Fantasia 2021, Part LXVIII: Midnight In A Perfect World

“Aquatic Bird” is an 18-minute short film from Chinese writer-director Zhang Nan. It weaves together the stories of three interrelated characters — a prostitute (Bird), a man who admires her from a distance (Aqua), and one of her regular clients. The first two are brought together by the light of a green laser pointer; there is a lot of surrealism in this film. It looks very nice, and the script’s very taut — but given the weirdness of the film, I wonder if maybe a bit too taut. To the extent I was able to follow it, the structure worked and built to a solid conclusion. But there’s a lot I did not understand, notably the use of a dream scene, and a peculiar egg of surprising plot significance.

“Aquatic Bird” is an 18-minute short film from Chinese writer-director Zhang Nan. It weaves together the stories of three interrelated characters — a prostitute (Bird), a man who admires her from a distance (Aqua), and one of her regular clients. The first two are brought together by the light of a green laser pointer; there is a lot of surrealism in this film. It looks very nice, and the script’s very taut — but given the weirdness of the film, I wonder if maybe a bit too taut. To the extent I was able to follow it, the structure worked and built to a solid conclusion. But there’s a lot I did not understand, notably the use of a dream scene, and a peculiar egg of surprising plot significance.

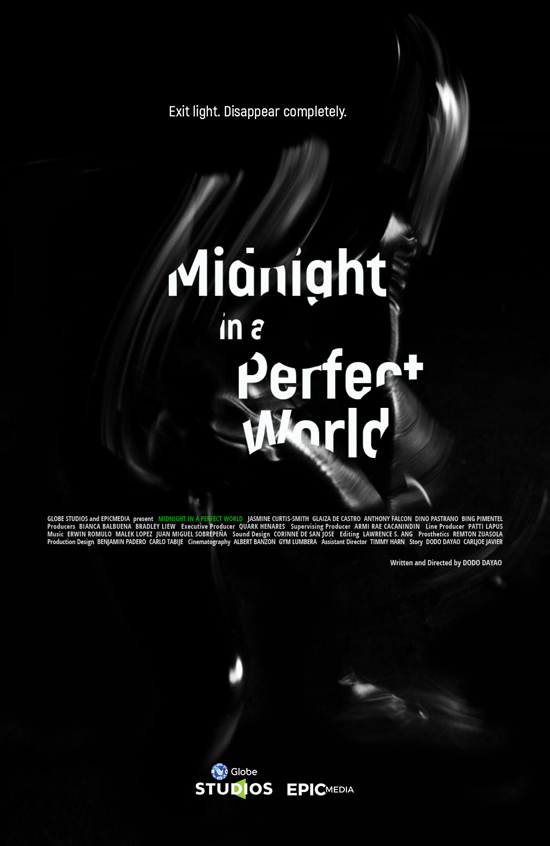

Bundled with it was Midnight In A Perfect World, from the Philippines. Directed by Dodo Dayao, who co-wrote the script with Carljoe Javier, the feature takes place in a near-future Manila where infrastructure’s been upgraded to near-utopian levels. But there are strange blackouts that hit parts of the city after midnight, and you must not be caught out in those places at those times. People disappear, leaving behind only wild rumours about what’s happened to them. Luckily there are safehouses, in which one can take shelter. But there are stories about the dangers of those safehouses, too. The movie follows a group of young friends caught in one blackout, and follow them as they take refuge in a safehouse — then find out one of the group didn’t make it inside.

The first thing to say about this movie is that it captures a striking note of cosmic terror, with a strong inflection of the New Weird (there’s an interesting interview where Dayao mentions being influenced by China Miéville). There are science fiction influences here, certainly, but not in the form of clearly-defined technologies operating in an easily knowable world. Dayao’s said that he worked out the reasons beyond all the unreal elements in the story, but chose not to include them in expository lumps at the expense of breaking up the flow of a scene. In part because of that, the film creates a world which we believe is operating according to rules, however alien, but rules which may be beyond understanding. It’s a little like Lovecraft by way of Laird Barron.

The second thing to note about the movie is that it has an unusual structure. The first act or thereabouts sets up the characters — Mimi (Jasmine Curtis-Smith), Jinka (Glaiza De Castro), Glenn (Anthony Falcon, Ode to Nothing), and Tonichi (Dino Pastrano) — we follow for the rest of the film. And it does this by skipping about in time, showing their relationships and establishing backstory. Some of that backstory is directly relevant to what follows after, notably bits to do with a drug called Magic Star that gives weird visions — the pusher selling it actually uses Philip K. Dick as a point of comparison for the experience. And mixed in with the stories of the main characters are bits to do with a weirdness in the forest beyond the city. But then, just as you think the whole movie’s going to be a jigsaw puzzle, it changes tack.

