Once There Were Two Rabbits…Watership Down by Richard Adams

When I was young I watched numerous live-action animal movies on The Wonderful World of Disney (Sunday nights on NBC, right after Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom). There was Run, Cougar, Run (1972), Nikki, Dog of the North (1961), and my favorite, The Incredible Journey (1963). I had, of course, also seen Bambi (1942), an animated movie that gave voice to its animal characters, unlike the live-action ones. The point being, when my friend Karl told me about an exciting book he’d just read about the adventures of rabbits, it sounded like something I’d like. Watership Down (1972) turned out to be nothing like the movies I’d seen and much more than just a book about rabbits.

When I was young I watched numerous live-action animal movies on The Wonderful World of Disney (Sunday nights on NBC, right after Mutual of Omaha’s Wild Kingdom). There was Run, Cougar, Run (1972), Nikki, Dog of the North (1961), and my favorite, The Incredible Journey (1963). I had, of course, also seen Bambi (1942), an animated movie that gave voice to its animal characters, unlike the live-action ones. The point being, when my friend Karl told me about an exciting book he’d just read about the adventures of rabbits, it sounded like something I’d like. Watership Down (1972) turned out to be nothing like the movies I’d seen and much more than just a book about rabbits.

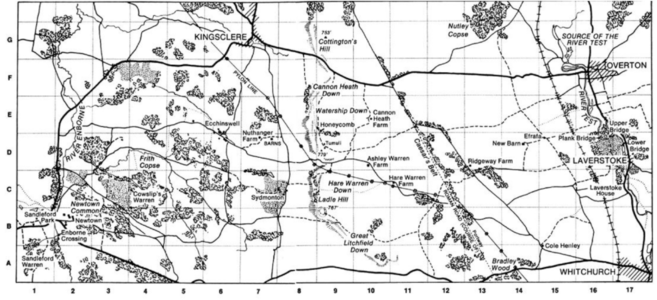

Richard Adams, a British civil servant in the Ministry of Housing and Local Government, created stories to tell his daughters on car rides. He began with the words “Once there were two rabbits called Hazel and Fiver”. The stories were set in and around the real Watership Down, a grass-covered hill in Hampshire, England. It wasn’t long before his daughters insisted he write them down, and in 1966 he started to do just that. After a years-long search for a publisher, Watership Down was released and achieved commercial and critical success, garnering several awards for children’s literature as well.

The bare bones of the novel’s plot are that a band of male rabbits flee their home warren to find a safe place to establish a new one. Along the way, they face adversity in the forms of scarcity, topography, weather, animal predators, and, of course, man. Unlike all those Disney movies, though, Adams wasn’t content to tell a naturalistic story of rabbits in the wild like a lagomorphic version of Tarka the Otter (1927). In the most basic sense, then, Watership Down is not allegorical; Adams repeatedly made that clear. Nonetheless, he dug deep into the sorts of mythic tropes Joseph Campbell explored in works like The Hero with a Thousand Faces (1949)* and the novel is brimming with archetypal elements, e.g. the young man maturing into a hero, self-sacrifice, existential struggles against evil and death. Though devised as a non-allegorical children’s work, Watership Down, informed by Adams’s conservatism and Christianity, addresses some of the deepest issues of humanity and society without ever stooping to didacticism or condescension. Even socialists have discovered great political meaning in the book.

The novel opens on a warm May day with two rabbits of the Sandleford Warren, Hazel, and his small, nervous brother, Fiver, discovering a patch of cowslip then being bullied away from it by members of the Owsla. A footnote informs us that each warren has a body of elite rabbits surrounding its chief. Its nature varies from warren to warren, but in each, it’s called the Owsla. Wandering away from the confrontation, they come upon a recently-placed sign (which they can’t read, let alone comprehend the idea of reading) that practically sends Fiver into a fit:

“Oh, Hazel! This is where it comes from! I know now — something very bad! Some terrible thing — coming closer and closer.”

He began to whimper with fear.

“What sort of thing — what do you mean? I thought you said there was no danger?”

