The Aesthetics of Sword & Sorcery: An Interview with Philip Emery

The Shadow Cycles by Philip Emery (Immanion Press, August 2011)

This continues our interviews on “Beauty in Weird Fiction” with previous topics being:

- THE BEAUTY IN HORROR AND SADNESS: AN INTERVIEW with DARRELL SCHWEITZER

- THE BEAUTIFUL AND THE REPELLENT: AN INTERVIEW with CHARLES A. GRAMLICH

- DISGUST AND DESIRE: AN INTERVIEW with ANNA SMITH SPARK

- ACCESSIBLE DARK FANTASY: AN INTERVIEW with CAROL BERG

- GOD, DARKNESS, & WONDER: AN INTERVIEW with BYRON LEAVITT

Are you haunted, perhaps obsessed, with Sword & Sorcery?

Heroic fiction is infectious. Sometimes vicariously “being the hero” via reading is not enough to satisfy the call. Being compelled to write manifests next. Ghosts may be to blame. Robert E. Howard (1906-1936) is credited with originating the genre with his characters: Conan the Barbarian, King Kull, Solomon Kane, and Bran Mak Morn; in a 1933 correspondence to his friend and contemporary author, Clark Ashton Smith, Howard explained his interaction with the muse that inspired his Conan yarns.

‘While I don’t go so far as to believe that stories are inspired by actually existing spirits or powers… I have sometimes wondered if it were possible that unrecognized forces of the past or present–or even the future–work through the thought and actions of living men… the man Conan seemed to grow up in my mind without much labor on my part and immediately a stream of stories flowed off my pen–or rather off my typewriter–almost without effort on my part. I did not seem to be creating, but rather relating events that had occurred… The character took complete possession of my mind and crowded out everything else in the way of story-writing. When I deliberately tried to write something else, I couldn’t do it.’

‘I do not attempt to explain this by esoteric or occult means, but the facts remain. I still write of Conan more powerfully and with more understanding than any of my other characters. But the time will probably come when I will suddenly find myself unable to write convincingly of him at all. This has happened in the past with nearly all my rather numerous characters; suddenly I find myself out of contact with the conception, as if the man himself had been standing at my shoulder directing my efforts, and had suddenly turned and gone away, leaving me to search for another character.’

[Lord, G. (1976). The Last Celt: A Bio-Bibliography of Robert Ervin Howard. Hampton Falls, NH, Donald M. Grant Publisher, Inc., p57]

S&S has evolved over the last century. REH’s spirit, or the phantoms that plagued him, have inspired, or haunted, countless others. New voices and characters have broadened the scope, like Karl Edward Wagner’s Kane or Michael Moorcock’s Elric—perhaps even spawning contemporary Grimdark. Answering “what is” and “what is not” S&S is philosophically entertaining, but the scope of contagion is not the primary topic here. This is about the fans/victims who are infected by REH. Severely stricken artists, like Phil Emery, become so obsessed they go beyond writing S&S and write a doctoral thesis on REH’s writing (Revivifying The Ur-Text: A Reconstruction of Sword-&-Sorcery as a Literary Form; Loughborough University, 2019).

The Case of Philip Emery

Let us consider the case of Philip Emery (whose condition resembles the afflictions/abilities of Lovecraft’s Charles Dexter Ward and Richard Upton Pickman). Emery’s passion for expanding S&S is a wonderful journey, and his work is worth studying as well as reading for pleasure.

He lives just outside Newcastle-under-Lyme, on the outskirts of the Potteries (United Kingdom). He works as a freelance writer/lecturer, teaching creative writing for various universities, colleges, and educational organizations, and was an associate lecturer with Keele University for over twenty years. I first learned of his work Return of the Sword via Rogue Blade Entertainment’s Demons: A Clash of Steel Anthology, in which Emery’s “Fifteen Breaths” had a poetic, dreamy-weird style to it. Crossed his work again in RBE’s Return of the Sword and was completely taken with his “The Last Scream of Carnage” (notably the editor’s pick). It was again poetic and pushed the bounds of the genre. His gothic, steampunk novel. Necromantra was very enjoyable (reminiscent of Brian McNaughton’s style in the infamous The Throne of Bones—just replace McNaughton’s focus on “ghoul erotica” with “thaumaturgic conjuring”). Recently he published “Seven Thrones” in Parallel Universe Publications’ Swords & Sorceries: Tales of Heroic Fantasy Volume 2.

