Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords: The Year of Shogun

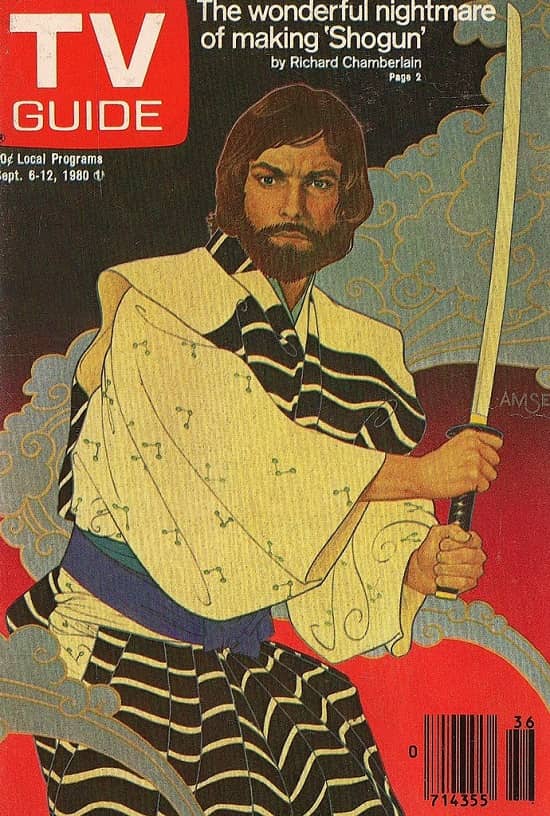

TV Guide featuring Shogun (September 6-12, 1980)

Before 1980, few people in America and Europe knew much about Japan’s samurai era — if anything, they associated its warrior ethos with the hostile mindset that had led the country into its big mistake in World War II. The unarmed combat skills of judo and karate had been popularized during the Sixties, but little was known about the martial arts of the samurai that had preceded them until Shogun, James Clavell’s blockbuster novel and subsequent hit TV miniseries, hit the American and European mainstream.

Suddenly samurai were top-of-mind for mass market consumers, from low-culture exploitation videos (as they were regarded then) like Shogun Assassin to high-culture art-house darlings like Kagemusha, the triumphant return of director Akira Kurosawa to the genre of his breakthrough film Seven Samurai. After 1980, “samurai” was nearly as recognizable a historical concept as “cowboy.”

Shogun

Rating: ***

Origin: USA, 1980

Director: Jerry London

Source: Paramount DVDs

Dude. Nine hours.

If you were alive in 1980 and over the age of 10, you probably watched this blockbuster TV miniseries along with everybody else in America and Europe. For American TV of its time, it was daring for its treatment of adult themes, and it introduced most viewers to the samurai period of Japanese history, which up till then had been rarely depicted in western mass media. Afterward the broadcast, James Clavell’s novel, on which it was based, sold over two million copies in paperback. (I bought one.)

It hasn’t aged well. Viewed forty years later, this is a slow, talky soap opera set against historical events that are never clearly explained, a backdrop of samurai politics that’s murky at best. Only a few of the many characters are portrayed in enough depth to make them interesting, giving the viewer little investment in whether they come or go. And though there are ninjas, and a lot of talk about what it means to be a samurai, there’s not much samurai action in all those nine hours, and what there is doesn’t compare well with Japanese jidaigeki films made around the same time.

Clavell’s novel is a fictionalized account of a true story, that of William Adams, an English navigator shipwrecked on the shores of Japan in 1600, when the country was completely unknown to Europeans save for a few from Portugal and Spain. This English pilot, here called John Blackthorne (and played by Richard Chamberlain), has to negotiate the strange and deadly culture of the samurai with no knowledge of the society or language, his seafaring skill making him a pawn in conflicts between warring daimyo until he is taken up by the wily Lord Toranaga (Toshiro Mifune). Toranaga is served by the Lady Mariko (Yoko Shimada), who has learned European language from Portuguese Jesuit missionaries, and she becomes Blackthorne’s guide to Japanese ways — and eventually his lover, despite Mariko being married to one of Toranaga’s leading retainers.

Much angst ensues. Chamberlain as Blackthorne is regularly gobsmacked by the harshness of samurai culture, staring in consternation with furrowed brow as events beyond his control unfold in front of him. After a career in Sixties TV shows, in the Seventies Chamberlain had graduated to B-level leading roles in the movies, mainly historical adventures in which he acquitted himself well. Shogun made him a top star, but it’s far from his best work. The Japanese leads come off better: Mifune oozes gravitas and sly humor as Toronaga, while Shimada as Mariko delivers a complex and moving performance that steals every scene from Chamberlain. A few of the supporting actors are memorable as well, particularly John Rhys-Davies (you know him as Gimli) playing Spanish navigator Rodrigues, and Frankie Sakai as one of Toranaga’s vassals, Lord Yabu.