The second thing to note about the movie is that it has an unusual structure. The first act or thereabouts sets up the characters — Mimi (Jasmine Curtis-Smith), Jinka (Glaiza De Castro), Glenn (Anthony Falcon, Ode to Nothing), and Tonichi (Dino Pastrano) — we follow for the rest of the film. And it does this by skipping about in time, showing their relationships and establishing backstory. Some of that backstory is directly relevant to what follows after, notably bits to do with a drug called Magic Star that gives weird visions — the pusher selling it actually uses Philip K. Dick as a point of comparison for the experience. And mixed in with the stories of the main characters are bits to do with a weirdness in the forest beyond the city. But then, just as you think the whole movie’s going to be a jigsaw puzzle, it changes tack.

Once the film starts following the main characters as they get caught in a blackout and take shelter, or try to, it’s basically linear. Different characters have different plot strands, but there’s nothing unusual in how they’re interlaced. Instead the strangeness of the safehouse becomes a central point. There are no doors into the building; characters remember being about to enter, and then find themselves in a hallway. There are weird sounds from closed-off rooms. There’s a hole in the bathroom with a secret. And there’s a woman (Bing Pimentel) already there who seems to know some things about the place. Dayao’s spoken about the film (in a Fantasia question-and-answer session, among other places) as his take on the haunted house genre. It’s a haunted house movie such as might have been made by David Lynch, but it is definitely that.

Dayao helps establish the house through long takes and deliberate camera moves. There’s a precision to the way the camera travels about the windowless wallpapered corridors of the safehouse, something different from the handheld of characters running about outside. Inside the place or out of it, though, there’s a crepuscular feel, a dimness always about to swallow up the characters, who find themselves having to enter darkened rooms or running through thick night.

Dayao helps establish the house through long takes and deliberate camera moves. There’s a precision to the way the camera travels about the windowless wallpapered corridors of the safehouse, something different from the handheld of characters running about outside. Inside the place or out of it, though, there’s a crepuscular feel, a dimness always about to swallow up the characters, who find themselves having to enter darkened rooms or running through thick night.

There’s a weirdness in the city beyond, too, and it’s even harder to understand. We don’t get to see much of the perfected infrastructure of this future Manila, but we see and hear (over one-sided phone calls) people struggling to make sense of things they see. That struggle to make sense of things is at the core of the film, characters exploring their environment and trying to make it make sense; and characters struggling to sift fact from myth. Ghost stories and urban legends have a part here; they carry partial truths, bits of information among a fog of nonsense. To me, much of the film has to do with questions of truth and perception. There’s a mind-altering drug involved in the story; could the whole thing be a bad trip? Or does the drug actually open one up to some greater truth? If so, how can somebody communicate that truth to someone who’s straight and sober, and how can they understand that chemically altered perception?

I note also that there are direct echoes of politics in the Philippines, past and present. Dayao’s spoken about how he had the Marcos era more on his mind than the Duterte regime, but then he’s also said that he sees the film as fundamentally the story it appears to be — not a coded allegory for politics but a fantasy-horror tale. I certainly don’t know enough to speculate about political parallels. But the way the characters struggle with mysterious powers, with a society that operates by unknown rules, feels like a general observation about people in society; whatever specific points Dayao’s making, it is I think broadly applicable, with some of the primal weirdness of myth.

I note also that there are direct echoes of politics in the Philippines, past and present. Dayao’s spoken about how he had the Marcos era more on his mind than the Duterte regime, but then he’s also said that he sees the film as fundamentally the story it appears to be — not a coded allegory for politics but a fantasy-horror tale. I certainly don’t know enough to speculate about political parallels. But the way the characters struggle with mysterious powers, with a society that operates by unknown rules, feels like a general observation about people in society; whatever specific points Dayao’s making, it is I think broadly applicable, with some of the primal weirdness of myth.

There’s certainly an effective horror feel. Dayao demonstrates a knack for knowing what needs to be explained and what can be left as mysteries. In horror, leaving things unexplained can instill a sense of rules just beyond knowledge, or can instill a sense of randomness. The second is usually bad; if anything can happen at any time, there’s no real dramatic suspense. But the first is deeply powerful and disturbing. Midnight In A Perfect World manages the trick. It’s not a film interested in neatly articulating all the reasons why things happen, but you do believe those reasons exist. The movie profits by its lack of neatness. It’s the good kind of messy, the kind that lets a raw creativity peek through the things it leaves undefined.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.