Emery’s experimental Sword & Sorcery adventure The Shadow Cycles (2011, Immanion Press) featured weird, poetic Sword & Sorcery. Now out-of-print, there is a possibility of a second edition with new material from Jason Waltz’s ambitious and innovative Rogue Blades Foundation publishing project at some point in the future. Waltz colorfully captures his emotions after reading Emery’s work:

“Wow. Well now that was quite the read, Phil. I am all at once congratulatory-confused-challenged. Point me to the nearest windmill and shout ‘Beware!” Jason M Waltz, RBE/RBF

Indeed, Emery’s writing is mind-bending. If you have not read it before, prepare to be mesmerized (or even infected). Emery’s The Shadow Cycles present a milieu in which all the suns/planets were flooded/swallowed by a tangible shadow, and magical forces allow limited teleportation from other realms to steer the fate of two remaining serpents which serve as vessels for humanoids: one, a petrified, floating dragon; and two, a leviathan on life-support. The latter is a wondrous, horrific landscape in which humans live in arteries filled with “tallow warts” and resonating with “meat echoes.” A few excerpts showcase his style:

“Again there is a different cold. Bleak. Vast. Filled with moans. The chamber stretches into the distance, and throughout that length, hanging from the vaulty ceiling, are the same fleshy stalactites that strew the labyrinths. Except these are longer. And from them hang bare bodies. Men. Women. Children. Moaning.”

“The tendril-things curl around their necks, holding them just above the floor. Others meander among them. Gazing up at them. Nudging them so that they turn slightly. Pinching them. Considering. Because these tendrils, unlike human umbilical cords, not only nourish but leach. They give life to the suspended ones but at the same time soften tissue, suck bone brittle – until the time is right.”

“Leviathan moves on through the wakeless sea and the dragonreme slips down its flank. Across its leagues of back a spine of bony spikes stab out. On each spike is impaled a torn, livid body, an oriflamme of skin and sinew. The spike bores through the small of the back and up through the belly, bowing the body. Arms and legs loll down but not their heads. There are no heads.”

Phil Emery is a natural fit for our interviews on the topic of “Art & Beauty in Weird Fantasy.” Let’s tap his mind on the aesthetics of S&S.

SEL #1: You have written on the evolution of Sword & Sorcery, summarizing its status:

“From the early 1980s until the late 1990s the genre or sub-genre known as sword-&-sorcery was largely moribund. The Tolkien-derived high fantasy novel, on the other hand, flourished and mutated into six, eight, ten-volume, or open-ended series. Even though the terms high fantasy and sword-&-sorcery are sometimes used interchangeably, sword-&-sorcery came to be viewed as an inferior, cruder form: rougher in style, more limited structurally, stunted in terms of character development, even morally questionable (rather than ambiguous).”

How S&S is evolving in the 2020’s? Any thoughts on the Grimdark craze?

PE: I suspect that how S&S is evolving is partly dependent on whether you see Grimdark as S&S. I recall a lengthy discussion on the Goodreads S&S forum a few years ago which touched on this. Certainly Grimdark recruits and amplifies some elements of Robert E. Howard’s aesthetic in depicting physical violence and certainly there’s the seeds of the moral ambiguity found in Grimdark in REH’s S&S – and there’s little doubt that if REH was writing now, and writing fantasy now, he’d probably be all over Grimdark. But…

Differing aesthetics can be seen simply as ways of being – or ways of dealing with the real world in such a way as to give it meaning – Japanese samurai and the medieval knight by all accounts had very developed aesthetics with elements of the metaphysical. Albeit their real lives were hard, bloody and almost always short, they had an access to an ideal which gave those lives, that reality, a kind of beauty. I’ve no problem with dark, no problem at all – and not much with grim for that matter. It’s more a matter of the kind of grim. A lot of Grimdark seems to emphasize the grim. A fashionable term at the moment is ‘dirty medievalism’: as in dirt, squalor, etc., equals realism. Or naturalism, maybe.

