Some Words That Must Be Said

100:

Well, hidey-ho there, friend! Let me ask you something. Have you or a loved one ever been writing something – say, a novel, or a short story, or heck, even a sonnet– and found yourself apprehensive about the dialogue to come? Or have you ever felt the reverse, an all-encompassing need to document the details of every character’s chit-chat? If so, you might be on the Dialogue Malappropriation Spectrum, or DMS for short.

Golly, I’m not sure. Can you tell me more? Continue from 180.

I most certainly do not! Continue from 320.

I do. I really do! Continue from 440.

You again? Listen, I thought I made it clear I’m just here for the stories and gaming stuff. Continue from 230.

110:

Ah, yes, silent DMS, or SDMS for short. SDMS is the quiet and lonely home of three classes of DMS, all of which involve an avoidance mechanism originating either somewhere in a writer’s hippocampus, some unrelated ganglia or other, or even a misfiring gland or two. Whatever the exact cause, the writer experiences one (or more!) of these three indications:

Dialogue Calcification: The writer substitutes a paragraph of dense prose where they actually know very well that a line or two of pithy dialogue would be more fitting, evocative, and brief. This can be difficult to diagnose from outside a writer’s own mind, as test readers, editors, and agents might simply think the writer is a generally stilted and awkward sort of person, when in truth this indigestible block of prose is actually light beams and literary rainbows that have been transmogrified into their current state.

Creeping Grimdark: You don’t mean for the tone to be so oppressive, but somehow you have an inordinate number of characters that grunt in place of speech, are more than a little taciturn, and too often substitute steely glances for opinions. While this might well be you as a writer channeling the years you spent being raised by the gardener, the soup cook, and the head laundress, it might also be that your characters are not intended to be speechless and grim, but that you are afraid – yes, afraid! – to let your characters speak because of problems in your literary past that you don’t wish to repeat.

