Fantasia 2021, Part LXX: The Unknown Man of Shandigor

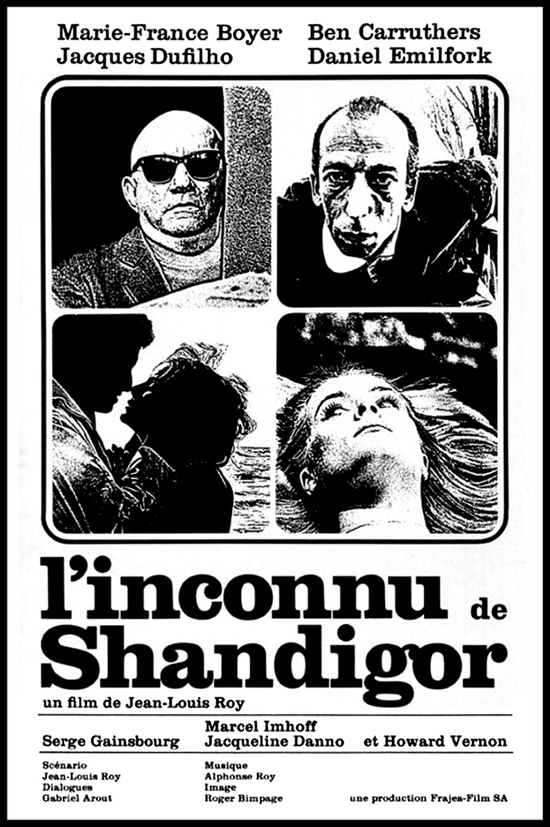

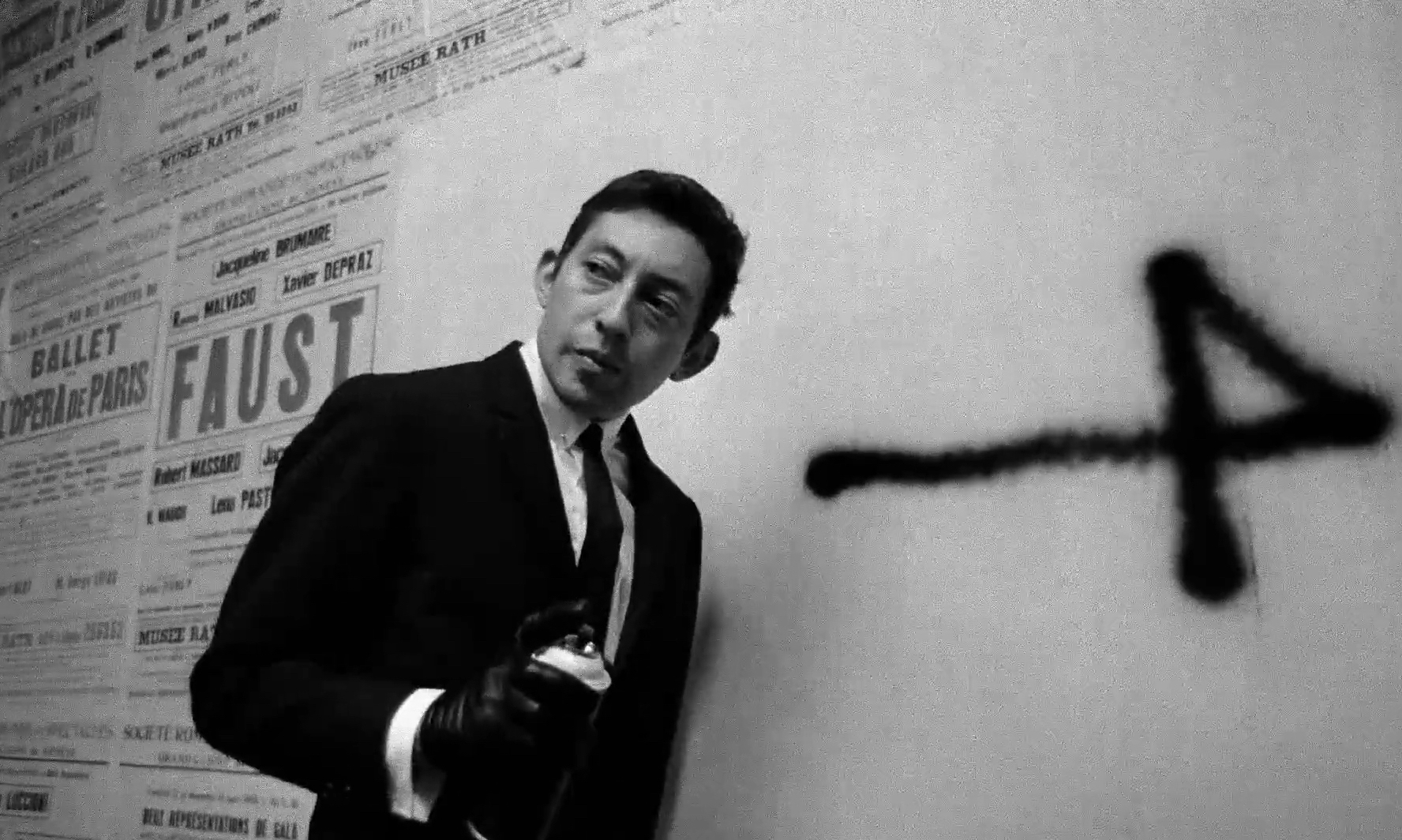

In the waning hours of the 2021 Fantasia Film Festival I sat down to watch The Unknown Man of Shandigor (L’inconnu de Shandigor), a 1967 Swiss spy film directed by Jean-Louis Roy, who collaborated on the script with Gabriel Arout and Pierre Koralnik. The film’s got a new 4K restoration by the Cinematheque Suisse; I’d never heard of the movie, but the description was intriguing, a black-and-white mod odyssey through the weirdness of the 1960s, with nods to Dr. Strangelove and Alphaville, and including Serge Gainsbourg as the leader of a group of bald turtleneck-clad assassins. Was this a lost classic, or an eccentric curiosity? Or both?

In the waning hours of the 2021 Fantasia Film Festival I sat down to watch The Unknown Man of Shandigor (L’inconnu de Shandigor), a 1967 Swiss spy film directed by Jean-Louis Roy, who collaborated on the script with Gabriel Arout and Pierre Koralnik. The film’s got a new 4K restoration by the Cinematheque Suisse; I’d never heard of the movie, but the description was intriguing, a black-and-white mod odyssey through the weirdness of the 1960s, with nods to Dr. Strangelove and Alphaville, and including Serge Gainsbourg as the leader of a group of bald turtleneck-clad assassins. Was this a lost classic, or an eccentric curiosity? Or both?

