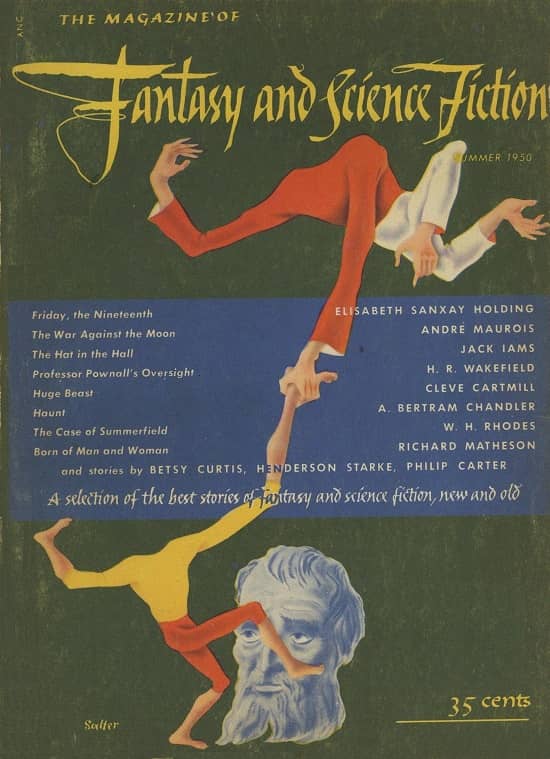

Retro-Review: The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, Summer 1950

The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, Summer 1950. Cover by George Salter

This was the third issue of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, though only the second under that name. (The first issue, Autumn 1949, was titled The Magazine of Fantasy.) Here we see it in the classic form of its early years… Whimsical fantasies… reprints from the 19th and early 20th Century, often by prominent writers … modest essays into not very hard SF… a real attempt to find good SF and Fantasy from writers in other genres.

And, I might add, covers by George Salter. Salter (born Georg Salter in Bremen, Germany, October 5, 1897 (so I share a birthday with him!) contributed 9 covers in the first two years of F&SF, then 2 more (in 1955 and 1966) — his illustrations were very much in the spirit of the early F&SF, somewhat whimsical, semi-abstract, clever. I like them a lot, though I know that taste isn’t shared by everyone.

Early F&SF was light on features. This issue featured only one… “Recommended Reading,” by the editors (Anthony Boucher and J. Francis McComas.) This was published just as genre SF was beginning to be widely published in book form. The recommendations include two Heinlein books (Sixth Column from Gnome, and Waldo and Magic, Inc. from Doubleday), as well as an anthology from Judith Merril, a couple of books from outside the genre, and more… if I am to be honest, none of the books mentioned are really all that memorable, save perhaps the Heinleins — and those more because they are Heinlein books, rather than because they are particularly outstanding.

The rest of the TOC is stories (and one short poem):

“Friday, the Nineteenth,” short story by Elisabeth Sanxay Holding

“Huge Beast,” short story by Cleve Cartmill

“The Hat in the Hall,” short story by Jack Iams

“The War Against the Moon,” novelette by André Maurois (trans. of Le chapitre suivant)

“Dumb Supper,” short story by “Henderson Starke” (Kris Neville)

“Ounce of Prevention,” short story by “Philip Carter” (Paul A. Carter)

“Death’s Jest-Book (excerpt),” poem by Thomas Lovell Beddoes

“The Case of Summerfield,” novelette by W. H. Rhodes

“Divine Right,” short story by Betsy Curtis

“Born of Man and Woman,” short story by Richard Matheson

“Professor Pownall’s Oversight,” short story by H. Russell Wakefield

“Haunt,” short story by A. Bertram Chandler

I bought this issue (from Curt Phillips at the Windy City Pulp and Paper convention) for one story — Elisabeth Sanxay Holding’s. Holding was a major mid-century writer of noir fiction, one of a series of great women noir writers who were often somewhat ignored. (Though not entirely ignored, and some first rate male noir writers were also underrated until later: witness Jim Thompson and Chester Himes. That said, the women seemed to get less notice, but in recent years the likes of Margaret Millar, Patricia Highsmith, Craig Rice, Dorothy B. Hughes, and Vera Caspary have come back into wider view.) Holding began her career in the ’20s writing romance, but turned to crime fiction later. She wrote 18 crime novels, four romances, one YA fantasy, and of course short fiction. She died in 1955, aged only 65.

“Friday, the Nineteenth” is a striking darkish fantasy. Donald Boyce is tired of his wife Lilian, and ready to have an affair with his best friend’s wife Molly. The story details the friction between Donald and his wife, and also Donald and Molly flirting at a couple of gatherings. The overall picture of Donald is not complimentary… whatever issues he has with Lilian seem more a product of his attitude than her failings. Anyway, Donald and Molly make a date for a drink after work one Friday, and agree to a rendezvous for more than just a drink the next day… and then things get strange. For next day is Friday again… This is a pretty fine story, with a real touch of eeriness by the end.

