A Philosophical Policeman: The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare by G.K. Chesterton

Gabriel Syme was not merely a detective who pretended to be a poet; he was really a poet who had become a detective. Nor was his hatred of anarchy hypocritical. He was one of those who are driven early in life into too conservative an attitude by the bewildering folly of most revolutionists. He had not attained it by any tame tradition. His respectability was spontaneous and sudden, a rebellion against rebellion. He came of a family of cranks, in which all the oldest people had all the newest notions. One of his uncles always walked about without a hat, and another had made an unsuccessful attempt to walk about with a hat and nothing else. His father cultivated art and self-realisation; his mother went in for simplicity and hygiene. Hence the child, during his tenderer years, was wholly unacquainted with any drink between the extremes of absinth and cocoa, of both of which he had a healthy dislike. The more his mother preached a more than Puritan abstinence the more did his father expand into a more than pagan latitude; and by the time the former had come to enforcing vegetarianism, the latter had pretty well reached the point of defending cannibalism.

Being surrounded with every conceivable kind of revolt from infancy, Gabriel had to revolt into something, so he revolted into the only thing left—sanity.

The Man Who Was Thursday: A Nightmare (1908), by G.K. (Gilbert Keith) Chesterton, is a wondrous amalgam of thriller, mystery, boys’ adventure, and Christian allegory wrapped in a ripped-from-the-headlines tale of a cabal of anarchists plotting to blow things up. Gabriel Syme is a poet who fears the world is destined for destruction under a wave of moral relativism and nihilism. He is recruited to a special anti-anarchist unit of the British police by a mysterious figure who remains hidden in the shadows.

“I will tell you,” said the policeman slowly. “This is the situation: The head of one of our departments, one of the most celebrated detectives in Europe, has long been of opinion that a purely intellectual conspiracy would soon threaten the very existence of civilisation. He is certain that the scientific and artistic worlds are silently bound in a crusade against the Family and the State. He has, therefore, formed a special corps of policemen, policemen who are also philosophers. It is their business to watch the beginnings of this conspiracy, not merely in a criminal but in a controversial sense. I am a democrat myself, and I am fully aware of the value of the ordinary man in matters of ordinary valour or virtue. But it would obviously be undesirable to employ the common policeman in an investigation which is also a heresy hunt.”

Syme’s task is to go underground and join the Central Anarchist Council and uncover their plans. To do this, he tricks a real anarchist poet, Lucian Gregory, and is elected to the council in his place. There he is given the codename Thursday. The Council is comprised of six other men, all named for a different day of the week. They are a strange and unsettling group: “they all looked as men of fashion and presence would look, with the additional twist given in a false and curved mirror.” Most alarming of all is the man called Sunday, their president.

Syme had never thought of asking whether the monstrous man who almost filled and broke the balcony was the great President of whom the others stood in awe. He knew it was so, with an unaccountable but instantaneous certainty. Syme, indeed, was one of those men who are open to all the more nameless psychological influences in a degree a little dangerous to mental health. Utterly devoid of fear in physical dangers, he was a great deal too sensitive to the smell of spiritual evil. Twice already that night little unmeaning things had peeped out at him almost pruriently, and given him a sense of drawing nearer and nearer to the head-quarters of hell. And this sense became overpowering as he drew nearer to the great President.

The form it took was a childish and yet hateful fancy. As he walked across the inner room towards the balcony, the large face of Sunday grew larger and larger; and Syme was gripped with a fear that when he was quite close the face would be too big to be possible, and that he would scream aloud. He remembered that as a child he would not look at the mask of Memnon in the British Museum, because it was a face, and so large.

Following his elevation to the Council, Syme sets out to disrupt the anarchists’ plot to blow up the President of the French Republic and the Czar of Russia. As he sets out through London he realizes he is somehow being followed by Friday, the aged and decrepit Professor de Worms. His terror is relieved when he’s confronted by Friday, who informs him he is a police agent as well. What follows the revelation is a madcap trek across the Channel, through France, and back to England. There is a duel with an unwoundable man, cavalry charges, and car chases. An elephant, stolen from the London Zoological Gardens, is pursued by hansom-cab through the streets of Paddington and Kensington. Things are never what they seem; every event masked by something else, every face disguised. It all culminates in a dreamlike costume ball hosted by Sunday.

