Fantasia 2021, Part XlV: Glasshouse

“Cloud” is a 29-minute film from France, directed by Joséphine Darcy Hopkins and written by Hopkins with Jean-Jacques Kahn. Hopkins is part of Les Films de la Mouche, a collective that (per ScreenAnarchy) aims to “mix very personal obsessions with ‘genre grammar.’” That’s visible here, in a story about a radioactive cloud descending on a small town, which prompts 15-year-old Eugénie (Cypriane Gardin) to run away with her friend Capucine (Solène Rigot) and Capucine’s ailing mother (Catherine Salée). The movie takes some unpredictable twists, and spends much of its time as an unusual character-centred buddy movie. It looks very nice, with some lovely natural backgrounds in a forest at night and among the mountains by day; the threat of the cloud is sometimes distant, but never entirely absent, flavouring the story with a science-fictional overtone. I thought the ending was a touch too ambiguous, but then again it’s difficult to see a better resolution.

“Cloud” is a 29-minute film from France, directed by Joséphine Darcy Hopkins and written by Hopkins with Jean-Jacques Kahn. Hopkins is part of Les Films de la Mouche, a collective that (per ScreenAnarchy) aims to “mix very personal obsessions with ‘genre grammar.’” That’s visible here, in a story about a radioactive cloud descending on a small town, which prompts 15-year-old Eugénie (Cypriane Gardin) to run away with her friend Capucine (Solène Rigot) and Capucine’s ailing mother (Catherine Salée). The movie takes some unpredictable twists, and spends much of its time as an unusual character-centred buddy movie. It looks very nice, with some lovely natural backgrounds in a forest at night and among the mountains by day; the threat of the cloud is sometimes distant, but never entirely absent, flavouring the story with a science-fictional overtone. I thought the ending was a touch too ambiguous, but then again it’s difficult to see a better resolution.

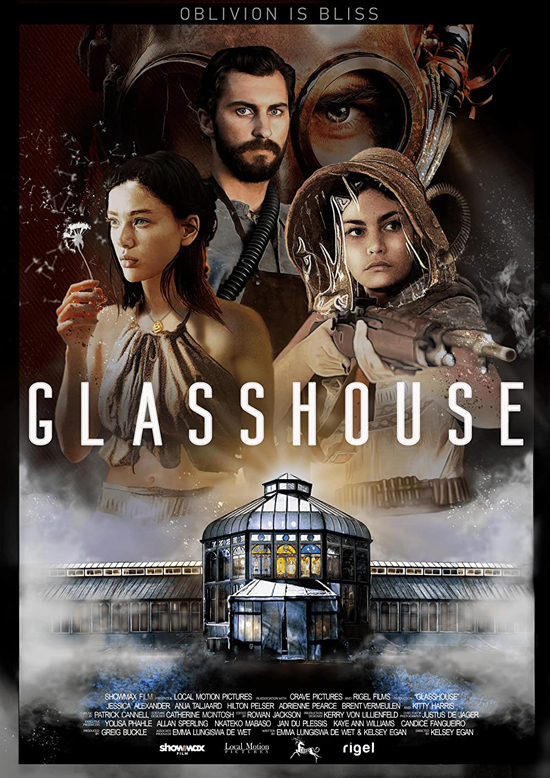

Along with the short came Glasshouse, a post-apocalyptic tale from South Africa and director Kelsey Egan, who co-wrote with Emma De Wet. It’s set some time in the future, when Earth’s atmosphere’s been contaminated by a plague called the Shred, which destroys human memories. One small family — consisting of an old matriarch (Adrienne Pearce), three sisters, and a brain-blasted brother (Brent Vermeulen) — all live together holed up in an expansive greenhouse, a self-sufficient ecosystem where the plants create clean air (don’t ask where the family’s protein comes from, because I don’t know and the film isn’t really interested in that kind of detail). A mysterious stranger (Hilton Pelser) enters the house from outside, his memories apparently more-or-less intact, disrupting the family dynamic and unearthing old secrets. The oldest sister, Bee (Jessica Alexander) is drawn to him; the mother is more suspicious.

The movie’s got a strong visual sensibility, and was shot inside an actual colonial-era greenhouse in South Africa. The costumes are a Victorian-Edwardian hallucination of bonnets and dresses, and the props are a mix of utilitarian and frivolous. That same mixture of adjectives also applies to sexuality in the film; the advent of the mysterious stranger stirs up tensions between the sisters, but at the same time maturing humans have desires that are best fulfilled, and so ways are found in this odd family. There is a coldness to sexual desire in Glasshouse, ironic in the literal hothouse setting, and this gives the picture a keen edge.

Unfortunately the plot otherwise is uneven. The ideas are strong, but the execution has a tendency to fall into melodrama, with some of the major emotional beats given a weight they don’t support. There’s also, a bit paradoxically, a stillness to the film. Some of that’s the nature of the frozen environment, maybe, but the plot movement unfurls slowly, and I found the soundtrack (fine in itself) had a tendency to reinforce the static feel of events.