There doesn’t seem to be much of an element that Howard’s aesthetic contained: romanticism. And where gritty naturalism takes precedence can there still be a place for romanticism? Steve Eng notes that ‘an overriding mood in Howard’s poetry is one of romanticism.’ And Edward Waterman has commented on Howard’s affinity for romanticism. In fact it’s possibly the combination of romantic and Gothic influences, themselves historically linked, filtered through Howard’s highly personal if ostensibly commercial approach to writing which shaped his S&S.

I think that the trend toward naturalism and away from Howard’s romanticized aesthetic began even as early as Fritz Leiber’s Fafhrd and Grey Mouser stories, stories with more ‘human’ protagonists. It seems to me that this trend’s become ubiquitous in twenty-first century sword-&-sorcery and fantasy and represents part of a general migration away from alterity.

But, to reiterate again, perhaps the most important characteristic claimed for Grimdark is a marginalizing of the supernatural element. It seems not so much that the numinous is deployed sparingly (not necessarily a bad thing) but that it’s sidelined as just one story element among many, in favour of psychological complexity of character and realistically graphic violence.

All of which probably only partially answers your question about evolution – but I do wonder if the Grimdark tsunami couldn’t be compared with the cyberpunk explosion in the eighties. Eventually, its characteristics were assimilated into mainstream science fiction. Might be that will happen with Grimdark and S&S. Of course, this analogy is complicated by all kinds of literary and publishing and other nuances… Analogies always fall apart in the end…

SEL #2: You have a chapter dedicated on “Robert E. Howard’s Aesthetic of Violence.” Please summarize of what you learned. Pick an excerpt to discuss. Do you share REH’s aesthetic?

PE: Okay, you asked for it:

My preparation for writing The Shadow Cycles was to identify via two approaches essential elements in Robert E. Howard’s original sword-&-sorcery form. My intention was to set down a number of conceptual motifs partly through an instinctual or experiential method based on decades reading the form, and partly through a more formally analytical one based on that same reading but informed by literary critical knowledge I did not have when I first encountered it. In this way thirteen motifs were arrived at by the conflation of personal and critical perspectives. As I wrote TSC their non-definitive wording allowed me to view them as ‘live’ and ‘evolving’ rather than clearly-defined conclusions. These were:

- Sword-&-sorcery is intense. All else is subjugated to this effect

- Sword-&-sorcery is potentially amoral

- Sword-&-sorcery is the combination of violence and the numinous: a double-helix of violences which entwine around intensity

- Sword-&-sorcery eschews explicit development of milieu or character or concept

- Sword-&-sorcery is generally naturally a short story form

- Sword-&-sorcery contains an element of deathwish in its sensibility

- Sword-&-sorcery has a Chthonic sensibility

- Sword-&-sorcery has a potential element of tragedy in its sensibility

- Sword-&-sorcery combines explicit and implicit horror

- The Sword-&-sorcery protagonist is a loner – a figure apart or other

- Sword-&-sorcery addresses the irrational through the very fact of its connection with the numinous effect

- Sword-&-sorcery is about power

- Sword-&-sorcery is highly ‘visual’ (either through the presence or the absence of the visual).

So there it is: my ‘tarot’ of Howardian S&S. You might characterize tarot reading as intuition facilitated by symbol – visual symbolism in the cards, verbal symbolism in my thirteen motifs.

This would be some kind of epic interview if I was to go through my thoughts on each of the thirteen. But as an example, the double-helix mentioned refers to characterizing REH’s way of depicting violence into physical violence or kinetic violence, emotional or potential violence (the berserker rage his protagonists tend to experience conflates the kinetic and the emotional), and stylistic violence, in respect of Howard simply the power of his prose or poetry. The second strand of the helix refers to the ideas of the theologian Rudolph Otto, who broke the effect of the numinous into three components, which he collectively names the ‘mysterium tremendum’, these being ‘overpoweringness’, ‘energy’ or ‘urgency’, and ‘awefulness’ or ‘unapproachability’. My argument is that Howard’s most powerful sword-&-sorcery incorporates all three of these elements and that the stories which lack any of the three are less effective. It might even be said that these elements mirror the three Howardian technical violences. In fact, there’s an amplification of my thoughts on this in an essay entitled ‘The Problem of Tuzun Thune’ currently under consideration at The Dark Man.