“I don’t know what it is,” answered Fiver wretchedly. “There isn’t any danger here, at this moment. But it’s coming–it’s coming. Oh, Hazel, look! The field! It’s covered with blood!”

“Don’t be silly, it’s only the light of the sunset. Fiver, come on, don’t talk like this, you’re frightening me!”

Fiver sat trembling and crying among the nettles as Hazel tried to reassure him and to find out what it could be that had suddenly driven him beside himself. If he was terrified, why did he not run for safety, as any sensible rabbit would? But Fiver could not explain and only grew more and more distressed. At last Hazel said,

“Fiver, you can’t sit crying here. Anyway, it’s getting dark. We’d better go back to the burrow.”

“Back to the burrow?” whimpered Fiver. “It’ll come there — don’t think it won’t! I tell you, the field’s full of blood –“

The reader, on the other hand, can read, and Adams provides us with the sign’s text:

THIS IDEALLY SITUATED ESTATE, COMPRISING SIX ACRES OF EXCELLENT BUILDING LAND, IS TO BE DEVELOPED WITH HIGH CLASS MODERN RESIDENCES BY SUTCH AND MARTIN, LIMITED, OF NEWBURY, BERKS.

From the opening pages, Adams’s approach to his rabbits is clear: while they talk and think, in the small things the rabbits of Watership Down will rarely act in unrabbitlike ways. They are small creatures in constant fear of the fox or the owl or the shot from a farmer’s gun. Grief over a companion’s death is to be expected but not lingered over, lest more death follow. They survive largely through speed and cleverness, not strength and aggression. On the other hand, they have a complex society with its own titles and terminology. Later chapters introduce tales of the great rabbit hero, El-ahrairah (Prince with a Thousand Enemies). Also, Adams’s rabbits are brushed with the fantastic. Fiver, based on Cassandra, is given to visions and premonitions that prove time and again to be true, if often unheeded.

When the Head Rabbit of Sandleford dismisses Fiver’s warning, Hazel gathers a small body of companions and they flee the warren. Among the rabbits are prophetic Fiver, Bigwig and Silver of the Owsla, clever Blackberry, and a few others. Over time, while all come to recognize Hazel as head rabbit, they succeed based on a more collective model, with each rabbit utilizing his strengths for the whole band. Together they face crossing a river, eluding a badger, and assorted other dangers.

The first part of their journey ends with the discovery of a peaceful warren led more or less by a somewhat dreamy rabbit named Cowslip. Without revealing the mysteries of Cowslip’s warren, it is one of the most haunting and disturbing parts of Watership Down. The refugees are confronted with rabbits who have abandoned the traditions of rabbithood, making them alien and strange and, in their own way, dangerous.

When Hazel’s band discovers Watership Down, a hill that offers them a truly safe place to build a home, they realize that without any does among them they are doomed to extinction. The quest to find some to join them on the down leads them into their greatest danger. While Hazel emulates El-ahrairah and frees several does from a hutch on a farm, a delegation is sent to a great warren they’ve learned is nearby.

The warren, Efrafa, is a totalitarian state run by the brutal General Woundwort and supported by an equally brutal council and Owsla. In the name of security, every Efrafan rabbit’s life is run to a schedule and overseen by Owsla officers. Overcrowding is severe and anyone attempting to leave is punished or even killed (non-fictional rabbits killing each other, particularly under stressful circumstances, isn’t uncommon). The ambassadors barely escape Efrafa with their lives.

General Woundwort is one of the great literary villains. Bigger and stronger than any other rabbit, driven by terrible events in his youth, he disdains the natural caution of rabbits and molds himself into a fighter able to drive off predators. Motivated by a need for domination as much as a real desire to establish a secure place for his subjects, he creates a strong, imperialist state Stalin would have admired. Like Cowslip’s warren, Woundwort’s Efrafa represents another society that has become warped through its rejection of history and customs in favor of security.

Though un-rabbitlike and savage, Woundwort is more than a simple one-dimensional villain. Even his enemies recognize his bravery. Even dogs don’t scare him. His downfall ultimately comes from his unwillingness to give up all that he had fought for, no matter what better future might be attainable. When Hazel comes to him with a sensible peace proposal, Woundwort rejects it.