Cleve Cartmill has a curious sort of fame in the SF world, centering around one story that is generally considered to be terrible (even by Cartmill.) This is “Deadline,” which famously led to John W. Campbell, Jr., getting a visit from the Counterintelligence Corps to determined if he was leaking atomic secrets in his magazine. No action was taken — the details of the atomic bomb revealed in the story were all from public sources (and were apparently supplied by Campbell to Cartmill) and it seems that Campbell, delighted by the whole affair, exaggerated its importance in following years.

Cartmill is on the whole a very minor figure, even if the run of his work was at least better than “Deadline.” Indeed, though I’m not familiar with much of his work, other readers were quick to defend some of it — suggesting that though he was indeed a minor writer, and often clumsy, he was capable of solid work. “Huge Beast” is minor too, but amusing, if predictable. A researcher manages to attract a strange small furry animal, and he soon learns it came from a human starship that just returned from the animal’s planet. Why the animal is there is quickly guessed, but, as I said, amusing, and the mordant ending is well worked out.

Jack Iams was a journalist and a writer of crime fiction, fairly well-known in the ’40s and ’50s, but, at least to me, little-remembered now. I suspect Anthony Boucher’s background as a writer and prominent reviewer of mysteries (and perhaps Mercury Press’s focus on crime fiction) contributed to F&SF getting stories from the likes of Iams and Holding. “The Hat in the Hall” is a brief and entertaining piece about the aftermath of a party, in which the hosts find an unclaimed hat and ask a neighbor whose it might be. The answer is of course the fantastical element. Minor but worth its 1500 or so words.

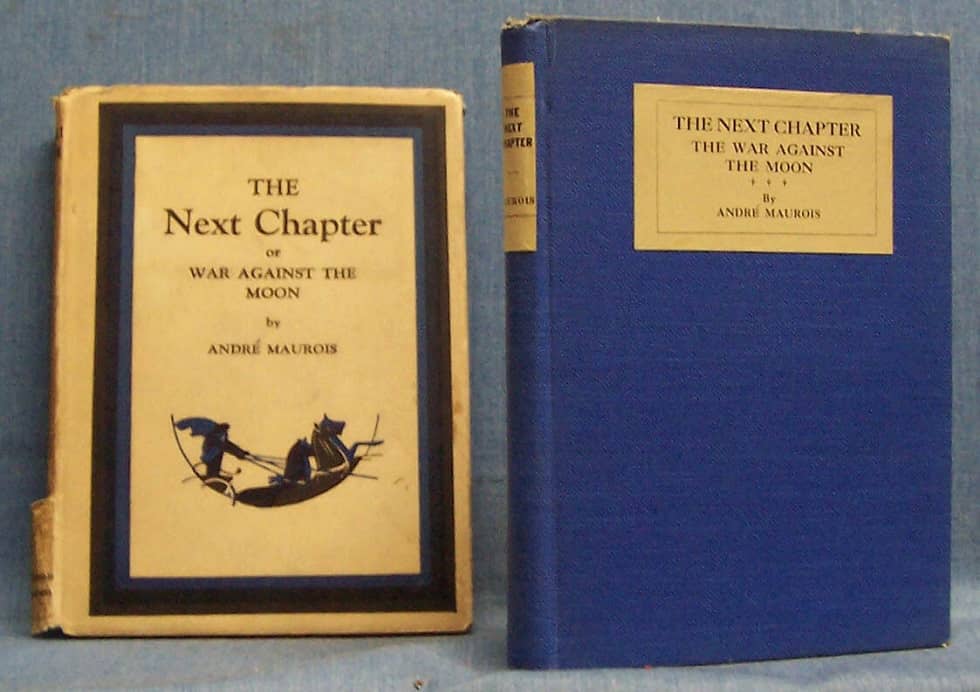

The War Against the Moon (E.P. Dutton, 1928)