Those thirteen motifs are still evolving for me – and because they’re couched in vague terms, someone could take them, interpret them differently, and produce S&S of an entirely different kind to The Shadow Cycles which would be just as ‘true’ to my perceived essentials of the Howardian form. They’re as much about what S&S might be as what it is. I hope to have a section called ‘Motifs of Storm and Shadow’ in any new edition which continues the process in a conflation of critical and creative elements. Actually I tried to do something more along those lines in the PhD thesis – that is tried to make it more akin to a metaphor than a simile, make the critical and creative parts more intimately connected – the critical is, after all, to my way of thinking, just another type of creativity…

But my long-suffering supervisors often reined me in when my artistic audacity (or idiocy?) threatened to take over…

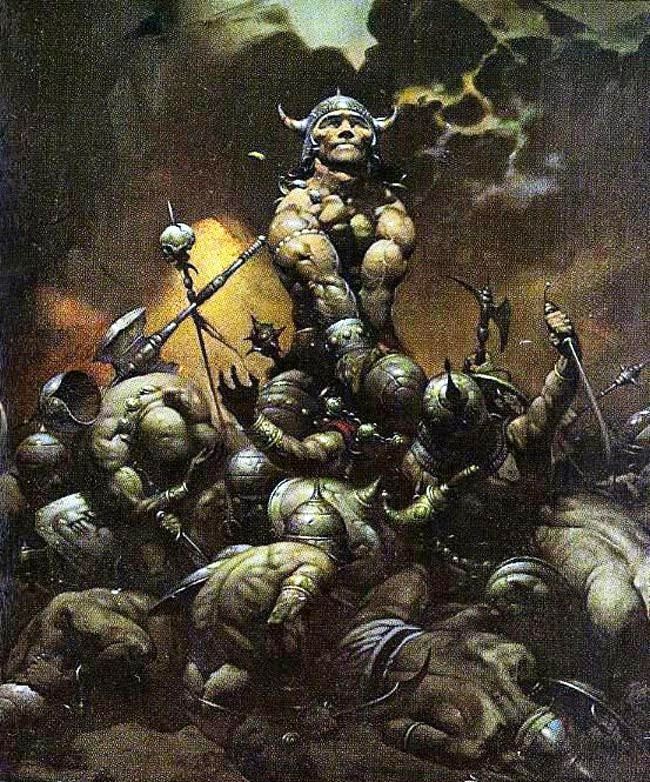

Around the same time, I wrote an essay which went more into the nuts and bolts of Howard’s prose style, entitled ‘Berserker Synecdoche: Howard’s Aesthetic of Violence’. This identified a set of techniques that favoured a tendency to sequence descriptive passages in a surprisingly consistent order, that order being general to poetic to specific and back to general imagery, and also argued that he tended to place such details in ‘relief’ above a vaguer background. (Take a look at those iconic Frazetta pictures – he employs the visual equivalent of this technique.) In his approach to describing the supernatural, I also noted that he’d sometimes use a kind of ‘virtual simile’ that conveyed emotion rather than visual precision. “She saw a great toad-like face, the features of which were as dim and unstable as those of a specter seen in a mirror of nightmare”, for example. (That’s from ‘Xuthal of the Dusk’. Remember my tarot motif, “Sword-&-sorcery is highly ‘visual’ (either through the presence or the absence of the visual”? You’ll find instances of this in kind of thing in The Shadow Cycles.) Howard’s technique seems to be remarkably varied and flexible and possibly only held together by his instinctive storytelling instinct. The essay was published in the 25th anniversary issue of The Dark Man Journal of Howard Studies. I’ve published pieces there before – really just as a way of saying thank-you to a writer who’s given me tremendous pleasure over the years.

Do I share his aesthetic? Put it this way: I think I’m in touch with it.

SEL #3: Your thesis is not just an overview of S&S, it also lays out your plan to renew the genre. How are you motivated to reshape S&S’s future?

PE: Oh dear. That comment about redefining the form at the beginning of the ‘Storm of Shadow’ essay appendixing the original Shadow Cycles edition! It was written some twenty years ago, long before the current resurgence of S&S, and certainly well before ‘Game of Thrones’ was a twinkle in Sky Atlantic’s eye.

