Co-op Adventuring in Dungeons & Dragons

When I started playing RPGs all the way back in the early 1980s, I did not have a group of players at my age to play games with (well, at least none that I ever found). Hence, I subjected my brother to Traveller and Star Frontiers — and eventually Marvel Super Heroes, Twilight: 2000, and others. RPGs had always presumed that the game would have a game master (GM) — sometimes called Dungeon Master, referee, storyteller, keeper, and others — and the players.

The GM is largely responsible for crafting the story, running all the non-player characters (NPCs), adjudicating the rules, and responding to player decisions by adjusting the story as necessary. Hence, I acted as the GM and my brother played the characters in the story. Typically, far more players are looking for GMs to run games than GMs hanging around without players. This is, of course, highly dependent on the games being run, location, and so on. With online gaming, it is usually more challenging to coordinate time zones.

That said, GMs may have trouble finding players to play anything but the giant of all RPGs, Dungeons & Dragons. However, D&D often serves as a gateway to other RPGs, and the incredible success of Cyberpunk Red and Aliens shows that as more players enter the hobby, a fair number are willing to expand beyond the D&D horizon.

I have always been what is known as a “forever GM.” I wear that title proudly. I love GMing. I prefer it to playing as a character. However, I have often wanted to try out games solo or game with my brother where we both play characters. How does one do that without a GM?

Solo play has been around since the earliest days of the hobby, but over the past few years and even more so with the pandemic, solo play has received a significant signal boost. Games like Ironsworn and Free League Publishing’s edition of Twilight: 2000 include solo play in the rules.

Many of the tools used for solo play can also be used for GM-less group play, also called co-op playing. The key tool needed is a GM emulator or oracle. Something that can essentially act as the GM to answer questions about the environment. RPGs are about talking and asking questions. A typical bit of dialogue is:

GM: “You enter the station’s airlock. The interior door is closed, but the red emergency lights are flashing. You can tell the ship has lost its gravity controls for the straps that normally hold emergency space suits are floating. What do you do?”

Player 1: “Is the control panel for the exterior door intact?”

GM: “Yes. The light is red.”

Player 1: “I’ll press the close button.”

GM: “Okay. The exterior door slides shut. The panel’s light shifts from red to yellow.”

Player 2: “Where is the control for pressurizing the airlock.”

GM: “Next to the interior door’s control panel. As you look at it, you see that it has scorch marks and it looks severely damaged.”

And so on. The players make some dice rolls and combat may (or may not) get more tactically oriented. The thing is, it is a constant interaction between the players and the GM fleshing out the environment. This is part of what keeps an RPG game something different than a few people sitting together and creating a story together (it’s not the only thing, but RPGs are an improvisational, collaborative, story telling activity). Without the distinction between a GM and the players, many of the questions could simply be answered by the players. This is where GM emulators come in.

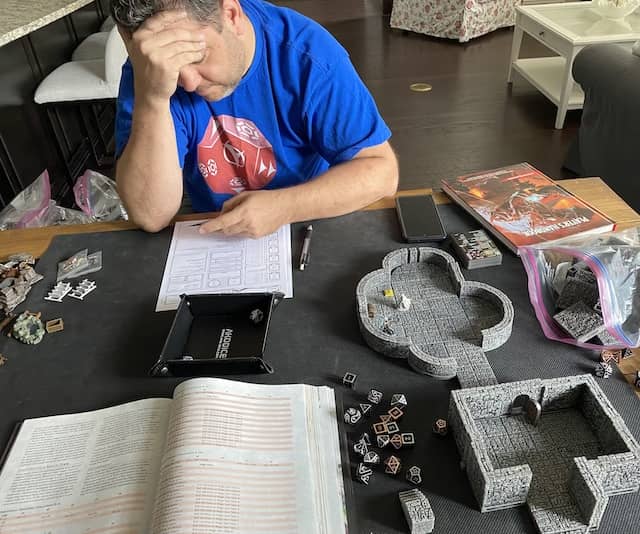

My brother recently visited me (he lives a few hours away), so we engaged in a marathon session of games over a long weekend. Instead of playing our typical RPG of me GMing and he playing multiple players, we wanted to give a co-op game a try. One where we both played a character. I had also recently discovered Warlock tiles by WizKids, and I wanted to be able to use those, but if I built out a setting or a dungeon or a temple, then I would, in some ways, be determining parts of the story. So we decided to try to emulate even that bit as much as possible — that is, we determined to use random generators for even the scene’s particular environment.

