Galloway Gallegher — Kuttner’s Sauced Scientist

|

|

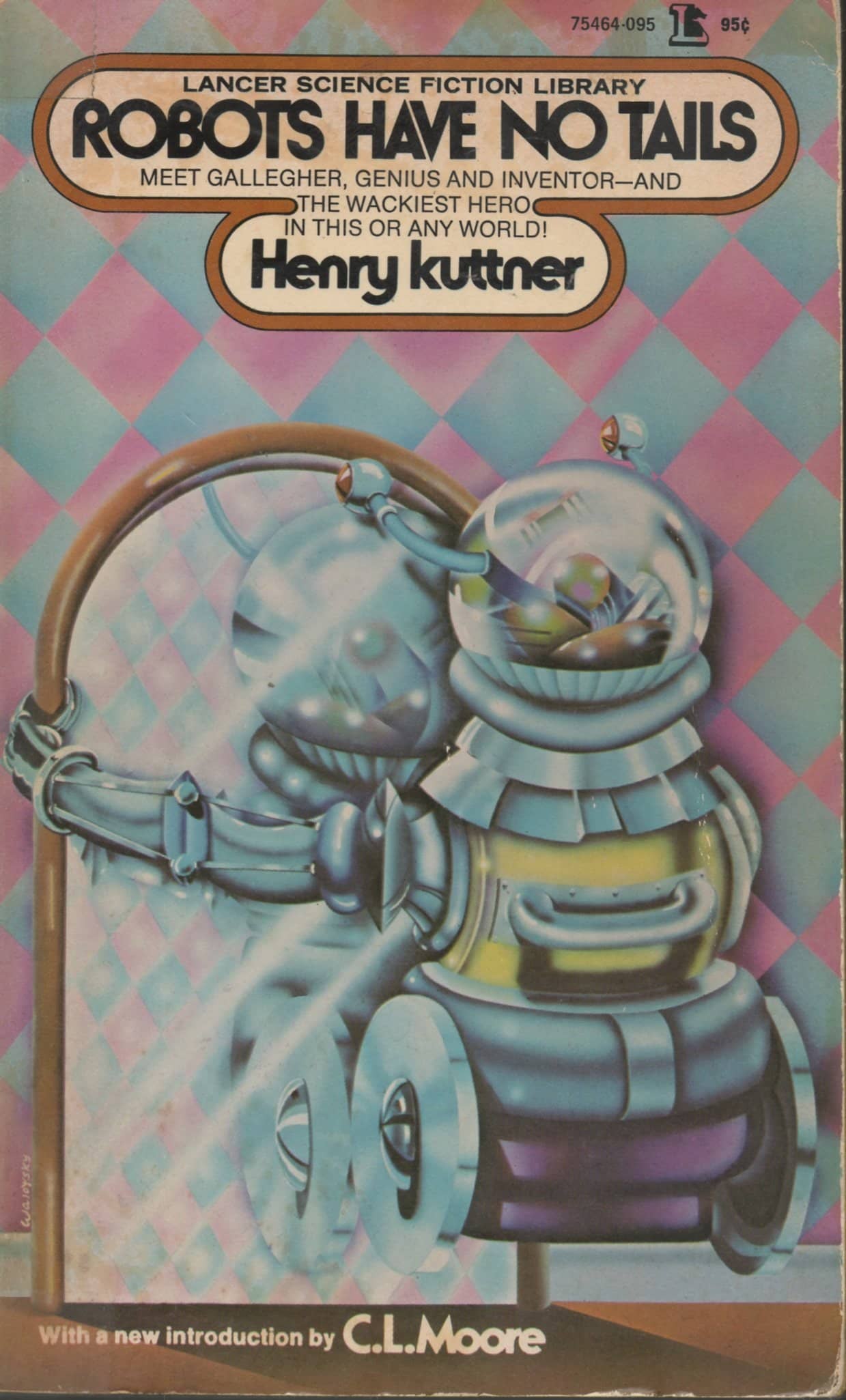

Robots Have No Tails (Lancer, 1973). Cover by Ron Walotsky

Try this one on for size…you go to sleep one night and have a lively dream. You see yourself doing wonderful things, creating new devices based on principles so advanced you can’t even image how they could be. You don’t question the fact that it is a dream because you know that, normally, you could never build such fabulous, world-changing technologies. It’s all kind of fuzzy though — what you’re building, the people you’re interacting with, everything.