This was before the green shoots of the revival began to appear, possibly a year or so later with the publication of Mike Chinn’s ‘Swords Against the Millennium’ anthology. But I still think, mind you, that the revisioning I set about was necessary for me as a writer. I’d felt the weight of my fantasy reading years was resulting in an object case of that old ‘law of diminishing returns’. The potential pitfall of ‘been there-read that’ is particularly tricky for fantasy genres where otherness is a crucial stock-in-trade. So any impression that I set out to single-handedly rescue or reshape S&S should be put to the sword – or maybe I should be too. I did, however want to bring a literary angle to proceedings. I’ve always read literary as well as so-called genre work, particularly the more experimental end of things, which tend more toward a ‘writerly’ rather than a ‘readerly’ approach – in other words asking the reader to work a little harder.

There never was a S&S equivalent to SF’s sixties new wave, and I feel that that kind of acceptance of experimentation isn’t so great these days. (How I’d have liked to see Burroughs (William) and even better Kathy Acker take on S&S.) I attended a writers workshop in London many years ago taught by Algis Budrys, and one piece of advice he gave was that no matter how well ploughed the generic field you’re ploughing, always try for something extra – something fresh. Always give the work your best effort. Push that damn envelope. It’s a sentiment echoed by the novelist and screenwriter William Goldman in his memoir ‘Adventures in the Screen Trade’. And believe it or not, I do get inspired by some of the ideas to be found in literary theory. In fact it’s technical challenge that tends to motivate me more than anything. I once wrote a story concerning a blind and deaf ‘Samurai’ and the challenge of telling the tale from his view-less-point was what most interested me. (‘Nightdweller’ appeared in ‘Abyss and Apex’ web magazine and then in my Immanion Press collection ‘The Celt in the Machine’. One of the meanings of that title is throwing a spanner into the works of orthodoxy – a celt being an ancient kind of, well, spanner.)

So there was no grand barbaric ambition to ‘come hither and tread the jaded genres of the earth beneath my postmodernist feet’… Fun as that would be… Just the intention to write as best I can and prod the occasional envelope along the way. (I remember when ‘The Last Scream of Carnage’, a kind of oblique prototype of TSC was published: one review commented, “the most impressive thing to me is that the story exists”. I liked that.)

SEL#4: Do you consult or perform tarot readings? Ever draw/design your own tarot cards? Are you inspired by Tarot card art?

PE: I certainly learned how to lay out and read a tarot spread when I was writing TSC. But I’ve already covered some of the connections of the tarot to The Shadow Cycles above, so perhaps I can here talk about some of the other ways I find a use for it?

Early in The Shadow Cycles, Sstheness uses a kind of tarot pack to predict the arrival of the Phoenix Prey – an early signalling of a suggested tarot card reading dynamic for the story. Each chapter or scene might be thought of as one card – one unit. Reading a tarot layout has similarities to reading a story, generic or otherwise. In TSC significance is not always handed to the reader overtly, but needs to be interpreted. So the tarot provides a useful metaphor for a reader interpreting or filling in gaps of plot or character motivation or missing generic elements. And as I’ve said it implicitly licenses the reader to dwell on individual cards/narrative units more than might be the case in more conventional fiction reading. Not every story can be read at expresso-speed, and the necessity to slow down and ‘smell the narrative coffee’ isn’t necessarily a fault in the writing. The taut sentence/clause/phrase style of TSC adds extra emphasis to this appeal to a more considered reading tempo, as are the measured focus on moment-by-moment and the degree of choral-style repetition.

All this is admittedly simply an extension of existing narrative techniques. In fact an example exists in the Howard story ‘Black Colossus’. In a long paragraph Howard introduces princess Yasmela with a typical prose-poem style general description before focusing in on a precise and ominous moment in time. Only in the following paragraph is the ‘shapeless shadow’ which menaces her revealed. The sequence builds slowly, layering on detail after detail.

One thing I mention in the thesis is TSC’s attempt to ‘convert understanding into effect or resonance rather than communication’ – it’s another try at moving the emphasis away from plot – which is not to say I gratuitously tried to confuse the reader. In fact, I went to considerable lengths to offer good traditional storytelling aid. As an example, take the battle scene on the galleys where most of the principle characters meet. So, four or five characters to keep track of in a chaotic scene, albeit I had introduced each of them separately earlier:

They’re all afraid; the oarcrew; the Sword-Mariners, men and women in jerkins and breeks of tight otherworldly mail; the oarsmasters, one to each ship; the helm, one to each ship’s rudder-vanes; even the navigators. But the fear of the first ones who turn and look up is different from the fear of the others. It beckons their eyes. Then the first cries and mutters of astonishment and awe go out and all the rest of them, every last one on every ship, looks up.