We decided to use D&D’s 5th edition rules and created twin half-elves. I played a storm sorcerer and he played a fighter. We both chose the urban bounty hunter background. This was part of a backstory we agreed to together. We then prepared our tools for running a GM-less game:

Mythic cards by Word Mill

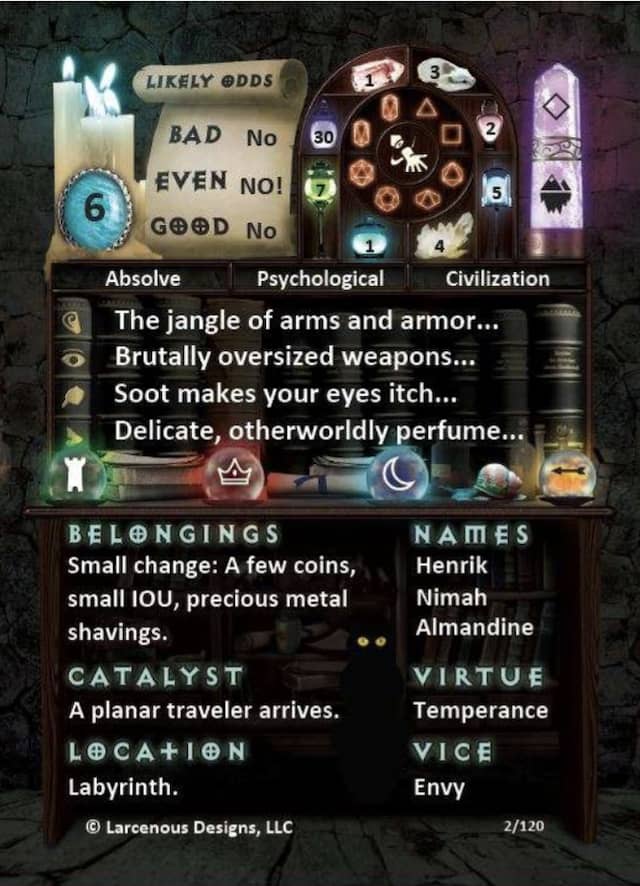

GameMaster’s Apprentice (Fantasy deck) by Larcenous Designs

Dungeon Master’s Guide by Wizards of the Coast

Critical Hit deck by Nord Games

Critical Fail deck by Nord Games

Treacherous Traps – Random Trap Generator deck by Nord Games

We also determined beforehand that we would keep it pretty simple and viewed this essentially as a singular game (versus a campaign). The twins had a mark to acquire and that mark would require us navigating a dungeon. We picked two potential marks — I pulled out an orc war chief mini and necromancer mini and gave them to my wife. We also determined the mark would be in a tower. My wife placed the mini she chose without us knowing in the tower.

We started by determining some of the details of the person who hired us and a bit about the mark (though we artificially kept the knowledge of an orc or necromancer hidden). Then we played.