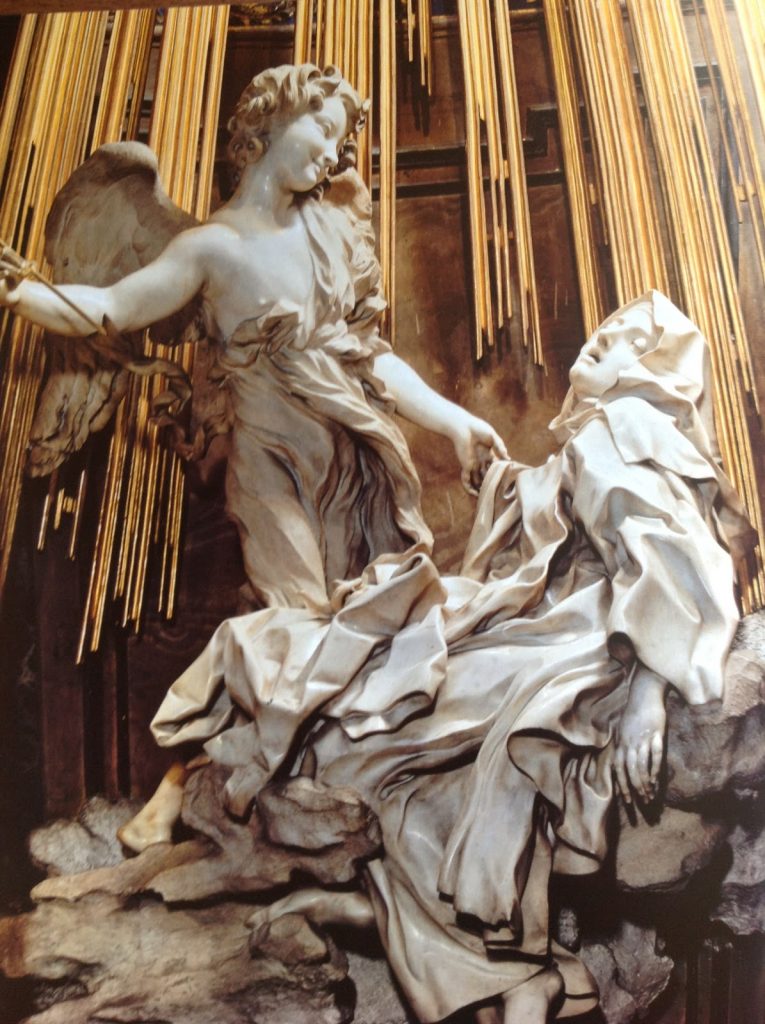

Bernini’s Syndrome: You’ve got dialogue aplenty, so how can SDMS apply to you? Well, Friend, if you find yourself crafting your dialogue with excruciating care, roughly carving it out of a metaphorical block of mental marble in stages, then shaping it word by agonizing word until it is a wonder for all to behold, you might just have SDMS. If your dialogue takes a simply incredibly long time to create, take heed! Dialogue, like actual speech, is a thought-by-thought process, not really a word-by-word one.

Golly, Dialogue Calcification is exactly what I do! Continue from 210.

Hmm. Grimdark… hmph! Continue from 400.

I must confess, I bring forth my dialogue in a manner not unlike that worthy sculptor Bernini, and a great burden it is, too. Continue from 190.

I actually think I might be the more chatty sort of DMS. Continue from 200.

130:

And so, satiated at last, you watch as your hundreds of progeny burrow down into the earth from whence you came, to live a life among the softly glowing cathedrals under the mango tree roots, passing around the tales you have taught them, tales of garden parties, and scheming, hungry possums. Of unrequited love and chances lost. Of one unknown figure’s desperate, last minute race by horseback under the moonlight, to speak at long last the words they had so yearned to say. Tales of a heated verbal exchange. And, at last, the tale of unexpected mercy, mercy your progeny cannot hope to experience themselves. And so they burrow alongside and then underneath a strange and unexpected lockbox they find in the earth, through which the scent of polished silver gently wafts. And they wait, counting the years till they – and the lockbox, too – will emerge once more into the light.

That was an unexpectedly touching ending. I’m tearing up, here. Continue with another blog post.

180:

I’d be glad to tell you more, Friend! Dialogue Malappropriation Spectrum is a range of behaviors that can afflict writers in different ways, each with their own treatment options. Now, it might sound scary, but being on the DM Spectrum is more common than you might think, especially when you consider how hard to diagnose it can be. Some professionals believe that all writers can be placed somewhere on the spectrum, and that’s okay, Friend! We’re all in this together, right? Right!

Okay, I guess learning more about the signs of DMS can’t hurt. Continue from 430.

I write lots of dialogue, and this still isn’t ringing any bells. Continue from 310.

190:

Treating Bernini’s Syndrome can be a lengthy process, but generally a pleasant one. The main challenge you’re actually grappling with, Friend, is that you’re not writing dialogue like you speak dialogue. Hopefully. Except for that spring morning three weeks ago when you chanced upon your true love outside the mango orchard, and constructed awkward sentences in front of them for a time, and they waited patiently, watching you with that gaze that seemed to hold both understanding and sublimated desire, until the moment was ended by the arrival of the souse chef, who handed you that bushel of shallots to prepare for the midday meal.

In any case – but quite profoundly in that specific one – speaking more freely is an asset, and your characters would agree. To construct dialogue in a more liberating fashion, I recommend the Daedalus Method. When trapped in his own labyrinth, did he construct a Mig-29, or a Swedish Viggen, or a simple Boeing 737? Heck not he did not, Friend. He went with the expedient solution of wax- and wood-based wings and flew that particular coop.

In your situation, it’s probably going to look more like you sitting in a coffee shop, or lurking at social events – like an certain upcoming garden party – and simply listening to other people converse. Coffee shops are good for this sort of thing because the coffee – or other beverage, really – gives you license to sit in one spot and overhear the conversations around you. As long as you don’t make extended, unblinking eye contact with your subjects, you should be fine.

