Fantasia 2021, Part XLVII: Kakegurui 2: Ultimate Russian Roulette

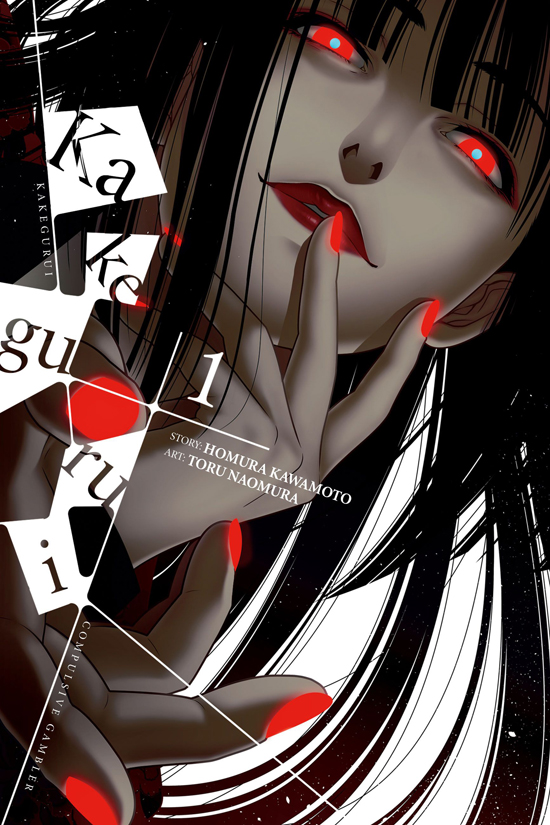

Last year I reviewed a movie called Kakegurui (映画 賭ケグルイ, Eiga: Kakegurui). This year served up Kakegurui 2: Ultimate Russian Roulette (also Kakegurui Part 2: Desperate Russian Roulette, originally 映画 賭ケグルイ絶体絶命ロシアンルーレット, Kakegurui the Movie: Zettai Zetsumei Russian Roulette), the second movie in the franchise, like the first directed by Tsutomu Hanabusa and co-written by him with Minato Takano. And this is indeed a franchise; starting with a manga (written by Homura Kawamoto and illustrated by Toru Naomura) it branched out to an anime, a live-action TV show (streaming on Netflix), and these two live-action films starring the cast of the TV show — as well as spin-off manga, light novels, and a now-discontinued video game. After being entertained by the first movie last year I added the show to my Netflix queue, although I haven’t watched it yet (I have only so much time to dedicate to watching TV, and the Criterion Channel has a lot of films and many of them are really good). The second movie played this year’s Fantasia bundled with the first one, and remembering that there was a lot of plot in the first, I decided to check it out again and then catch the sequel.

Last year I reviewed a movie called Kakegurui (映画 賭ケグルイ, Eiga: Kakegurui). This year served up Kakegurui 2: Ultimate Russian Roulette (also Kakegurui Part 2: Desperate Russian Roulette, originally 映画 賭ケグルイ絶体絶命ロシアンルーレット, Kakegurui the Movie: Zettai Zetsumei Russian Roulette), the second movie in the franchise, like the first directed by Tsutomu Hanabusa and co-written by him with Minato Takano. And this is indeed a franchise; starting with a manga (written by Homura Kawamoto and illustrated by Toru Naomura) it branched out to an anime, a live-action TV show (streaming on Netflix), and these two live-action films starring the cast of the TV show — as well as spin-off manga, light novels, and a now-discontinued video game. After being entertained by the first movie last year I added the show to my Netflix queue, although I haven’t watched it yet (I have only so much time to dedicate to watching TV, and the Criterion Channel has a lot of films and many of them are really good). The second movie played this year’s Fantasia bundled with the first one, and remembering that there was a lot of plot in the first, I decided to check it out again and then catch the sequel.

