Fantasia 2021, Part V: Uzumaki

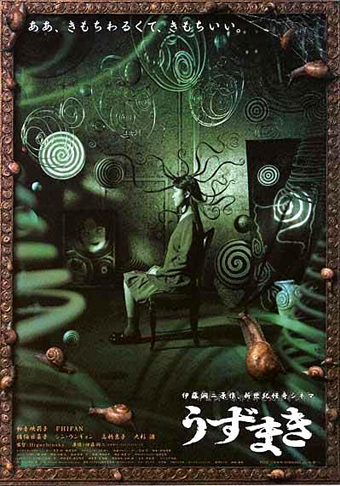

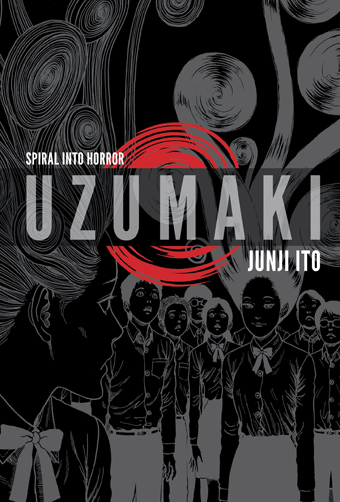

Most of the films at Fantasia 2021 were new, but some were time-honoured works given a screening either because of a new restoration or because they played the festival in the past and were brought back to celebrate Fantasia’s 25th anniversary. Uzumaki (うずまき, literally “Spiral”), from the year 2000, is a case of both — it has a new 4K restoration, and it played Fantasia in 2000. The film’s an adaptation of the manga by Junji Ito, though since it was made while the manga was still ongoing it’s an adaptation that had to find its own answers for some of the questions the text hadn’t resolved at the time of production. Directed by Higuchinsky, AKA Akihiro Higuchi, with a screenplay by Takao Niita, the movie came two years after Ringu (the original version of The Ring) and the same year as the first straight-to-video Ju-On film. It’s one of the early examples of J-horror, then, but sub-genre aside it’s something interesting to consider in its own right.

Most of the films at Fantasia 2021 were new, but some were time-honoured works given a screening either because of a new restoration or because they played the festival in the past and were brought back to celebrate Fantasia’s 25th anniversary. Uzumaki (うずまき, literally “Spiral”), from the year 2000, is a case of both — it has a new 4K restoration, and it played Fantasia in 2000. The film’s an adaptation of the manga by Junji Ito, though since it was made while the manga was still ongoing it’s an adaptation that had to find its own answers for some of the questions the text hadn’t resolved at the time of production. Directed by Higuchinsky, AKA Akihiro Higuchi, with a screenplay by Takao Niita, the movie came two years after Ringu (the original version of The Ring) and the same year as the first straight-to-video Ju-On film. It’s one of the early examples of J-horror, then, but sub-genre aside it’s something interesting to consider in its own right.

The story follows Kirie Goshima (Eriko Hatsune, who would go on to have a role in the live-action Gatchaman), who, like her boyfriend Shuichi Saito (Fhi Fan), is a teen in the small town of Kurouzu-cho. As the movie opens, strange things are happening therein. There’s a mysterious death at the high school. One of Kirie’s classmates has a crush on her and demonstrates this by appearing to her at unexpected times. And Shuichi’s father is growing obsessed with spirals. That last becomes more significant as the film goes on and spirals become increasingly visible through the town — and Mr. Saito’s madness grows worse. And people die. Kirie and Shuichi investigate, desperate to save themselves and the adults close to them and the whole town.

A sense of mystery is strong; indeed it’s what drives the story. And as in a good mystery tale, it’s not that things are completely surreal or obviously inexplicable, it’s that you can almost see what’s happening. Things get stranger as the movie goes on, but Kirie and Shuichi’s reactions give us some human perspective on this increasingly lunatic world of surreal spirals and deranged adults. They have some success in finding out what’s going on, though as in so many horror movies it’s hard to tell what is a clear-eyed look at reality and what is a demented slide into madness. Or indeed if there’s a distinction between the two things.