There’s a certain rhythm to the speech you’re likely to hear. A cadence, if you will. One person generally turns the conversation over to the other with some regularity. Run-on sentences are out, too. Fragments? Everywhere, but don’t overdo it. And, unlike in your actual attempts at human connection, be sure that your speech doesn’t consist of just fragments, or you’ll veer into another category of DMS altogether!

This did the trick, thanks! Continue from 500.

I think I need to go back and review the other types of Silent DMS as well. Continue from 110.

200:

You know that uneasy moment after you ask someone how they’re doing, and they launch into an extended catalog of their exact status? That moment when you realize that the small, social nicety you’ve offered, expecting a bland non-response, has somehow unleashed a torrent of unsolicited internal assessment on their part? That is what some writers inflict on their readers (and even more frequently, on their editors). This is caused by the over-expressive side of the spectrum, known as Chatty DMS, or CDMS. CDMS mainly takes on the following two forms:

Heliotropic Bloat: This form of DMS makes each page contain fewer and fewer words by the expedient of fluttery dialogue flitting between two or more characters like a possum at a garden party, leaping from branch to branch overhead, gorging itself on cicadas. While it seems to be indulging in a nutritious meal, enjoying the bounty nature has provided, it soon finds itself engorged with an unexpectedly high volume of chitin and wings, and rather less so the life-giving goo which each cicada only provides a dollop of. And so, like your manuscript after a full draft of this, the possum finds itself unable to fully escape the attentions of the orange-plumed hawks which seek to cull their numbers, and you find yourself providing a life-preserving stomach-pumping procedure on a possum fallen into the punch bowl instead of talking to your truest love, who steps away uncertainly, into the arms of Morgan, who has naught but a smirk for your kind-hearted efforts. Thus it is with your manuscript, which should have been kept lean, and now, after a critical assessment by your editors, requires invasive dialogue extraction and a prolonged period of recovery.

The Oroborous Complex: Your characters are talking, all friendly like, and advancing the story nicely through demonstrations of personality and tone. It is a thing of beauty. And then, just as the conversation begins to wind down, bam! It starts meandering without a clear transition, revving back up to full power, but now with a less defined direction. But before you can isolate a section to excise, it segues back to another important point, and then veers in some non-euclidean direction and is mysteriously off-track once more, a cycle without apparent end.

I’m Heliotropic. My dialogue is fluffy and bloated, there’s no question about it. Continue from 120.

I frequently suffer from conversations lasting 4 or more pages, and need to see a doctor right away. Continue from 240.

I think I need to see the silent side of the DMS spectrum before deciding what ails me. Continue from 110.

My dialogue isn’t so much chatty or spare as… something else. Isn’t there some middle ground of dialogue woe I could visit? Continue from 330.

210:

Dialogue Calcification can be cured by a number of techniques. For example, during a conversation with a friend or loved one you could work in what one calcified character says to another, and see how that loved one responds. If you find that this makes your writing fill up with characters saying things like “Are you feeling all right?” or “I’m calling the police now,” you may wish to try the next technique, which involves taking isolated walks outside and actually speaking dialogue out loud. You might be surprised at how constrained our speech can be. A writer can easily write dialogue that contains tongue twisters, strange asides, and all manner of curlicues, when in reality speech is far more spare.

A key point is being somewhere alone. This isn’t an acting exercise, but being alone keeps you from repeating that incident from a few weeks ago, as you wandered behind the cider presses near the southern orchards, trying desperately to put your feelings about a certain special someone into words, and were overheard by another certain someone. Discretion is key here, just as it was then!

The reminder is painful, yet appreciated. I will do this! Continue from 500.

230:

I can respect that, Friend! And yet, deep down, I detect a certain longing to get out the fountain pen that a particular person once gifted you in your youth; a pen with which you composed odes of love and longing, but were never brave enough to give to the postman for delivery. With this pen, Friend, you could take up fresh paper, and perhaps brave the inner storms that have so long plagued you, and find yourself on the shores of a new life. A life of precious, life-affirming fantasy or science fictional prose. Prose that might, if given voice, turn the head of a certain someone, even now.

