Fantasia 2021, Part LIX: Midnight

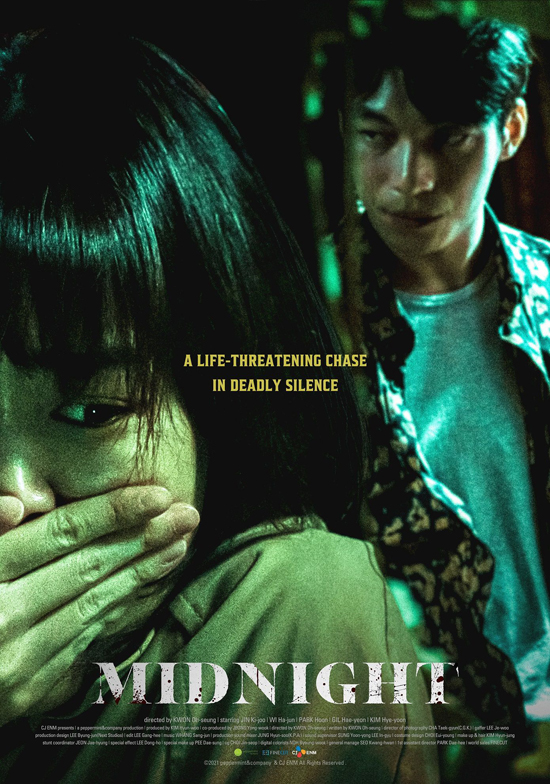

Midnight (미드나이트, Mi-deu-nai-teu) is a suspense thriller from Korea that revolves around Kyung-mi (Ki-joo Jin), a young deaf woman who, one night on her way to meet her mother (Hae-yeon Kil), comes across a grievously wounded woman named So-jung (Kim Hye-Yoon). So-jung’s been attacked by a maniacal serial killer, Do-sik (Wi Ha-Joon, Squid Game), who now sees Kyung-mi and selects her as his next victim. Meanwhile, So-jung’s frantic brother (Park Hoon) is desperately trying to find his sister. Whether he’ll be able to help the women is unclear; Do-sik’s crafty, daring, and manipulative. But Kyung-mi’s resourceful herself.

Midnight (미드나이트, Mi-deu-nai-teu) is a suspense thriller from Korea that revolves around Kyung-mi (Ki-joo Jin), a young deaf woman who, one night on her way to meet her mother (Hae-yeon Kil), comes across a grievously wounded woman named So-jung (Kim Hye-Yoon). So-jung’s been attacked by a maniacal serial killer, Do-sik (Wi Ha-Joon, Squid Game), who now sees Kyung-mi and selects her as his next victim. Meanwhile, So-jung’s frantic brother (Park Hoon) is desperately trying to find his sister. Whether he’ll be able to help the women is unclear; Do-sik’s crafty, daring, and manipulative. But Kyung-mi’s resourceful herself.

Writter-director Oh-Seung Kwon presents a Hitchcockian story in which an unsuspecting and basically innocent person finds themself isolated from society by a scheming, ruthless murderer. There are scenes with security officers that demonstrate how adept Do-sik is at using the system and turning it against itself; there’s no help for Kyung-mi from that quarter. Involving the police, or indeed any outside source, just gives Do-sik more tools to use.

The film unfolds over the course of a single night, not quite in real time, and the lack of any major temporal jumping-forward emphasises the remorselessness of events. If things are sometimes convenient for the plot, as can be the case in Hitchcockian thrillers, then having everything take place in one stretch of time helps: Do-sik doesn’t need to come up with permanent con games, he just needs to keep people busy and set things up so he can do what he wants. The background of night in a big city works as well; the cityscapes are mostly empty, streets unpopulated. I don’t know how much of a part budget concerns played in the lack of extras, but it’s effective in building the sense of isolation. There’s nobody to help, nobody to see violence play out. Only quiet houses and deserted streets.

On a deeper level, the film works because it’s a solid dramatic structure. The characters all have clear goals, and these goals put them in conflict with each other, and we see how that conflict works out. The film gives Do-sik a bit of help; some plot points make things a lot easier for him. A crime scene is cleaned up awfully quickly. Security officers are maybe more bumbling than you’d expect, and are distracted easily. But there’s a thing that happens in thrillers, like this one, where that sort of thing only amplifies the tension: the story seems to be helping the villain in small ways, and that increases the feel of nightmare, the feel of an irrational world supporting a threat that doesn’t operate according to fair-play rules of logic.

But in fact Do-sik is not a supernatural creature, is merely human, and can be fought and stopped. It’s just not going to be easy for the other characters. And the film succeeds because we see how the other characters, principally Kyung-mi, are pushed to their limits in trying to end his threat.