Following his elevation to the Council, Syme sets out to disrupt the anarchists’ plot to blow up the President of the French Republic and the Czar of Russia. As he sets out through London he realizes he is somehow being followed by Friday, the aged and decrepit Professor de Worms. His terror is relieved when he’s confronted by Friday, who informs him he is a police agent as well. What follows the revelation is a madcap trek across the Channel, through France, and back to England. There is a duel with an unwoundable man, cavalry charges, and car chases. An elephant, stolen from the London Zoological Gardens, is pursued by hansom-cab through the streets of Paddington and Kensington. Things are never what they seem; every event masked by something else, every face disguised. It all culminates in a dreamlike costume ball hosted by Sunday.

They were led out of another broad and low gateway into a very large old English garden, full of torches and bonfires, by the broken light of which a vast carnival of people were dancing in motley dress. Syme seemed to see every shape in Nature imitated in some crazy costume. There was a man dressed as a windmill with enormous sails, a man dressed as an elephant, a man dressed as a balloon; the two last, together, seemed to keep the thread of their farcical adventures. Syme even saw, with a queer thrill, one dancer dressed like an enormous hornbill, with a beak twice as big as himself—the queer bird which had fixed itself on his fancy like a living question while he was rushing down the long road at the Zoological Gardens. There were a thousand other such objects, however. There was a dancing lamp-post, a dancing apple tree, a dancing ship. One would have thought that the untamable tune of some mad musician had set all the common objects of field and street dancing an eternal jig. And long afterwards, when Syme was middle-aged and at rest, he could never see one of those particular objects — lamppost, or an apple tree, or a windmill — without thinking that it was a strayed reveller from that revel of masquerade.

The final pages of The Man Who Was Thursday reveal everything to have been some sort of Christian harlequinade, but then again, perhaps not. I admit to not being totally sure of the meaning of the book’s finale, even after reading comments written by Chesterton himself nearly thirty years after its publication. Nonetheless, this short novel is a magnificent work, for both its dazzling style and for the insane mechanics of the narrative. It has often been considered a precursor to the works of Jorge Luis Borges and Franz Kafka. As a model for tales of reality set askew and haunted by nightmares, it is perfection. The Man Who Was Thursday is never overtly fantastic. Every phantasmagorical or horrific event hides something prosaic and natural. And still, the whole book reads like the nightmare of its subtitle. By the end, what is real and what is only imagined is left unclear in a most superb way.

The final pages of The Man Who Was Thursday reveal everything to have been some sort of Christian harlequinade, but then again, perhaps not. I admit to not being totally sure of the meaning of the book’s finale, even after reading comments written by Chesterton himself nearly thirty years after its publication. Nonetheless, this short novel is a magnificent work, for both its dazzling style and for the insane mechanics of the narrative. It has often been considered a precursor to the works of Jorge Luis Borges and Franz Kafka. As a model for tales of reality set askew and haunted by nightmares, it is perfection. The Man Who Was Thursday is never overtly fantastic. Every phantasmagorical or horrific event hides something prosaic and natural. And still, the whole book reads like the nightmare of its subtitle. By the end, what is real and what is only imagined is left unclear in a most superb way.

Anarchism, a sort of libertarian Marxism, had become the bogeyman of the Western world in the decades leading up to the publication of Chesterton’s novel. The kings of Italy and Portugal (and maybe Greece), the Tsar of Russia, and President McKinley of the United States were all assassinated by anarchists. Bombs had been detonated around the world, killing dozens. For a man of such a conservative bent as Chesterton, anarchism was the perfect force for villainy in a novel, and for an artist and polemicist of his skill, it was something to help explore his ideas of the society he saw imploding around him.

To Chesterton, the real danger wasn’t from the bomb-throwing anarchist rank and file, but from those at the highest echelons. Modernity and the Western drift from faith had allowed all sorts of evil to seep into the world. Among the greatest was a bloody-minded nihilism; a disease of the wealthy and elite. As one character points out, the poor have an interest in not being governed badly, “the rich have always objected to being governed at all.” Their goals go far beyond merely doing away with government and capitalism.

What is this anarchy?”

“Do not confuse it,” replied the constable, “with those chance dynamite outbreaks from Russia or from Ireland, which are really the outbreaks of oppressed, if mistaken, men. This is a vast philosophic movement, consisting of an outer and an inner ring. You might even call the outer ring the laity and the inner ring the priesthood. I prefer to call the outer ring the innocent section, the inner ring the supremely guilty section. The outer ring — the main mass of their supporters — are merely anarchists; that is, men who believe that rules and formulas have destroyed human happiness. They believe that all the evil results of human crime are the results of the system that has called it crime. They do not believe that the crime creates the punishment. They believe that the punishment has created the crime. They believe that if a man seduced seven women he would naturally walk away as blameless as the flowers of spring. They believe that if a man picked a pocket he would naturally feel exquisitely good. These I call the innocent section.”

