Fantasia 2021, Part X: Tin Can

The Fantasia International Film Festival does a good job matching genres when they bundle a short together with a feature. So Tin Can, a feature-length claustrophobic near-future science-fiction film, came with “Death Valley,” an 11-minute tale of a future of environmental devastation; both about isolation and both featuring protagonists isolated from the world. THe short, written and directed by Grace Sloan, follows a woman in the future living in space who is determined to travel to Death Valley on a barren Earth in order to practise yoga as the sun sets, and then go back into space to attend her friend’s New Year’s Eve party. Things do not go as planned. There’s a nice retro feel to the movie, which looks like it was shot on film, and the effects have the bargain-basement feel of an analog era without feeling cheap for the sake of being cheap — rather, they feel cheap for the sake of an aesthetic, which is perfectly fine. The film’s a little opaque, narratively, but at least provides scope for contemplation; I take it as a piece about the clash between a promised future and the never-quite-dying past.

The Fantasia International Film Festival does a good job matching genres when they bundle a short together with a feature. So Tin Can, a feature-length claustrophobic near-future science-fiction film, came with “Death Valley,” an 11-minute tale of a future of environmental devastation; both about isolation and both featuring protagonists isolated from the world. THe short, written and directed by Grace Sloan, follows a woman in the future living in space who is determined to travel to Death Valley on a barren Earth in order to practise yoga as the sun sets, and then go back into space to attend her friend’s New Year’s Eve party. Things do not go as planned. There’s a nice retro feel to the movie, which looks like it was shot on film, and the effects have the bargain-basement feel of an analog era without feeling cheap for the sake of being cheap — rather, they feel cheap for the sake of an aesthetic, which is perfectly fine. The film’s a little opaque, narratively, but at least provides scope for contemplation; I take it as a piece about the clash between a promised future and the never-quite-dying past.

Then came Tin Can, a Canadian science-fiction movie with strong horror overtones. Directed by Seth A. Smith and written by Smith with Darcy Spidle, it takes place in the near future as a pandemic named Coral ravages eastern Canada. One researcher, Fret (Anna Hopkins) thinks she may have a cure, but then she’s kidnapped and finds herself waking up in a suspended animation pod. The movie’s about her slow struggle to get out of the oversized tin can and learn the truth of what’s happened to her; we as viewers slowly find out as she does.

