Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds #3: Tricks of the Trade and Reflections

I’m doing a deep dive into Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds (first article), and I’ve finally gotten to his last chapter in which he gives advice to writers:

When a writer first begins evolving in his imagination and his notebooks, the raw materials that he intends to shape into an imaginary world, he should think through the problem through to its logical ramifications.

Because…

…despite the convictions of occultists and the religiosi of the several faiths, in the actual world magic simply does not work… and an invented world, therefore, that includes the super natural element must be–has to be–very different from his own. Any writer…. should think through all its implications.

If you’ve just tuned in, Lin Carter was a Fantasy author and editor who flourished roughly from the 50s to the 70s. He was a far better editor than author, however his stories are reliable comfort reads, and compensate for lack of depth with fast pacing and unconstrained imagination. No surprise, then, that his thoughts on Fantasy worlds are worth reading. He gives them in X entertaining secions.

1. Magic

Magic (says Carter) has to have limits. It’s no good if the magician can snap their fingers to get out of a dramatic situation. The proven is to create systems with limits. Superman has his Kryptonite, Sauron has his One Ring. Coming closer to his favourite subgenre, Jack Vance’s mages of Dying Earth can learn but four spells at a time, and can only carry so many magic items:

Either the magician will encounter perils for which he is unprepared, or he will exhaust his magical armament… Vance has admirably thought through the implication of the invulnerable magician problem.

And, though he does not spell it out, he implies that the limitations themselves can big up the magic: these spells are so very powerful you can only remember four.

2. The Problem of Realism

If magic does practical things, then…

physical sciences… are not only superfluous, but also somehow out of place.

Carter does not believe you can mix gunpowder, and science, and magic. (I think we know he’s wrong. First, the classic era of visible post-Roman western occultism was the Renaissance. Dr John Dee, whose Black Mirror you can see in the British Museum, summoned angels, did alchemy, and worked as a court astrologer for Elizabeth I of England, who had an awful lot of arquebuses and cannon at her disposal. Second, there are some very successful books that mix the two — if you can think of some, please share in the comments.)

Citing examples gleaned by CS Lewis, Carter goes on to tell us that in a world of magic, the gritty telling detail grounds the reader:

The careful use of precise, vividly realised, on-the-spot descriptive detail can work miracles in bringing to life the on the page imaginary beings, fantastic scenes, supernatural events.

Thus we see Beowulf’s dragon “sniffling along the stone” and Fairy bakers in another tale “rubbing the paste off their fingers,” and in more modern fiction Dunsany having a dragon play cat-and-mouse with a captive bear, and Brackett’s exotic Martian women having bells in their hair.

A final option — but not mandatory — is what Carter calls “the John W Campbell School of Realistic World-Making” where the author works out some of the underlying science. This gives us such gems as:

Look, if the creature breathed fire, then it had to be even hotter inside. So I tossed half a gallon of water down its gullet. Caused a small boiler explosion.

3. The Problem of Business

By “business”, Carter says he means the theatrical term referring to “the extra touches actors put into their stage activities”. However, it’s clear that what he really means is “telling details pointing to setting and the character’s place in it”. Don’t just talk about any street, give the thing a name. And if you name a place, tell us its reputation, e.g. Lovecraft’s Sarkomand, famed for its huge winged lions of diorite. Have the characters inhabit a world of ritual and reputation, and association and implication.

4. The Problem of Flora and Fauna

In closing, Carter runs headlong into the war mammoth in the room, and somehow manages to get his head stuck in its… um… mouth. Definitely mouth.

When a fantasy world is clearly specified as a non-terrestrial planet… it should not include familiar earthly birds and beasts.

Sure, says Carter (I paraphrase), you can argue that if humans are there, then so too will be horses and dogs and pine-trees. However, he’s clearly drawn to “science fiction world-making” and thinks if you have to have human characters to relate to, perhaps they can be humanoid and lay eggs and have horns and stuff?

