Fantasia 2021, Part XXXII: The Spine Of Night

“Death and the Winemaker” (“Le Vigneron et la Mort”) is a 19-minute French-language animated film from Switzerland written and directed by Victor Jaquier. It’s a folkloric tale about a winemaker (voiced by Kacey Mottet Klein) in a Renaissancelike land who tries to win the heart of a noble young lady (Marie-Claire Dubois) by crafting the best wine in the world. But things take a turn when Death (Virginie Meisterhans) is drawn to the perfection of the winemaker’s creation. The story’s a nice rich tale of unwanted consequences, but what makes it work are the 2D visuals. The film recalls classic Disney movies in its designs, but is darker and naratively much richer. The castle in which the beautiful maiden dwells with her tyrannical father is detailed and charming, the winemaker’s town is intricate and gothic, the characters are cartoony and evocative. It’s good work for all ages.

“Death and the Winemaker” (“Le Vigneron et la Mort”) is a 19-minute French-language animated film from Switzerland written and directed by Victor Jaquier. It’s a folkloric tale about a winemaker (voiced by Kacey Mottet Klein) in a Renaissancelike land who tries to win the heart of a noble young lady (Marie-Claire Dubois) by crafting the best wine in the world. But things take a turn when Death (Virginie Meisterhans) is drawn to the perfection of the winemaker’s creation. The story’s a nice rich tale of unwanted consequences, but what makes it work are the 2D visuals. The film recalls classic Disney movies in its designs, but is darker and naratively much richer. The castle in which the beautiful maiden dwells with her tyrannical father is detailed and charming, the winemaker’s town is intricate and gothic, the characters are cartoony and evocative. It’s good work for all ages.

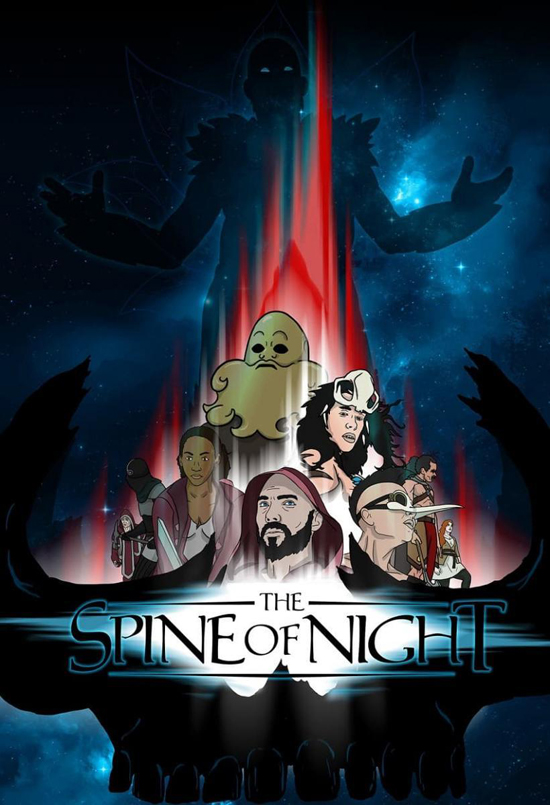

The feature film it was bundled with was the movie I’d been most eagerly looking forward to at Fantasia, and it did not disappoint. The Spine of Night, written and directed by the team of Morgan Galen King and Philip Gelatt, is billed as a feature-length animated sword-and-sorcery film for adults in the vein of the Heavy Metal movie. And it very much is that. It’s more serious than Heavy Metal in many ways, but the violence and cosmic scope is if anything even greater.

It begins with a starscape, and then drops to a planet’s surface where a nearly-nude woman (voiced by Lucy Lawless) in a garland of odd blue flowers struggles up a mountainside to reach an armoured figure (Richard E. Grant). She begins to tell him stories, and we watch these stories play out, with all their brutality and violence and magic and wonder; they are stories about the past, her and her people’s stories, and they cover vast spans of time and do not take the sort of shape you might expect. There is a point where the guardian tells her a story of his own in return. And when all these tales are done, we will have seen the rise and fall of civilisations, and will understand who she is and who he is and why she came to him and what the meaning of the flowers are. And then, of course, there will be a final confrontation that we’ll only understand because of the stories we’ll have seen.

In getting to that point we see the witchery of a swamp-dwelling tribe, see twisted industrial airships, see secret societies of scholars with adventurers who plunder lost tomes. We see a war against gods. We see mad wizards and twisted rituals. We see slaughter and moments of tenderness. We see despair, and also the perseverance of life.