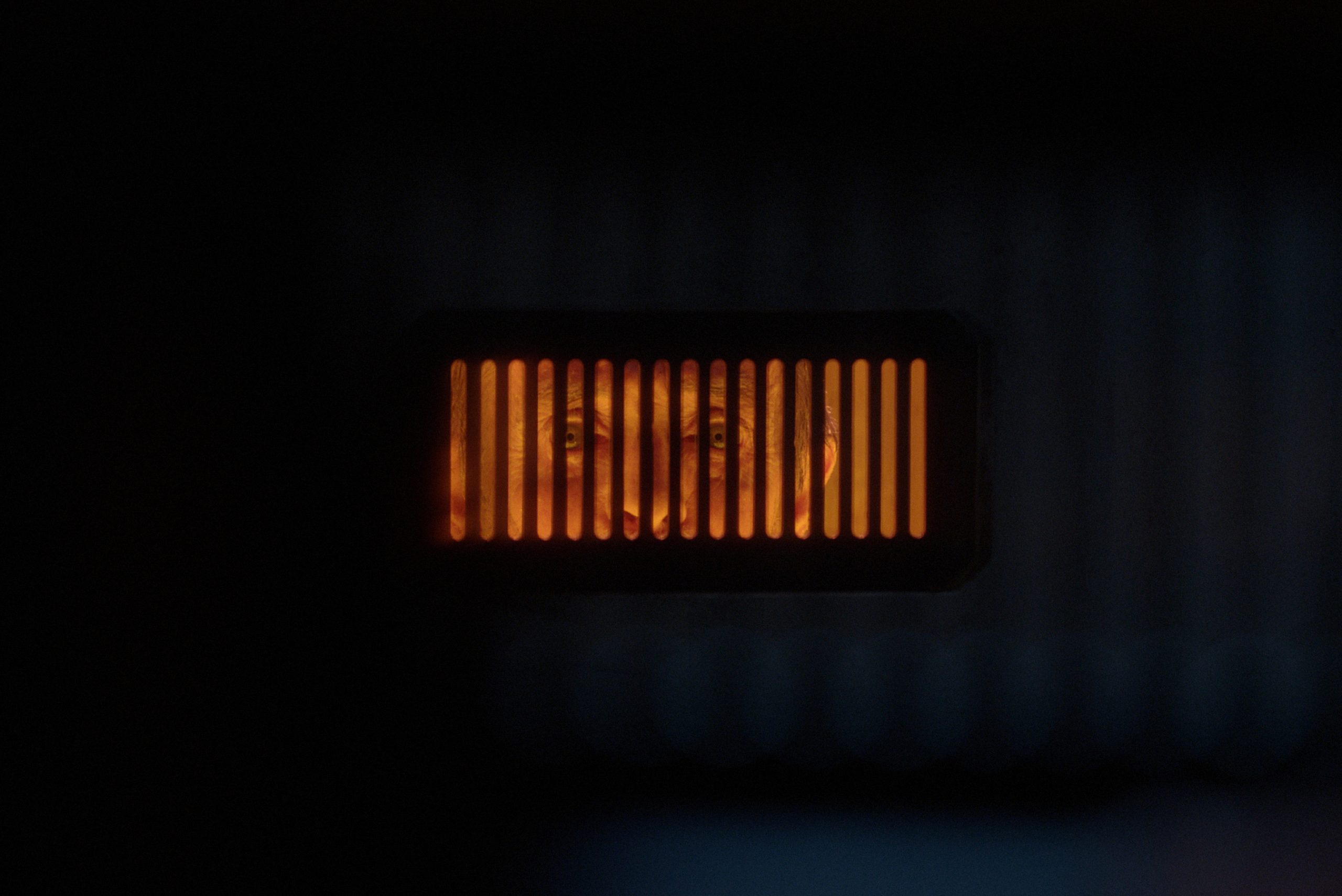

There are two parts to her story (with a brief prologue). The first and longer part follows her within the pod, as she struggles against her environment, and calls out to other people around her in other pods, and from time to time catches glimpses through a vent of mysterious shapes outside. The second part pays off her long agonising struggle to get out. There is a very literal way in which even out of the can, she still carries it with her; but the main thing is that she finds out what is happening, while we as viewers get enough information in the flashbacks to get a sense of the whole picture. The flashbacks work here to inform the present, at one point significantly changing what we thought we understood about Fret, and so feel justified.

(It’s worth noting, incidentally, given the subject matter, that according to a question-and-answer period with Smith and producer Nancy Urich the movie was conceived and shot before the COVID outbreak. The storyline has a lot of odd parallels to present-day reality, and has some topical references to inequality in medical care and the Canadian medical system, but mainly this is a film that is anticipating, not reacting.)

The set-up of Tin Can, one woman alone in a small chamber for much of the film, does not sound like a dynamic viewing experience. But the film makes it work. To start with, Fret is an engaging character; she begins trying to take control of her situation as soon as she wakes up, and that sort of active effort is easy to empathise with. But along with that, the film has a good sense of how much information to dole out when. The movie sets up mysteries for its lead character to solve, and bit by bit she does — not by assembling clues but by dint of constant effort and some intelligence. (It’s more accurate to say that it’s the audience that has to put clues together, but again those are presented at the right rate that the film never feels excessively frustrating.) The information we get is not always what we expect, setting up twists and turns, keeping what could have been a static situation always involving.

