Fantasia 2021, Part XXXIV: The Slug

“Noses On the Run” (“내 코가 석재”) is a 20-minute short film from Korea written and directed by Kim Boram. In the near future a woman with extreme chronic rhinitis is desperate for respite from her condition. Salvation seems at hand when she’s able to order a new nose online. But a mistake has been made, and there will be consequences. It’s a movie full of low-key oddity and a dramatic climax; it looks nice, and speaks to the nature of suffering from a chronic illness. It’s a bit slow to get to its protagonist’s main dramatic choice, but the set-up’s visually interesting enough that the movie works as a whole.

“Noses On the Run” (“내 코가 석재”) is a 20-minute short film from Korea written and directed by Kim Boram. In the near future a woman with extreme chronic rhinitis is desperate for respite from her condition. Salvation seems at hand when she’s able to order a new nose online. But a mistake has been made, and there will be consequences. It’s a movie full of low-key oddity and a dramatic climax; it looks nice, and speaks to the nature of suffering from a chronic illness. It’s a bit slow to get to its protagonist’s main dramatic choice, but the set-up’s visually interesting enough that the movie works as a whole.

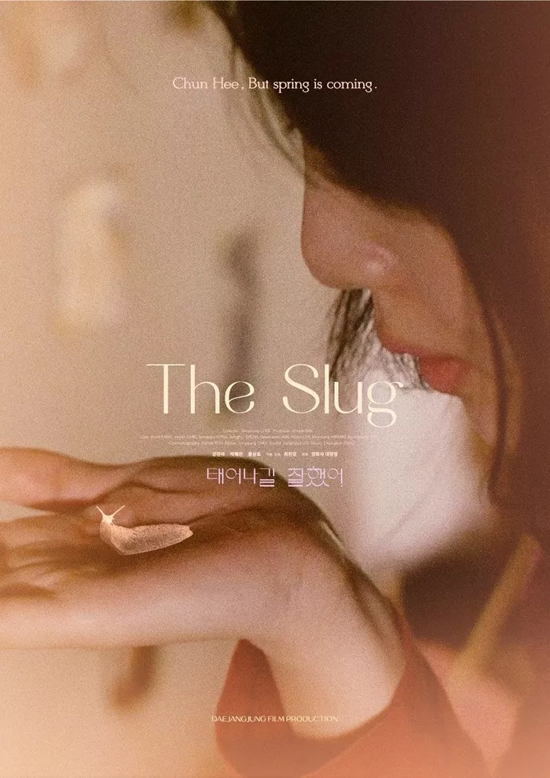

Bundled with the short was the feature film called The Slug (태어나길 잘했어, Tae-eu-na-gil Jal-hat-eo), also from Korea. Written and directed by Choi Jin-young, it’s a movie that interlaces past with present as a way of presenting one woman’s life. Chun-hee (Kang Jin-ah) lives alone in the house where she came to live in her teen years with her aunt and uncle and cousins. She makes money by peeling garlic for a nearby restaurant. Then one evening, after an encounter with a homeless woman, she’s struck by lightning. And begins to see her teen self (Park Hye-jin), touching off flashbacks to her youth — even as she meets and enters into a tenuous relationship with a new man in her life, Juh-wang (Hong Sang-pyo). And further change looms: the owner of the house where she lives wants to sell it.

Who those owners are and why they’re selling and what this means for Chun-hee are things revealed in the story as it unfolds. What is important to know is that Chun-hee suffers from a disease where she sweats excessively, thus leaving a trail like a slug. This, along with the death of her parents, led to neglect during her teens, whether from her family or teachers. The result of that is an adult life lacking drive or movement, a mental paralysis events force her to overcome.

We see the events in her past that caused an invisible long-term trauma, and so come to understand her situation in the present. The film is a character piece with some lightly fantastic elements that justify the story’s specific form, and the way the past and the present unfold together. As such it’s effective. There is even considerable elegance in the way what we are told at different points in the story shape what we understand when. In particular, Chun-hee’s relationship with her cousins is given a sneaky power, as moments of understanding dawn on us.

The story otherwise avoids flashy or melodramatic moments, so that for Chun-hee herself things move forward with relative simplicity. The appearance of her past self doesn’t come to much dramatically; it doesn’t really turn into a focus of the movie. Instead, for Chun-hee, this is a story about what to do in her life. The ending is relatively upbeat, if symbolically so. Almost by default this is a story of healing, then, and as such it’s relatively credible.

