Vintage Treasures: Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home by James Tiptree, Jr.

|

|

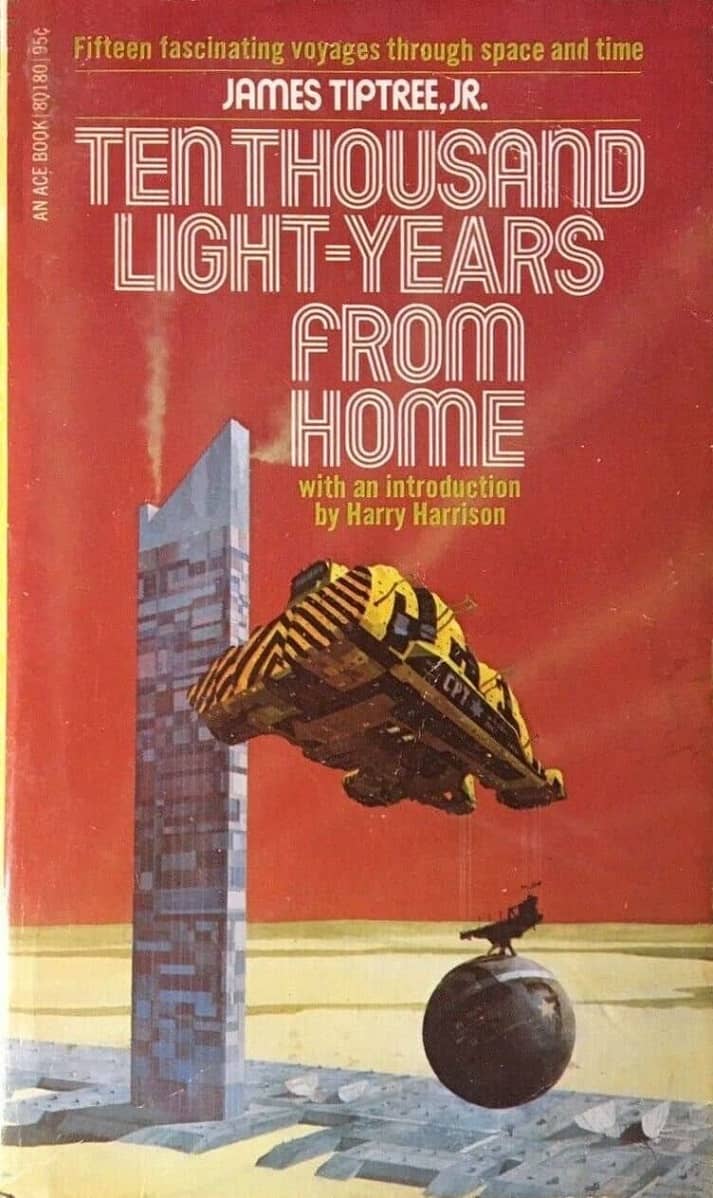

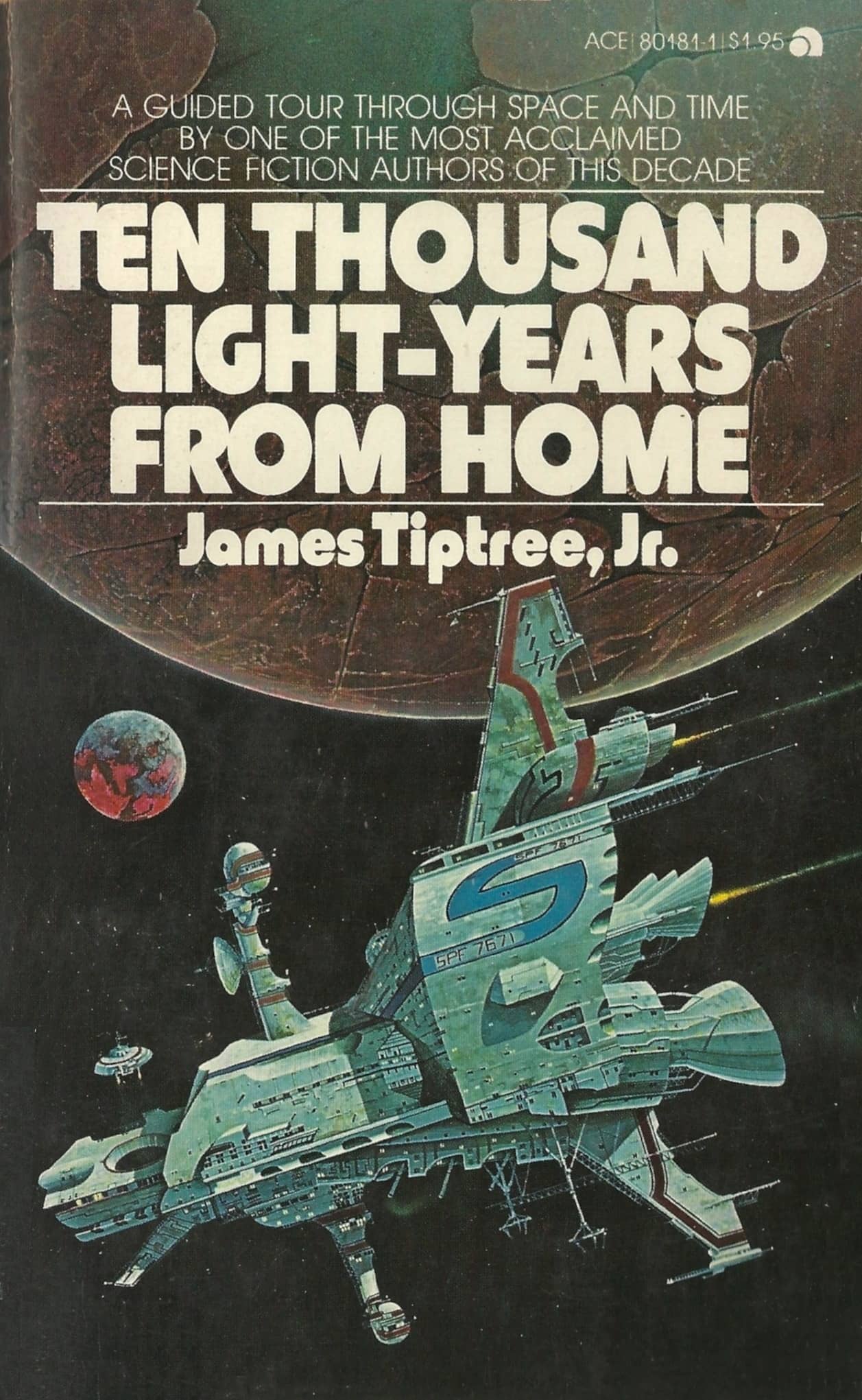

Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home (Ace Books, 1973). Cover by Chris Foss

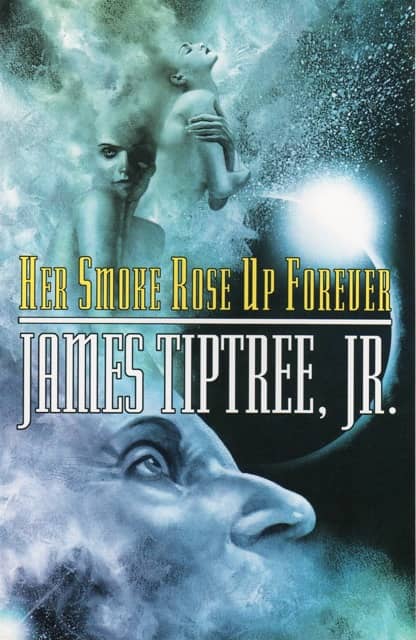

Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home was the debut collection from one of the most important science fiction writers of the 20th Century, James Tiptree, Jr (the well known pseudonym of Alice B. Sheldon). Tiptree published half a dozen additional collections during her lifetime, and several very important volumes gathering her best short fiction have been assembled since her death, most notably Her Smoke Rose Up Forever (Arkham House, 1990), one of the seminal SF books of the century.