A flame flickers down between the stars, arcing and falling, a blue coma waked by red and white and yellow flurry.

The first choice of the Phoenix.

Some of the Sword-Mariners of the first dragonreme to reach him send down a rope and haul him up out of the sea. It takes seven, nine to pull him aboard. A cuirassed giant. Dark-maned. Taller and wider than any Mariner. And the scabbard at his side holds a sword twice the length of their own, even if it had not been straight but arced like theirs. Its pommel is a smooth, perfectly round ruby.

He rests on hands and knees on the deck for a moment, breathing deep. He pulls the great white pelt on his back more firmly across his shoulders and stands.

The first of the five to plunge out of the sky.

This is Gemmored, the swordsman.

I don’t even name him here, but those key physical details: the size, the mane, the sword, the white bear pelt, hopefully jog the reader’s memory. It’s an old, old technique: Homer uses it in The Illiad – key phrases or details, epithets which help his audience keep track. And this is a book – the reader has control just like someone doing a tarot reading. Both can pause, go back, consider. This is one of the ways TSC utilizes the tarot connection, probably the most significant use: structural – there’s license to pause and recap much more than a mainstream contemporary novel tends to give. Some will object to that kind of license, that particular ‘celt’ thrown into the works of orthodox storytelling ‘good practice’. But the reading process can be demanding and complex even for the most straightforward of prose. Robert Graves’ book The Reader Over Your Shoulder, albeit a little dated now, anatomizes this thoroughly. You could say that I’m simply acknowledging and using this.

Of course a move away from plot compromises the usual levers of expectation and anticipation, but the overall premise of a group of characters recruited Seven Samurai / Magnificent Seven style to aid in fighting a war, and the looming nature of that war I hope compensates to some degree. Often writing decisions are more ‘swings and roundabouts’ than hard rights and wrongs. I think that there’s a useful distinction to be made between premise and plot – both’re straight-forward enough in TSC to hopefully allow more attention to rest with the style or effect without entirely losing track of both the former two. TSC is almost entirely chronological.

SEL #5: Despite your admiration for Howard’s works, to me, your poetic style seems more reminiscent of REH’s contemporary: Clark Ashton Smith. In a 1930 letter to H.P. Lovecraft, CAS described his strategy of using aesthetics to heighten the reading experience of his weird works:

“My own conscious ideal has been to delude the reader into accepting an impossibility, or series of impossibilities, by means of a sort of verbal black magic, in the achievement of which I make use of prose-rhythm, metaphor, simile, tone-color, counter-point, and other stylistic resources, like a sort of incantation.”

Comment on the differences between CAS weird-S&S vs. REH’s approach, and how cadence can be employed to affect beauty or horror?

PE: On CAS, for whom I know we share a great admiration: my diction is much less Latinate than Smith’s. Certainly, The Shadow Cycles’ prose is sonorous and rhythmical, but the cadences are (deliberately) much less smooth than Smith’s. The complexity of some of my sentences owes more to my pushing at the visual potential of S&S – a slight extension or ‘weighting’ of detail. (Just slight in the main – though I did consider early on having an entire chapter consisting solely of naming all the precious stones in the roof of Dragonkeep…) I appreciate that the reader needs to acclimatize to the style, but hopefully no more than someone reading an eighteenth or nineteenth century novel has to. The style of TSC isn’t intended to pastiche, or worse parody either Smith or Howard. I was going for something much more subtle: using those tarot motifs, those units of Howardian sensibility, as a launching point to develop a style that embodied those original S&S sensibilities. So you don’t find Howardian pace or Smithian flow in TSC – but I do think my rhythms and pronounced focus in The Shadow Cycles prose achieved almost a ‘holophrastic’ effect here and there, as if the whole book might be present in an individual sentence?