In particular the film works because of its depiction and use of Kyung-mi’s deafness. I am not hearing impaired, so take it for what it’s worth, but I was impressed with how her lack of hearing becomes a strength in the film. Unsurprisingly there are scenes in which we see a threat coming that she does not perceive because of her deafness, but there are also scenes where (for example) her ability to communicate with her mother in sign language is critically important. The film does a good job right from her opening scenes of establishing her deafness as a major part of her life without allowing it to principally define her.

In particular the film works because of its depiction and use of Kyung-mi’s deafness. I am not hearing impaired, so take it for what it’s worth, but I was impressed with how her lack of hearing becomes a strength in the film. Unsurprisingly there are scenes in which we see a threat coming that she does not perceive because of her deafness, but there are also scenes where (for example) her ability to communicate with her mother in sign language is critically important. The film does a good job right from her opening scenes of establishing her deafness as a major part of her life without allowing it to principally define her.

From a slightly more technical perspective, the film does some excellent work with soundscapes and aural point-of-view. Film typically uses point-of-view more subtly than in prose — limited third-person prose is obviously different from first person or (usually) omniscient third-person, and for most audiences camerawork doesn’t always establish that sort of distinction as quickly and easily. Sound, though, at least in this case, is an immediate way to establish whose head we’re in and whose perspective is at the centre at any given moment. Beyond the sensory pleasure of an unexpected rhythm of silence and sound, beyond the clever narrative uses of sound, there’s a good use of sonic perspective to help establish character and identification with character. When we hear nothing on the soundtrack, we’re all in Kyung-mi’s situation.

Generally the film’s strong in its development of character. As I said, all the main figures have their own desires and act on them, and some contradict each other and some are in parallel but not obviously so. Sympathetic characters can make choices that are clearly wrong, set up for them by Do-sik, but we understand why they make those choices and why the choices make sense. The flip side’s also true: Do-sik has the arrogance of the narcissist, and in the end that trips him up. He doesn’t grasp how clever and daring other people can be.

Generally the film’s strong in its development of character. As I said, all the main figures have their own desires and act on them, and some contradict each other and some are in parallel but not obviously so. Sympathetic characters can make choices that are clearly wrong, set up for them by Do-sik, but we understand why they make those choices and why the choices make sense. The flip side’s also true: Do-sik has the arrogance of the narcissist, and in the end that trips him up. He doesn’t grasp how clever and daring other people can be.

In speaking of the film’s character work, particularly worth noting is Kyung-mi’s relationship with her mother. The two women work together well, and it’s an interesting relationship to see play out in this context. On a practical level, it gives Kyung-mi another deaf character to interact with. But it’s so unusual to see a woman of the mother’s age with an active role in a thriller film, much less one with a disability, that it gives the film another bit of distinctiveness.

It’s also possible to see the use of her as a character as a way to explore who gets social capital and who does not. Before the thriller plot kicks in we see Kyung-mi at her job, see her relative to her bosses, see her status as a woman in her workplace, see how her deafness complicates things. We see Do-sik manipulating police officers, see how he’s trusted because he’s a man who knows how to present himself. Later on, Kyung-mi and her mother don’t get the same kind of immediate respect. There’s an anti-patriarchal subtext to a lot of the film — the title comes in part out of an argument So-jung has with her brother, who tries to enforce a curfew. And the climax involves playing about with the perception of onlookers at a crucial point, again dealing with questions of social capital and who gets reflexively believed about what.

It’s also possible to see the use of her as a character as a way to explore who gets social capital and who does not. Before the thriller plot kicks in we see Kyung-mi at her job, see her relative to her bosses, see her status as a woman in her workplace, see how her deafness complicates things. We see Do-sik manipulating police officers, see how he’s trusted because he’s a man who knows how to present himself. Later on, Kyung-mi and her mother don’t get the same kind of immediate respect. There’s an anti-patriarchal subtext to a lot of the film — the title comes in part out of an argument So-jung has with her brother, who tries to enforce a curfew. And the climax involves playing about with the perception of onlookers at a crucial point, again dealing with questions of social capital and who gets reflexively believed about what.

If there is a weakness to the thriller plot, it’s that the climax feels a little drawn-out. It’s structurally sound, paying off a lot of beats set up earlier on, and as I say thematically it resonates with the rest of the film. But as Do-sik’s schemes start to unravel, you can see the end coming for him. There’s some pleasure in seeing the tables turned, as he must struggle for survival in the way his victims did earlier, but here his narcissism is too well-played: he never thinks he’s going to lose even when we as viewers know it’s inevitable.

But in general this is a very strong and very effective suspense movie that does good character work and has an intriguing hook that plays out through a good use of the medium. The villain’s memorable, the heroine’s struggle is involving, and there’s enough on the movie’s mind that the subtext gives us something more than just what we see. Or hear. This is a movie that knows what it wants to do, and does it extremely well.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.