Fantasia 2021, Part XXI: Ghosting Gloria

“The Last Word” (“Le dernier mot”) is a five-minute-long short film written and directed by Lucas Warin. It starts outside a café: a man (Owen Little) is writing in a notebook, turning over phrases as he works on a story. He appears to discover a bizarre power; but appearances can be deceiving. This is a fun piece about the relation between writer and text, and the ability of writing to conjure a character, if only in the writer’s head. And about whether we really get to write our own stories.

“The Last Word” (“Le dernier mot”) is a five-minute-long short film written and directed by Lucas Warin. It starts outside a café: a man (Owen Little) is writing in a notebook, turning over phrases as he works on a story. He appears to discover a bizarre power; but appearances can be deceiving. This is a fun piece about the relation between writer and text, and the ability of writing to conjure a character, if only in the writer’s head. And about whether we really get to write our own stories.

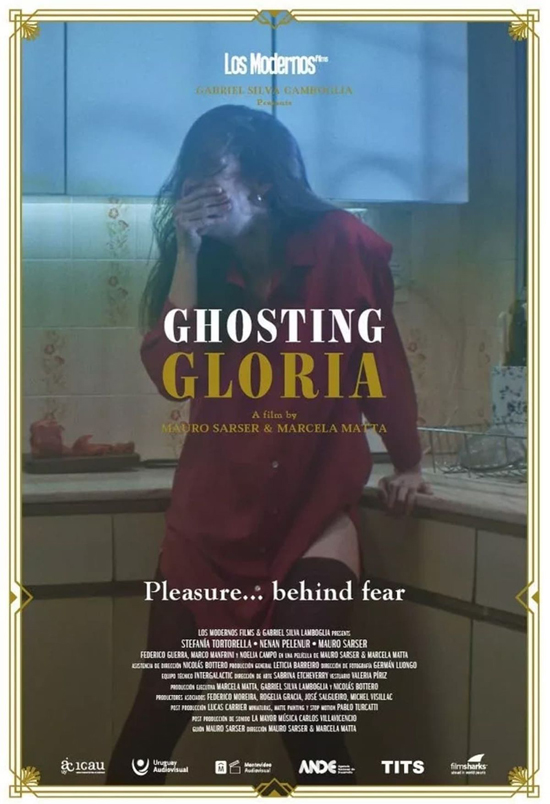

The short was bundled with Ghosting Gloria (Muerto con Gloria), directed by Marcela Matta and Mauro Sarser; Sarser’s credited with the script, though it seems both worked on the story during the making of the film. The translation of the title’s a little odd, as Gloria (Stefanía Tortorella) isn’t ghosted in the usual sense. In fact, something of the reverse.

Gloria’s thirty years old, single, has never had an orgasm, and has more or less given up on relationships. Then she moves into a new house, where a man (Federico Guerra) recently died. His ghost remains, and Gloria begins an enthusiastically sexual relationship with the ghost. She experiments wildly; soon finds herself happier than she’s ever been; and her friend Sandra (Nenan Pelenur), a fellow employee at the bookstore where she works, notices her change of mood. But can the living and the dead maintain a healthy relationship?

One of the problems with the film is that the answer’s clear from early on. But there are other issues. To start with, the invisible ghost introduces himself to Gloria by giving her oral sex, to which she’s had no chance to consent. She enjoys the experience and this launches their idyllic relationship. Two problems follow from this. First, given the tone the movie’s shooting for the rest of the way, the nonconsensual sex act is wildly off-register. Second, you can’t help but suspect that in this scene the ghost’s meant to be a symbol more than a reality — a symbol of Gloria’s desires, and of some autoerotic kind of fantasy. This in turn is a problem firstly because the movie eventually gives us enough objective imagery that it becomes clear that the ghost is meant to be taken as real within the world of the story, and thus while the symbolic aspect is still there it is also clear we have in fact seen a woman raped by a ghost.

Secondly, the movie doesn’t really gain anything if the ghost is purely symbolic. If this is a story about a woman who’s convinced herself she’s haunted as a way of resolving partially-conscious sexual desires, I would say it’s less interesting than a story about a woman finding the same resolution symbolically through interacting with a ghost. I think the unknown of the ghost, the mystery of it, gives the symbol more force than if the ghost is merely a delusion — the story loses nothing if the ghost’s real, and gains much. The movie itself seems to agree, given certain aspects of the ending.