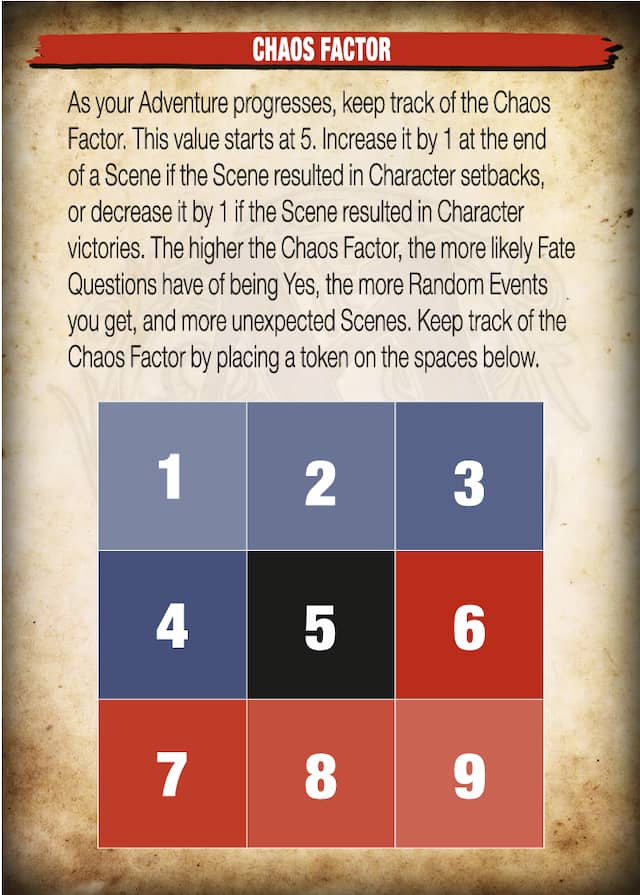

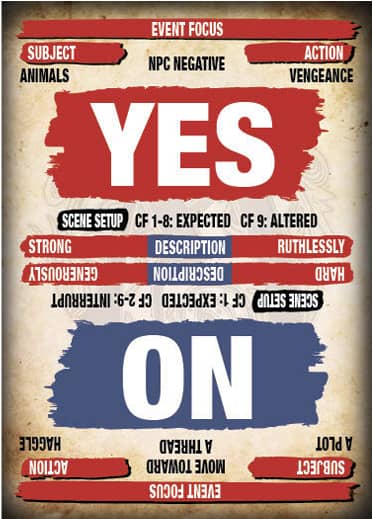

The Mythic cards at their core answer Yes or No questions. “Is an undead trapped in that glass container?” You determine a starting Chaos factor — which represents how, well, chaotic the current scene is based on the results of the last scene. We started the game at the neutral 5 setting. Then in the first scene, my brother’s character attempted to persuade a few ruffians who did not like elves — even half-elves — with drinks. They did not take kindly to the offer and a brief fight took place. We agreed to up the Chaos factor to 6 because the entire situation seemed to warrant that. Understanding how this affects the game requires digging in a bit deeper to how Mythic works.

Every card has two halves — and you work with the half that is upwards when you deal it. You then determine how likely the answer to your question is a Yes or No. This is, of course, subjective, but with considered thought, you can usually determine a reasonable answer. “Is this door locked by a coiled demon inside the chains?” Probably not. Locked by a complex mechanism, more likely a Yes. The likelihood of the answer is then combined with the Chaos factor, which determines both the number of cards drawn and the results you need for the answer.

For example, if you gave it even odds (50/50) that the answer would be Yes and the Chaos factor is 5, then you draw a single card. If it shows Yes, then that’s that your answer. However, if the Chaos factor is 8 but you keep the same odds (50/50), then you draw a extra two cards (so three total), and if any card shows Yes, that is your answer.

The Mythic cards offer a wealth of other tidbits, including Exceptional Yes’s and No’s, scene interrupts, links back to previous NPCs, scene focus, and action and description mechanisms. Several of these we did not run in our play through, but one can see the power in them.

Using this method does take some getting used to — or practice. Just like the rules of an RPG need some playing with, so does working with the cards and the variety of results. And the results must be interpreted by you. In the case of the game my brother and I played, we worked together on deciding what a Yes meant. This is particularly the case with more abstract questions.

As we worked our way through the dungeon, we rolled the dungeon layout using D&D’s Dungeon Master’s Guide tables for random dungeon generation. Passage by passage and corridor by corridor. We then rolled for what the chamber contents were (a table in the Dungeon Master’s Guide). We often used the GameMaster’s Apprentice deck to provide flavor details, particularly about how the chamber or passage was: Did it smell? Were there weird sounds, etc. We’d pulled from the deck, examined the number of options, and chose the one that made the most sense.

Putting this all together: in one instance, we entered a 20 x 20 chamber in which we heard loud laughter. In that room, we rolled that it had a trick and that the trick was centered on a glass sculpture in which a creature was trapped. We then proceeded to use the Mythic deck to ask questions about that glass sculpture:

“Is the creature in it an undead monster?”

Result was no.

“Is the creature in it an sentient being?”

Result was yes.

“Is the sentient being a vampire?”

Result was no.