What I said last year still applies. The movies are set at a private school in Japan for the rich and powerful, with no adults or fixed classes; the curriculum is entirely based around gambling, as students bet vast sums in complex games of chance. Students who lose too much money become the pets of the winners, kitties if girls and doggies if boys. A tyrannical student council oversees the whole affair, but is troubled by a mysterious transfer student named Yumeko (Minami Hamabe, also of Ajin: Demi-Human), our heroine. The first movie follows events at the school as a village of anti-gambling students secede from the main campus.

The second movie jumps forward in time; I’m not sure how these films fit in with the continuity of the TV shows, but a few things make this one feel as though a season’s worth of adventures have happened since the first. At any rate, the student council, having grown thoroughly fed up with Yumeko, bring in a ringer named Shikigami (Ryusei Fujii) to deal with her. He wins his games in cut-throat fashion, blackmailing or threatening his opponents with physical force against those they love, and threatens to destabilise the whole school. Meanwhile, income inequality is spreading, as more and more students are reduced to the state of being pets, in turn reducing the number of gamblers.

The second movie jumps forward in time; I’m not sure how these films fit in with the continuity of the TV shows, but a few things make this one feel as though a season’s worth of adventures have happened since the first. At any rate, the student council, having grown thoroughly fed up with Yumeko, bring in a ringer named Shikigami (Ryusei Fujii) to deal with her. He wins his games in cut-throat fashion, blackmailing or threatening his opponents with physical force against those they love, and threatens to destabilise the whole school. Meanwhile, income inequality is spreading, as more and more students are reduced to the state of being pets, in turn reducing the number of gamblers.

The feel of the second movie is much the same as the first one: frenetic comedic running-around; imaginative staging and costuming; lots of practical effects creating a zany, unreal world; candy colours to every hand; a quick-twisting plot in which enemies become allies, or at least useful pawns; and games of chance and skill worked deeply into the plot. Both films set up several subplots, show a couple of relatively quick games in the first half, and then have a second half largely dominated by a single sprawling game in which various schemes and betrayals are enacted. The second movie feels a bit simpler than the first, with fewer subplots, but both are clever and quick enough to work.

In particular the gambling’s used very well to set up character through significant choices. The rules of the games are laid out clearly, and how the different characters play the games tells us about those characters. It would have been very easy for the games to feel as though intruding into the plot, or for the explanations of their rules to be clunky infodumps, and neither of these things happen. The multi-player Russian roulette that becomes the centrepiece of the second movie is particularly interesting, an exercise in trust and scheming that goes very interesting places. More generally, the movies thoughtfully gives each of the different master-gambler characters they introduce different powers — different ways by which they win their games. In good comic-book fashion, these different powers derive from their different personalities.

In particular the gambling’s used very well to set up character through significant choices. The rules of the games are laid out clearly, and how the different characters play the games tells us about those characters. It would have been very easy for the games to feel as though intruding into the plot, or for the explanations of their rules to be clunky infodumps, and neither of these things happen. The multi-player Russian roulette that becomes the centrepiece of the second movie is particularly interesting, an exercise in trust and scheming that goes very interesting places. More generally, the movies thoughtfully gives each of the different master-gambler characters they introduce different powers — different ways by which they win their games. In good comic-book fashion, these different powers derive from their different personalities.

Thus Shikigami, who wins through a specific kind of brute force, applied not in the game but around it. He realises that the game is just a game, but death threats can be applied to force his opponents to choose what really matters to them, which is rarely the game. There’s a grimness to him that makes for an interesting contrast with Yumeko, who is detached and ironic except when she’s engaged in gambling, at which point the thrill of the sport brings her to a kind of ecstasy.

Which is also to say that the fetishistic sexuality is still present in the second movie. The humiliation of losers, the exercise of power, the look of the characters in their cartoony uniforms — it’s perhaps less subtext than domtext, but the literal story is remarkably chaste. I’m not sure there’s so much as a kiss onscreen, or any dramatic confession of romantic attraction. I note that the films don’t go into detail about the pets and their humiliations, don’t linger over punishments beyond the moment of victory and defeat. On the other hand, I wonder how much the way the characters use and subvert the image of the schoolgirl has a meaning to it.