Uh, sure. I’ll try that. Continue from 500.

You’ve seen the truth of my soul! Continue from 500.

240:

Just as a possum has a distinct beginning and a distinct end, so too, must a conversation. As any cicada who has ventured within one can attest, the path through any given possum can meander greatly, but, whatever wonders are contained within, they must serve to extract life-giving nutrients from the visiting cicada before taking its leave. So, too, must literary cicadas, which are topics important to plot, setting, or character, pass through literary possums, which are conversations, giving up their cicada-juices, which is plot-stuff. I hope that is clear, Friend, because I’m not keen on repeating it!

As a more concrete example, keep in mind that, in real life, at least half of all conversation is setting up your inevitable need to extricate yourself from it. So, too, in writing. Your characters need not feign heat exhaustion, like you were forced to do last Tuesday at the green grocer’s, as you, the writer, can have any number of circumstances interrupt a conversation that has served its purpose. Simply have an inciting event kickstart the next phase of the story, in the same way that the souse-chef’s daughter would have done last Tuesday, had you not attracted attention by pretending to swoon and collapse into the arugula. Set up your exits before you need them, so that you aren’t required to perform embarrassing literary antics on the page.

When you put it that way, it all sounds so easy. Except for that cicada bit, which was gross. Continue from 500.

300:

Whoa, there, Friend. I’m not saying there’s anything wrong with it, per se. It’s just a bit far from my remit, you know? I’m just here to talk about DMS, and you seem to be doing just fine doing… that.

Continue from 130.

310:

That’s just swell, Friend! Not everybody writes on the DMS, and if that’s not you, then congrats! Some people find that natural-sounding dialogue, that suits the voice of their character, the needs of the plot, and is true to the setting is their default writing style. Perhaps you, like these other writers, find that in real life you are similarly adroit in social situations. For example at garden parties. You – like these other, hypothetical writers – have no problem walking boldly up to the person who has so captured you heart and expressing your true feelings.

Continue from 510.

320:

Well now, let’s just examine that fact, Friend, and do a full diagnosis, shall we? It’s nothing to be ashamed of! After all, it’s a mark of sophistication to be able to engage in healthy self-critique. Remember, writers don’t emerge from the ground after a 17-year subterranean existence, like the cicadas did at a certain garden party last Saturday. And if they had, these emerging writers, communicating in sonorous waves, might be excused if their particular hum was less practiced than their fellows. Indeed, it might well take the first of their precious hours of chirping to catch the bright eyes of that certain someone on a nearby leaf, the way you caught the eye of a certain someone at that garden party. And in that moment, both might feel a wave of relief – nay, a swelling of gratitude – toward whomever might tell them how to best hone their verbal skills. And that someone might well be me, even though the garden party in question was last Saturday, and you stood, struck dumb with uncertainty, while Morgan– yet, that Morgan– moved in with a ready quip, and, high above and unseen, a cicada watched helpless and forlorn as their chosen chose another, and left them bereft and alone.

Okay, okay, maybe I could hear a bit about this DMS. Continue from 180

I’m still not getting this whole DMS thing. My dialogue is fabulous! Continue from 310

330:

There are many strange and disturbing form of DMS, and those on this particular spectrum are only sometimes aware that things are amiss. This is because there are also less severe positions on the DM spectrum, where writers – termed high functioning writers – can get along in a general sort of way, but find their characters sometimes subject to strangely specific tics and verbal oddities. This is a partial lest of the sort of oddities I mean:

Tagosis: The small phrase that interrupts speech on a page and explains how a character says it is often referred to as a tag. Common tags are said, asked, and explained. These are virtually invisible to readers, Friend, and serve in almost all circumstances where a tag is needed. Less common tags are called, exclaimed, or something a bit like that. Stronger or more descriptive, but not enough so to draw attention to themselves. Mildly pathological tags are such things as ejaculated, conjuntified, propounded, and the like. Things only get more dire from there. These are all forms of Tagosis.

