow up on.

Players often, of course, come up with their own unique solutions or approaches. GMs need to be flexible, but the players have been given a clear goal to achieve — and usually what they do is in service of this. Many convention games are of this sort. My own Star Wars adventure that I have run a few times starts with them getting a mission by their commanding officer. Given that convention games are three to four hours and a single episode, clear goals and objectives are necessary to “tell the story.”

Twilight: 2000 dumps that. The referee turns to the players at the start of the game and says, “What do you want to do?” They have some data—they know from where they came, where they are currently, and a rough idea of the enemy forces arrayed against them. Once they make a decision, the random encounters start. As they travel across Poland — in whatever direction they choose — they encounter marauders, wild dogs, desperate villages, surviving NATO troops, hostile Soviet forces, etc. Each encounter is rife with opportunity and danger. It becomes part of the story. And this is key. It is not an obstacle to be overcome and forgotten as a way through the story. Instead, it becomes part of the narrative, the grander tale that is a roleplaying campaign. The marauder band the players either dodge or fight off becomes the same band terrorizing a small village, which the townspeople are willing to pay some fuel to the players to end.

The overarching campaigns — the Polish campaign, the American scenarios, the Return to Europe — all provide intermediate targets for the players. The Polish campaign largely operates as a path for finding their way back to Germany for the eventual boat ride back to the States, but this path is loose. The adventures are more sourcebooks for the areas, major factions, and area-specific random encounters. The adventures also take some effort to suggest a few different ways to deal with major decisions (do the players attempt to sell The Black Madonna? Or do they give it to any of the several major factions that look to possess it?), but they do not bake into their ending a particular or even few potential results. Yes, some are more likely than others, but its what the players do and how well they succeed at it that matter.

Sandbox play has a lot in common with what are referred to as hexcrawls, another style of gaming from the early days of roleplaying. Essentially, one has a map on which they overlay a hex grid. The grid’s size is correlated to a specific distance. As players explore the map — again, usually with no predetermined direction by the referee — random encounters may or may not happen. While a group does not need a hexcrawl to have an open sandbox campaign, the recent version of Twilight: 2000 by Free League incorporates both. As players engaged in the initial movement after the battle that strands them, they start exploring Poland — though they may refer to it as escaping for their lives.

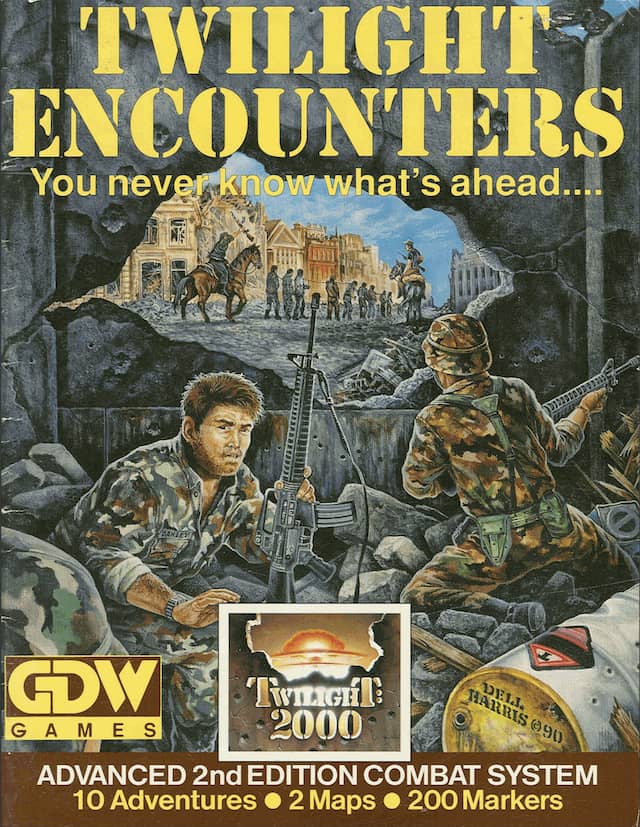

The initial impetus, of course, is to get out of the immediate area to avoid conflict with the Soviets or Polish troops. This is when they are likely to encounter marauders, a village, other US troops, wild animals, or more. Every adventure emphasizes this point by including those additional random encounter tables. The original game included more generic tables as a default, which Twilight: 2000 Twilight Encounters provides updated methods for. In the spirit of Traveller‘s world creation system, referees can roll up details about a village, including its size, organization, attitude, and current crisis. By rolling the dice (which can be done quickly and on the spot if needed), the players could encounter a village of 350 that are open to contact, desperately need a mechanic, and ruled by a popular council. Or… a major city of 60,000 that are hostile, facing a food shortage, and ruled by a warlord.

Twilight: 2000 Twilight Encounters also includes a modified combat system and a set of adventures that can be plugged into campaigns. These can be encountered via rumors, used as part of a random encounter, etc. While the combat system gets a thorough treatment, the heart of the book and the heart of Twilight: 2000 is in that last word: “encounters.”