Which is also to say that the fetishistic sexuality is still present in the second movie. The humiliation of losers, the exercise of power, the look of the characters in their cartoony uniforms — it’s perhaps less subtext than domtext, but the literal story is remarkably chaste. I’m not sure there’s so much as a kiss onscreen, or any dramatic confession of romantic attraction. I note that the films don’t go into detail about the pets and their humiliations, don’t linger over punishments beyond the moment of victory and defeat. On the other hand, I wonder how much the way the characters use and subvert the image of the schoolgirl has a meaning to it.

If the second film neither increases or decreases the sexuality of the story, it does dial up the class conflict even further. The increase of pets ties directly into the main tale, and coincidentally or not seems to speak to increasing income inequality. By focussing on the student council leaders the movie also emphasises the way power’s exercised in the school. We see the council working out how to deal with Yumeko, less a direct rebel than a factor they cannot control. This may be the real fetish of the rich, not sexuality but control; and so they take action, and the plot of the movie unfurls. Here and in the first movie we see the council try to subvert and manipulate their opponents, which is certainly possible to read as a comment on the way power structures work.

The second movie has no equivalent to the groups of students in the first movie who were opposed to the structure of the school. There’s a kind of skepticism here of principled rebels; Yumeko’s more of a mystery, a wild card. This sidesteps the question of how to defeat a monster without becoming a monster, and whether the tools the student council allows their enemies can really be used to defeat the council; another point in the movies’ class-consciousness is their awareness the rich can rig things in their favour.

The second movie has no equivalent to the groups of students in the first movie who were opposed to the structure of the school. There’s a kind of skepticism here of principled rebels; Yumeko’s more of a mystery, a wild card. This sidesteps the question of how to defeat a monster without becoming a monster, and whether the tools the student council allows their enemies can really be used to defeat the council; another point in the movies’ class-consciousness is their awareness the rich can rig things in their favour.

It’s also notable that the games in both movies have an element of the popularity contest to them. That speaks to the high school setting, of course, but it may also speak to social media in a way the films otherwise don’t tackle — these are the least online kids I’ve seen in real life or on film. At any rate, part of the way popularity’s used in the games means that slight advantages early on can swiftly lead to massive advantages as the game goes on, which strikes me as a sharp observation on how social class works.

Yumeko is an interesting protagonist not because she has an obvious burning desire to defeat her enemies, but because she’s got plans behind her facade and it’s intriguing watching her put them into practice. In the first movie she says that “to fool the enemy, one must fool one’s friends first,” and this points to an amorality that’s intriguing. In fact whatever else is going on she celebrates gambling for the thrill of it, the pure joy of risk: “Bring on the madness!” she cries in both movies, which is a line that at the films best could serve as their mission statement. It also points to a purity in Yumeko’s character: for her, as for perhaps no-one else at the school, gambling means something in itself.

Yumeko is an interesting protagonist not because she has an obvious burning desire to defeat her enemies, but because she’s got plans behind her facade and it’s intriguing watching her put them into practice. In the first movie she says that “to fool the enemy, one must fool one’s friends first,” and this points to an amorality that’s intriguing. In fact whatever else is going on she celebrates gambling for the thrill of it, the pure joy of risk: “Bring on the madness!” she cries in both movies, which is a line that at the films best could serve as their mission statement. It also points to a purity in Yumeko’s character: for her, as for perhaps no-one else at the school, gambling means something in itself.

I’ve written a lot here about movies that are essentially quick-paced comedy-satires with good exaggerated performances and a weird setting. Both Kakegurui movies are films that know what they are and what they’re doing, and do it well, and have fun doing it. But like the best pop culture, they build good solid entertainment out of telling sharp stories with resonant ideas; and what makes the ideas resonant is the way they seem to speak to something about the world and about human nature, and so provide food for thought. There’s not much more you can ask of these movies.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

These films sound seriously strange. Are the dubbed, or captioned, or both?