Roget’s syndrome: The choice of verb or adjective is a large part of a writer’s style. This must be constrained on one side by repetitiveness, and on the other by utter incomprehensibility. If you’ve ever found your characters using odd words for common ones, you need to ask yourself if that is a legitimate choice, or an example of Roget’s syndrome, where you use ever-more-obscure words for ever more common concepts, and then excuse it as a character trait when you, as a writer, actually can’t help yourself.

Pronounal Subtractivism: If you’ve ever hesitated to write as a gender you are not, or even as a gender you are, because you don’t feel you can speak in a proper voice for a person of that gender, you might find yourself diagnosed with Pronounal Subtractivism, wherein a writer removes one or more dimensions of a character because of their gender, and then replaces that lost dimension with the gender in question. This almost guarantees a stereotyped character, and is unfair to one and all.

Geolocationalisms: It was once all the rage to faithfully depict regionalism in a character’s speech. Nowadays, not so much. It nearly always comes off as demeaning and mocking, like your first, early attempts to speak to the Souse Chef in the accent of northern Boise when you’d grown up among the mango orchards of southern Saskatchewan. It wasn’t appreciated then, and your characters will have no better luck with their own attempts.

Prometheism: Like geolocationalism, this is an attempt to put the character into a given social class at a particular time, as demonstrated by their peculiar slang. Just remember that slang is a highly prized social artifact, and is jealously guarded by those who create and use it. When you or your characters attempt to take and use what is so clearly not yours or theirs, the consequences can be dire. This would explain why your attempt to blend in with the scullery maids last Friday was such a disaster, as were your overtures to the stable hands Tuesday last, and gardeners the Wednesday before that.

Clariphycosis: Some characters serve no other purpose than to speak to the reader while pretending that the reader is merely overhearing them speak to another character. When they do so, they usually relate something this other character probably already knows, but the reader almost certainly does not, but should. Like the time you overheard the Stable Master and the Senechal going just one more time over their plan to steal the estate’s silver before it could be sealed in a lockbox and buried somewhere on the grounds before the war broke out. Both of these two knew the plan, and yet they spoke it out aloud just one more time, to their eventual consternation. The outcome for your characters will be little better – if less graphic – so don’t do it. In fact, you may wish to examine if this character is actually needed at all, like the way the estate decided it really didn’t need a Seneschal.

Lordy, these are insidious! What to do? Continue from 410.

400:

The cure for Grimdark, friend, is to acknowledge that your character isn’t really taciturn. It’s more like being constipated. Now, I know what your thinking, and that isn’t the solution here any more than it was that unfortunate stormy evening last fall.

No, the cure for Grimdark is a quiet, introspective assessment of what, exactly, is the problem you wish to avoid in your dialogue which is making you avoid dialogue altogether. This is sometimes an issue of being too self-critical, and backing away from the memory of dialogues past, whether real or literary. Like the time you tried to express your feelings to your secret love whom you could just barely see through a curtain far above the gardens where you were laboring, only to have the curtain swept aside by the malodorous broom-mender’s apprentice, who confessed their love in return.

The point is that what happened in the past can only be avoided if we learn from it. Or if we set up a complex sequence of interactions placing the consequences of our mistakes into contact with someone who is smitten with said consequences, and arrange for them to meet in a way that requires our mistakes to disavow us, and choose the other, and thus never to be seen again.

So… open up and just do more dialogue, no matter how painful the learning process is? Exactly. Continue from 500.

410:

If you’ve been laboring underground for, say, seventeen years on a manuscript, and have just begun to tunnel your way toward publication, it might take a while to recognize the actors in this new, sun-washed environment. Instinctively, you may wish to start climbing at once, chirping as loudly as you can that you have a finished manuscript. Most of the chaos around you is, you will soon learn, an irrelevant garden party. But in the branches above lurk even less savory situations, some of which combine sharp senses with sharper teeth, and back them up with twisty dark insides.