Andre Maurois’s “The War Against the Moon” was first published as a (very slim) book by E. P. Dutton in 1928, part of a series called “Today and Tomorrow.” The “Today and Tomorrow” series was actually initiated in the UK, by the publisher Kegan Paul, and comprised over 150 “speculative essays,” apparently mostly on SFnal ideas. It appears to have been well-regarded at the time. Maurois’s contribution is not an essay, but a fictional extract from a supposed encyclopedia published in 1992. It discusses events of 1962 and later, by which time the world had mostly recovered from the disastrous effects of the Second World War (placed here as occurring in 1947, and said to have resulted in 30,000,000 deaths.) After that war, it seems, newspaper magnates from around the world secretly plotted to manipulate the news in order to maintain world peace. All this is threatened by the invention of a “wind accumulator,” which (shades of Kim Stanley Robinson’s windmills in Red Mars!) will provide energy for the world — but which will cause conflict because of the sudden increase in real estate values of remote windy places plus the loss of jobs in traditional energy industries. So the secret rulers of the world decide to invent a purely fictitious race of evil Moon creatures, claim they are attacking Earth, and thus attack the Moon — and distract everyone from the Earth-based conflicts. All this seems to work — except, what if there really are Moon creatures? Who don’t take kindly to an unprovoked attack! This is a clever satirical piece, and in some ways quite prescient (though not very believable scientifically.) I’m a little surprised it’s not better known — thought maybe it is and I’m just showing my ignorance.

“Henderson Starke” was a pseudonym Kris Neville used three times — I’m not quite sure why. The three stories (all of which I’ve read) are all fine work, and quite different to each other, so I don’t think he was either sloughing off weak stuff under another name or using the name for a particular style of pieces. (Though Barry Malzberg suggests perhaps that because those stories (the others are “Casting Office” and “As Holy and Enchanted”) are all fantasy (if highly varied fantasy) perhaps that is the link that explains the pseudonym.) “Dumb Supper” is set in the Ozarks (the only geographical hint is a mention of Joplin, MO) and the main character, Rosalynn, is a teenage girl who has just moved there and is trying to fit in. So she agrees to host a “dumb supper,” said to be a tradition — a supper with strict rules of conduct (doing everything backwards), and supposed harsh consequences for a failure to follow rules exactly. The supper may reveal your future husband (an issue that concerns poor awkward Rosalynn a good deal) … and the conclusion is expectedly dark.

|

|

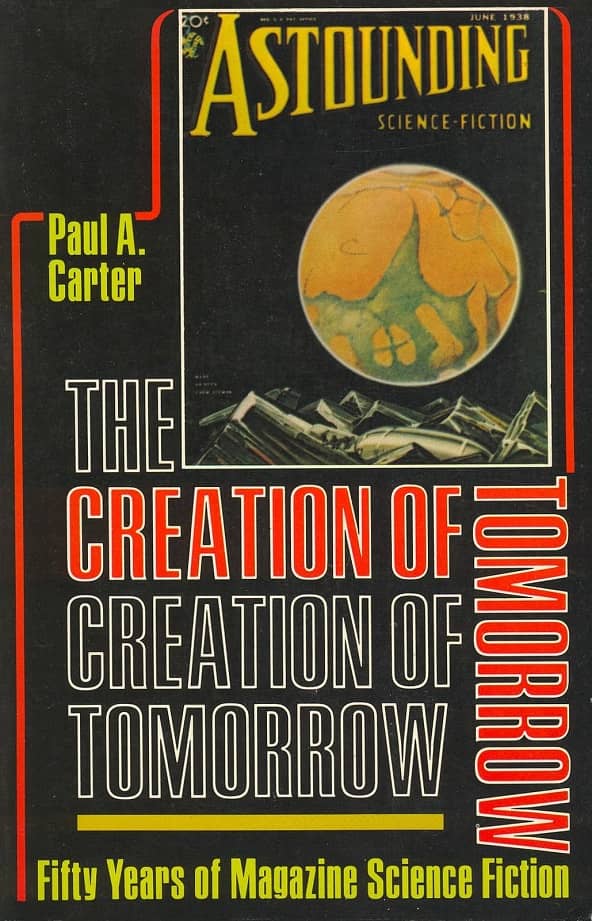

The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction (Columbia University Press, 1977)

Philip Carter’s actual name was Paul A. Carter, and I have no idea why this story was published as by “Philip” — the rest of his work was all under his real name. His first sale was to Astounding in 1946, when he was only 19. He published only ten more stories, over the next five decades. One was a short novel, Iceborn, in collaboration with Gregory Benford. Surely one of the stranger career arcs I’ve seen. He also published a significant book about Science Fiction, The Creation of Tomorrow: Fifty Years of Magazine Science Fiction, from Columbia University Press in 1977. “Ounce of Prevention” concerns the sole survivor of a mission to Mars, that left just as the Earth was embroiled in a nuclear war. (Remember the iron rule of ’50s SF magazines — it was a requirement that every issue have at least once nuclear war story. This one has two, or three if you count the ambiguous Maurois story.) The survivor is rescued by Martians, who have a strange offer: they can send him back to Earth, and back in time, with the chance to prevent the nuclear war. And this happens, with some setbacks, until a final mission — that to my mind seemed to result in a rather lame conclusion. Still, the central idea and its initial working out seemed a bit original.

