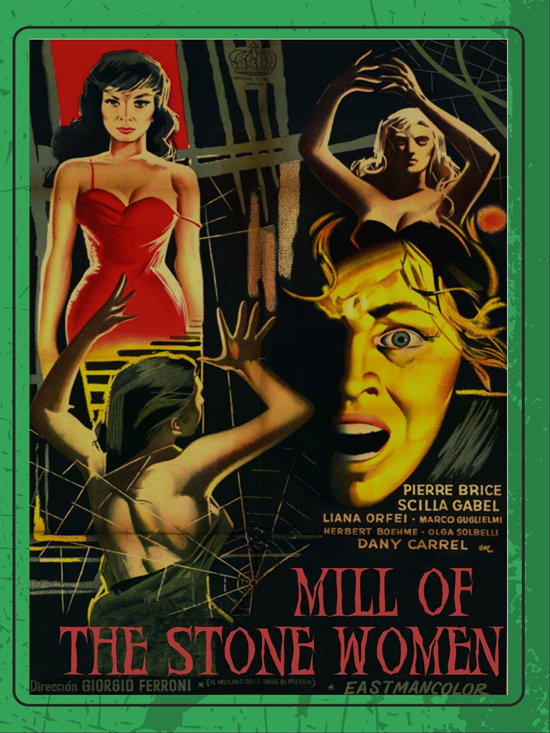

Fantasia 2021, Part XXXIII: Mill of the Stone Women

Directed by Giorgio Ferroni, Mill of the Stone Women (Il mulino delle donne di pietra) was released in 1960. The first colour Italian horror film, its striking hues would influence Mario Bava in 1964’s Blood and Black Lace, and through him the emerging giallo genre. Arrow Video’s restored the film to its full original lushness, and the Fantasia Film Festiva screened the restoration. I was fascinated by the film’s imagery and tone; Mill captures a colourful gothic sensibility that echoes early Hammer Studios productions, a classic movie gothic that implies a world in which all sorts of horrors and monsters may exist.

Directed by Giorgio Ferroni, Mill of the Stone Women (Il mulino delle donne di pietra) was released in 1960. The first colour Italian horror film, its striking hues would influence Mario Bava in 1964’s Blood and Black Lace, and through him the emerging giallo genre. Arrow Video’s restored the film to its full original lushness, and the Fantasia Film Festiva screened the restoration. I was fascinated by the film’s imagery and tone; Mill captures a colourful gothic sensibility that echoes early Hammer Studios productions, a classic movie gothic that implies a world in which all sorts of horrors and monsters may exist.

(The writing credit for the film involves its own bit of gothic misdirection. Ferroni was involved in reworking a script by Remigio Del Grosso, Ugo Liberatore, and Giorgio Stegani, and the onscreen credits claim the film was based on a tale by Pieter van Weigen in his book Flemish Tales. But in fact there is no writer named Pieter van Weigen, and no book by him named Flemish Tales. Early gothic novels often used the device of false attributions to some nonexistent source — look at Horace Walpole’s Castle of Otranto, which he originally claimed to be a medieval manuscript — and it’s amusing to see that game played here, a couple hundred years later in a different artform.)

Mill brings us an involved story set around the turn of the twentieth century. It follows a writer, Hans von Arnim (Pierre Brice), who travels to the well-known Mill of the Stone Women to write an article about the Mill’s pageant of lifelike statues, the stone women, put on display by the mysterious Professor Gregorius Wahl (Herbert A.E. Böhme). At the mill, Hans finds several mysteries, among them the professor’s beautiful daughter Elfie (Scilla Gabel) who is attended by her own live-in doctor, Loren Bohlem (Wolfgang Preiss). Hans is drawn to Elfie, and begins to uncover the secrets of the mill, putting himself in terrible danger.

The movie’s powerfully atmospheric, and the restoration brings out the richness of its colours from the very first scene, as Hans arrives at the mill on a misty river. Beyond the colour work, this generally a fine visual piece of work, with striking compositions and good dramatic lighting. Nighttime shots of the mill emphasise its eerieness and build it as a location. The overall gothic sense of place is very strong: the small garret where Hans writes his piece, the lushness of Elfie’s bedchamber, the machinery that moves the statues across the stage.

