Fantasia 2021, Part LXXI: Woodlands Dark And Days Bewitched: A History Of Folk Horror

When I first saw the schedule for Fantasia 2021, none of the films playing the final night of the festival struck me as something I wanted to review here. I therefore decided I’d pick one of the movies available on-demand throughout Fantasia as my personal closing film. Which then raised the question of which of those movies felt like enough of an event to mark the end of a three-week revel in the weirdness of genre cinema. And the answer to this question was clear at once. My big finish for Fantasia 2021 would be the three-hour-plus documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror.

When I first saw the schedule for Fantasia 2021, none of the films playing the final night of the festival struck me as something I wanted to review here. I therefore decided I’d pick one of the movies available on-demand throughout Fantasia as my personal closing film. Which then raised the question of which of those movies felt like enough of an event to mark the end of a three-week revel in the weirdness of genre cinema. And the answer to this question was clear at once. My big finish for Fantasia 2021 would be the three-hour-plus documentary Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror.

Right beforehand I watched the short bundled with it. “Saudade” is a 20-minute film from Singapore written and directed by Russell Morton, presenting stories and rituals of the Kristang people, a community of mixed Eurasian ancestry that arose in the area of Malacca four or five hundred years ago. The film, in the Kristang language, is structured around three sequences. The first is a folk dance, the second’s a conversation between a fisherman and his wife about stories and the shrimp that have vanished from the seas, and the third is a meeting with a mythic entity called the Oily Man — a human who sold his soul to the Devil. The film’s very concerned with ghosts and the survival of stories; the title’s a Portuguese word that refers to a kind of melancholic nostalgia for a desired thing that will not come again, and there seems a connection there with the film’s interest in history and culture. The movie’s photographed well, with a colourful shot at the end reminiscent of a dance of death, and it’s evocative, though the connections are elliptical to me. That may be deliberate, as I’m not sure whether the movie’s meant to present the Kristang culture to others, to speak to the Kristang people, or to record some pieces of Kristang culture. Or all of the foregoing. Either way, there’s a tone of longing and distance here that, so far as I can tell, bears out the promise of the title.

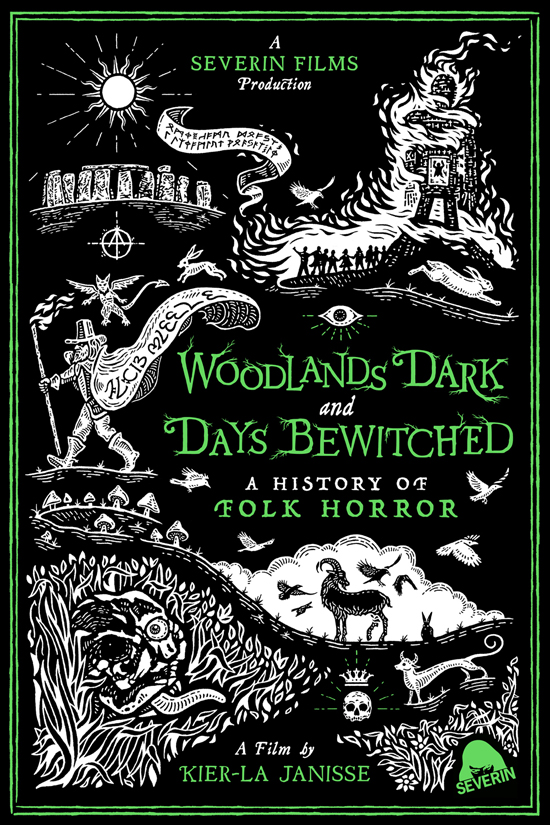

Woodlands Dark and Days Bewitched: A History of Folk Horror is directed by Kier-la Janisse, the founder of The Miskatonic Institute of Horror Studies. Janisse has written several books on horror, and her micropress Spectacular Optical has published several more (including Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin). Woodlands Dark is her first feature, and it has more than 50 interviewees discussing folk horror films from around the world. It’s coming on blu-ray from Severin Films on December 7, available on its own or as part of a 15-disc collection called ‘All the Haunts Be Ours’ which includes 20 of the movies mentioned in the documentary.