The other adventures published by GDW to support the first edition of the game all read more like sourcebooks than adventures. Yes, they provide a basic plot thrust — a short term target for the players to engage with. However, the bulk of the material is providing the context and background for the area. The likely faction players will encounter. Rumors that provide not only hooks for engaging in that plot thrust but that can themselves lead to other adventures and encounters.

One of the awesome things about sandbox games — if embraced as intended — is that they provide opportunities for random connections. Yes, players will always do something that GMs and referees don’t expect, but sandbox games work with humanity’s innate capabilities of pattern recognition and narrative structure to bring a story together out of seemingly random things. This is also why they are fantastic for those who engage in solo or GM-less play. Free League has embraced wholeheartedly this sandbox notion with their latest version of Twilight: 2000 (and they’ve demonstrated similar sandbox hexcrawls in Mutant: Year Zero and Forbidden Lands).

As a final note, I have lived a long time with this game. It appeared in a time of my life where I had come to understand the nature of roleplaying games (versus my earliest forays into Traveller) and held special relevance to that historical context. The latest version of the game is weirdly historical — it takes place in the past for us living today. The original game took place in the true future. It posited a potential world that, frankly, in the mid 1980s did not seem all that implausible — even if it was unlikely. The fear of nuclear annihilation was real — and here was a game that allowed us to engage with that world without having to actually have Reagan and Gorbachev launch their respective nuclear arsenals. So yeah, a definite nostalgia for this game runs through my veins and for many people around my age. The setting is compelling and the in media res start to the whole game thrusts the players into the action, allowing the players and referee to generate unique, collaborative stories that only roleplaying games can do.

The latest version of Twilight: 2000 by Free League is a masterpiece of a game. A fantastic set of gritty rules updated and modernized for what we’ve learning about roleplaying games in the three decades since the first version of the game was released.

You can get the entire digital library of the first edition of Twilight: 2000 from Far Future Enterprises.

You can get the latest version of Twilight: 2000 from Free League.

Our previous coverage of GDW’s Twilight: 2000 includes:

Exploring Post-Apocalyptic Poland in Twilight: 2000

Twilight: 2000 — Roleplaying in a Post-Nuclear Holocaust World

Twilight: 2000‘s Polish Campaign, Part I

Twilight: 2000‘s Polish Campaign, Part II

Twilight: 2000‘s Polish Campaign: Part III

Going Home Isn’t All It’s Cracked Up to Be: Twilight: 2000’s American Campaign, Part I

From the Mountains to the Oceans: Twilight 2000‘s American Campaign, Part II

Reckoning: Twilight: 2000‘s American Campaign, Part III

Cruising in a Submarine: Twilight: 2000‘s The Last Submarine Campaign

Back to Where It All Began—Twilight: 2000’s Return to Europe Campaign

Surviving World War III in Iran

The State of the Unions: Twilight: 2000

Patrick Kanouse encountered Traveller and Star Frontiers in the early 1980s, which he then subjected his brother to many games of. Outside of RPGs, he is a fiction writer, avid tabletop roleplaying game master, and new convert to war gaming. His last post for Black Gate was The State of the Unions: Twilight: 2000. You can follow him and his brother at Two Brothers Gaming as they play any number of RPGs. Twitter: @twobrothersgam8. Facebook: Two Brothers Gaming.

Happy New Year (2000)! I hope that you will give us a peek at the Free League (Fria Ligan) version of Twilight: 2000 if you have continued on to that version of the game.

I find that the spectrum of “sandbox – railroad” is very much a matter of player perception and how it is managed by the referee. As you note, with no goals at all, boredom sets in. So, the ref is preparing threats for the player characters to face, and to make them credible, Bad Things will happen unless the PCs actively intervene. So I think that we can always get Sandy to the town with the necromancer and her potion, but it does need to be done much more with “carrots” of character choice than “sticks” of ref decree absolute (“All the roads in every direction are CLOSED, except this one”).

Hello and thank you for reading!

I really agree that the referee really sets the tone of the “sandbox-railroad” spectrum and that “carrots”–whether character connections, something interesting, etc., are the primary tools of the referee for sandbox games.

I did do a write up of the Alpha version of Free Leagues new version. You can read it here.

Thank you for the link to the earlier write-up on Fria Ligan’s version. I totally missed it! My bad.

When it comes to “sticks” in making characters stay on the “railroad” tracks (if really necessary), I find that a better way to do it is to invite the player to describe what “stick” would work. (“Yes, your character would never go on a quest to free the White Witch. Willingly. What would make it possible for them, even unwillingly? Saving their twin sibling?”)

Yes, using backstory or tie-ins like that are excellent. And agreed, asking them to provide it makes it all the more “stick” yet tastes like a “carrot.”