But it probably won’t surprise any of you to learn that I still prefer the original paperbacks, flawed and poorly edited as they were. Thomas Parker called Ten Thousand Light Years from Home “the worst-proofread book I’ve ever read,” and let’s just say he’s not the only one to notice.

|

|

|

|

|

|

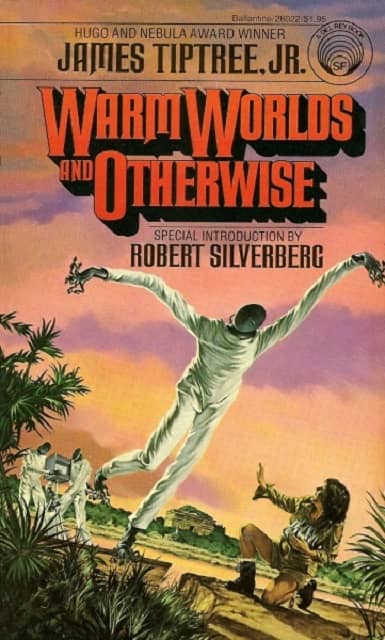

Some of Tiptree’s other collections: Warm Worlds and Otherwise (Del Rey, 1979, cover by Michael Herring),

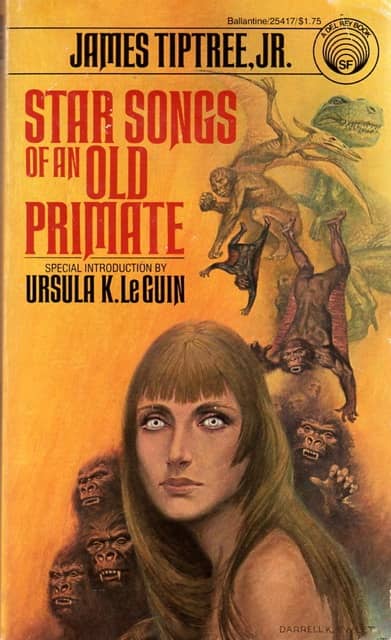

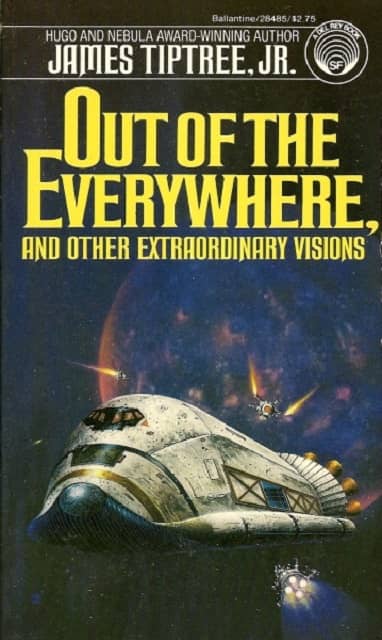

Star Songs of an Old Primate (Del Rey, 1978, Darrell K. Sweet), Out of the Everywhere and Other Extraordinary

