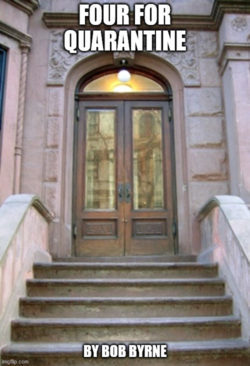

So, last year, as the Pandemic settled in like an unwanted relative who just came for a week and is still tying up the bathroom, I did a series of posts for the FB Page of the Nero Wolfe fan club, The Wolfe Pack. I speculated on what Stay at Home would be like for Archie, living in the Brownstone with Nero Wolfe, Fritz Brenner, and Theodore Hortsmann. I have already re-posted days one through twenty-one. Here are days twenty-two (April 12) and twenty-three (April 13). It helps if you read the series in order, so I’ve included links to the earlier entries. I enjoy channeling Archie more than any other writing which I do.

So, last year, as the Pandemic settled in like an unwanted relative who just came for a week and is still tying up the bathroom, I did a series of posts for the FB Page of the Nero Wolfe fan club, The Wolfe Pack. I speculated on what Stay at Home would be like for Archie, living in the Brownstone with Nero Wolfe, Fritz Brenner, and Theodore Hortsmann. I have already re-posted days one through twenty-one. Here are days twenty-two (April 12) and twenty-three (April 13). It helps if you read the series in order, so I’ve included links to the earlier entries. I enjoy channeling Archie more than any other writing which I do.

DAY TWENTY TWO – 2020 Stay at Home

No Easter parade. No church services. No family dinners at fancy restaurants. Things were very different this year. And speaking of fancy restaurants;

I don’t think I have mentioned that Rusterman’s is still open – sort of. A lot of places had simply locked up when the lock down order came. Sit-down dining was prohibited, so they decided not to struggle on. I’m sure a lot of them hoped that this whole thing would pass in a few weeks and they could reopen.

Quite a few restaurants shifted to carry-out and/or delivery only. And many of those couldn’t meet costs, and they closed: Probably for good.

And others have made it so far and are still trying to make it through. Rusterman’s is one of that group. Rusterman’s was run for years by Marko Vukcik, Nero Wolfe’s boyhood, and best, friend. Wolfe and I traveled all the way to Albania to find Marko’s killer and bring him to justice. In Marko’s will, Wolfe was made a trustee of the restaurant and for many years, he guided it well, though he eventually resigned that duty. Unfortunately, Rusterman’s, while still fine dining, went through a decline in the early 2000s, and Wolfe resumed his trusteeship. As you can imagine, he was quite demanding and the quality rose to previous levels.

We had ordered a dinner from Rusterman’s one Sunday, to support the cause and make sure it was still up to par. Wolfe found reason to grumble, but I thought it was fine. Delivering high-level cuisine can’t be easy.

Felix Martin was the manager, while William Dumfrey had come over from The Roosevelt to take on head chef duties. Leo ran the wait staff. I mention their names, because all of them were sitting in the office. I had put the red chair in the front room and moved three yellow chairs a proper social distance apart – and away from Wolfe’s chair and mine. Leo apparently didn’t feel far enough away, so he moved to the sofa.

Felix had called that morning and said that they needed to meet with Wolfe. I suggested a video conference, but they insisted on coming to the Brownstone. I don’t know that I could have convinced Wolfe to zoom, or skype, an entire discussion, so it was probably for the best.

…

Read More Read More