When you wake in the morning you discover any number of strange devices in your house. You have no idea what they are, how they work, or where they came from. The phone rings. Apparently, there are several people to whom you now owe a lot money. You’ve never met any of them before but they seem to know you. Is it a scam? You hope so because one of them is suing you for breach of contract. Another is taking you to court for assault and battery. What happened? Could your dreams have been real somehow? Regardless, it seems that you’re now morally responsible for a whole lot of trouble.

This is essentially the premise of Henry Kuttner’s five Galloway/Gallegher stories: “Time Locker” (1943), “The World Is Mine” (1943), “The Proud Robot” (1943), “Gallegher Plus” (1943), and “Ex Machina” (1948).

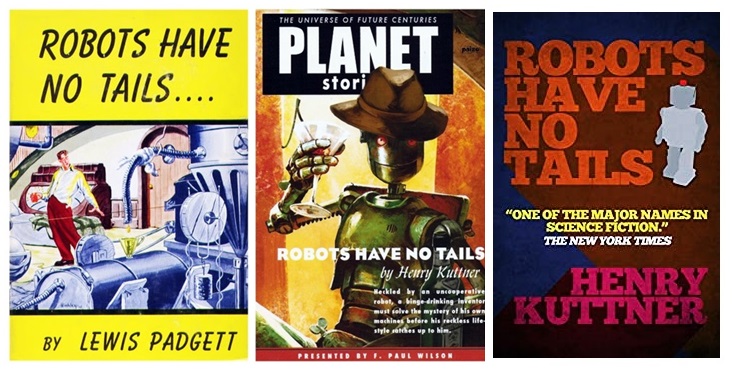

The stories were originally published in Astounding magazine under Kuttner’s Lewis Padgett pseudonym. This name usually indicated that a story was written in collaboration with his wife, Catherine Lucille Moore. However, in the introduction to the Gallagher fix-up (collection), Robots Have No Tails (Gnome Press, 1952), Moore specifically states that she had no hand in these stories, they were all Kuttner’s doing. Observant readers of the original print stories will notice that the protagonist’s name changes from Galloway in “Time Locker” to Gallegher in “The World is Mine.” Why? A rationalization comes from C. L. Moore in her introduction to Robots Have No Tails. The Kuttners had homes on both coasts and “Time Locker” was written on the East Coast. After it was delivered, they drove out to their other home in California. By the time “The World Is Mine” was written, Kuttner had forgotten the character’s original name, re-christening him, Gallegher. This is later explained by his “full” name being — Galloway Gallegher.

Observant readers of the original print stories will notice that the protagonist’s name changes from Galloway in “Time Locker” to Gallegher in “The World is Mine.” Why? A rationalization comes from C. L. Moore in her introduction to Robots Have No Tails. The Kuttners had homes on both coasts and “Time Locker” was written on the East Coast. After it was delivered, they drove out to their other home in California. By the time “The World Is Mine” was written, Kuttner had forgotten the character’s original name, re-christening him, Gallegher. This is later explained by his “full” name being — Galloway Gallegher.

Slip-ups of this sort were more common then you’d think, especially with stories being sold many months before they were scheduled for print. And who types stories for sale with carbons, anyway? I can assure you that most pulp writers did not.

If you read one of the more modern reprints of Robots Have No Tails, you’ll see that editors have corrected “Galloway” to “Gallegher” in Time Locker assuming, correctly, that this makes things easier for readers.

Technically, Gallegher’s job is a 1940’s version of a computer lab supervisor. When he’s drunk — woo boy! He becomes amoral, super-scientist Gallegher-plus. And this alter ego is no alter boy. He’s always getting Gallegher into tricky situations.

Technically, Gallegher’s job is a 1940’s version of a computer lab supervisor. When he’s drunk — woo boy! He becomes amoral, super-scientist Gallegher-plus. And this alter ego is no alter boy. He’s always getting Gallegher into tricky situations.

Gallegher’s always broke and willing to take a client’s money for his next brilliant invention (which he can only create when he’s blotto.) To help open the door to his virtuoso alter-ego, Gallegher builds a “liquor organ” in his lab. He reclines on a comfortably padded couch and, by manipulating buttons, siphon drinks of “marvelous quantity, quality, and variety down his scarified throat.” This liquor organ is seen in all the stories and is almost a character in itself.