The point, if it was not yet obvious, is that most of the milder forms of DMS can be located by a trusty literary sidekick called an Editor. Now, were you a cicada, this editor might gently nudge your pronunciation of a particular part of your chirp, thus enabling you to lure more desirable mates closer. Or, in the most extreme cases, draw away a predatory possum, offering themselves up so that you may yet succeed. In this instance, the literary possum is your dialogue, which does its job, but in a manner painful and all-consuming to your editor. Though they may exist for just such a sacrifice, you really should express your undying gratitude to their progeny before they tunnel back into the ground for the next seventeen years.

Wow, that’s both a terrible and an inspirational metaphor. Continue to 500.

430:

Writing dialogue is a natural and beautiful part of the fiction writing process, but it has enough complexity to cause even dialogue-normative writers occasional issues. So how do you know if you’re on the spectrum, and not just having performance issues related to temporary anxiety or uncertainty?

In general, if you find yourself in the best possible writing scenario, with characters you know and relate to, a plot that is moving forward nicely, and a setting you’ve already established, writing dialogue is just an extension of the loving relationship between a writer and their manuscript. But there are two main warning signs that you may actually be on one position or another on the DM spectrum.

The first sign is hesitation on your part. Now, Friend, beginning dialogue can sometimes feel like striking up a conversation in the real world with the girl or guy that has struck your fancy, am I right? But unlike in the real world, this hesitation shouldn’t stop you from starting right in. Unlike in the real world – for example at that garden party last Saturday, where you couldn’t work up the courage to say so much as a howdy-do, and the object of your hopeless infatuation drifted off with your arch-rival, Morgan– starting dialogue in your manuscript should be no harder than any other literary effect.

The other common sign you’re DMS is that your pages are downright fluffy with conversating characters. Like those cicadas that soon swarmed a certain garden party last Saturday, these characters appear on every surface of your manuscript, their chatter ceaseless and, when written out and studied, basically devoid of any content that advances the plot or reveals character. Unless your characters are all desperate arthropods, am I right?

Thanks for reminding me about that painful incident with Morgan; it has haunted me this entire week, and I suspect is is a sign of something more serious. Continue from 110.

The droning of those cicadas was indeed onerous, and yet familiar from my writing. Continue from 200.

How did you know my manuscript was arthropod erotica? Continue from 300.

It’s not so much that I write too much or too little dialogue. It’s more that it’s just… off somehow. Continue from 330.

440:

Glad to hear you’re so willing to be honest with yourself, Friend. Alright, now for the straight dope. There are three types of Dialogue Malapproriation, called Chatty DMS, where you just can’t seem to stop writing dialogue, no matter what the cost to yourself or your loved ones, Silent DMS, where you want to write dialogue, you should write dialogue, but you can’t make yourself write dialogue, and Mild DMS, which is everything in between that haunts your past dialogue and current love life.

Chatty sounds about right. Continue from 200.

Even my disorders are bland. Mild DMS for me, please! Continue from 330.

Silent… hmm… Hmrrr… Continue from 110.

500:

Well, Friend, that about wraps it up! I hope you’ve learned a valuable lesson today, and are now well on your way to a life free of the scourge of DMS in all of its forms. Remember, I’ll be in touch!

Uh, thanks. Bye? Continue with another blog post.

510:

Because of your highly developed sense of verbal interchange you avoided the situation where you watched, helpless, as your despised rival, Morgan, made their own move, seizing the moment while you dithered. And I’m very happy to remind you that, with all of these things being the case, you engaged Morgan in a battle of verbal combat, and came out victorious. Indeed, your dry wit and piercing observations were as charming as they were effective, disarming Morgan, enthralling your true love with their lack of pettiness, and sending the watching crowd of party-goers into a polite pitter-pat of applause as Morgan fled the field of battle. Your finely-honed skill at constructing dialogue has paid off handsomely once again!

Thanks, I’ll be off, now. Continue with another blog post.

This is great post. I’m still chuckling about the Morgan incident. Well, I am one of many suffering sDMS.

Glad I could help, Friend!