“Very well,” said Woundwort. “These are the terms. You will give back all the does who ran from Efrafa and you will hand over the deserters Thlayli and Blackavar to my Owsla.”

“No, we can’t agree to that. I’ve come to suggest something altogether different and better for us both. A rabbit has two ears; a rabbit has two eyes, two nostrils. Our two warrens ought to be like that. They ought to be together–not fighting. We ought to make other warrens between us–start one between here and Efrafa, with rabbits from both sides. You wouldn’t lose by that, you’d gain. We both would. A lot of your rabbits are unhappy now and it’s all you can do to control them, but with this plan you’d soon see a difference. Rabbits have enough enemies as it is. They ought not to make more among themselves. A mating between free, independent warrens–what do you say?”

At that moment, in the sunset on Watership Down, there was offered to General Woundwort the opportunity to show whether he was really the leader of vision and genius which he believed himself to be, or whether he was no more than a tyrant with the courage and cunning of a pirate. For one beat of his pulse the lame rabbit’s idea shone clearly before him. He grasped it and realized what it meant. The next, he had pushed it away from him. The sun dipped into the cloud bank and now he could see clearly the track along the ridge, leading to the beech hanger and the bloodshed for which he had prepared with so much energy and care.

Both alternative societies — Cowslip’s and Woundwort’s — have turned on the things that have let rabbits survive and flourish in the face of their enemies and the natural dangers of the world. Both have perverted the souls of those in power. From one, Hazel and the others face temptation, and from the other, coercion. A major ingredient of the novel’s great appeal is the struggle for rabbitness against the forces that threaten it, which could easily be interpreted as the twin dangers humanity faces from intoxicating consumerism and the all-enveloping protection offered by statism.

Watership Down is also a great story of action, adventure, and, above all else, heroism. From the nighttime escape from Sandleford to the underground battles in tunnels under Watership Down, the novel teems with fast-paced and exciting moments. These scenes are crackling with energy and tension. If you somehow doubt rabbits’ adventures can be thrilling, you’re wrong.

Thlayli!” cried Thethuthinnang suddenly, from behind him. “The General! The General! Oh, what shall we do?”

Bigwig looked back. It was indeed a sight to strike terror into the bravest heart. Woundwort had come through the arch ahead of his followers and was running toward them by himself, snarling with fury. Behind him came the patrol. In one quick glance Bigwig recognized Chervil, Avens and Groundsel. With them were several more, including a heavy, savage-looking rabbit whom he guessed to be Vervain, the head of the Council police. It crossed his mind that if he were to run, immediately and alone, they would probably let him go as he had come, and feel glad to be so easily rid of him. Certainly the alternative was to be killed. At this moment Blackavar spoke.

“Never mind, sir,” he said. “You did your very best and it nearly came off. We may even be able to kill one or two of them before it’s finished. Some of these does can fight well when they’re put to it.”

If there’s a main character in the book, it’s Hazel. He finds the path to leadership fraught with physical as well as social peril as he follows Fiver’s visions straight into the unknown. His own uncertainty about their future is as much an obstacle to the group’s success as are any of the physical threats they face. He must learn how to draw on the individual talents of each other rabbit for their greater good, and create a community that’s more adaptive and clever overall. Ultimately Hazel, like El-ahrairah and unlike Woundwort of Cowslip, becomes a leader willing to lay down his own life to preserve his society and its members.

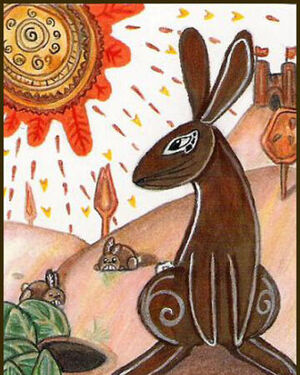

The stories of El-ahrairah help the reader understand rabbit society. Told at times to pass an hour or teach a lesson, they also describe the exemplary rabbit in all his faults and virtues. His arrogance and unwillingness to limit the growth of his people led the Creator, Lord Frith, to simultaneously curse rabbits with carnivorous enemies and bless them with cunning and speed. Hazel and the rabbits of Watership Down are spurred to astonishing acts of derring-do by stories of El-ahrairah’s cunning. He is able to get his enemy to deliver up his own lettuces to the rabbits, to outwit a jury of stoats, foxes, and dogs, and even to journey into the pits of Death himself, the Black Rabbit of Inlé. Adams’s text intimates that these tales underly many of our own tales — Brer Rabbit, for example, being but an avatar of El-ahrairah — and they are so profoundly mythic in their telling you can almost believe it.