In general, this is a quiet story that lives in its moments of intense observation. A woman cleaning a wooden floor. A shared meal. A pair of running shoes. The quiet of most of the story is shattered in a couple of devastating moments in which things we have seen repressed finally come out; and there are moments of violence, physical and emotional. But this is a story more of aftermaths than of conflicts or even of choices. In a sense, this is a movie about Chun-hee reaching a point where she can make a choice, or at least knowingly choose not to choose.

In general, this is a quiet story that lives in its moments of intense observation. A woman cleaning a wooden floor. A shared meal. A pair of running shoes. The quiet of most of the story is shattered in a couple of devastating moments in which things we have seen repressed finally come out; and there are moments of violence, physical and emotional. But this is a story more of aftermaths than of conflicts or even of choices. In a sense, this is a movie about Chun-hee reaching a point where she can make a choice, or at least knowingly choose not to choose.

Visually, the camerawork reflects Chun-hee’s nature. Camera moves are rare, with the story unfolding mainly through still shots. This is a useful way to represent the passivity and lack of movement of the character. Just as the individual pictures are well-composed but static, so does Chun-hee’s apparent composure mask an overall inertia.

Along with that, I note that the film does a strong job depicting architecture, specifically of the house that means so much to Chun-hee. The room she was given as a youth is a tiny narrow attic room, both cell and also sanctuary. That ambiguity seems to echo throughout the house as a whole. It’s shelter for her, but also a place of self-imprisonment. It’s a place of memory and the past, as vivid as the present, and it’s no surprise when that past comes alive.

Along with that, I note that the film does a strong job depicting architecture, specifically of the house that means so much to Chun-hee. The room she was given as a youth is a tiny narrow attic room, both cell and also sanctuary. That ambiguity seems to echo throughout the house as a whole. It’s shelter for her, but also a place of self-imprisonment. It’s a place of memory and the past, as vivid as the present, and it’s no surprise when that past comes alive.

The place is not shown as labyrinth; this is not a puzzle film hiding a mystery, and the flashback structure never forces us to radically reinterpret what we thought we knew. It does occasionally give us a sense of the passage of the years, a sense of stepping back from the story to see the whole sweep of time in people’s lives. And in general the structure works well enough that the flashbacks don’t seem to be slowing the present-day story down, a tricky thing to manage. The past is used well, in other words, even if the idea of Chun-hee dealing with her younger self is relatively underplayed.

This is a kind of arthouse genre story, a tale of a character which gains some of its effect by the inclusion of a nominally genre-based plot point. But that plot point is not in itself the central point of the film. The mechanics of what happens to Chun-hee when she’s struck by lightning are not important. The story’s about who she is and how she grows, and the movie itself is clear on that point.

This is a kind of arthouse genre story, a tale of a character which gains some of its effect by the inclusion of a nominally genre-based plot point. But that plot point is not in itself the central point of the film. The mechanics of what happens to Chun-hee when she’s struck by lightning are not important. The story’s about who she is and how she grows, and the movie itself is clear on that point.

It’s worth pointing out that this fundamentally serious tale about a woman repressing her trauma is balanced by a comic love story. Kang Jin-ah does excellent work in conveying the subtleties of Chun-hee’s emotions, but Hong Sang-pyo does a fine job playing off that to create a credible and sympathetic love interest. You believe in their relationship, and hope that things work out; that these people can find a way to be together.

The Slug played Fantasia as part of the festival’s Camera Lucida section, movies that use genre elements in unconventional ways. That’s certainly the case here. Viewed in the context of a genre film festival, it feels like a genre film, with the charge of weirdness that genre gives a story. Outside of that context, I wonder how it would be perceived; its concerns are all of this world. There is perhaps a tension in it between the mainstream aspect of a character-based story of emotional trauma on one hand and on the other a story of a woman with a peculiar physiological disorder struck by lightning and faced with a curious kind of timeslip. The fact that the second things exist to shed light on the first doesn’t take away from the fact that they do exist, and give a flavour to the movie, a kind of absurdity, an undermining of what is certain. And create a way by which fixed certainties of behaviour can change. This is a character-centred movie about Chun-hee’s life, to be sure, but in the end the possibility of her healing comes about only through the fantastic.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.