The set-up of Tin Can, one woman alone in a small chamber for much of the film, does not sound like a dynamic viewing experience. But the film makes it work. To start with, Fret is an engaging character; she begins trying to take control of her situation as soon as she wakes up, and that sort of active effort is easy to empathise with. But along with that, the film has a good sense of how much information to dole out when. The movie sets up mysteries for its lead character to solve, and bit by bit she does — not by assembling clues but by dint of constant effort and some intelligence. (It’s more accurate to say that it’s the audience that has to put clues together, but again those are presented at the right rate that the film never feels excessively frustrating.) The information we get is not always what we expect, setting up twists and turns, keeping what could have been a static situation always involving.

It helps that Smith comes up with some strong and creative ways to depict the space of the suspended animation pod, starting with a narrow aspect ratio for the film. Rather than restricting our view to Fret’s literal perspective, we often see the pod in cross-section; it’s a powerful device, emphasising how tightly Fret’s bound into a specific area while also suggesting how figuratively thick her sense of imprisonment is. Lighting within and without the pod is used effectively, creating interesting things to look at and varying the interior while also bringing home how little Fret can see outside the pod. It’s also worth noting how much work is done by the voice acting of the performers playing the other people imprisoned near Fret. (One must in particular mention genre veteran Michael Ironside as a cranky old man.)

That’s especially appropriate given the way the movie investigates the theme of connection between human beings. One of the core realities of the suspended animation pod is that it cuts Fret off from other people. She can only hear their voices, which isn’t nothing — and, in fact, it encourages us to take a look at how exactly that’s different from everyday life. There’s a way in which we’re all locked away from other people: locked in our own bodies. Fret’s situation is then in the great science-fictional tradition of literalising metaphors — her situation is reality, seen a different way. (And it may be relevant here that the effect of the disease Coral is to create a solid sheath over an infected person; the physicality of the tin-can prison may also be relevant, as Fret wakes to find plugs and tubes connecting her body to the pod.)

That’s especially appropriate given the way the movie investigates the theme of connection between human beings. One of the core realities of the suspended animation pod is that it cuts Fret off from other people. She can only hear their voices, which isn’t nothing — and, in fact, it encourages us to take a look at how exactly that’s different from everyday life. There’s a way in which we’re all locked away from other people: locked in our own bodies. Fret’s situation is then in the great science-fictional tradition of literalising metaphors — her situation is reality, seen a different way. (And it may be relevant here that the effect of the disease Coral is to create a solid sheath over an infected person; the physicality of the tin-can prison may also be relevant, as Fret wakes to find plugs and tubes connecting her body to the pod.)

If there’s much about human connection, contrariwise there’s also a strong sense of the bleakness of human nature. As we learn, much of what brings Fret to the interior of the pod is a combination of pettinesses, in some cases rising to flagrant disregard for other people. The movie’s about the way in which connection to others is both a strength and a weakness, then, about how we relate as we each project emotions onto each other. By the end we see how the purely mechanical problem of getting out of the pod opens into a broader human situation, which is the sort of thing you want out of this kind of thoughtful science fiction story.

The thriller-mystery structure works, then, and so the movie as a whole works. It is a film that you have to watch more closely than you might at first realise, and sometimes it’s difficult to assimilate the information it gives you. For example, it was a good long way into the movie before I realised the flashbacks were unspooling in reverse order. A second viewing might be needed to catch everything in the film, but it’s thoughtful enough and ambitious enough that a second viewing would be worthwhile.

The thriller-mystery structure works, then, and so the movie as a whole works. It is a film that you have to watch more closely than you might at first realise, and sometimes it’s difficult to assimilate the information it gives you. For example, it was a good long way into the movie before I realised the flashbacks were unspooling in reverse order. A second viewing might be needed to catch everything in the film, but it’s thoughtful enough and ambitious enough that a second viewing would be worthwhile.

This is a smart film that deploys its form intelligently to explore its ideas. Beyond having good science-fictional imagery, it uses that imagery to explore what it is to be human. In particular, it takes the old idea of a suspended-animation pod and gives it a twist, envisioning it as a prison and so presenting a new take on an old genre idea. As cinema the movie tells a story visually in new ways, setting itself unusual constraints and then making use of those constraints to show us new and unexpected things. It can be tough to watch, even if you’re not claustrophobic, but it’s also a bravura work of direction.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.