Fantasia 2021, Part XXXVIII: The Feast

“In the Soil” (“Det er i jorden”) is a 14-minute Danish film from writer-director Casper Rudolf Kjeldsen with a disquieting atmosphere. A man (Thomas Guldberg Madsen) and his adult daughter (Sandra Guldberg Kampp) live in the country. He grows fascinated with a plot of land by his house, and begins to dig it up, obsessively spending all his time at it. His daughter helps him, but has misgivings. Will she become obsessed as well? What will happen to the father as he finishes his pit? And what does it all mean? I can answer the first two questions, but I’m not sure about the third. What literally happens is clear, but why things unfold as they do is more obscure, at least at one viewing. The movie lives in its atmosphere, its dark and oppressive visual sense, and it may be that the mesmeric pace creates the sense of more meaning than the story can provide. It’s an interesting and uneasy experience, but I could get no sense of a theme.

“In the Soil” (“Det er i jorden”) is a 14-minute Danish film from writer-director Casper Rudolf Kjeldsen with a disquieting atmosphere. A man (Thomas Guldberg Madsen) and his adult daughter (Sandra Guldberg Kampp) live in the country. He grows fascinated with a plot of land by his house, and begins to dig it up, obsessively spending all his time at it. His daughter helps him, but has misgivings. Will she become obsessed as well? What will happen to the father as he finishes his pit? And what does it all mean? I can answer the first two questions, but I’m not sure about the third. What literally happens is clear, but why things unfold as they do is more obscure, at least at one viewing. The movie lives in its atmosphere, its dark and oppressive visual sense, and it may be that the mesmeric pace creates the sense of more meaning than the story can provide. It’s an interesting and uneasy experience, but I could get no sense of a theme.

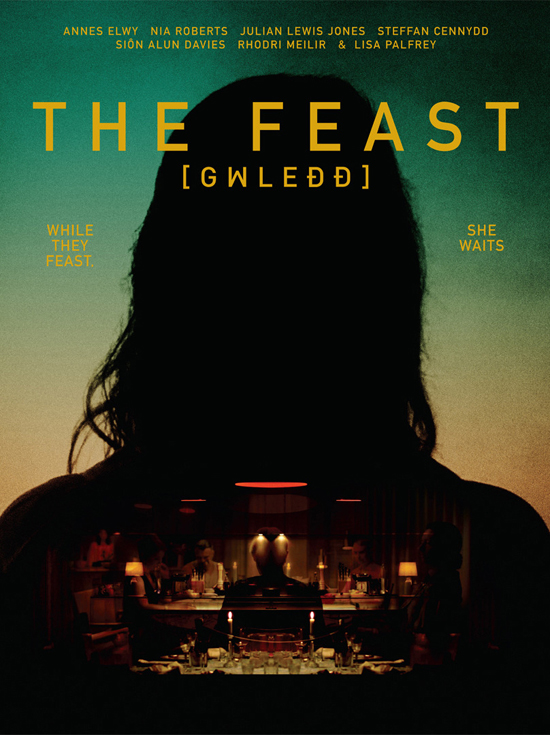

Bundled with it was The Feast, the first feature-length horror movie performed entirely in Welsh. As you might expect, it’s set in the Welsh countryside, where the family of an MP (Julian Lewis Jones) prepares to give a dinner for friends and associates. It’s secretly a business dinner, to do with plans for the local land, and MP Gwyn and his wife Glenda (Nia Roberts) have hired extra help for the night, a silent young woman named Cadi (Annes Elwy). Their sons, Guto (Steffan Cennydd) and doctor Gweirydd (Sion Alun Davies) are also present in their clean, right-angled modernist house set among the riot of green hills. At first, and for some time, things move along normally if slowly. But then odd things come to the fore, violence emerges, and it becomes clear what sort of a story we are watching.

This is a folk horror tale about the land taking its revenge on those who would defile it. The use of the Welsh language is thus more than a gimmick: it’s relevant to the theme, an assertion of cultural history. Gwyn and his family are Welsh by origin, and to an extent by upbringing, but have turned away from their background to cash in on the opportunities of big politics and big business. Which is to say there’s implicitly an anti-colonial theme to this story.

It works, because the political implications flavour a story that’s primarily about individual characters and their greed and how that greed manifests. The idea of revolt against wealth and unchecked resource extraction is simple, but Gwyn’s family becomes a believable manifestation of greater ills. Gwyn thinks nothing of using his position to make deals of questionable legality. His sons think nothing of anyone but themselves. And Glenda’s turned away from her family’s rootedness in the land, ignores old tales about powers that should not be disturbed, has almost forgotten the old folk songs that Cadi sings; she keeps a clean house, a new house defined by straight lines and a lack of interaction with the surrounding geography.

Narratively, the horror imagery is central. It takes a while to arrive. But it is bloody and powerful when it does, in large part because the way has been prepared in both plot and emotional terms. There is a very specific chilly atmosphere to the early part of the film — no sun-dappled exteriors here, only a grim grey light under thick clouds, next to which even the clinical house feels almost warm. And this atmosphere subtly moves us into a mental space where grim deeds are possible.

