Fantasia 2021, Part XXIII: Giving Birth To A Butterfly

“MonsterDykë” is a four-minute Canadian short directed and written by Kaye Adelaide and Mariel Sharp. It stars Adelaide as a trans sculptress who’s being pestered for a date by a manipulative guy; she hangs up on him and turns to her work-in-progress. At which point the movie turns into an update of the Pygmalion myth. It has an interesting look, shot on back-and-white 16mm film, and is both sweet and explicit. The design of the sculpture’s imaginative, and if the story’s not surprising, at less than five minutes it doesn’t really need to be.

“MonsterDykë” is a four-minute Canadian short directed and written by Kaye Adelaide and Mariel Sharp. It stars Adelaide as a trans sculptress who’s being pestered for a date by a manipulative guy; she hangs up on him and turns to her work-in-progress. At which point the movie turns into an update of the Pygmalion myth. It has an interesting look, shot on back-and-white 16mm film, and is both sweet and explicit. The design of the sculpture’s imaginative, and if the story’s not surprising, at less than five minutes it doesn’t really need to be.

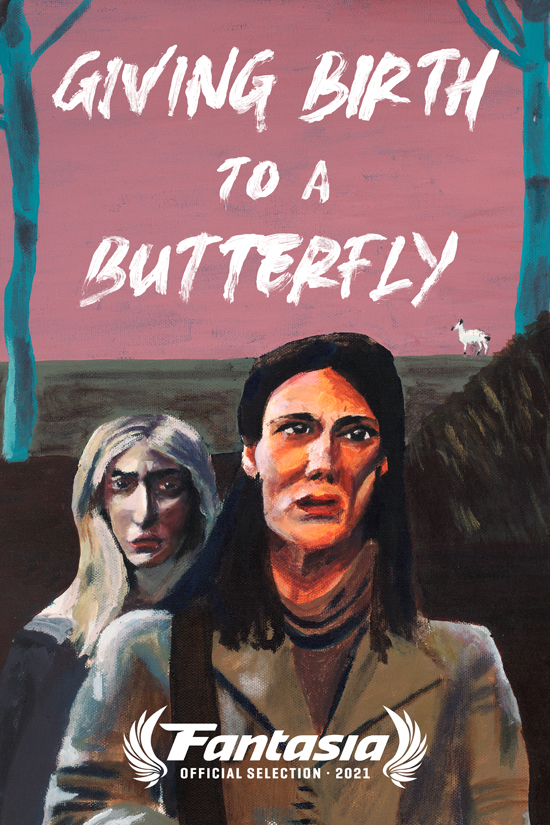

The feature that was bundled with the short was Giving Birth to A Butterfly, which would prove to be one of my pleasant surprises of the 2021 Fantasia Festival. It’s the first film from director Theodore Schafer, who co-wrote it with Patrick Lawler. And it’s a surprising work that seems to change shape as it goes along. The air of surrealism is constant. But the degree of surrealism is not, and what starts at first like a domestic comedy with an odd edge delves into more dreamlike and indeed mythic terrain as the story goes on.

Diana (Annie Parisse) is married to the optimistic but unaccomplished aspiring restauranteur Daryl (Paul Sparks), and is the mother of teens Danielle (Rachel Resheff) and Andrew, AKA Drew (Owen Campbell). Shortly after the movie starts, Drew introduces the family to his new fiancée, Marlene (Gus Birney), who is pregnant and not with with Drew’s child. Diana is not terribly pleased about this situation, but when her identity is stolen she must turn to Marlene to hep her drive to the address of a mysterious company where she hopes to resolve the situation. Meanwhile Danielle’s working backstage on the school play, and Marlene’s mother (Constance Shulman), who sees herself as an actress, is losing touch with reality.

This sounds relatively close to realism; it doesn’t play that way. This is a deeply stylised movie, visually and otherwise. Acting performances are theatrical, with unusual rhythms. Camera moves are unconventional. The aspect ratio as well; the film’s shot on 16mm film, the corners rounded presumably just because the camera’s gate had rounded corners. It’s a movie that looks like a movie.

The writing’s equally stylised, from the opening voice-over that gives the film its peculiar title. Characters speak about dreams and quote Homer and refer to Ibsen. The funny thing is that it doesn’t feel quite unrealistic — it is, but doesn’t feel like it. There’s something here deeper than realism, perhaps something like a dream or something to do with myth, or perhaps something to do with the way in which everyone creates an unreal image of themselves.