Finally, Watership Down overflows with descriptions of all the living things that fill and cover a few square miles of Hampshire. All sorts of bird cries echo over the downs, badgers trundle dangerously along, while mice scamper about only to cower, even in the face of rabbits. Flowers, plants, and trees of a seemingly untold number of varieties blanket the landscape. If Watership Down wasn’t a real place, Adams would make you believe it was.

It was evening of the following day. The north-facing escarpment of Watership Down, in shadow since early morning, now caught the western sun for an hour before twilight. Three hundred feet the down rose vertically in a stretch of no more than six hundred — a precipitous wall, from the thin belt of trees at the foot to the ridge where the steep flattened out. The light, full and smooth, lay like a gold rind over the turf, the furze and yew bushes, the few wind-stunted thorn trees. From the ridge, the light seemed to cover all the slope below, drowsy and still. But down in the grass itself, between the bushes, in that thick forest trodden by the beetle, the spider and the hunting shrew, the moving light was like a wind that danced among them to set them scurrying and weaving. The red rays flickered in and out of the grass stems, flashing minutely on membranous wings, casting long shadows behind the thinnest of filamentary legs, breaking each patch of bare soil into a myriad individual grains. The insects buzzed, whined, hummed, stridulated and droned as the air grew warmer in the sunset. Louder yet calmer than they, among the trees, sounded the yellowhammer, the linnet and greenfinch. The larks went up, twittering in the scented air above the down. From the summit, the apparent immobility of the vast blue distance was broken, here and there, by wisps of smoke and tiny, momentary flashes of glass. Far below lay the fields green with wheat, the flat pastures grazed by horses, the darker greens of the woods. They, too, like the hillside jungle, were tumultuous with evening, but from the remote height turned to stillness, their fierceness tempered by the air that lay between.

In his essay “Epic Pooh,” Michael Moorcock condemns Adams for pushing “thoroughly corrupted romanticism — sentimentalized pleas for moderation of aspiration” painted with “middle-class Christian undertones.” Based on other things I’ve read by Moorcock, I suspect it’s the latter element that most irritated him. Aside from the anthropomorphization inherent in a novel of talking rabbits, there is little romanticism about animals in nature here; it is very red in tooth and claw, with constant terror and sudden death a rabbit’s lot in life. First, who’s to really say securing a safe, comfortable home in the face of predators, four-legged and two-, is a moderate aspiration? For the rabbits of Watership Down, it is a terribly difficult and dangerous goal to chase, and yet they do. To hold on to it they must put themselves at even greater risk. Finally, as to the middle-class Christian virtues, perhaps he meant self-sacrifice, but I’m not sure. If so, a story could do far worse than to focus on such a thing. Adams said once that he couldn’t imagine writing about characters who didn’t know right from wrong. Call me simplistic, but I’m all right with that.

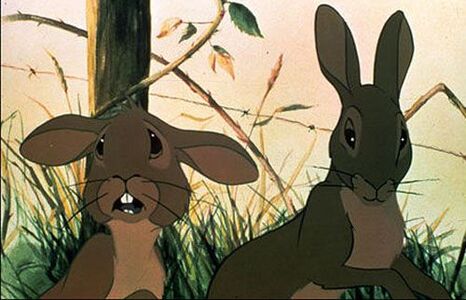

For a bit of proof that the novel is no milksoppy thing, I direct the interested reader to the animated Watership Down (1978), directed by Martin Rosen and John Hubley. It is a beautiful one-hundred-and-two-minute distillation of the novel and features fine animation, especially the Aboriginal-inspired artwork for the stories of El-ahrairah. It is also quite violent, with a fair amount of blood splashed across the screen. In a fortieth anniversary retrospective in The Independent, Ed Power described it as having “terrified an entire generation.” The cast includes John Hurt as Hazel, Richard Briers as Fiver, and Harry Andrews as General Woundwort, which I think should be sufficient for anyone to want to see the movie. Needless to say, though I will, I think it’s a very good movie. I haven’t seen either the 1999 television series or the 2018 one, but I’ve heard nothing particularly enticing about either one.

