Fantasia 2021, Part LXXII: Final Thoughts

I saw more movies at Fantasia 2021 than at any previous iteration of the festival. By my count, I watched 96 short films from 25 countries and 69 features from 19 countries, with a total of 32 different countries represented in my viewing this year. The quality was there, too. I don’t have any metric to track these things, but it felt like both the number of exceptional films and the overall quality of the movies in 2021 was higher than in the past.

I saw more movies at Fantasia 2021 than at any previous iteration of the festival. By my count, I watched 96 short films from 25 countries and 69 features from 19 countries, with a total of 32 different countries represented in my viewing this year. The quality was there, too. I don’t have any metric to track these things, but it felt like both the number of exceptional films and the overall quality of the movies in 2021 was higher than in the past.

Before going on with a look back at this year’s Fantasia experience, I want to thank, as every year, Fantasia’s organisers and programmers and volunteers, and generally everyone involved with the festival. It is always in many ways the highlight of my year. I also want to thank John O’Neill for hosting these reviews here, and for keeping Black Gate up and running. And I want to thank everyone who takes the time to read and comment. Fatigue issues have tended to keep me from replying here as much as I’d like, but every comment is noted and valued.

The Fantasia experience this year was similar to last year’s; there was just more of it. There was a notable improvement in the way scheduled movies played — last year you had to start watching within five or ten minutes of the scheduled start time, while this year the films were available for a three-hour window beginning at a given time. That made things a lot easier, and the fact that almost all of them were also available for 24 hours two days after their first showing helped a lot as well.

I note that this was the least social Fantasia’s ever been for me. Some of that’s personal choice; last year the Festival had a Discord server, which I liked and used, while this year they did things through Gather Town, which for a variety of reasons I didn’t care for. At any rate, I do miss the interaction with other writers at Fantasia, and of course the live audiences. Still, the festival’s adapted as well as possible to the virtual format, I think, with good use of their YouTube channel. And it must be said: whatever loss I’ve had in not seeing the films in theatres pales next to the gain I have of being able to see them at all — and especially the psychological gain of being transported away from the reality of the pandemic by the unpredictable visions of these films.

This is the second year the festival’s gone ahead despite COVID, and this year had the sense of scale of a full Fantasia; last year’s two-week iteration was a wonderful relief from pandemic stress, but 2021 was back to a full three weeks and felt to me as though it had the range and variety of most Fantasias. That’s despite film production being halted or hindered for long stretches of the past couple of years. I noticed that in the question-and-answer sessions a lot of filmmakers mentioned that they’d finished or almost finished their principal photography just as COVID really hit the part of the world they were filming in. Then they ended up with more post-production time than they’d anticipated, as theatres were shut down. So these are mostly movies made pre-COVID; we’ll see how the pandemic shapes what plays at the festival in future years.

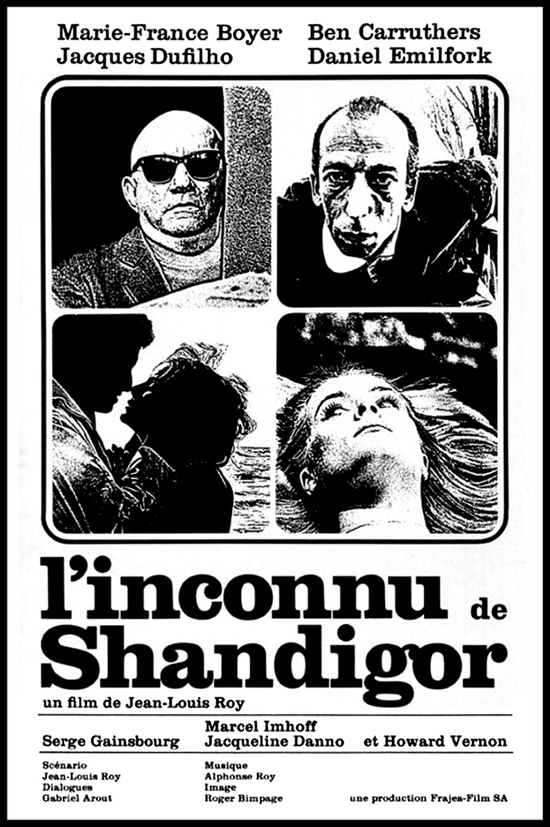

It’s tempting to wonder whether, if these films feel stronger than most years, extra time in the editing room helped them. One way or another, I was struck by the number of good-to-excellent films I got to see, whether from North America or around the world. And, as is often the case at Fantasia, I was struck by the older films that have been given revivals — Tombs Of the Blind Dead is relatively well-known, Mill Of the Stone Women maybe less so, and The Unknown Man of Shandigor hardly remembered. And all of them good movies.