“Oh!” said Syme.

“Naturally, therefore, these people talk about ‘a happy time coming’; ‘the paradise of the future’; ‘mankind freed from the bondage of vice and the bondage of virtue,’ and so on. And so also the men of the inner circle speak — the sacred priesthood. They also speak to applauding crowds of the happiness of the future, and of mankind freed at last. But in their mouths” — and the policeman lowered his voice — “in their mouths these happy phrases have a horrible meaning. They are under no illusions; they are too intellectual to think that man upon this earth can ever be quite free of original sin and the struggle. And they mean death. When they say that mankind shall be free at last, they mean that mankind shall commit suicide. When they talk of a paradise without right or wrong, they mean the grave.

“They have but two objects, to destroy first humanity and then themselves. That is why they throw bombs instead of firing pistols. The innocent rank and file are disappointed because the bomb has not killed the king; but the high-priesthood are happy because it has killed somebody.”

When I consider that various heads of state were being murdered, that eugenics was becoming a fashionable subject, that educated men of Europe saw some sort of spiritual renewal in a general war, then I understand where Chesterton’s pessimism came from. His ability to turn that attitude around and fashion a sort of cri de cœur against the forces of darkness that never fails to be exciting or fun — or funny — is a testament to what he was capable of at his best. While he conceded most of his novels were better ideas than stories, The Man Who Was Thursday, he believed, was his most artistically successful.

Much of Chesterton’s writing is polemical in nature. At times it can be overwhelming but in this book it is synthesized completely with the narrative. He was definitely making a statement, but never at the expense of the frenzied rush of the story and his wonderful, riotous style. The Man Who Was Thursday is possessed of tremendous wit and joyful game-playing. If you haven’t yet, definitely give it a try.

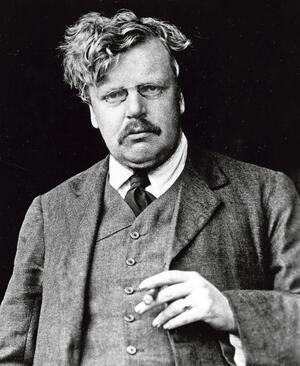

G.K. Chesterton has become a patron saint for a certain type of Christian (particularly certain Roman Catholics) of a snarky and pugnacious variety. This is due mostly to his great wit, his expansive interests, his style, and his critiques of modernity, as well as somewhat to his sheer, theatrical physicality — he stood 6’4″, weighed 286lbs, wore a cape, carried a sword cane, and drank copious amounts of ale.

G.K. Chesterton has become a patron saint for a certain type of Christian (particularly certain Roman Catholics) of a snarky and pugnacious variety. This is due mostly to his great wit, his expansive interests, his style, and his critiques of modernity, as well as somewhat to his sheer, theatrical physicality — he stood 6’4″, weighed 286lbs, wore a cape, carried a sword cane, and drank copious amounts of ale.

During his lengthy writing career, he produced a seemingly endless number of newspaper articles, poems, apologetics, and, of course, the Father Brown detective stories. His biography of Charles Dickens is credited with returning that author to the public eye after decades of neglect. I’ve read some of his theological and biographical works, as well as many of his short stories. I’ve enjoyed them immensely, but he’s not to be approached without some wariness.

Chesterton seems to have been incapable of seeing other ethnicities as anything other than alien. This translates to non-white characters never really rising above stereotypes in his works, with exaggerated traits and tropes the norm.

Whatever he was he was not a Frenchman; he might be a Jew; he might be something deeper yet in the dark heart of the East. In the bright coloured Persian tiles and pictures showing tyrants hunting, you may see just those almond eyes, those blue-black beards, those cruel, crimson lips.

He was a man fixated on the parochial and national, and for him, Jews could never become English but must always remain strangers. Perhaps, he argued, that while Jews should be able to participate in English society and politics at all levels, they should wear Middle Eastern garb so people would always know who they were. He spoke out against Hitler vehemently, but also said “I still think there is a Jewish problem.” He also spoke in favor of Zionism, largely because he felt the “Jewish problem” would be solved if they could all move somewhere else. He was associated with his brother Cecil, a noted antisemite, in attacking various businessmen and politicians involved in a stock scandal that took on enough of an antisemitic tack to warrant a successful libel case against Cecil.