In fact the pageant feels like it’s somehow a metaphor for the film as a whole: creaking machinery drives a plot relentlessly but at a fixed pace. This is not always a bad thing; there’s nothing self-indulgent here, and while the visuals of the film are atmospheric, the movie doesn’t dwell on them. The atmosphere inflects the story, which is told directly. Dialogue’s expository, though not excessively so. Acting choices are broad, though never quite hammy. Shot choices emphasise clear storytelling; there’s a classical feel to the film, the sense of a traditional gothic horror movie, as though Vincent Price might wander out from behind the scenery at any moment.

There are a number of strands to the story, including Hans’ friends at art school and the mysterious disappearances of local women, so it’s not wrong for the film to put a premium on clarity. Certainly there’s an extravagance to the gothic furniture here: a pageant of statues, a mysterious professor, a creaking shadowed mill, later a secret laboratory. A beautiful girl with an enigmatic illness. An everyday man who journeys to a place he does not know and finds himself caught up in horror. Hallucinations. A faked death. It’s played too straight to be camp, but the film does seem to enjoy exploring the terrain of the gothic tale.

There are a number of strands to the story, including Hans’ friends at art school and the mysterious disappearances of local women, so it’s not wrong for the film to put a premium on clarity. Certainly there’s an extravagance to the gothic furniture here: a pageant of statues, a mysterious professor, a creaking shadowed mill, later a secret laboratory. A beautiful girl with an enigmatic illness. An everyday man who journeys to a place he does not know and finds himself caught up in horror. Hallucinations. A faked death. It’s played too straight to be camp, but the film does seem to enjoy exploring the terrain of the gothic tale.

Unfortunately, it does this with a curious lethargy. The pacing’s too measured, the story clear but plodding. There is an explosive climax that works well, but much of the film’s vitality is sapped by the extensive subplots. The story’s muted at points where it could have used a jolt, and even the romance elements are poorly served by the lack of energy.

This is especially a problem when the stately pace of the film undermines an attempted gaslighting of the protagonist. Done right you can see how the story at this point could have caused viewers to question what we thought we understood about reality, or at least about the film’s reality. This doesn’t happen, because the thing moves so slowly we can work out what’s happening. It’s more interesting to note the attempt at the twist, and ponder how it would be done better in the giallo films that would come in later years.

It’s also interesting to see the movie mix gothic tropes. There’s some echoes of Universal’s Frankenstein movies in the way traditional gothic architecture meets the imagery of scientific labs and a concern with blood types. There’s the feeling of something supernatural ever on the verge of happening, particularly strong in a scene involving a night vigil in a cemetery, but that ends up manifesting in the uncanny mysteries of science. The gothic science the movie gives us is what happens when the idea of science is married to the gothic’s fascination with the dreamlike and the irrational — a kind of mad science, a weird science, a science that is very much in the lineage of Victor Frankenstein.

It’s also interesting to see the movie mix gothic tropes. There’s some echoes of Universal’s Frankenstein movies in the way traditional gothic architecture meets the imagery of scientific labs and a concern with blood types. There’s the feeling of something supernatural ever on the verge of happening, particularly strong in a scene involving a night vigil in a cemetery, but that ends up manifesting in the uncanny mysteries of science. The gothic science the movie gives us is what happens when the idea of science is married to the gothic’s fascination with the dreamlike and the irrational — a kind of mad science, a weird science, a science that is very much in the lineage of Victor Frankenstein.

It’s all spooky enough in a measured, classic way. It’s not particularly tense or thrilling, but it does what it wants to do. Despite breaking ground in its use of colour, Mill Of the Stone Women is a very classical kind of a horror film, a film from just before the 60s blew the doors off all the old conventions and set new bounds on what could and could not be shown. (There is in fact some nudity in this movie, but no real blood.) Surprisingly, the stone women themselves play only a minor part, although their mill is indeed front and centre throughout. Like the mill, the film moves things along slowly — but it’s reliable, and if the mechanism’s creaky that’s part of the fun. And there are secrets hidden in its unexplored crannies. In all it’s a solid bit of entertainment in its genre, and a good bit of business to take in to prepare for the Halloween season.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.