This attempt at concentration is actually mirrored within the story when it’s revealed that a gesture or a single act or even a word uttered or not uttered might decide the outcome of the war. If a reader picks up on this then everything that happens after this point has a potential significance beyond itself. None of this duplicates the Howardian brand of intensity, but I hope it ‘echoes’ it in its own way. And both REH and CAS worked largely with short fiction – due to its length, The Shadow Cycles has a variety of cadences – even within the Nightmare Cadre dream sequence written in pseudo-verse the different characters have different rhythms which mirror their personalities. I aimed for a style that was neither modern nor archaic, but suggested both. For me there’s nothing that kills otherness in fantasy more stone-dead than modern slang; that general push toward naturalism, I suppose.

Regardless, I certainly feel TSC is the culmination of my decades of writing. The history of The Shadow Cycles in its various versions is too convoluted to go into. But the original doctoral-intended Shadow Cycles was actually my first book but the one I wrote second! The whole Shadow Cycles project had been in my mind since the early seventies, characters, plots, imagery, etc. Yet I knew I hadn’t the ability to tackle it then. I think that most writers who begin young have all the creative energy in the world, but that dwindles over time – whereas in compensation experience builds on experience. There comes a time, and the writer recognizes it, when those two elements come into a balance and that’s when their best work happens. So I wrote Necromantra first in preparation for that balance.

You asked about the differences between the Howard approach and the Smith approach. I suppose we should first explain that I recognize not one kind of S&S but several. There’s Howard’s Ur-text, the hard-driving vivid gothic adventure kind with hardy powerful protagonists confronting the supernatural which set the agenda. Next came the Howardian Epigones who followed closely in his wake, then what I call Neo-S&S which developed the ‘tarot’. Fritz Leiber with his Fafhrd and Gray Mouser tales would probably be the first and one of the best known of this ilk, notably adding irony to the mix. Clark Ashton Smith is probably who comes most strongly to mind when I come to my category of Weird-S&S. Though Dunsany pre-dates him.

Weird-S&S is a kind of S&S that shares the irony of the Neo category, but usually its protagonists are by no means extraordinary physical specimens – in fact often they don’t survive the stories they feature in. And another difference is, certainly as regards Clark Ashton Smith, less of a concern with plot and more with a more poetic register of language. (It’s probably the most direct instance of creating beauty-in-horror; although I’d say that any well-crafted depiction of horror or the horrific is a thing of beauty – the definition of beauty being another envelope I’d want to push.) These categories are no doubt contentious to some, but they’ve helpfully informed my own S&S. They help me zero in on what I’m trying to do with any particular project. I’d definitely put my ‘Arabesques from the Edge of Time’ sequence and my ‘Geis and Trolls’ stories in the weird-S&S bracket.

SEL #6: Similarly, how can one craft poetry (or abstract prose) to be awe-inspiring (truly magical) yet remain accessible (too weird)?

PE: Can you be too weird?

Seriously, I think we’re back to the balance between communication and effect. More than once I’ve read Dunsany’s The King of Elfland’s Daughter and ‘lost’ myself in those cadences. I’ve reached the bottom of a page and thought: “hold on, what happened on that page? I’ll need to look back and check. But this is Dunsany – I’ll be inclined to forgive him just about anything. (Mind you, is this something that requires forgiveness?) The same with Greer Gillman, or the later Alan Garner (particularly ‘Red Shift’). It’s easy to lose plot, so a balance is always sought for narrative fiction. Formal metered narrative verse does tend to edge a reader closer to a concentration on effect rather than plot, but only slightly. The Rhyme of the Ancient Mariner is a piece that seems almost to poise itself fifty-fifty, helped by the straight-forwardness of the premise I suspect. I think.

Ballads in particular seem to touch on something elemental in the reader but are grounded in plot. Even a much larger narrative verse such as Glynn Maxwell’s haunting ‘Time’s Fool’, several hundred pages of terza rima modernizing the Flying Dutchman story, has to find a balance. I think Samuel Delany in ‘The Jewel-Hinged Jaw’ argues that there’s really no such thing as a division of form and content. How you write something is part of what it is. So if the magical effect is accessible in that it has an effect, perhaps that’s enough. I also think that for something to be profoundly numinous it needs some degree of Otto’s ‘unapproachable’ – surely it can’t be fully known and still weird? I believe the magic lies in the gaps – the writer’s art is to ‘scaffold’ those gaps, cast the right shadows…

SEL #7: CAS was a poet, illustrator, and sculptor; many others interviewed on this topic of “Beauty in Weird Fantasy” have other artistic talents beyond writing. Do you practice other arts (necromancy counts)? If so, can we share them (i.e., images of fine or graphic art) or mp3s (of music). If not, which artists/pieces inspire you to write?