There’s no doubt that Gallegher-plus is as brilliant as he is amoral. He is pure creativity and the only things that seems to interest him are tinkering and solving science puzzles. Of course, when he sobers up, Gallegher remembers little from his binges, certainly not how any of the amazing gadgets were constructed (or work) and often, who his clients are.

In “The Proud Robot” Gallegher-plus creates a transparent, narcissistic robot named Joe. Joe is a wonderful foil for Gallegher, and more, it turns out he was built for a specific purpose that Gallegher spends most of the story trying to discover. According to Moore (again, from her introduction), she surmises that robot Joe, sober Gallegher, and Gallegher-plus represent “one complete, brilliant, innocently ruthless person split into three parts.”

In “The Proud Robot” Gallegher-plus creates a transparent, narcissistic robot named Joe. Joe is a wonderful foil for Gallegher, and more, it turns out he was built for a specific purpose that Gallegher spends most of the story trying to discover. According to Moore (again, from her introduction), she surmises that robot Joe, sober Gallegher, and Gallegher-plus represent “one complete, brilliant, innocently ruthless person split into three parts.”

Joe represents the Id — which, in Freudian theory, is the part of the unconscious mind representing basic needs and desires. Gallegher-plus stands for the Ego, the part which immediately controls thought and behavior, and is most in touch with external reality. (Hence that part of Gallegher who does the actual work.) Gallegher sober represents the Super Ego, the ethical component of the personality providing the moral standards by which the ego operates. In other words, Gallegher-plus interacts with clients and thinks up the devices, Gallegher sober deals with the moral consequences of his alter-ego’s actions and Joe the robot kibitzes while admiring himself in the mirror.

In the stories, the ticking clock always involves money and legal issues for Gallegher sober, bought about by the actions of his amoral, drunken self. Although contemporary stories wouldn’t dare make fun of an alcoholic, please remember that back in the 1940’s it was okay to do so. In fact, there was much humor brought about by stumbling tipplers. (As an example, see Dashiell Hammett’s “Thin Man” stories.)

The fabulous machines that Gallegher-plus creates are supposed to be well in advance of their time. I noted in a recent re-reading of “Gallegher Plus” that one of his remarkable inventions seems to be a hologram, described four years earlier than its actual creation in 1947. Makes you wonder where Kuttner was getting his ideas from, doesn’t it?

The fabulous machines that Gallegher-plus creates are supposed to be well in advance of their time. I noted in a recent re-reading of “Gallegher Plus” that one of his remarkable inventions seems to be a hologram, described four years earlier than its actual creation in 1947. Makes you wonder where Kuttner was getting his ideas from, doesn’t it?

Here’s how the stories were originally introduced in Astounding.

“Time Locker” by Lewis Padgett (January, 1943) — A useful little gadget. Stick anything in and it shrank to a point where it was invisible and totally concealed — but it would also shrink other things and permit curious sorts of crime—

“The World Is Mine” by Lewis Padgett (June, 1943) — Gallegher, the mad — or at least cockeyed — scientist, got himself in real trouble that time. Corpses — several of them, but all, unpleasantly, his own —kept haunting him. And the Martians he’d accidently brought up out of Time kept insisting, somewhat plaintively, the world was theirs.

“The Proud Robot” by Lewis Padgett (October, 1943) — Gallegher, the mad — or at least pie-eyed — scientist, had produced a remarkable robot. But seemingly useless. It spent its time admiring its unquestionably remarkable, if not beautiful, self. But Gallegher had to find out — but quick! — why he’d made the infernal thing.

“Gallegher Plus” by Lewis Padgett (November, 1943) — Gallegher, as usual, was in a jam. It wasn’t his fault; it was due to Gallegher-plus, the highly successful — if sufficiently high! — other self.

“Ex Machina” by Lewis Padgett (April, 1948) — Gallegher, the Mad Scientist who plays by ear is loose! Worse — from Gallegher’s viewpoint — a “small brown animal” he couldn’t see kept him in a horrid state of sobriety by drinking all his liquor!

The delay between “Gallegher Plus” and “Ex Machina” is explained by Kuttner’s stint in the army. In her introduction, Moore says she wishes there had been additional Gallagher stories and felt that there probably would have been, if not for the war.