But the pacing plods for most of the miniseries, and after running on for so long, it wraps up with an abrupt and unsatisfying ending. Production values are okay, but still below the quality of feature films. The show does make one bold move by refraining from translating the spoken Japanese except when re-spoken by one of the European-speaking interpreters, which effectively conveys Blackthorne’s incomprehension when suddenly immersed in a foreign culture. However, sometimes no interpreter is around to explain events conveyed in Japanese, necessitating voice-over to explain things, an awkward imposition that’s partly forgiven because they got Orson Welles to serve as narrator. Mostly, though? Meh.

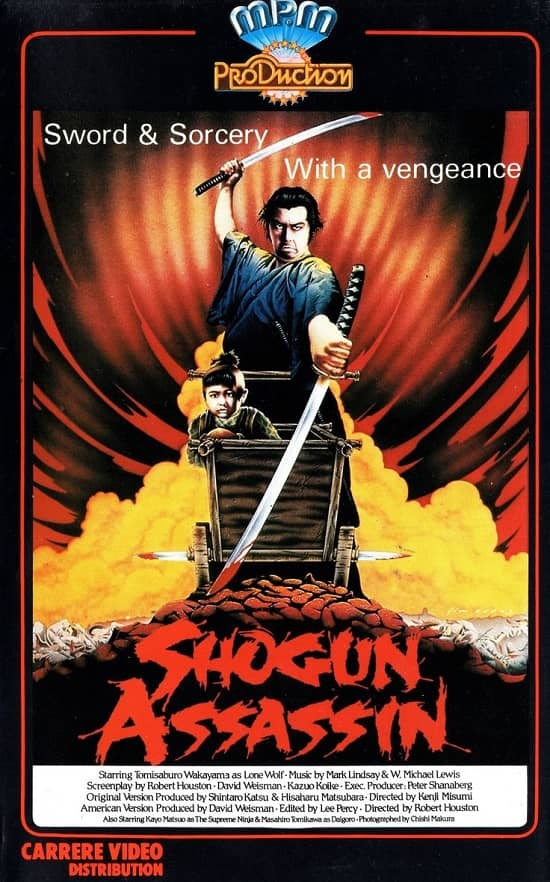

Shogun Assassin

Rating: ***

Origin: Japan/USA 1980

Director: Kenji Misumi/Robert Houston

Source: Criterion Blu-ray

In the Seventies, the Lone Wolf and Cub movies (1972-74) were almost entirely unknown outside of Asia, deemed too violent for the American and European markets. In 1980, producer David Weisman paid Toho studios $50,000 for the American rights to the films, and his partner, avant-garde filmmaker Robert Houston, recut the first two Lone Wolf movies into Shogun Assassin, dubbing the dialogue with an entirely new script by Houston and Weisman. The result used part of the origin story from the first movie in the Lone Wolf series, Sword of Vengeance, and nearly all of the second, Baby Cart at the River Styx. Beyond just editing the two original films together, the new movie’s story was significantly altered, simplifying the plot to cut out nearly all the period politics and reducing it to a duel between the assassin Lone Wolf (Tomisaburo Wakayama) and Lord Retsudo of the Yagyu Clan (Yunosuke Ito), here renamed the Shogun. Why that latter simplification? 1980 was the year of the hugely successful Shogun TV mini-series, which introduced mass American audiences to samurai history, so Shogun was a magic word to conjure with.

More than that, Houston and Weisman gave their version a narrative voiceover by Lone Wolf’s three-year-old son Daigoro, in which the toddler explains his father’s milieu of sudden death, calmly keeping a count, for example, of the hundreds of the “Shogun’s ninja” that the Lone Wolf has slain. It’s a daring move, edgy and hilarious, and it works, elevating Shogun Assassin from a mere violent exploitation flick into a cult classic. Moreover, Houston’s re-editing is sharp, the dubbing, often deliberately humorous, is clever and well done, and the film has a cheesy but tense soundtrack by Mark Lindsay, the former lead singer of Paul Revere & the Raiders.

The film was released to the American grindhouse circuit in 1980, where it was an instant niche success, becoming a notorious gotta-see-it violent video in America and Europe during the VHS years of the early Eighties, molding the tastes and ambitions of later directors such as Quentin Tarantino and Robert Rodriguez. Even today, Shogun Assassin holds up as sheer entertainment — and if it gets the viewer to take a look at the outstanding original films it was adapted from, that alone justifies its existence.