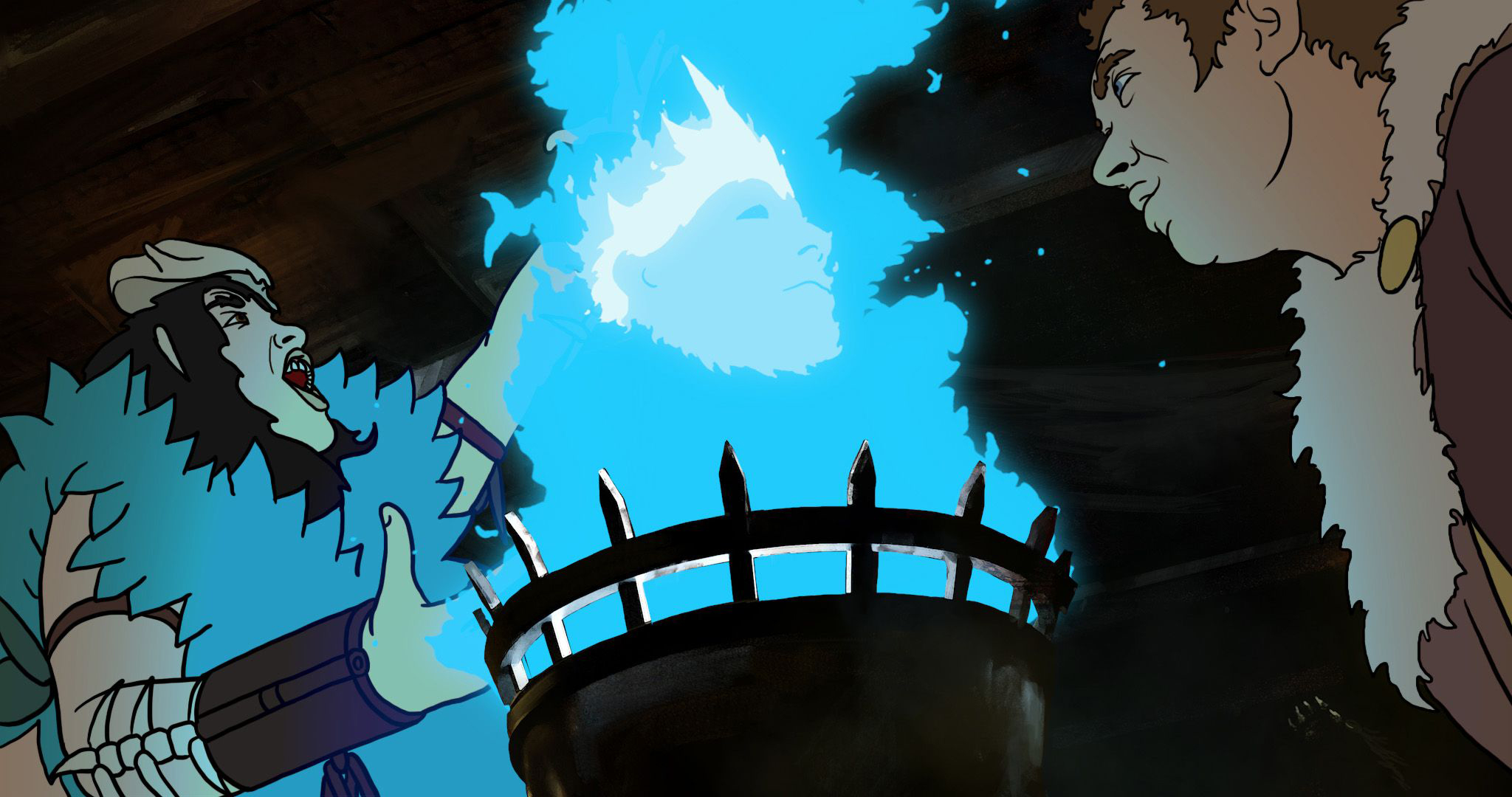

And we see all this in 2D animation with rich organic linework and rotoscoped figures. Characters move and emote in unanimelike ways against painted backgrounds. The film was made with a small crew of a few animators, but they did the work of dozens: the film looks spectacular. It’s different from something like Heavy Metal or Ralph Bakshi’s Fire & Ice in its colour work — rather than bright contrasting colours, The Spine of Night uses a lot of complementary tones. If the older films looked like four-comics of their era, this one has the colour sensibility of a contemporary comic, less spectacular in some ways but perhaps with more depth.

And we see all this in 2D animation with rich organic linework and rotoscoped figures. Characters move and emote in unanimelike ways against painted backgrounds. The film was made with a small crew of a few animators, but they did the work of dozens: the film looks spectacular. It’s different from something like Heavy Metal or Ralph Bakshi’s Fire & Ice in its colour work — rather than bright contrasting colours, The Spine of Night uses a lot of complementary tones. If the older films looked like four-comics of their era, this one has the colour sensibility of a contemporary comic, less spectacular in some ways but perhaps with more depth.