Woodlands Dark tracks the origin of the term ‘folk horror’ back to at least 1936. But the phrase really caught on as a term for a specific genre of horror film following its use in the 2010 TV documentary A History of Horror, referring to films in the vein of the ‘unholy trinity’ of Blood On Satan’s Claw (a 1971 film whose director, Piers Haggard, used the expression in talking about his movie), Witchfinder General (1968), and The Wicker Man (1973). But it’s increasingly used in a larger sense, to include horror films dealing with folk traditions of countries far beyond the UK. Woodlands Dark opts for the more expansive definition — it spends over an hour discussing UK folk horror, but the majority of the documentary considers examples from around the world, ultimately at least touching on over 200 films and the occasional TV show.

Woodlands Dark tracks the origin of the term ‘folk horror’ back to at least 1936. But the phrase really caught on as a term for a specific genre of horror film following its use in the 2010 TV documentary A History of Horror, referring to films in the vein of the ‘unholy trinity’ of Blood On Satan’s Claw (a 1971 film whose director, Piers Haggard, used the expression in talking about his movie), Witchfinder General (1968), and The Wicker Man (1973). But it’s increasingly used in a larger sense, to include horror films dealing with folk traditions of countries far beyond the UK. Woodlands Dark opts for the more expansive definition — it spends over an hour discussing UK folk horror, but the majority of the documentary considers examples from around the world, ultimately at least touching on over 200 films and the occasional TV show.

Interviews with a wide range of critics and filmmakers are focussed and intelligent; occasionally Janisse appears herself speaking in the same format as other critics. Clips from films under discussion are frequent, and often spectacularly well-chosen. The six chapters of the film are divided by animated collage sequences from maverick filmmaker Guy Maddin, and the soundtrack features renditions of traditional folk songs. It makes for a coherent, perceptive, and deeply well-informed whole.

The movie doesn’t try to present a simple definition of folk horror, instead looking at various films critics suggest are relevant to the idea of ‘folk horror’ and seeing what emerges. It also doesn’t try to tell a chronological ‘story’ about the development of the genre. There are chapters considering the roots of the British folk horror tradition, and how it tied into the emergence of neo-paganism in the 70s, and (the final chapter) a look at manifestations of folk horror in present-day film. But it doesn’t go decade-by-decade, much less year-by-year. This means the movie doesn’t consider the way one film might have influenced another, but also means that it’s not trying to establish a single genealogy or coherent tradition. Folk horror, in this presentation, is an impulse that has arisen in many different places in many different ways, and all of those ways are relevant to what Woodlands Dark is exploring.

The movie doesn’t try to present a simple definition of folk horror, instead looking at various films critics suggest are relevant to the idea of ‘folk horror’ and seeing what emerges. It also doesn’t try to tell a chronological ‘story’ about the development of the genre. There are chapters considering the roots of the British folk horror tradition, and how it tied into the emergence of neo-paganism in the 70s, and (the final chapter) a look at manifestations of folk horror in present-day film. But it doesn’t go decade-by-decade, much less year-by-year. This means the movie doesn’t consider the way one film might have influenced another, but also means that it’s not trying to establish a single genealogy or coherent tradition. Folk horror, in this presentation, is an impulse that has arisen in many different places in many different ways, and all of those ways are relevant to what Woodlands Dark is exploring.

From this perspective, many aspects of folk horror can be seen. The movie notes the tendency in folk horror to juxtapose the prosaic and the uncanny; its themes of ritual and collective storytelling; its depictions of folk cultures surviving in spite of dominant cultures; how it presents material that is outside of modernity; its tendency to dramatise the return of the repressed. And all of this in the first few minutes, before Chapter One begins.

Generally, the documentary’s less concerned with cinematic technique or the effect an individual movie has on viewers than with the themes common to folk horror in general. For Janisse, folk horror is engaged with history and the way we conceptualise our history; a ‘folk’ is not something outside of historical development, but something culturally situated within time. There is a tension, the film argues, between the past and the present that is mediated in folk horror. The genre is a way to process social change, contrasting eras, and it is this that links the different manifestations of folk horror around the world. Folk horror also talks about hierarchy, if only local hierarchy, and so about power structures: about the situations of aristocrats and of peasants. If the idea of ‘folk horror’ as a genre was first articulated in the UK, with UK films as the core texts, does this say more about folk horror or about the UK?