I mean… it can work? We love the world building of Edgar Rice Burroughs. However, it turns out reading for escapism isn’t the same as wanting to grok a whole load of made up plants and animals. Fantasy, especially Swords and Sorcery, deals in archetypes. To want to go down that rabbit hole, we need to really really care about the world, and perhaps there are only so many cultural slots for this kind of thing.

So it is that Carter ends his book with a flourish, albeit perhaps a wrong-headed one that is however consistent with his simulationist approach.

I’m glad I read this book.

Lin Carter is above all else good company. He’s looking back one generation to what is now our genre’s Heroic Age, a wild and woolly era of unbounded creativity separated from us by a gulf of a century — I am reminded of when, as a teenager, I bought a drink for an elderly jazz musician, who in turn told me about going out on the town with Fats Waller, and the perils of playing for Jelly Roll Morton.

Carter is also writing in what, looking back, was a great time to be a Fantasy author. The books were short and quick to write, fandom was growing but still a secret club, the field was expanding. Anything seemed possible — it’s nice to get a patchouli-scented whiff of the optimistic air of that era.

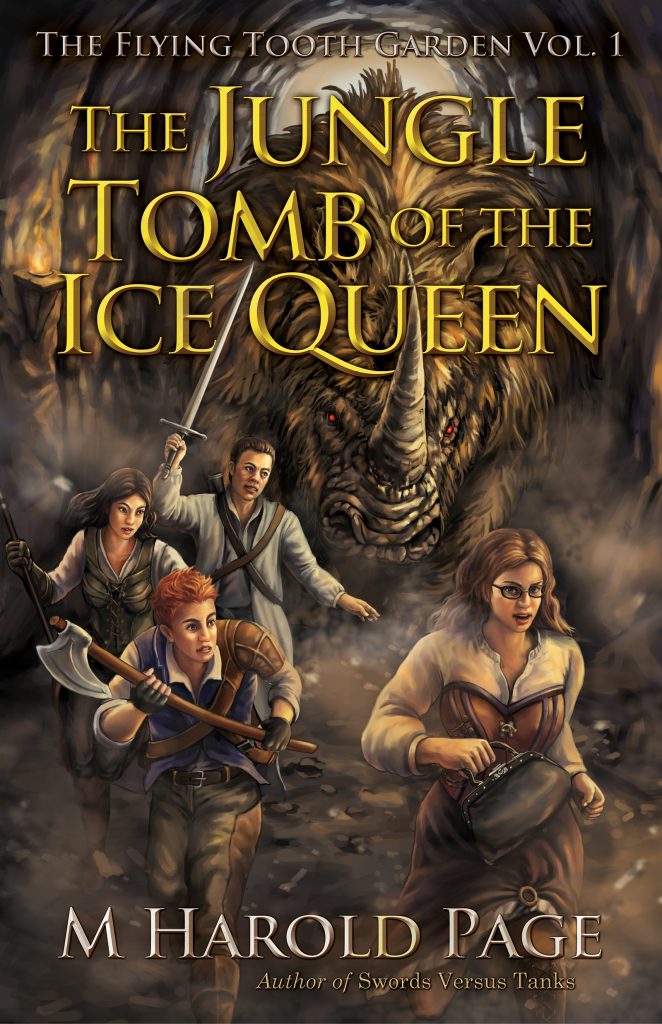

Did I take his advice while writing The Jungle Tomb of the Ice Queen? Yes… No… Sort of.

Cover, Level Up Publishing. (Yes, that is a zombie woolly rhinoceros on the cover.)

Carter’s specific advice on world-building is now industry standard. Did he establish the rules, or merely set down the emerging laws? I don’t know. (Tell me what you think in the comments.) Either way, if you are writing modern commercial Fantasy of any kind, then genre conventions mean that you’re probably already following Carter’s advice, even if it came to you by osmosis or reinvention.