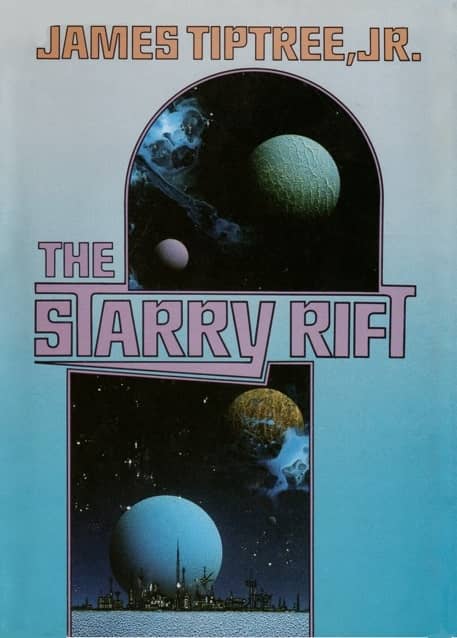

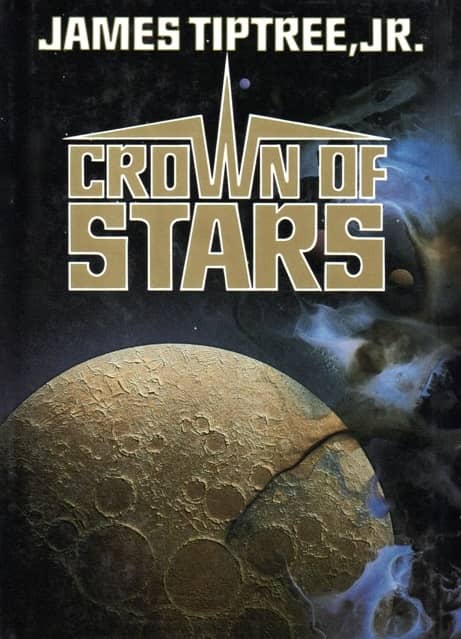

Visions (Del Rey, 1981, Rick Sternbach), The Starry Rift (Tor, 1986, Dave Archer), Crown of Stars

(Tor, 1988, Dave Archer), and Her Smoke Rose Up Forever (Tachyon Publications, 1990, John Picacio)

Tiptree’s fiction is so varied and unpredictable that I’m a little reluctant to try to classify it. One thing I will say is that it deeply rewards rereading — or it’s always rewarded me, anyway. One of my favorite Tiptree tales, “The Women Men Don’t See,” is narrated by a clear-eyed and observant government agent whose plane goes down on the coast of Quintana Roo in Mexico, where he and his fellow passengers encounter enigmatic aliens in a mangrove swamp.

Except, that’s not what it’s about at all. Read that way (which is precisely the way I did read it, in the pages of The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction), the ending makes no sense.

It’s only when you begin to realize that our confident and sure-voiced male narrator has absolutely no clue what’s going on — and his assumptions about his companions, especially the women, are wildly off-base — that the deeper story starts to come into focus.

|

|

Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home (1978 Ace reprint). Note the new cover text. Cover by Patrick Woodroffe

Alice Sheldon didn’t tend to comment deeply on her own stories. But she did conduct long-lasting correspondence with several fellow SF writers, and this is what she said privately about “The Women Men Don’t See,” as quoted in Wikipedia.

Tiptree’s own synopsis of the story concludes “Message is total misunderstanding of women’s motivations by narrator, who relates everything to self,” and who can only see women sexually: the women are practically invisible to him, except when he thinks of them as potential erotic interests…

Feminist narratives with clueless male point-of-view characters aren’t uncommon, of course, but you didn’t usually find them in SF magazines in the early 70s.

And to stealthily slip this kind of fiction into the pages of F&SF, dressed up as male-centered adventure SF (written by a man) and with a self-assured narrator who behaved and sounded exactly like the main characters of virtually all of the most popular science fiction at the time, meant that it was consumed unguarded by readers both male and female — and it promptly wrenched their heads around.

“The Women Men Don’t See” was — no surprise — one of the most controversial and debated stories of 1973 (and 1974, and well into the 80s) and remains one of the most discussed SF stories of the last century. It was selected by Terry Carr for his Best Science Fiction of the Year #3, and collected in Warm Worlds and Otherwise, and it has been reprinted dozens of times since.