When I first read Watership Down, I was taken in by the adventure aspects of the main story and colorful ones of the rabbit myths. Revisiting it some forty years later those two things still hold, but I find myself completely pulled in by the non-allegorical allegorical facets, too. The heroism stands in contrast to the suicidal complacency of Cowslip and the dictatorial General Woundwort, and in these darkening times stands out as a bit of light against them. The theme of self-sacrifice, repeated several times in the novel, has a poignancy that meant much less to me when I was younger. It’s always a refreshing surprise to discover a book I remembered fondly has not only held up but is even better than how I remembered it. Now, I’m determined to finally read Tales from Watership Down (1996), a collection of stories set after the events of the original novel as well as more tales of El-ahrairah.

*“I first began reading his great work at the age of 30, in a state of great confusion,” recalled Mr. Adams. “I read ‘The Hero With a Thousand Faces,’ and it really changed my whole life. If it hadn’t been for Joseph Campbell, I would never have written ‘Watership Down.’ NY Times, 3/1/85

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

You’ve inspired me to reread it.

Cool, that’s what I’m striving to do

My favorite novel. I have numerous copies, including the illustrated edition, which is sumptuous.

It’s interesting that with the band of heroes Adams is explicit about everyone’s gift: Bigwig is strong, Fiver is a seer, Dandelion is the fastest even in a species known for speed (plus a good storyteller), Strawberry is attractive and well-spoken, Blackberry is the genius of the bunch, Captain Holly knows his woodcraft . . . Only Hazel’s quality isn’t expressly noted, but considering rabbits and their lives, it’s the rarest and most unique of all. Hazel is brave.

I really need to get that illustrated copy, it looks beautiful

I adore this book, and I think Moorcock’s own peculiar prejudices and obsessions hinder his ability to appreciate Watership Down as they do his ability to appreciate Tolkien.

Adams’ book did inspire a great Moorcock quote though, one which I think of often (this is from memory, so the wording may be a little off): “English science fiction and fantasy is written by rabbits, about rabbits, and for rabbits; American science fiction and fantasy is written by robots, about robots, and for robots.”

That is a funny quote, though I think it’s silly.

I think it’s pretty clear what Moorcock meant by it, and I think there’s more than a bit of truth in it.

Re-reading it in my forties (reading it aloud to my wife, who utterly adored it) was catching resonances with “The Aeneid.” Happily, Adams was too canny to follow Virgil’s plot beat by beat.

That’s very sweet. I’ve been planning to finally read The Aeneid this year.

We were having a conversation on some other blog about the relative merits of a particular book and the film inspired by it. I’ve always believed in the primacy of the written word, but – on reflection – realised I often found a book anticlimactic if I’d seen the film first; so I guess story-telling is all? I only mention this because ‘Watership Down’ was one example that got cited a lot (I’ve never read the book or seen the film): those who’d seen the film first loved it every bit as much as the book, if not more so.

Moorcock is being a bit glib, but yeah, I think his point is pretty clear. Bilbo, Frodo, Edmund and Titus Groan are not heroes in the traditional sense of the word. Unlike Moorcock, it’s something I actually like about English Fantasy. I guess you could also factor in a very English fondness for nature? And anthropomorphised animals? A character like Bilbo owes a lot to Mole in ‘The Wind in the Willows’, I reckon. Inversely, robots are strong and impregnable – not unlike many of Marvel’s superheroes.

And that’s disregarding an English tendency to fetishise the past compared to a US tendency to fetishise the future – rabbits being something I associate with Beatrix Potter and robots being something I associate with Isaac Asimov.