So it is that my story has a setting formed in part by the magic that flourishes there — structures and strategy, even economy, all reflect the possibility of sorcery and supernatural creatures — but I would have done that anyway, because this is where my head lives. Imaginary Worlds served only as a handy reminder.

All that said, in setting out his advice, Lin Carter reveals the secret of what makes his books so enticing, despite their lack of thematic meat or deep characterisation (though these can also be literary features as well).

First, Carter is a simulationist. He builds what we could call Hard Fantasy worlds: they are each a thing in themselves, extrapolated from a handful of Fantasy premises. He doesn’t do the stock fantasy quasi-European map. You know the kind of thing: Here’s Westerland. North are the Horned Helmet People. East is Furry-Hat-Light-Horse-Land. Cross the Middle Sea and you get to Egyptarabia. Travel many, many leagues and you’ll reach Indoninjachinapan. Nope. Carter always takes you somewhere new. His settings are constrained by tech level and human nature, so deliver familiar types and hence tropes, but we’re not in Kansas anymore. Dreamlands, perhaps.

Second, he’s very keen to put our boots on the ground in that simulation. No, he doesn’t foreground gritty details the way Howard did, but he does use his tricks of the trade to give us a sense that the rest of the world exists not just beyond the horizon, but also in the past.

Finally, he uses sleight of hand to make the exotic setting somehow relatable. He talks explicitly about fine tuning the names of things. However, as we can tell from references in Imaginary Worlds, he also lifts historical processes and structures. He may not be writing actual history, but he usually delivers a history.

Some of that did go into The Jungle Tomb of the Ice Queen. I did create a setting that was its own thing, based on magic and reincarnation. There are some recognisable types, and the main character blatantly uses authentic German Longsword in all his fights. However, with the exception of one feudal region of my multiverse, I managed to not just replicate a quasi medieval setting… and it was liberating. Thankyou Lin Carter.

So, if you can get hold of it, read Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds for fun and inspiration, and a succinct inside take on world building and the literary tricks of the trade. If you are just starting out on fictioneering, this is still a good place to start.

Our previous articles on this book include:

Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds #1 History Of Fantasy

Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds #2 World Building And Naming

A Contagious Love of Fantasy: Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds by James McGlothlin

M Harold Page is the sword-swinging author of Swords Versus Tanks. Go take a look at his latest novel, The Flying Tooth Garden Volume 1: The Jungle Tomb of the Ice Queen (A Reincarnation LitRPG)!

Funnily enough, I was reading your last article earlier in the week! I then tried – unsuccessfully – to track down Lin Carter’s article about Tolkien on-line. No luck. Although I did discover he was exactly the same age as I am now when he died.

Re Vance. Who could ever forget ‘The Spell of Forlorn Encystment’ which results in the victim suddenly finding himself interred deep beneath the earth? I’m pretty sure I’ve mentioned this particular spell on Black Gate before….

‘The Problem of Flora and Fauna’ made me think of Lewis’s Perelandra series in which he tried to conjure up an entirely alien world with mixed results. OK, the books aren’t great, but I think he was taking more risks than he did with the Narnian books in terms of world-building. That said, maybe doing so exhausted him to such a degree that he decided from then on to draw on more traditional source material. Plus (like you say) if the world and its inhabitants are too alien, it’s difficult for the reader to identify with them. Maybe he came to the same conclusion?

Lewis’s Space Trilogy books “aren’t great”?! Aonghus, Aonghus, where did we fail you…

Hah! Are you a fan, TP? I read them a very long time ago.

I am, Aonghus, though I have to admit that I read those particular books a long time ago myself. My most recent Lewis read is Till We Have Faces, which is, I think, his greatest achievement in fiction.

‘Till We Have Faces’ is his best work, imo. Orual is such a great character.