|

|

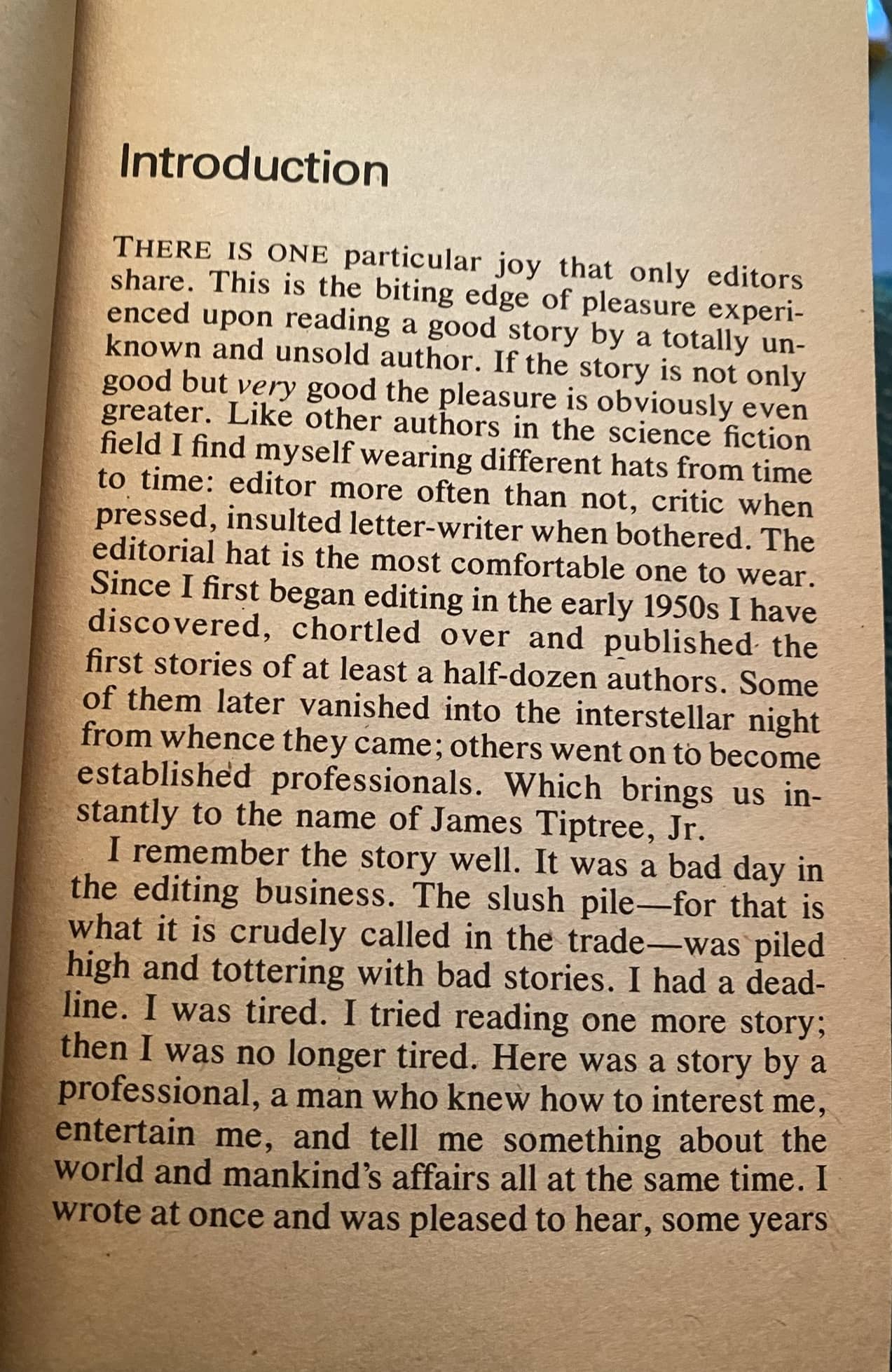

Harry Harrison’s introduction to Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home

One of the reasons I put up with the low-budget editing of Ten Thousand Light-Years From Home is I enjoy the introduction by Harry Harrison, who takes delight (justifiably) in being the editor who first discovered Tiptree in 1967. Her identity remained a secret until obsessive fans tracked her down in late 1977, so Harrison was unaware of her gender when he wrote these words.

I remember the story well. It was a bad day in the editing business. The slush pile — for that is what it is crudely called in the trade — was piled high and tottering with bad stories. I had a deadline. I was tired. I tried reading one more story; then I was no longer tired. Here was a story by a professional, a man who knew how to interest me, entertain me, and tell me something about the world and mankind’s affairs all at the same time. I wrote at once and was pleased to hear, some years later, that the word from me arrived just one day before a check from John W. Campbell. Now that is the way to start a career in science fiction.

Tiptree is a professional because he cares about his work and keeps on caring. He reworks it himself until he has it right, then reworks it some more aiming at an unobtainable perfection. He is fun to work with because he actually thanks an editor for pointing out something that needs brushing up. But most of all he is a professional because he writes the kind of fiction that is worth reading and is a pleasure to read at the same time.