As I noted, F&SF in its early years published lots of reprints, of what could be called proto-science fiction, as well as tasteful literary fantasy (often ghost stories.) This issue has two examples on the SF side, and one ghost story. “The Case of Summerfield,” is SF, by W. H. Rhodes. Rhodes (1822-1876) was a California lawyer who published occasional stories and poems under the name “Caxton” (perhaps a reference to William Caxton, who produced the first printed English books.) Evidently a few of these stories were SF, and the best known of these is this piece. It was published in a newspaper in 1871, and caused a sort of “War of the Worlds” sensation, leading to the publication of the second half.

The story itself is just OK. Leonidas Parker, a respected lawyer in California, was seen causing an old man, Gregory Summerfield, to fall from a train, killing him. Yet he is acquitted of any crime. But public opinion convicts Parker, so Parker tells the whole story — Summerfield, a man he had known when young, has come to Parker demanding a lot of money in exchange for a secret he has uncovered: how to make all the water in the world burn (by separating and recombining the oxygen and hydrogen, I assume — of course, the idea is scientific nonsense. But I thought of Vonnegut’s Ice 9 (from Cat’s Cradle) in this context, and I do wonder if Vonnegut knew this story.) Parker, convinced that Summerfield will indeed destroy the world if denied the money, but disgusted by this attempt to blackmail the world, decides he must kill Summerfield. So ends, the first half — the second half concerns what happens when a couple of people decide to search for Summerfield’s body to find his secret, and try to get rich in the same way Summerfield did. This second part seemed less convincing.

Betsy Curtis (1917-2002) was a fan, fanzine editor, and writer of about 16 stories that appeared between 1950 and 1973. Her best known story is probably “The Steiger Effect” (1967), which got a Hugo nomination. “Divine Right” was her first sale. It’s got a familiar plot, but handled pretty well. It’s set on another planet, colonized by humans, and ruled for a long time by a family of telepaths, who tyrannize the population by reading their thoughts and knowing if anyone is plotting against them. It’s tribute time, when everyone must give the King money or valuables, and this particular King seems to be demanding more money — for wasteful things — than his predecessors. Young Tod has just saved enough on his paper route to buy a new bike … and now it seems he must give his bike to the King. So what happens when he refuses? The course of events is predictable, and the story is kind of thin on believable details — truly minor work, but competent.

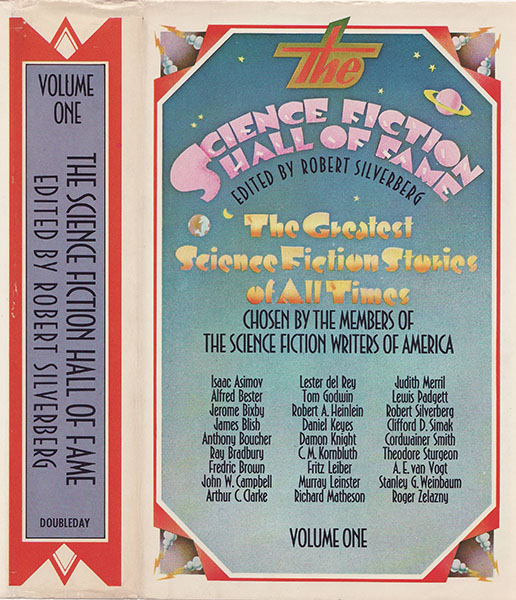

The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume One (Doubleday, 1970)

Richard Matheson’s “Born of Man and Woman” is the truly famous story here. It was Matheson’s first sale, and made a big impact, ending up in The Science Fiction Hall of Fame, Volume I. (It also was well enough known that a teacher read it to my class in 4th grade or so.) It’s a short tale told from the point of view of a child imprisoned in his parents’ basement, horrifying enough from the go but getting creepier, sadder, and scarier as we learn more about this child’s true nature.

Another reprint is “Professor Pownall’s Oversight,” by H. R. Wakefield. Wakefield (1888-1964) was an English writer, known for his ghost stories above all — four novels and several collections. This story is reprinted from his first collection, They Return at Evening, from 1928. It’s a chess story, about a man who feels cheated throughout his life by a classmate who is better than him at everything — but chess. And so he decides to use chess to bring about his enemy’s downfall — and in so doing, as we expect from such a story, brings doom on himself. Pretty nice stuff.

The final story is “Haunt,” by A. Bertram Chandler. It’s another Nuclear War story of sorts, but a bit different, in that it tells about the actual nuclear war — the bombing of Japan. And from a quite different point of view. It’s curiously framed: it’s a bar story, and also tangentially a story of the Rim (Chandler’s Rim, that is, used in most of his novels), and also a story aimed at a punning last line. Good enough work, not brilliant.

Rich Horton’s last short fiction review for us was “It Opens the Sky,” by Theodore Sturgeon. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.