I think Carter would have liked to think that he was establishing the rules of the genre, but I don’t think he did. His writings about fantasy and science fiction are fascinating and often illuminating, but at other times so confounding and frustrating that I find myself wanting to distrust him even when he’s spot on. He’s very much wrapped up in his own frame of reference, and it sometimes produces odd results.

I think that’s fair. It’s a bit like an old fencing compendium.

Great article, Martin! I thoroughly enjoyed it. While I’m not one of Carter’s biggest fans, this book sits on the shelf above my computer. It is my go-to book when writing a fantasy, because it has been a wonderfully helpful guide and mentor to me, to my writing, since 1973. Bravo!

Thanks! I think I myself shall be tracking down a copy of the book. His understanding of the genre far exceeded his capacity to write it well.

Carter was eccentric without a doubt, but when you disagree with him, you know you’re disagreeing with someone whose reading in fantasy is deeper and wider than yours will ever be. It doesn’t necessarily make him right, but I’m sure it made him a hard man to win an argument with.

I would love to have had a beer with him!

Glad to see some appreciation on Lin Carter. I found this book years ago and still have and love it. Myself I’m a big fan of Lin Carter and have found most of his books, from the fictions (including the Gondwane epic) to his non-fiction books about other books. This is one of my favorites.

IMO, Lin Carter was a good writer but a genius level editor. The latter diminished his reputation as a writer because he saved so many greats from obscurity -Lord Dunsany and Clark Ashton Smith most of all – but also IMO lots of things such as “Forgotten Foundations” by Hodgeson and others would have indeed been forgotten. However his own passion for that genre and his own works often being his own ‘Sword and planet’ or various other style of tales he was often seen as derivitive. Indeed they cancelled Thongor of Lemuria to start publishing Conan and he cheered it on of all things. Of course he also started “Brak the Barbarian” because John Jakes came by with his ‘own Conan story’ but the people who’d ignored REH and his Mother were still feeding off the property -so Lin Carter had him change the name and…first Clonan!

That’s ironic! Lin Carter-as-editor basically ensured that he would be overshadowed by the writers of the previous generation. Without that work, Carter might occupy the same niche space as Clark Ashton Smith.

However, even without creating a shadow to stand in, he was never going to be a great because he was so very adamant that Sword and Sorcery shouldn’t *mean* anything, or deal with serious themes. It’s a shame because when he goes into that territory – the Man Who Loved Mars, I think is an example – he can really do it. If only….

I think that if an Earth person went to another planet which had plants called “PletThethN’tchukha’a” but they looked like pine trees, our traveler would just call them pine trees for the remainder of the narrative. Doing so would make it readable.

At any rate I don’t get far through a book that makes me work so hard.

I desperately wanted to like Charles Saunders’ Imaro series, but I had to stop in the middle of every sentence and try to remember what an n’tembwe was in order for it to make sense. If he had just said “lion” “spear” “chief” etc. I could have devoured those books the same way I did the Conan stories, but it was too much of a chore and I put them down.

Yes, all fantasy and most SF is technically “in translation” anyway, so I think unfamiliar words have to justify themselves. Edgar Rice Burroughs got it about right in terms of frequency,e.g. jed and jedak, but though they added flavour, they didn’t really add meaning.

In your example, I might have humans use the term “squirm pines”, or something else a little evocative.

“He was a far better editor than author”

From reading some of his books I came to think that Lin Carter was held back as a writer by his own admiration of authors like Dunsany and Burroughs, and his simulation/honouring/evocation of their styles greatly hindered his own development as a writer. He certainly had many wonderful ideas, but it is undoubtedly that he loved those imaginary worlds and people who wrote them. In “Over the Hills and Far Away”, which was one of the last in Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, the sorrow with which he had to end the series could be almost physically felt, especially comparing to jubilation in the intro to Dunsany’s book at the beginning of the series.

Loved this series Harold. I will keep scanning shelves in the dusty second hand bookshops I frequent, hoping to pick on up.