Indecent Exposure: The Driver’s Seat by Muriel Spark

Everyone is looking for something, and the things that most people are seeking are the easily identified, common currency of life, everyday ambitions like love, security, peace, wealth, happiness. But a certain select few are looking for… something else. That something else is the subject of the Scottish writer Muriel Spark’s 1970 novella The Driver’s Seat.

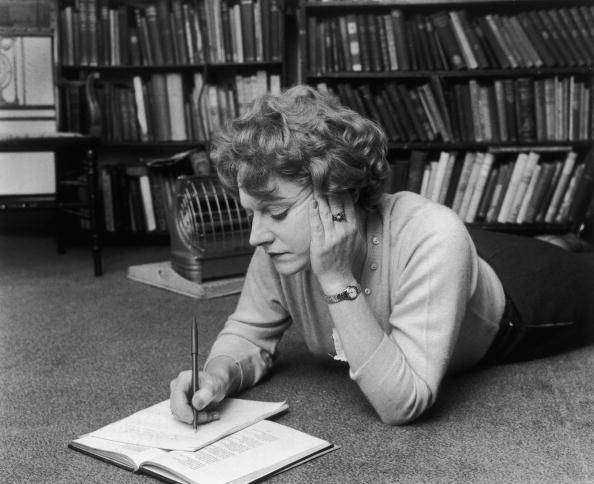

Someone once described being guillotined as experiencing “a short, sharp shock.” Leaving aside the question of how anyone could possibly know, that phrase is a perfect description of Spark’s novels and stories, each of which is as brief and cold and merciless as the nip of what the French once called the National Razor.

To name just a few examples, in Memento Mori an aging group of silly, self-obsessed men and women receive a series of mysterious phone calls in which an unfamiliar voice says one simple thing before hanging up: “Remember you must die.” Eventually some of them come to believe that their caller is not a prankster or a blackmailer, but is in fact Death himself.

In The Ballad of Peckham Rye a complacent, quiet village is visited by a charismatic young man who acts as a moral arsonist, maliciously wreaking havoc with the community’s every social relation, private and public, as if satisfying some diabolic commission. At the end of the story he calmly leaves behind the chaos he has engendered, with the air of having done the people of Peckham Rye a service.

In Spark’s best-known novel, The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie, a spinster schoolteacher at a 1930’s Edinburgh girl’s school acts as a Calvinistic God, shaping her students according to her eccentric whims, caressing and wounding them, elevating them and casting them down, until she sickeningly experiences her own unexpected damnation in the form of a betrayal by one of her prize pupils, the sort of “nasty surprise” Calvin’s Deity usually reserves for the non-elect, which is definitely not how Miss Brodie sees herself.

Even among such distinguished company, The Driver’s Seat stands out by virtue of its concision and its inexorable, dreamlike, increasingly terrifying progress to its strange and shocking end. Spark said that The Driver’s Seat was based on an incident that she remembered having read about in the news and further stated that the story was “supposed to give the reader nightmares.” She achieved her goal; in a career full of works with edges keen enough to draw blood, The Driver’s Seat may be the unkindest cut of all.

Lise is a young woman (“neither good-looking nor bad-looking”) in her early thirties who leaves her job in an accountant’s office for a holiday in the south. (It is never stated precisely, but Lise seems to be German and her vacation destination appears to be Italy, which was the case in the incident that inspired the book.)

From the moment we first meet her as she shops for vacation clothes, it is apparent that something is not quite right with Lise; something is out of balance. She seems delighted with the dress she has chosen and is on the point of buying it — until the salesgirl mentions that the material is a specially treated fabric that won’t stain. The implication that she could be so careless as to spill anything on her clothes causes Lise to fly into a rage and almost literally rip the dress from her body before storming out of the shop. The mere thought of ever losing control (even in such a trivial matter as eating) makes her lose control. (Lise’s misdirected intensity is apparent even in her fashion choices; all through the story she wears outrageously clashing colors with no awareness of how they draw the amused — or even contemptuous — attention of onlookers. In every way, she is a woman of extremes.)

As we follow Lise on her holiday, it soon becomes apparent that she is looking for something, or more precisely, someone, some as-yet-nameless person who will fulfill her deepest desires. As, with mounting and barely suppressed hysteria, she restlessly pinballs through airports, shops, parks, and city streets, she never stops searching. Spark periodically punctuates this quest with sudden flash-forwards, brief and brutal:

She will be found tomorrow morning dead from multiple stab-wounds, her wrists bound with a silk scarf and her ankles bound with a man’s necktie, in the grounds of an empty villa, in a park of the foreign city to which she is traveling on the flight now boarding at Gate 14.

Must Lise’s desperate search lead to such a tragic end? What a sad irony if a desire for companionship, connection, and love has such a grim conclusion. Well, yes and no, for it quickly becomes clear that Lise is not in any conventional sense looking for a soul–mate, a man who will sweep her off her feet, cover her with kisses, and carry her off to his castle as in a Harlequin Romance. No. She is seeking, not for her life’s fulfillment but for its ending; what Lise is looking for with such grim intensity and singleness of purpose is the man who will murder her, and when she finds him she will see to it that he does the job and does it right.