The designs are less idealised, too. It’s not that there aren’t physically imposing and powerful characters, but they tend to look like actual athletes. And like products of a leaner world with less constant food supplies: slim and wiry. Notably unlike Heavy Metal, women look like people with actual proportions. There’s a reduction in sexuality that helps to sell the violence: without the idealisation, there’s a gain in physicality. You believe you’re looking at actual humans stabbing and being stabbed.

Backgrounds are detailed and distinctive. There’s a clear influence of European history in the stone castles and medieval towns we see, but also individual flourishes that set this world apart from the world we know. As history moves along and we come to a dystopic industrial landscape we see wholly new things, not quite alien but the familiar made unfamiliar.

Backgrounds are detailed and distinctive. There’s a clear influence of European history in the stone castles and medieval towns we see, but also individual flourishes that set this world apart from the world we know. As history moves along and we come to a dystopic industrial landscape we see wholly new things, not quite alien but the familiar made unfamiliar.

And indeed the movie becomes more epic as we move along. As history accretes with each story, we get a deeper sense of the sweep of the film. The scale becomes greater as we follow themes across ages. On a basic level, each tale gives us new things to look at. But the way they fit together and build on each other shapes the whole. The tale of the guardian is especially useful here, introducing a new visual style and a mythic substrate to all the human wars we’ve seen. It acts something like a bridge or middle eight in a song, adding contrast and broadening the themes introduced thus far.

The Spine of Night uses this grand scale to introduce grand ideas. It doesn’t try to explore philosophical concepts in detail, but uses its scope to present a myth of cosmic nihilism, considering the idea of meaning and the difficulty of finding meaning within a vast universe haunted by absent gods. The blue flowers that are a recurring motif in the film (shades of Heavy Metal’s Loc-Nar, but with more thematic definition) also point to concerns beyond the sweep of time, a link to the divine — but, one is made to wonder, to what sort of the divine? I don’t know whether the movie qualifies as what is traditionally called ‘profound,’ but I find myself returning again and again to the word ‘cosmic.’ There’s a scope here that satisifies.

The Spine of Night uses this grand scale to introduce grand ideas. It doesn’t try to explore philosophical concepts in detail, but uses its scope to present a myth of cosmic nihilism, considering the idea of meaning and the difficulty of finding meaning within a vast universe haunted by absent gods. The blue flowers that are a recurring motif in the film (shades of Heavy Metal’s Loc-Nar, but with more thematic definition) also point to concerns beyond the sweep of time, a link to the divine — but, one is made to wonder, to what sort of the divine? I don’t know whether the movie qualifies as what is traditionally called ‘profound,’ but I find myself returning again and again to the word ‘cosmic.’ There’s a scope here that satisifies.

In a fine question-and-answer session on Fantasia’s YouTube channel, the filmmakers cited Walter M. Miller’s A Canticle For Leibowitz as inspiration for their work. You can see it clearly: the movement across eras of a civilisation, the sense of cycles of history, the search for some divine meaning in the patterns of human events. Of course the approach here is different in a number of ways, but the depiction of great abysses of time echoes Miller’s novel. Beyond Leibowitz I also felt there was some similarity to the fiction of Clark Ashton Smith at his least ironic and most morbid. There’s a taste at least of his decadence, his depiction of faraway times and worlds as just as fallen as this one. And there is a sort of dying-earth feel (a bit like Jack Vance, but more like Smith’s Zothique tales) to the history we see: familiar, with echoes of archetypes we know, but distinct and terrible.

The Spine of Night is a movie that succeeds admirably at what it wants to do. It’s the most essential film for sword-and-sorcery fans I’ve seen in years. It starts on a slow scale, and builds superbly as it moves along through different stages of civilisation with extreme violence. It evokes the psychedelic art and stories of the 70s without being derivative or woolly-headed; in fact, the movie’s concerned with ultimate meaninglessness in a way that feels like a powerful rewriting of earlier cosmic visions. This film is just exactly what it looks like, and exactly what I hoped it would be, and it’s glorious.

The Spine of Night is a movie that succeeds admirably at what it wants to do. It’s the most essential film for sword-and-sorcery fans I’ve seen in years. It starts on a slow scale, and builds superbly as it moves along through different stages of civilisation with extreme violence. It evokes the psychedelic art and stories of the 70s without being derivative or woolly-headed; in fact, the movie’s concerned with ultimate meaninglessness in a way that feels like a powerful rewriting of earlier cosmic visions. This film is just exactly what it looks like, and exactly what I hoped it would be, and it’s glorious.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Was looking forward to The Spine of Night before this article, and now I’m super anxious. Looks like it’s not available online until Oct 29th. Sigh.

Saw The Spine of Night at the recent Sitges Film Festival, and couldn’t agree more with the above review.

[…] (15) AT THE SCREENING. At Black Gate, Matthew David Surridge reviews an interesting-looking animated fantasy film called The Spine of Night: “Fantasia 2021, Part XXXII: The Spine Of Night” […]