It’s tempting to wonder whether, if these films feel stronger than most years, extra time in the editing room helped them. One way or another, I was struck by the number of good-to-excellent films I got to see, whether from North America or around the world. And, as is often the case at Fantasia, I was struck by the older films that have been given revivals — Tombs Of the Blind Dead is relatively well-known, Mill Of the Stone Women maybe less so, and The Unknown Man of Shandigor hardly remembered. And all of them good movies.

That these works get high-quality restoration may be a sign of the times. In my wrap-up piece for Fantasia 2017 I made the point that we’re living in a golden age of genre film, with great fantasy and horror and science-fiction and crime films coming from all around the world, and most of them available to the average consumer. That’s only gotten truer over the last few years. As I said then, there are big-budget franchise films, and major arthouse films that use genre elements, and lower-budget independent films, and all of these things coming from more and more countries. But to this I’ll now add that the interest is there in great work from the past; so we get the restoration of classic genre films. And there’s also the broad critical interest in genre and genre history for major documentaries like Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror, which has already become the centrepiece for a box set of classic films.

It turns out that a golden age of genre film doesn’t just mean great films. It also has spin-off effects. In fact we’re at the point where it’s difficult to follow all the genre film out there, particularly if you include TV (and there are filmmakers, like David Lynch and Mike Flanagan, who move back and forth). One can argue about the merits of Netflix and other streaming services and what they’re doing to the film industry, but at the very least they’re producing an incredible volume of content.

It turns out that a golden age of genre film doesn’t just mean great films. It also has spin-off effects. In fact we’re at the point where it’s difficult to follow all the genre film out there, particularly if you include TV (and there are filmmakers, like David Lynch and Mike Flanagan, who move back and forth). One can argue about the merits of Netflix and other streaming services and what they’re doing to the film industry, but at the very least they’re producing an incredible volume of content.

Mostly, of course, that’s good. Every golden age needs not just top-of-the-line masterpieces but also a deep bench of fascinating stuff, a critical mass that keeps you coming back to watch more because you don’t know what you’re going to get. Most of my life I’ve heard about how the early-to-mid 1970s were a golden age for (mostly realist) American films, but I never really understood that until I got the Criterion Channel and saw not just the famous highly-praised films of the time but the very good things that were released around them — just in the last week or two I saw Across 110th Street, a 1972 crime movie set in Harlem, and The Panic in Needle Park, a 1971 film about heroin addicts in New York City, and both of them were excellent in a very specifically early-70s gritty-realist way. That’s what it means to have a golden age, I think; having a wealth of material out there to be explored.

And so despite COVID there’s still a flood of genre films coming out, and a plethora of streaming services to watch them on. Film’s a technologically-shaped medium, and the technology of watching film continues to evolve; but it’s generally becoming easier to get more fantasy effects into lower-budget films. And it turns out that if you can put anything you want on film and make it move, a lot of creators want to put genre imagery in motion. But it also turns out that a lot of creators enjoy structuring stories around fantastical ideas, whether there are fantastic visuals or not. The golden age doesn’t look to be ending any time soon. It’s survived a global pandemic. Who can tell where we’ll go from here? All I can say is that I hope to be at Fantasia, next year and in the years to come, watching cinematic visions playing out on whatever screen they find.

And so despite COVID there’s still a flood of genre films coming out, and a plethora of streaming services to watch them on. Film’s a technologically-shaped medium, and the technology of watching film continues to evolve; but it’s generally becoming easier to get more fantasy effects into lower-budget films. And it turns out that if you can put anything you want on film and make it move, a lot of creators want to put genre imagery in motion. But it also turns out that a lot of creators enjoy structuring stories around fantastical ideas, whether there are fantastic visuals or not. The golden age doesn’t look to be ending any time soon. It’s survived a global pandemic. Who can tell where we’ll go from here? All I can say is that I hope to be at Fantasia, next year and in the years to come, watching cinematic visions playing out on whatever screen they find.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.