Narratively, the horror imagery is central. It takes a while to arrive. But it is bloody and powerful when it does, in large part because the way has been prepared in both plot and emotional terms. There is a very specific chilly atmosphere to the early part of the film — no sun-dappled exteriors here, only a grim grey light under thick clouds, next to which even the clinical house feels almost warm. And this atmosphere subtly moves us into a mental space where grim deeds are possible.

Some plot points are underdeveloped. Notably, subplots involving the sons never go anywhere; a scandal involving Gweirydd is mentioned, but never becomes directly relevant to the film. And a couple of moments of violence appear unmotivated. I suspect there are reasons behind them that I’d pick up on a second viewing, but I also suspect I should be able to work out what’s happening at one go. (By contrast, there’s a bit of nastiness with a piece of broken glass that perplexed me for a bit but which became clear with some thought, and that felt just right in terms of the amount of effort it took to figure out.) Still, if occasionally perplexing in specifics, the general idea of what’s going on with the characters is clear.

So too is the general theme of the revenge of the land against exploitation. The contrast of house and landscape is a lovely visual bit of business to establish this point: the house built out of rectangles and squares and straight lines, against the curving slopes and grasses. This then is worked out remorselessly throughout the film. Cadi’s old folk songs alert us that something is up with her. Glenda dismissively mentions her mother’s old things that would not fit in with the new house; she is deracinated, tearing up her own roots to move into a future bought by a betrayal of the past.

So too is the general theme of the revenge of the land against exploitation. The contrast of house and landscape is a lovely visual bit of business to establish this point: the house built out of rectangles and squares and straight lines, against the curving slopes and grasses. This then is worked out remorselessly throughout the film. Cadi’s old folk songs alert us that something is up with her. Glenda dismissively mentions her mother’s old things that would not fit in with the new house; she is deracinated, tearing up her own roots to move into a future bought by a betrayal of the past.

It’s interesting, in fact, to consider what the story gets out of exploring this basic situation through the horror genre. In that context, if you’re plotting the exploitation of the rural Welsh landscape, and you bring into your home a young lady with a thousand-yard stare who seems not to quite grasp the modern world and sings old songs about the crow king … you may not be about to give the most successful dinner party in history. But if you’re in an arthouse movie, or a literary novel, that same character might merely represent an elegiac sense of alienation from the traditions of the land. The merely symbolic in realist fiction becomes literally powerful in genre fiction.

Or to put it another way, in genre it’s easier to see the emotional connection with the land come to dominate financial power relations. That could be viewed as wish-fulfilment, or a displaced power fantasy. But you could also see it as an acknowledgement that the unconscious cannot be long denied: the irrational, animal part of the psyche will inevitably emerge the more one tries to repress it. In that sense, the exploitation of the land is symbolically an attempt to exploit the irrational, to quarry out a part of oneself. Just as the geometrically precise modernist house imposes well-measured forms on organic landscape, the attempt to dig up the guts of the earth is an attempt to tame the intractable wilderness, to make it profitable according to rational financial calculations. This sort of contrast is not uncommon in Canadian literature — Northrop Frye wrote about a ‘garrison mentality’ in Canadian fiction in which settlers build straight and solid walls to isolate themselves from a threatening nature, and in so doing cut themselves off from a part of themselves. Something like that happens here in a Welsh story, except that the horror form makes it easier to show the land lashing back, and allows that backlash to be more stunning and cruel.

Or to put it another way, in genre it’s easier to see the emotional connection with the land come to dominate financial power relations. That could be viewed as wish-fulfilment, or a displaced power fantasy. But you could also see it as an acknowledgement that the unconscious cannot be long denied: the irrational, animal part of the psyche will inevitably emerge the more one tries to repress it. In that sense, the exploitation of the land is symbolically an attempt to exploit the irrational, to quarry out a part of oneself. Just as the geometrically precise modernist house imposes well-measured forms on organic landscape, the attempt to dig up the guts of the earth is an attempt to tame the intractable wilderness, to make it profitable according to rational financial calculations. This sort of contrast is not uncommon in Canadian literature — Northrop Frye wrote about a ‘garrison mentality’ in Canadian fiction in which settlers build straight and solid walls to isolate themselves from a threatening nature, and in so doing cut themselves off from a part of themselves. Something like that happens here in a Welsh story, except that the horror form makes it easier to show the land lashing back, and allows that backlash to be more stunning and cruel.

It should never be forgotten that this is a horror movie, after all. There is certainly formal ambition here in the precision of soundscapes and cinematography, and in the measured pacing and slow build of the story. But this is folk horror that knowingly uses folk horror traditions. In that light, it’s amusing to note that one of the secondary characters, as soon as she realises what Gwyn has planned, immediately leaves. She understands that digging in a forbidden part of the land will have no good result. And understands that she does not want to be part of a horror movie. So she says quick goodbyes and goes, and thus a sensible middle-aged Welsh lady gets the better of horror tropes. It’s symbolically right — the character who respects traditions survives — but it’s also a nice bit of commentary on the genre. Which is a microcosm of why The Feast works: it marries a cinematic intelligence with an understanding of its genre form.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

This one sounds right up my alley. But I hope it has subtitles! 🙂