One of the main themes of the film is self-image and self-presentation. Daryl sees himself as a restauranteur inevitably heading toward a big break; Diana knows better. Marlene’s mother Monica sees herself as an actress awaiting stardom; Marlene knows better. It’s probably no coincidence that it’s Diana and Marlene who end up travelling together into a deeply strange place. (I note also that the film, driven by its women characters, gives us different kinds and generations of mothers.) But it’s also probably not a coincidence that Danielle is deeply involved with the stage, a strange place of its own. Or that Diana starts the movie selling dresses; what is a dress but a costume, and what is a costume but a statement about who the wearer is or aspires to be? The movie’s awake to the theatricality of life. And to the way we perform our roles, whether in a job, or as part of a family, or to ourselves as we build a self-image that may be more separate from objective truth than we understand.

One of the main themes of the film is self-image and self-presentation. Daryl sees himself as a restauranteur inevitably heading toward a big break; Diana knows better. Marlene’s mother Monica sees herself as an actress awaiting stardom; Marlene knows better. It’s probably no coincidence that it’s Diana and Marlene who end up travelling together into a deeply strange place. (I note also that the film, driven by its women characters, gives us different kinds and generations of mothers.) But it’s also probably not a coincidence that Danielle is deeply involved with the stage, a strange place of its own. Or that Diana starts the movie selling dresses; what is a dress but a costume, and what is a costume but a statement about who the wearer is or aspires to be? The movie’s awake to the theatricality of life. And to the way we perform our roles, whether in a job, or as part of a family, or to ourselves as we build a self-image that may be more separate from objective truth than we understand.

This is also a film haunted by myth. That’s not obvious at first, but it becomes clearer as the film goes on. It means something, I think, that our lead character is named Diana, and that she is hunting down a company named Janus (and finds twins, and the twins have a small image of a door on an end-table that at first is shut and later is open). The image of a lamed white deer recurs, an Arthurian symbol and a symbol that echoes through other mythologies as well; it must be relevant that Diana is a goddess of the hunt. And also that the pet store where Drew works has a fish named Homer.

In general the film makes a heavy use of symbolism, although that doesn’t necessarily become clear until its second half. The first half sets up a number of things that develop almost out of sight, and it is only as they pay off later that we realise the meaning they held. A story Diana tells in the opening minutes of the movie about a pair of dresses returns at the very end. A Wonderland-like house (whose inhabitants hold the kind of gentle surreal wisdom you might find in a Neil Gaiman story) spurs dreams which make clear imagery established earlier but which had not held obvious weight.

In general the film makes a heavy use of symbolism, although that doesn’t necessarily become clear until its second half. The first half sets up a number of things that develop almost out of sight, and it is only as they pay off later that we realise the meaning they held. A story Diana tells in the opening minutes of the movie about a pair of dresses returns at the very end. A Wonderland-like house (whose inhabitants hold the kind of gentle surreal wisdom you might find in a Neil Gaiman story) spurs dreams which make clear imagery established earlier but which had not held obvious weight.

The film comes alive as the relevance of those images becomes clear. If you had asked me halfway through the film, I would have thought it was a watchable movie with some interesting mannered effects. By the end, it became clear what I was watching; not just the meaning of the things I was seeing, but how they meant what they did and the way they brought out meaning. But if the power of the story’s ideas and images are not at first obvious, when they hit they do so with explosive imaginative power.

I note also that the structure of the film’s interesting. The beats of the different acts come about where you’d expect, but don’t take a normal form. It’s a film that wrong-foots you, whether you notice it consciously or not. The blocking’s unusual; editing choices a little odd. It all works, though. It’s technique that’s a bit too invisible to call attention to itself as technique; it just gives you the feeling while viewing that there’s something off that you can’t quite put your finger on.

I note also that the structure of the film’s interesting. The beats of the different acts come about where you’d expect, but don’t take a normal form. It’s a film that wrong-foots you, whether you notice it consciously or not. The blocking’s unusual; editing choices a little odd. It all works, though. It’s technique that’s a bit too invisible to call attention to itself as technique; it just gives you the feeling while viewing that there’s something off that you can’t quite put your finger on.

Again, I think this all has to do with the way the story plays with theatricality and self-image. A hundred years ago when modernists began breaking down the tradition of the Western realist novel they ended up recreating the forms and patterns of Western myth, often consciously turning to myth as a source of imagery. There’s something like that going on here. Characters create their own images of themselves, characters live in their own worlds, and yet also there’s a deeper world of the unconscious and a collective visionary world of myth that the wise among them learn that they cannot deny. This is a rich and strange movie, intelligent and literate and even weirder than it looks on the surface. I’ve written about the way it struck me at one viewing, how what seemed like an oddball domestic comedy slowly turned into something more oneiric. I wonder if I will not see a completely different film if I watch it again. I think this is one of those movies that has that kind of depth: the kind of complex shape that shows you different things every time you look at it. That’s a rare success for a work of art, and something meaningful in itself whatever meaning arises on a given viewing.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.