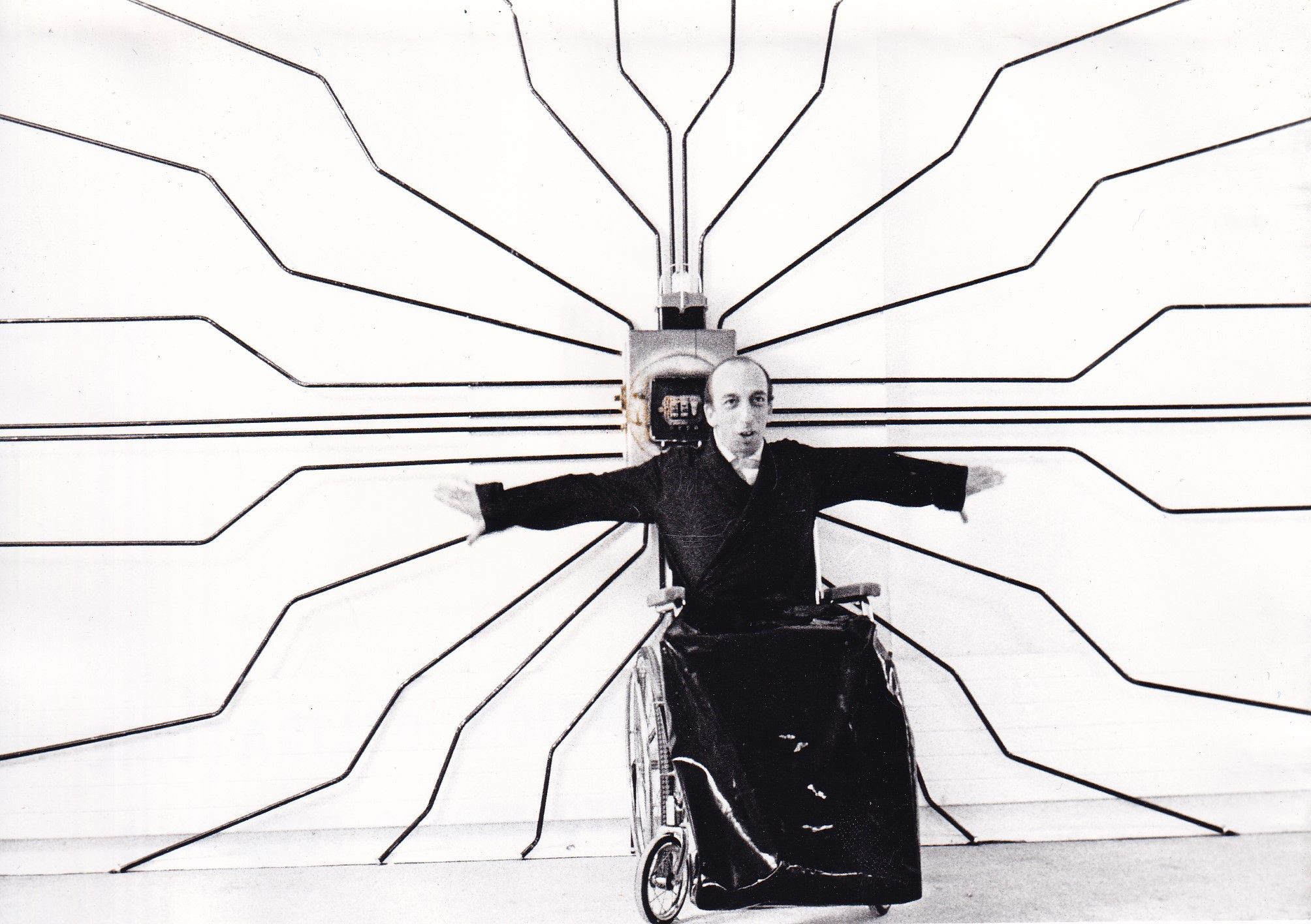

The plot of the film concerns one Doctor Von Krantz (Daniel Emilfork, who would go on to feature in The City of Lost Children), an admirer of Dracula prone to observations such as: “I don’t like humanity. Or, I do, but in a jar of arsenic.” The good doctor has invented the Canceler (or Annulator), which can nullify a nuclear explosion. As this is the height of the Cold War, his fortified home has now become the target for spies from multiple different nations. American agent Bobby Gun (Howard Vernon) races with the dastardly Russian Shostakovich (Jacques Dufilho) to get their hands on the device — but the key may lie with Von Krantz’s young and idealistic daughter Sylvaine (Marie-France Boyer), who dreams of a man she once knew (Ben Carruthers), a mysterious man in the city of Shandigor.