PE: I pretty much concentrate on the writing – but I do spread myself pretty wide. Besides prose fiction and verse and non-fiction, I write playscripts and graphic novel scripts. I’m presently working on a number of graphic novels with a tremendously talented artist, Toe Keen, based in Spain. And a live Zoom readthrough of an absurdist black comedy, ‘Decaying Circle’, took place in May.

SEL#8: Any new works you can discuss? More Shadow Cycles?

PE: “Never shares a big bed with once,” opines the Gray Mouser in “Trapped in the Sea of Stars” – but I probably won’t return to The Shadow Cycles directly, and can’t imagine writing anything quite so layered and allusive and ambitious again – the completion of TSC signaled a new stage of my writing life where I’m now writing what I want to, not what I need to. But the agenda developed in writing the book and the thesis will inform the aesthetics of much of my future sword-&-sorcery* A short story, ‘Twilight’s Four’, presently without a home, focuses on the tarot motif “Sword-&-sorcery addresses the irrational through the very fact of its connection with the numinous effect” – in other words madness.

There’s a series entitled ‘Knights Incognitus’ the first story of which was scheduled for Rogue Blades’ aborted ‘Assassins’ anthology – but that’s more science fantasy than full-on S&S. There’s also a series called ‘Jack o’ Wraiths’, capitalizing on my fondness for the British folktale, but again too gentle to be properly called S&S. However I’ve begun work on a series of shorts under the collective title of ‘Unsheathings’, playing on the warrior-poet trope, which is probably the closest thing to that Howardian Ur-text. (Friends of mine highly qualified in Iaido, the Japanese art of sword drawing, are giving me a little basic training as part of my research.) The ‘Seven Thrones’ in the recently published second volume Swords & Sorceries anthology from Parallel Universe is one of these

And while I did say I wouldn’t be returning to The Shadow Cycles directly, I do happen to have something like twenty-five thousand words of notes left over from that thesis which I’m reworking into a verse-essay along the lines of Alexander Pope’s verse essays – but without the heroic couplets. I refer the reader back to my earlier comment about audacity and idiocy…

S.E. Lindberg resides near Cincinnati, Ohio working as a microscopist by day. Two decades of practicing chemistry, combined with a passion for the Sword & Sorcery genre, spurs him to write adventure fictionalizing the alchemical humors (under the banner Dyscrasia Fiction). With Perseid Press, he writes weird tales in the same bloody vein (Heroika and Heroes in Hell series). He co-moderates the Sword & Sorcery group on Goodreads, and invites all to participate. He enjoys studying Aikido and creates all sorts of fine art in the family workshop.

A really interesting read.

‘I think that most writers who begin young have all the creative energy in the world, but that dwindles over time – whereas in compensation experience builds on experience. There comes a time, and the writer recognizes it, when those two elements come into a balance and that’s when their best work happens.’

Yup. That seems to be the consensus. I’d like to think it isn’t true, but…

I’m kind of ambivalent about Grimdark (despite having read very little) because I think its attempt to give the fantasy genre a more realistic veneer hides a basic lack of imagination; we’re still talking about the same old tropes. Leone did much the same thing with Westerns, but Leone had more visual flair.

‘There never was a S&S equivalent to SF’s sixties new wave.’ True – but it’s interesting how one author – Moorcock – produced both.

]

Re CAS. I’m a big CAS fan. Earlier you mentioned how Grimdark tends to ignore the supernatural element. It strikes me that with CAS it’s the other way round – ‘Sorcery & Sword’ might be a more appropriate description. Even then, burly, sword-swinging barbarians are comparatively rare and usually the outcome is the exact opposite of what might occur in the equivalent Conan story – ‘The Maze of Maal Dwebb’ being a case in point.

Glad you enjoyed it. Nice comments. I agree also about CAS….there does seem to be a continuum of S&S tales with varying Sorcery elements. CAS is definitely heavy on the Sorcery side….more “earthy” Grimdark seems to be on the opposite generally.