I should note at this point that as an asexual I am clearly not the ideal viewer of this film. It’s very much a sex comedy, though without much nudity or actual onscreen sex. Still, if the subject of a story’s outside the sphere of my interests, a good story will nevertheless pull me in. A comedy ought to be funny, whatever it’s about. And I can’t say Ghosting Gloria succeeded as comedy or story.

I should note at this point that as an asexual I am clearly not the ideal viewer of this film. It’s very much a sex comedy, though without much nudity or actual onscreen sex. Still, if the subject of a story’s outside the sphere of my interests, a good story will nevertheless pull me in. A comedy ought to be funny, whatever it’s about. And I can’t say Ghosting Gloria succeeded as comedy or story.

It’s competent in terms of plot, and the timing of the gags are solid enough. But both are very obvious. The development of the story goes exactly where you expect it go, and ends just about where you’d expect: with Gloria in a standard monogamous heterosexual marriage with a baby on the way. Any hint of subversiveness is abandoned by the conclusion, then, which is not merely conventional in narrative terms but social ones.

What interested me in the movie in the first place was the hint of a literary angle. Gloria’s work in a bookstore promised the opportunity for a series of allusions and references and jokes about writers. There isn’t much of that, though. Instead it gives rise to a series of gags about customers — people who want books with covers of a certain colour to match their wallpaper, that sort of thing. Again, obvious jokes, and not a patch on the stories you’ll hear from actual bookstore owners and employees.

What interested me in the movie in the first place was the hint of a literary angle. Gloria’s work in a bookstore promised the opportunity for a series of allusions and references and jokes about writers. There isn’t much of that, though. Instead it gives rise to a series of gags about customers — people who want books with covers of a certain colour to match their wallpaper, that sort of thing. Again, obvious jokes, and not a patch on the stories you’ll hear from actual bookstore owners and employees.

Still, while the humour’s obvious all the way through the movie, it at least has a sense of visual style. That’s particularly true in its view of Montevideo, and of Gloria’s bookstore. There may not be much interesting playing-about with the world of books in the dialogue, but the location looks lovely. I note also that, according the directors in a (strikingly well-handled) question-and-answer session on Fantasia’s YouTube page, there was no CGI in the film — all the special effects were done practically, with matte paintings and models as needed. That concreteness helps the movie, grounding it in tactile reality.

This is especially true when the film finally goes deep into its idea of the afterlife, developing an interesting myth and spirit world. At that point the practical effects give a sense of the unreality of things; you know the characters are caught up in the unreal among optical tricks, but they’re also literally caught up in the unreal and fantastical so it all works. That spirit world we glimpse is left largely unexplored, which creates a sense of a universe with more going on than just the characters we see. Indeed the last shots of the movie, set up all throughout the film, pay off with a tie-in to the spirit realm that implies more interesting stories than anything we actually get in this movie.

This is especially true when the film finally goes deep into its idea of the afterlife, developing an interesting myth and spirit world. At that point the practical effects give a sense of the unreality of things; you know the characters are caught up in the unreal among optical tricks, but they’re also literally caught up in the unreal and fantastical so it all works. That spirit world we glimpse is left largely unexplored, which creates a sense of a universe with more going on than just the characters we see. Indeed the last shots of the movie, set up all throughout the film, pay off with a tie-in to the spirit realm that implies more interesting stories than anything we actually get in this movie.

It’s worth noting that the film never plays about with horror beyond perhaps a single scene. This is very definitely a sex comedy with fantasy elements, and as such I don’t think it works. The actors do a good job, but the jokes are obvious and the sexuality’s very conventional; relationships pay off just as you expect they will. There are fantasy aspects here that have promise, but aren’t developed. That’s a fair enough choice in the context of what the movie’s trying to do, but given the results, I wonder whether making the visual abandon of the otherworldly sequences more prominent might have led to a better film. Perhaps not; but what’s here doesn’t possess enough of a spark to work.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.