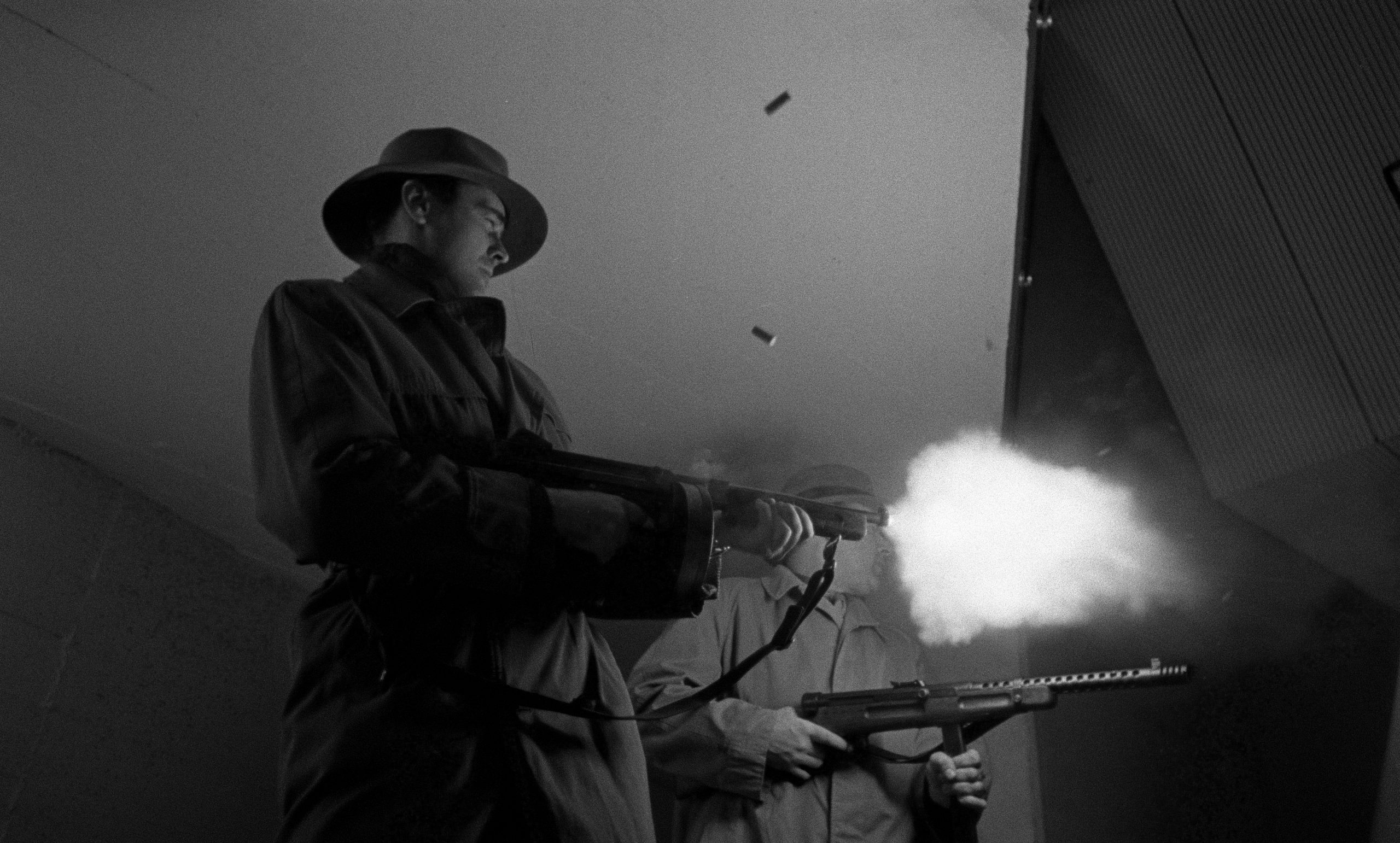

The visuals here are lovely, high-contrast black-and-white with surreal touches throughout. 1960s black-and-white films often have an incredible precision to their photography; some of the best-looking monochrome movies were made just as colour was taking over. So Shandigor has the dramatic look of something like In Cold Blood with the oddity of Seconds, and like that film explores weird compositions and surreal imagery.

The visuals here are lovely, high-contrast black-and-white with surreal touches throughout. 1960s black-and-white films often have an incredible precision to their photography; some of the best-looking monochrome movies were made just as colour was taking over. So Shandigor has the dramatic look of something like In Cold Blood with the oddity of Seconds, and like that film explores weird compositions and surreal imagery.

Tonally, there’s an intriguing mix of genres and influences. You can see echoes of a lot of things here: Strangelove and Alphaville, but also the Steed-and-Mrs-Peel Avengers, Modesty Blaise, maybe Diabolik — all those surreal 1960s spy stories, more tongue-in-cheek than the Bond films but not as parodic as, say, Our Man Flint or The President’s Analyst. Put another way, things weirder than The Man From U.N.C.L.E., but not slapstick like Get Smart. It’s a surprisingly well-populated subgenre, which perhaps speaks to the mentality of the times. These stories don’t have the outright psychedelia that was spreading through society at about the time Shandigor was released, but present a kind of dreamlike twist on Cold War narratives and expectations. Maybe it’s best to say that like many of them Shandigor is a mod film, Revolver and not Sergeant Pepper’s.

It’s more of a comedy-satire than a straight spy film, but only just; there is a straightforward narrative that works on its own terms. It’s straight-faced, but the plot is shaped by ludicrous elements, as are the performances. The spies, generally, are more direct parodies of the Cold War tension, and one of the jarring aspects of the film is how the actors are in different registers — Vernon plays Bobby Gun with a straight face but knowingly sends up the image of the bitter overexperienced superspy, while Dufilho leans into the scenery-chewing aspect of the Russian villain Shostakovich. And yet the overall tone of surrealism means none of it’s out of place.

It’s more of a comedy-satire than a straight spy film, but only just; there is a straightforward narrative that works on its own terms. It’s straight-faced, but the plot is shaped by ludicrous elements, as are the performances. The spies, generally, are more direct parodies of the Cold War tension, and one of the jarring aspects of the film is how the actors are in different registers — Vernon plays Bobby Gun with a straight face but knowingly sends up the image of the bitter overexperienced superspy, while Dufilho leans into the scenery-chewing aspect of the Russian villain Shostakovich. And yet the overall tone of surrealism means none of it’s out of place.