“Is the sentient being a dwarf?”

Result was no.

Eventually, we landed on the fact that the sentient being was a Druid trapped in hyena shape.

Based on that, we determined the loud laughter was coming from the glass sculpture and it was the hyena’s laugh. The Druid ended up assisting us as we battled a Kuo-toa archpriest that nearly killed my character. The Druid then fled the dungeon, but the Kuo-toa was guarding a treasure with a carpet of flying that was particularly helpful in escaping a nest of giant spiders as we were being pursued by a bugbear that had killed another group of bounty hunters trying to get the same mark as we were.

All of the above was generated using Mythic, the GameMaster’s Apprentice, the Dungeon Master’s Guide, and our interpretation of the results. Once we got into the groove of the game, it felt very much like a D&D session, though it was a bit more tactical/combat oriented given both the fact it was a dungeon crawl and many of the opponents were disinclined to parley.

Traps were a bit tougher simply because triggering them required knowing that a trap was in place and what the trigger was. We worked around it by using Mythic to determine if a trap was present and the difficulty of finding it. We then determined the likelihood our characters would investigate for traps based on location, situation, and previous encounters. If a trap was present, we used Nord Games Treacherous Traps – Random Trap Generator deck. We pulled out the Trigger card to determine what would spring the trap. We used Mythic and common sense to help drive the approach and difficulty. If we triggered the trap, then we pulled the Effect card to determine what was unleashed. In one instance, we pulled that a bunch of skeletons rose from piles of rubble, which we randomly determined the number of by rolling a four-sided die.

Overall, the combination of the Mythic yes/no format, the random tables for generating the dungeons, and the Random Trap Generator deck all provided a keen sense of the unknown. We did not have an idea of what would come next. Sometimes passages would wind and wind before opening to a chamber. The occasional stairs took us up and down. Yellow mold and monsters provided obstacles. While not perfect — an emulator cannot, of course, replace a real live human being as the GM — the game still had the feel of an RPG that we were negotiating our way through. I do think co-op works best with a group that is already familiar with each other and is willing to engage in the work to interpret the results of what the emulators and decks provide.

We did use the Critical Fail and Critical Hit decks to provide those results instead of making them up ourselves. That seemed “fair” within the context. Overall, it was a blast. We eventually caught our quarry, an orc war chief named Fadi. Well… the contract said dead or alive. Oh, and the Mythic cards we drew for whether Fadi was wanted dead or alive came back with an exceptional yes to our question: “Do you prefer the mark to be brought back dead?” The oracle spoke….

If you want to obtain any of the items above, you can find them at:

Mythic Game Emulator deck

The GameMaster’s Apprentice: Fantasy Deck

Critical Hit deck

Critical Fail deck

Treacherous Traps – Random Trap Generator deck

Patrick Kanouse encountered Traveller and Star Frontiers in the early 1980s, which he then subjected his brother to many games of. Outside of RPGs, he is a fiction writer, avid tabletop roleplaying game master, and new convert to war gaming. His last post for Black Gate was Reckoning: Twilight: 2000’s American Campaign. You can follow him and his brother at Two Brothers Gaming as they play any number of RPGs. Twitter: @twobrothersgam8. Facebook: Two Brothers Gaming.

A very nice set of tools you have assembled, Mr. Kanouse, for some co-op referee-free roleplaying. I am a fan of the Fortune Deck from Everway (and just received my copy of the new Deluxe version from the latest edition) as a way to allow players and ref to get a randomized answer that contains all kinds of ambiguity (like pulling The Eagle – “The mind prevails”) just waiting to be interpreted in the context of the scenario.

I have played some of the newer indie games that operate without a referee, like Fiasco, and I particularly like the Powered by the Apocalypse style that removes much of the “privilege” of the referee and returns it to the players. But even with PbtA, I find that I still like to hold onto a pair of dice even if the game does not permit me to roll them in any significant moment.

Eugene! Thanks for reading and commenting! I’m going to have to check out Everway. The newest Twilight: 2000 uses a standard deck of cards. Yes/No answers rely on color. The value of the card determines how strongly or negatively the yes or no is or how hazardous or non hazardous the situation is.

I do like my dice, and I still feel like I get to roll them in many of these solo games. 🙂