Eventually Lise finds the instrument she needs, a disturbed young man who has recently been released from a mental hospital for some unspecified sexual crime. She actually first sees him at the airport as she boards the plane for her vacation flight, which he is also taking. Lise instantly feels that this is her man, but when she takes the seat next to him he is instinctively terrified of her, and flees in a near panic to a distant part of the plane. Like calls to like however, and this pair, both of them equal parts murderer and victim, will meet again in the unnamed city that is their final destination, and the second time neither is destined to escape.

Consummation will come in a darkened and deserted villa, and even at the moment of her death Lise is determined to remain in the driver’s seat, her hands firmly on the wheel as she dictates to her killer exactly what he is to do to her. In a bleak bit of irony, despite telling him that she doesn’t want any sex (“You can have it afterwards”) he rapes her anyway before stabbing her in the neck “with a turn of the wrist exactly as she instructed.”

By the end of this stunning story, as the young man flees the scene of the murder, he sees already

the sad little office where the police clank in and out and the typewriter ticks out his unnerving statement: ‘She told me to kill her and I killed her. She spoke in many languages but she was telling me to kill her all the time. She told me precisely what to do. I was hoping to start a new life.’ He sees already the gleaming buttons of policeman’s uniforms, hears the cold and the confiding, the hot and barking voices, sees already the holsters and epaulets and all those trappings devised to protect them from the indecent exposure of fear and pity, pity and fear.

What is The Driver’s Seat, aside from a riveting, deeply disturbing fiction? Is it a crime story? A horror tale? A macabre joke? A work of psychological suspense, a Dostoyevskian descent into madness? A steel-hard, ice-cold parody of a romance novel? An acid-etched assessment of modern life with its rootlessness and alienation? A feminist critique or a critique of feminism? A savage satire of a consumer culture in which one can shop for anything, even one’s own death? All of these aspects and more are present, but ultimately such labels don’t really matter. Categorizing is itself a distancing, protective device, giving us a comforting way to shield ourselves from “the indecent exposure of fear and pity, pity and fear.”

It is best to set such buffers aside and let the work have its way with us, and surely Muriel Spark’s intention in writing her superb book was to make us feel the knife ourselves, hot in our own hands, cold in our own throats, trusting that the appropriate measures of fear and pity would follow. In that she succeeded to a discomforting degree. The Driver’s Seat (which was made into a truly awful movie with Elizabeth Taylor, of all people, as Lise) may or may not give you actual nightmares, but I guarantee that it will literally haunt you; reading it is an experience you will never entirely shake off. You have been warned.

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was My Robert A. Heinlein Problem.

Yes — THE DRIVER’S SEAT is a scary dark novel indeed. Not my favorite Spark — probably because the characters were so unpleasant (which was the point, I get it!) I like MEMENTO MORI a lot, and also the later LOITERING WITH INTENT, plus THE GIRLS OF SLENDER MEANS, PECKHAM RYE, and of course MISS BRODIE. (Speaking of unpleasant people!)

I figured that if I got any comments at all on this, I would get one from you, Rich! At this point I’m far from being a Spark completist, but I may be one before I’m done. I’ve found everything that I’ve read by her to be darkly compelling and worth multiple rereads.

It’s interesting how reviewers on Goodreads have widely differing interpretations of ‘The Prime of Miss Jean Brodie’. Some people see her as a villain, others as a victim of the establishment. Maybe because Spark never lets us know how she feels about her creation. Are we looking at a re-working of the gospels here? (Sharpe was a devout Catholic) Or an allegory about nazism? You tell me.

You’ll notice that I made no mention of Miss Brodie’s admiration of Mussolini, Aonghus. Her incipient fascism was a bit much to work into a one paragraph summary of a book that’s just providing background for an entirely different novel. I know how Goodreads feels – I’m not sure what I think about Miss Brodie myself, and I think you’re right about the reason. Everything I’ve read by Spark completely lacks any of those “this is how I feel so this is how you should feel” markers that infect so much fiction these days. Maybe that’s one reason I like Spark so much.

I think it was quite deliberate – and to her credit. To draw a random corollory – ‘The Maltese Falcon’ never lets us know what’s going on in the characters’ heads. Maybe this is why most of us remember what Sam Spade actually looks like? As opposed to, say, the continental op? In any event, it makes for a very gripping story because we’re never entirely sure what’s going on, or what Spade is up to.

Apologies btw. I appreciate my comment was off-topic. It was actually intended for Rich, who naturally assumed Brodie was the villain of the story. I’d assumed the same, but Goodreads suggests not everybody might agree.

I think Miss Brodie is pretty clearly a terrible person, and Spark, as you note, doesn’t TELL us that — but she shows us. And it takes a while for us to figure that out.