I normally don’t write much about the politics and beliefs of the authors whose books I review. I don’t know them, never will, and really don’t care. If I rejected authors for their politics, there are very few books I’d be able to read. Nonetheless, G.K. Chesterton made his living speaking his mind about culture, politics, religion, and nearly everything else under the sun. His views were never merely personal; they were something he shouted and touted loudly and proudly. He’s also been mentioned for canonization. I’m not Catholic, but I guess I feel a little need to play devil’s advocate. But when someone hands you a Chesterton book, take it. There’s a good chance you’ll enjoy it. Just be forewarned that at times, in lieu of art and real human empathy, he settled for lazy and vile characterizations.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

It is a very great book (and though there are many editions, the Ignatius edition with annotations by Martin Gardner is the essential one), but not, I think, Chesterton’s greatest. I would argue that book is The Napoleon of Notting Hill. But either way, Thursday is a book that can stun, startle, bewilder – and tickle – you into deep thought on every page. There aren’t many books like that.

I enjoyed The Napoleon of Notting Hill but I do think The Man Who Was Thursday the greater, wilder, more mysterious novel. It’s a masterwork, and even though certainly not forgotten — still much praised, indeed — probably underrated.

Chesterton’s racial and ethnic attitudes were unquestionably distasteful and wrong, but, as Aonghus says, not those of a hater. But they could enable hatred in others of a different temperament — and he certainly tolerated the much more vile views of his brother Cecil and his friend Belloc, instead of trying to influence them.

I have to reread Thursday – it’s been a long time. I read the Napoleon of Notting Hill only a few years ago and was amazed by how good it was, and surprised by how little it’s talked about. Whichever is first and whichever is second, it’s a hell of a writer who can produce two books like that.

I used to adore Thursday, and still do, for its florid creativity and as a manic, headlong thrill ride barely held together by dream logic. But when I re-read it a couple of years ago, in the light of recent events the threats to civilization that Chesterton feared in 1908 now seem almost laughably feeble, the menace sadly miscalculated. But it’s still a great pleasure to read.

I don’t think relativism and nihilism have proved laughable threats, only not unaccompanied by others. I also think his joint worries over capitalism and statism were particularly prescient.

It must be said, though, that the notion of a secret society of anarchists infiltrated by undercover policemen to the point where there are no anarchists left, but only undercover policemen pretending to be anarchists, is one of the most brilliant premises of all time.

I haven’t read The Man Who was Thursday in years, so it’s interesting to note how the bomb-throwing anarchists have already been supplanted in the Father Brown stories by Communists and Capitalists (both whom are equally misguided in Chesterton’s opinion).

Was Chesterton a racist? I think he certainly had a funny attitude towards people of different ethnicities – there are a lot of Jewish characters in the Father Brown stories, and while Chesterton’s depiction of them isn’t openly hostile, I did find it a bit peculiar – and at the time, I wasn’t even aware of his opinions in this regard. I’m pretty sure the black chef in The God of Gongs would provoke an outcry today, though. In his defence, I don’t think Chesterton was a hater or would ever have endorsed the mistreatment of anybody based on their ethnicity – ie, I think he was a fundamentally kind person, for what that’s worth.

I agree with you on this, Aonghus. The anti-semitism is undeniably there (and is, I think, more attributable to the influence of Hillaire Belloc than that of his brother), but it was hardly unique to Chesterton; it was pervasive in the England – and Europe – and USA, for that matter – of a century ago. He died in 1936, so he didn’t live to see the final, unspeakable fruit that that attitude bore, but I believe that his basic decency and humanity would have led him to utterly reject the actions of the Third Reich.

Absolutely, Thomas. Antisemitism was rife prior to WWII (it seems to have been a feature of nearly every work of popular fiction from that era) and there’s no doubt in my mind that Chesterton would have unequivocally condemned the Third Reich and its ideology.

Perhaps not hateful, but lacking in some basic ability to perceive anyone different in any light other than “other.”

I love that book, have read it eight times beginning in 1975. Over the years I’ve gathered a library of about 4200 books. If I had to winnow them down to 400 books, or even fewer, The Man Who Was Thursday would remain in the collection.

I wonder if Jasper Fforde was satirizing some of the elements in this book for his Thursday Next series? Fforde’s main character is a policewoman named Thursday who can easily be said to belong to a “special corps of policemen, policemen who are also”– literary experts!!!