The editors of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the October 1952 issue said the following about Robots Have No Tails:

The editors of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction in the October 1952 issue said the following about Robots Have No Tails:

Here is a book that caused these reviewers to chuck objective detachment out the window and emit a loud, partisan ‘Whee!’… Padgett’s position as the one great humorist of science fiction is still unchallenged.

In his December 1952 review of Robots Have No Tails in Astounding, P. Schuyler Miller says:

In these days of the sociological trend in science fiction it is a relief to find occasional stories which are just plain fun — fun to read, and obviously fun to write. When such stories do turn up, it is likely that Henry Kuttner, in the wry guise of Lewis Padgett, is involved….

The review finishes with the following… “Pure entertainment, lavishly supplied.” I couldn’t agree more.

Of course, I’d recommend these delightful stories to science fiction or pulp fans. If you don’t want to spring for the collectible Gnome Press edition you can find a later reprint from Paizo Publishing (2009) or an eBook from Diversion Books (2014). The original issues of Astounding can also be found as digital copies online.

Oh yes… one more thing. The reason for that crazy title, Robots Have No Tails? Apparently, when the publisher asked Kuttner for a book title his mind blanked out. “I can’t think of one,” he said. “Call it anything you like. Call it Robots Have No Tails if you want to.” And they did. True story!

SARA LIGHT-WALLER is a writer, illustrator, and avid pulp and vintage science fiction fan. In 2020, she won the prestigious Cosmos Award for her illustrated space opera story — “Battle at Neptune.” She’s published two illustrated new pulp books — Landscape of Darkness and Anchor: A Strange Tale of Time and is a regular contributor to several pulp blogs. Catch up with her at Lucina Press.

I just checked the Table of Contents for The Best of Henry Kuttner and there are 5 stories in it that date to 1943, including “The Proud Robot” and an actual Padgett collaboration, “All Mimsy Were the Borogroves”. Wow. Some year. No wonder Ms. Moore lamented his enforced break from writing for fighting.

There’s a very interesting mention of Kuttner’s military service in “The John W. Campbell Letters”, a quote you won’t find online for some reason:

“It’s a miracle that Hank Kuttner stayed alive as long as he did; Catherine did a magnificent job of holding that poor guy together. He was invalidated out of the Army as a psychoneurotic, you know; the Army’s mistake was taking him in the first place. How the man achieved as much as he did, with the terrible psychic wounds he’d been given, is a magnificent tribute to what he had innately.”

The Kuttners gradually drifted away from fiction writing around 1950 and started studying psychology; maybe it was therapy for them? Anyway, Henry Kuttner could have avoided military service since he was a married man. It has been speculated that Robert Bloch got married for that very reason (the only negative thing I’ve read about Bloch).

Kuttner’s service started in early 1942. I don’t know when he was discharged, but AFAIK he was never sent overseas, and 1943 was the year Kuttner&Moore (as Lewis Padgett) was the world’s foremost SF writer, so I assume he was out of the army by then.

The Gallagher stories are not among my favourite Kuttner stories; I prefer the more serious (and often cynical) stories of Lewis Padgett. But the robot made me chuckle.

That’s some interesting information about Kuttner.

I liked the Gallagher stories that I read, but I agree that the likes of “Wimsey” are better.

Kuttner is probably my favorite writer from this time period, whether solo or in collaboration with Moore, edging out Leigh Brackett and Ray Bradbury, especially when writing under the Padgett byline. I’ve always enjoyed the Gallegher stories for their madcap humor.

I strongly agree with Keith’s opinion. Kuttner is my favorite writer from this period as well (though Stanley Weinbaum is a close second). Kuttner’s humor is up there with P. G. Wodehouse and Douglas Adams. I occasionally will crack a smile when reading a good humorous work. With Kuttner’s Gallegher stories I usually guffawed out loud!

[…] You can read my article, “Galloway Gallegher — Kuttner’s Sauced Scientist” here. […]

Every time I hear “St James Infirmary” I think of these stories, which I read long ago in my dad’s old sf magazines.

When I first read the story, I hadn’t yet heard the song, so when I finally heard it, I thought of the machine that sang it and of its harried inventor.

I was playing Lous Armstrong on music.YouTube.com. “St James Infirmary” came on. Of course, I thought of the story. I tried to tell my spouse about it, but couldn’t remember the name or author. I finally guessed “Kuttner” as a search term: I was so glad to find this webpage.