Generally, the documentary’s less concerned with cinematic technique or the effect an individual movie has on viewers than with the themes common to folk horror in general. For Janisse, folk horror is engaged with history and the way we conceptualise our history; a ‘folk’ is not something outside of historical development, but something culturally situated within time. There is a tension, the film argues, between the past and the present that is mediated in folk horror. The genre is a way to process social change, contrasting eras, and it is this that links the different manifestations of folk horror around the world. Folk horror also talks about hierarchy, if only local hierarchy, and so about power structures: about the situations of aristocrats and of peasants. If the idea of ‘folk horror’ as a genre was first articulated in the UK, with UK films as the core texts, does this say more about folk horror or about the UK?

Then again, the documentary also suggests that the genre has to do with landscape and even with psychogeography, the perceived mental impression of history on land; this is a movie that can move on a dime from a reference to novelist Peter Ackroyd to a discussion of Quatermass And the Pit. Geraldine Beskin, lecturer and occult store owner, suggests that the Industrial Revolution represents a key break with folk traditions, here as in so many other ways. Folk horror then forcibly returns an older way of imagining the land to our consciousness, and something in that is terrifying.

Folk horror is a sufficiently capacious subject that even in a film this long, there have to boundaries drawn and omissions made. After three chapters on the UK the third chapter of the movie covers American folk horror, and while the film does a good job of acknowledging that the US (even more so than Britain) breaks down into different kinds of regional and cultural types of folk horror, it has less time to cover its subject and so must leave out films that might have been useful to consider in this context — Twin Peaks, Night of the Hunter, and The Blair Witch Project being examples that spring to mind. The fifth chapter, the longest of the documentary, touches on movies from all around the world, and inevitably different viewers will find gaps, whether that’s films not mentioned, or countries (like Canada), or whole continents (I noted nothing mentioned from Africa).

Folk horror is a sufficiently capacious subject that even in a film this long, there have to boundaries drawn and omissions made. After three chapters on the UK the third chapter of the movie covers American folk horror, and while the film does a good job of acknowledging that the US (even more so than Britain) breaks down into different kinds of regional and cultural types of folk horror, it has less time to cover its subject and so must leave out films that might have been useful to consider in this context — Twin Peaks, Night of the Hunter, and The Blair Witch Project being examples that spring to mind. The fifth chapter, the longest of the documentary, touches on movies from all around the world, and inevitably different viewers will find gaps, whether that’s films not mentioned, or countries (like Canada), or whole continents (I noted nothing mentioned from Africa).

But then, it may be less important for Woodlands Dark to be encyclopedic than for it to bring out the most important themes of folk horror. And it certainly does that. Occasionally it brings up points that feel as though they could have been more deeply explored — romantic nationalism, say, or the influence of theosophy on horror. But in fact these are things that past a certain point pull one away from the genre. The documentary does a strong job of establishing boundaries for its subject, not least by mostly restricting itself to film; an early chapter discusses the impact on British folk horror cinema of prose writers like M.R. James, as well as lesser-known writers like Eleanor Scott and Grant Allen, but in general the documentary sticks with the manifestation of folk horror in film. So a writer like Alan Garner becomes a sort of subterranean influence, through the adaptation of The Owl Service and Red Shift into TV shows in the 70s.

I wonder whether there will be a kind of quantum effect with the documentary, in which its skillful articulation of its theme and concept will end up influencing the genre it describes. There is a magisterial feel to it, not because it excludes other perspectives, but because of its easy intelligence and thorough knowledge of its subject. Certainly it’s talking about something that has a growing constituency. Artists and audiences are both fascinated by folk horror, and the last chapter of the film talks about the efflorescence of the genre in contemporary film — particularly in the success of Midsommar, but also in the form of movies like November and even The Creeping Garden. Woodlands Dark points out that the genre flourished in the UK in the 70s, a time of pessimism about the future; and if it is flourishing now, perhaps it’s because a similar pessimism is also widespread.

I wonder whether there will be a kind of quantum effect with the documentary, in which its skillful articulation of its theme and concept will end up influencing the genre it describes. There is a magisterial feel to it, not because it excludes other perspectives, but because of its easy intelligence and thorough knowledge of its subject. Certainly it’s talking about something that has a growing constituency. Artists and audiences are both fascinated by folk horror, and the last chapter of the film talks about the efflorescence of the genre in contemporary film — particularly in the success of Midsommar, but also in the form of movies like November and even The Creeping Garden. Woodlands Dark points out that the genre flourished in the UK in the 70s, a time of pessimism about the future; and if it is flourishing now, perhaps it’s because a similar pessimism is also widespread.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

The Severin people are great.