There is a temptation in an introduction of this kind to be very biographical and spend a good deal of time on the author’s lovely dark hair or firm waistline despite his advancing years. I shall resist this because the fiction, the stories before you, are what really counts.

The story Harry mentions in that first paragraph is almost certainly “Fault,” which appeared in the August 1968 issue of Fantastic, edited by Harrison. (Campbell bought “Birth of a Salesman,” which beat “Fault” into print by five months, appearing the March 1968 issue of Analog, making it her first published SF story).

It must have been ironic to Tiptree that she couldn’t escape having a male editor comment on her “lovely dark hair [and] firm waistline,” even by disguising herself as a man.

Ten Thousand Light Years from Home includes the famous Star Trek story “Beam Us Home,” and two Hugo nominees (“Painwise” and “And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side,” which also garnered a Nebula nod). Here’s the complete table of contents.

Introduction by Harry Harrison

“And I Awoke and Found Me Here on the Cold Hill’s Side” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, March 1972) — Hugo and Nebula nominee

“The Snows Are Melted, the Snows Are Gone” (Venture Science Fiction Magazine, November 1969)

“The Peacefulness of Vivyan” (Amazing Science Fiction, July 1971)

“Mamma Come Home” (If, June 1968)

“Help” (If, October 1968)

“Painwise” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, February 1972) — Hugo nominee

“Faithful to Thee, Terra, in Our Fashion” (Galaxy Magazine, January 1969)

“The Man Doors Said Hello To” (Worlds of Fantasy, Winter 1970)

“The Man Who Walked Home” (Amazing Science Fiction, May 1972)

“Forever to a Hudson Bay Blanket” (Fantastic, August 1972)

“I’ll Be Waiting for You When the Swimming Pool Is Empty” (Protostars, 1971)

“I’m Too Big but I Love to Play” (Amazing Science Fiction, March 1970)

“Birth of a Salesman” (Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact, March 1968)

“Mother in the Sky with Diamonds” (Galaxy Magazine, March 1971)

“Beam Us Home” (Galaxy Magazine, April 1969)

Ten Thousand Light Years from Home was published by Ace Books in July, 1973. It is 319 pages, priced at 95 cents. The cover is by Chris Foss. It has been reprinted over a dozen times, and an e-book version was published by Gateway/Orion in 2015.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Badly proofread or not (I ditched my Ace paperback and got a hardcover copy of the British Eyre Methuen edition) it’s an essential book for any Sheldon/Tiptree reader, especially since a lot of the stories are her early ones, written before she found her real voice and for that reason not often reprinted. Even so, It does have my single favorite Tiptree story, “The Man Who Walked Home,” a mind-blowing pure sf idea given a deeply human, tragic dimension.

I blinked, too, at the mention of “lovely dark hair or firm waistline”, which is so very typical of comments associated with women subjects instead of men subjects of interviews or profiles. I would not hazard a guess at Mr. Harrison’s intentions, only to comment that, yes, the irony is delicious.

First time I read it, I wondered if he was trying to signal that he had some clue to her identity? Doubtful in 1973, but it made me wonder.

The Silverberg intro to Warm Worlds and Otherwise is the real firecracker. There had started to be “maybe he’s a she” talk by that time, I think, and Silverberg just doubled down, talking about Tiptree’s unmistakably masculine tone or something like that. Whoops.

Tiptree is another one of those authors that I haven’t read in about 30 years and should probably change that Real Soon Now. I do have both of her Arkham House collections, although they’re currently in a box somewhere …

And I love that Chris Foss cover on the original Ten Thousand Light Years from Home.

I’m the proud owner of every edition pictured above — the first (and sure to be only) time that’s happened for a Vintage Treasures post.

Tiptree was my very first Favorite Writer when, in my later teen years, I’d begun to discover SF with thematic / artistic dimensions beyond pure space adventure. It was gratifying for me in the early 2000s or thereabouts when her reputation seemed to enjoy something of a renaissance. The biography by Julie Phillips is really good — recommended reading for anyone wishing to know about Tiptree / Sheldon’s amazing back story.

I have not read Phillips’ bio, but I really need to. It’s still in print, which is nice.