Nevertheless, as a whole the story’s effective. The memory-depriving plague is used well to set up a variety of situations. The mysteries and doubts of the film work even when the tension between the characters fails. There’s also a great final twist in the last few seconds of the movie, and in fact it’s so strong, casting all we’ve seen in a new and richer light, that I wonder if it might profitably have been moved forward. It felt like the kind of logical and powerful jolt that the story could have used earlier on.

Nevertheless, as a whole the story’s effective. The memory-depriving plague is used well to set up a variety of situations. The mysteries and doubts of the film work even when the tension between the characters fails. There’s also a great final twist in the last few seconds of the movie, and in fact it’s so strong, casting all we’ve seen in a new and richer light, that I wonder if it might profitably have been moved forward. It felt like the kind of logical and powerful jolt that the story could have used earlier on.

I’m probably wrong in that instinct. Certainly I can think of thematic reasons why the revelation comes when it does. This is a film that has to do with archetype and storytelling and the relationship of stories and identity and memory, and the twist speaks to all of those. So there’s sense in placing it as the capstone. My problem, I suppose, is that the drama leading up to it does not to my eyes have the resonance of archetype — which is something that does come out in the final twist.

I may be looking for archetype in the wrong places. It strikes me that the film can be read as the story of a male figure struggling for control of a matriarchal society; if so, it’s similar to one myth of prehistory in which matriarchal societies were conquered by patriarchal tyrants. Here the situation’s more ambiguous — the matriarch at the start of the film is herself tyrannical, and the ending takes a slightly different shape. But there is a sense of cycles of time and memory and culture at work, even in a glasshouse that by its nature works to keep natural cycles in check, and particularly works to keep the seasons in a stasis.

I may be looking for archetype in the wrong places. It strikes me that the film can be read as the story of a male figure struggling for control of a matriarchal society; if so, it’s similar to one myth of prehistory in which matriarchal societies were conquered by patriarchal tyrants. Here the situation’s more ambiguous — the matriarch at the start of the film is herself tyrannical, and the ending takes a slightly different shape. But there is a sense of cycles of time and memory and culture at work, even in a glasshouse that by its nature works to keep natural cycles in check, and particularly works to keep the seasons in a stasis.

Certainly the film’s creators are aware of the symbolic power of the story and the way it speaks to a range of themes. In a question-and-answer session, they discussed colonialism in South Africa and how moving past colonialism as a country means a kind of strategic forgetting of the past. The struggle of the inhabitants of the glasshouse not to let the Shred in, not to let the outside air in, then could be seen as a clinging to comforting past ways that deny the actual reality around them. There is something very like Northrop Frye’s garrison mentality to the glasshouse — a demarcated space in which a certain kind of ‘civilisation’ is maintained in the face of a hostile natural world.

Themes that have political and historical resonance usually work to best enrich a story when those resonances are themselves part of a broader human meaning. That is, politics and history are human things, and so the themes that run through them are the themes that run through human beings; well-told tales can therefore be self-consistent stories on one level, speak to political realities at a deeper level, and then through the themes in the politics speak to something deeply human. So it is here, because in speaking about colonialism and gender the film’s also talking about power and the exercise of power; and it is talking about identity, and how identity is shaped by the past and what one remembers of the past.

Themes that have political and historical resonance usually work to best enrich a story when those resonances are themselves part of a broader human meaning. That is, politics and history are human things, and so the themes that run through them are the themes that run through human beings; well-told tales can therefore be self-consistent stories on one level, speak to political realities at a deeper level, and then through the themes in the politics speak to something deeply human. So it is here, because in speaking about colonialism and gender the film’s also talking about power and the exercise of power; and it is talking about identity, and how identity is shaped by the past and what one remembers of the past.

Especially, in talking about these things, the movie’s talking about storytelling. And about how stories take on certain shapes: again, archetypes. The setting is literally a garden in which good and evil as we understand them are unknown, or at least forgotten. And then there comes an intruder into the garden. Like the serpent to Eden, perhaps like Hades to Persephone. The characters are living out a primal story, but which one? The stranger tells them a tale of his past; it’s a story some of them want to hear. Does it matter if it’s true or not? Or is it enough that it be believed? What other stories are they (and we the viewers) believing without being aware enough to doubt them?

The film’s got some strong ideas, and some excellent performances. I don’t think (at one viewing) that it’s a total success. But there’s a lot going on in the story. I think it hides some of its strongest ideas for too long. But those ideas are present, and when they come out suggest a second viewing could profitably reveal more depth than is clear the first time around. The oddity of the science-fictional premise is used with full consciousness of its symbolic potential. For me, that’s not clear from the structure of events as the movie unfurls. Others may be more perceptive.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.