Kagemusha

Rating: *****

Origin: Japan, 1980

Director: Akira Kurosawa

Source: Criterion DVD

“Kagemusha” means shadow warrior, an apt name for a film about seeming, about the pretense of reality and how it can come to seem real, though it is not. In 1573, late in the Warring States period, a petty thief (Tatsuya Nakadai), so unimportant he’s never even named, is saved from execution by Lord Nobukado (Tsutomu Yamazaki) because of his uncanny resemblance to Nobukado’s elder brother, the daimyo Takeda Shingen (also Tatsuya Nakadai). Nobukado thinks the thief might be useful as a double for his brother. Shingen, a great general in an age of great generals, dreams of marching on the capital of Kyoto and declaring himself military ruler of Japan, but he is blocked by the alliance of Oda Nobunaga (Daisuke Ryu) and Tokugawa Ieyasu (Masayuki Yui), two other daimyo with brilliant strategic minds.

At a siege of one of Ieyasu’s castles, Shingen is shot by a sniper and badly wounded, though the extent of his injury is covered up. Shingen and Nobukado decide to deploy the double to cover for the wounded clan lord until he can recover — but then Shingen dies, a fact that is hidden from everyone, even the thief. According to Shingen’s last wishes, his death is to be concealed for three years so the Takeda clan’s enemies can’t take advantage of the loss of their greatest general.

The thief starts to enjoy his new role, but when he falls from Shingen’s horse and his imposture is nearly discovered, he decides he’s had enough and plans to rob Shingen’s castle and escape. In the treasure room he finds a great jar, and, thinking it must contain something valuable, he stealthily cracks it open, only to be struck down in terror when he finds his own face staring back at him from Shingen’s pickled corpse. Disgusted with the thief, the Takeda officers decide to give up on the deception and send him away. But when the thief realizes what the dead daimyo really meant to his people, he begs the officers for another chance. Over time, the double grows into his role, learns to love Shingen’s young grandson, and almost forgets that he’s nothing more than an imitation. But when he has to seem to lead the Takeda army during a frightening night battle, and sees Shingen’s retainers give their own lives to protect the life of their dead lord’s double, the reality of his false position is brought home to him.

Though there’s a lot of warfare here, many battles beautifully staged, this is not a samurai action movie, so don’t expect Yojimbo or The Seven Samurai. This is a superbly acted period drama stunningly depicted with Kurosawa’s consummate visual poetry. Though it was the most successful Japanese movie of 1980, the director had a long, hard road to get it made, finally having to turn to fans George Lucas and Francis Ford Coppola to find extra American money to fund it. There were other problems: Kurosawa had written the dual lead role for star Shintaro Katsu, best known for his Zatoichi series, but Katsu and Kurosawa clashed on the first day of shooting and Katsu either quit or was fired, depending on who you ask. Kurosawa finally settled on Tatsuya Nakadai to fill the part, and it was the right choice — his moving performance is one you won’t soon forget.

Where can I watch these movies? I’m glad you asked! Many movies and TV shows are available on disk in DVD or Blu-ray formats, but nowadays we live in a new world of streaming services, more every month it seems. However, it can be hard to find what content will stream in your location, since the market is evolving and global services are a patchwork quilt of rights and availability. I recommend JustWatch.com, a search engine that scans streaming services to find the title of your choice. Give it a try. And if you have a better alternative, let us know.

Previous installments in the Cinema of Swords include:

Lone Wolf and Cub, Part I

Premium Peplum

The Book Was Better

Shogunate’s End

Peak Musketeers

Lone Wolf and Cub, Part 2

Arthur, King of the Britons

Sinbads Three

Premium Peplum: Top Hercs

Fight Direction by William Hobbs

Mash-Up or Shut Up

Classics on Screen — 1977

Wuxia in the Time of Kung Fu

So Many Prisoners of Zenda

Seventies Hall of Shame

LAWRENCE ELLSWORTH is deep in his current mega-project, editing and translating new, contemporary English editions of all the works in Alexandre Dumas’s Musketeers Cycle, with the fifth volume, Between Two Kings, coming in July from Pegasus Books in the US and UK. His website is Swashbucklingadventure.net.

Ellsworth’s secret identity is game designer LAWRENCE SCHICK, who’s been designing role-playing games since the 1970s. He now lives in Dublin, Ireland, where he’s writing Dungeons & Dragons scenarios for Larian Studios’ Baldur’s Gate 3.

Another Ellsworth’s Cinema of Swords? Sure, Shogun!

Is it wrong for me to admit that I enjoyed Shogun Assassin the most of all three films?

They are all worth seeing at least once though.

Thank you, Mr. Ellsworth!

Great article as usual from you, Sir! I have to agree that although I had watched and enjoyed Shogun and some of Kurosawa’s Samurai films (loved Seven Samurai and Sanjuro), it was Shogun’s Assassin that really turned me into a Chambara film freak. I used to use it as the gateway drug for my friends to get them interested in Chambara films.