In fact there’s an intriguing mix of genres at work here, genres which don’t quite blend homogenously, and so make for the movie’s unique sensibility. The science-fictional premise sets up an espionage-movie infrastructure, but the beautiful daughter of the mad scientist pining for her lost lover is straight out of gothic romance. Said mad scientist also keeps a carnivorous aquatic Thing in his pool, and so we have moments of horror fiction.

This could have been a problem. Given the range of tones and genres and images, this film should be an ungodly mess. But it isn’t. It’s unpredictable, yes, with a major new faction of spies introduced well past the halfway mark. But it holds together. There’s a sensibility that binds the disparate matter of the film into a coherent whole.

This could have been a problem. Given the range of tones and genres and images, this film should be an ungodly mess. But it isn’t. It’s unpredictable, yes, with a major new faction of spies introduced well past the halfway mark. But it holds together. There’s a sensibility that binds the disparate matter of the film into a coherent whole.

Some of that is simply the visual weirdness. The dream-city of Shandigor (played by the architecture of Antoni Gaudí). The group of five bald lookalike assassins, moving in sync. Objects dramatically in the foreground of shots. Camera angles shot from high above or below. There’s a vocabulary reminiscent of old comic books that lends the material some kind of unity.

There’s also a unity that comes from the sense of period. This is not a movie that could have been made at any other time than the late 1960s. It’s got too much to do with the Cold War; it’s a movie concerned with its time — and at the same time seems to want to stand outside that time, as though it’s looking for some new form. There’s a desire to pull in bits and pieces of everything, to cycle through genre after genre to play about with their imagery, and then to use that pop sensibility in some new way. It’s not quite pastiche, because there’s too much original here. Satire’s a part of it, a knowingness, but it’s not quite camp as I think of it. As I read the movie, it’s ridiculing spies and the morality of spy stories, but also is fascinated with the visual power of the genre and its emotional beats.

There’s also a unity that comes from the sense of period. This is not a movie that could have been made at any other time than the late 1960s. It’s got too much to do with the Cold War; it’s a movie concerned with its time — and at the same time seems to want to stand outside that time, as though it’s looking for some new form. There’s a desire to pull in bits and pieces of everything, to cycle through genre after genre to play about with their imagery, and then to use that pop sensibility in some new way. It’s not quite pastiche, because there’s too much original here. Satire’s a part of it, a knowingness, but it’s not quite camp as I think of it. As I read the movie, it’s ridiculing spies and the morality of spy stories, but also is fascinated with the visual power of the genre and its emotional beats.

I note that the characters aren’t defined in any realist way, but some of them have at least a kind of dreamlike life. Still, it’s difficult to imagine watching the movie and caring deeply about what happens to the characters; difficult to imagine viewers identifying with these characters in any profound way. They’re interesting enough to follow, even the flattest and most obviously satirical, but there’s a kind of postmodernist detachment to the movie. It’s a visual experience, it’s unpredictable, it’s inventive, but it’s mainly a glossy surface.

I suspect that part of the reason Shandigor didn’t have more success when it was released was because of that lack of easily sympathetic characters. There’s not really a gain to offset the loss; it’s experimental in a very 1960s way, but there were other films that were doing similar things. Still, the sheer level of invention in this film ought to have drawn more notice. And there are some genuine pulp thrills in the unfolding of the story. The film’s worth the work put into restoring it, and I hope the new version leads to its rediscovery and re-evaluation. It may not be a lost classic, but it’s far more than a curiosity.

I suspect that part of the reason Shandigor didn’t have more success when it was released was because of that lack of easily sympathetic characters. There’s not really a gain to offset the loss; it’s experimental in a very 1960s way, but there were other films that were doing similar things. Still, the sheer level of invention in this film ought to have drawn more notice. And there are some genuine pulp thrills in the unfolding of the story. The film’s worth the work put into restoring it, and I hope the new version leads to its rediscovery and re-evaluation. It may not be a lost classic, but it’s far more than a curiosity.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Looks like this is only available in French, with no subtitles in any language. No listing of new or old versions at the usual online sites (Amazon, eBay), used or new. I did check it out on Cinematheque Suisse, but it’s part of a 3-disc package (which sounds GREAT) but, as I noted, only in French. I’ll keep looking!!