A sense of mystery is strong; indeed it’s what drives the story. And as in a good mystery tale, it’s not that things are completely surreal or obviously inexplicable, it’s that you can almost see what’s happening. Things get stranger as the movie goes on, but Kirie and Shuichi’s reactions give us some human perspective on this increasingly lunatic world of surreal spirals and deranged adults. They have some success in finding out what’s going on, though as in so many horror movies it’s hard to tell what is a clear-eyed look at reality and what is a demented slide into madness. Or indeed if there’s a distinction between the two things.

Probably the most successful aspect of the film, though, is the visual tone it creates. There’s an emptiness to the movie, a lack of extras and extraneous bodies, that creates a haunting sense of absence. There’s a general dimness, as well, and a green filter over much of the action — enough to feel unnatural. It adds up to a persistent eerieness, a sense of wrongness that cannot be located in any one thing. As the film goes on, CGI is used well to create spirals in the background of shots and sometimes as the manifestation of whatever’s cursing the town; and the movie’s clever enough to take advantage of the uncanny-valley effect of early CGI, letting the unreality of the imagery work to enhance the horror and the feel of the hallucinatory.

As a story, though, the film has its flaws. Too often Kirie and to a lesser extent Shuichi feel extraneous to the action, less implicated observers slowly being reeled in than minor characters given too large a role in the depiction of events. The story builds in a very uneven way, and while some of the things we see have a ghastly surrealism, some (I think particularly of scenes with giant snail-like creatures) are merely ludicrous. Ultimately, the explanation the film offers is unsatisfying because it both explains too much too neatly, and also leaves too many gaps — for example, why the curse on the town (as Shuichi describes it early on) affects certain people before it affects others.

As a story, though, the film has its flaws. Too often Kirie and to a lesser extent Shuichi feel extraneous to the action, less implicated observers slowly being reeled in than minor characters given too large a role in the depiction of events. The story builds in a very uneven way, and while some of the things we see have a ghastly surrealism, some (I think particularly of scenes with giant snail-like creatures) are merely ludicrous. Ultimately, the explanation the film offers is unsatisfying because it both explains too much too neatly, and also leaves too many gaps — for example, why the curse on the town (as Shuichi describes it early on) affects certain people before it affects others.

I have only read the first of the three manga volumes (in Yuji Oniki’s English translation), but much of that first book is visibly present in the movie. A lot of the material’s been restructured to work within the film’s structure, so that, say, individual episodes become running subplots. But the movie captures the uncanniness of the manga, the sense of a real place slowly sliding into the unreal. Kirie’s the viewpoint character in the manga, as well, but the film drops the device of her narration early on, and doesn’t do a particularly good job of finding another way to work her into the action.

Still, the sensation of horror the manga creates is fundamentally the same horror the film presents. It’s the same kind of emotion because it’s not just driven by similar images but by similar themes: obsession, primarily, and to an extent secrecy and history. The story’s about patterns that shape us, whether we perceive them or not, and how perceiving them can be both madness and truth. It is therefore about the horror of being caught up in patterns that fascinate us while being deformed by them. It’s truly Lovecraftian cosmic horror, horror that is about the interference zone between reality and the more-than-real, horror that is about how human identity is shaped by what is not human and perhaps more profound than human.

Which is all very good, but the actual narrative structure leaves something to be desired. The fact that the film was adapting a story that (at the time of adaptation) had no ending is clearly visible; things move too quickly in the last several minutes, suddenly reaching a larger scale that is never explored, while the final scene’s unsatisfying because it is both too small in scale and also resolves nothing of particular value.

I’ve said as well that in the grander scheme of things the surreal is ultimately too much undermined (and reduced) by the logical. Still, the movie works, especially if you ignore the explanations it puts forward. Which is surprisingly easy to do. It’s also better, perhaps, not to look to character growth or development. This is a movie that is at its best in creating a deeply effective atmosphere, and while that usually would be damning with faint praise, it cannot be denied that the film has some brilliant moments — notably, a long take that starts with Kirie delivering a package at night is hypnotic in a near-Lynchian way. I don’t know that this movie is essential viewing. But for fans of the source material, I suspect there’s some value; and for people looking for a distinctive horror sensibility, there is that here.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Haven’t seen this, but I thought the original manga was one of the scariest things I’ve read. Adult Swim is producing an anime adaption that should come out next year.