Deadly Archeology on Alien Planets: “It Opens the Sky” by Theodore Sturgeon

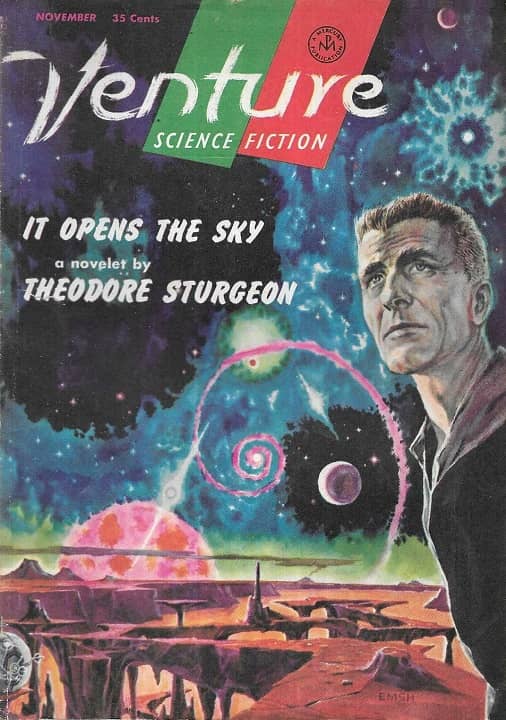

Venture Science Fiction, November 1957. Cover by Emsh

In this series of essays I have been taking a close look at stories I find interesting, trying to figure out how they work. So far the stories (and one poem) I have discussed are pieces I find particularly good – and this is hardly surprising, as surely it’s better to know how and what good stories do than weak stories. But this time I’m taking a look at a story I enjoy, but that I also think deeply flawed. Why? Partly because it’s by Theodore Sturgeon, one of my very favorite writers. But also this story seems very Sturgeonesque – so I hope that I can understand better what Sturgeon tries to do in his most characteristic stories, and why sometimes even while he does what he wants to do the story qua story doesn’t wholly work.

My favorite Sturgeon stories are “The Man Who Lost the Sea,” “A Saucer of Loneliness,” and “And Now the News …”. There are other very good and very well-known stories by him: “Baby is Three,” “Mr. Costello, Hero,” “Bulkhead,” “Affair with a Green Monkey,” “And My Fear is Great …”. And there are early stories that seem less truly characteristic of the mature writer, though they are still well-regarded: the SF Hall of Fame story “Microcosmic God,” horror stories like “It” and “Bianca’s Hands,” the possessed bulldozer piece “Killdozer.” I love a late ‘40s sense of wonder thing, “The Sky Was Full of Ships,” but that too is not core Sturgeon. But there are a few stories from his peak period, the 1950s, that have the emotional punch, and the moments of utter beauty, of the best of his work, but that for one reason or another don’t stick the landing. “The Golden Helix” is one. “The [Widget], the [Wadget], and Boff” is another – a novella that for half its length bids fair to be as good as anything he ever wrote, but which can’t quite find its way to a satisfactory resolution. And there is “It Opens the Sky,” the story I mean to treat here, which has pages of sheer loveliness, passages of great power, and a message that is Sturgeon at his most tender and optimistic. It is a story that brings me to tears, and yet frustrates me.

“It Opens the Sky” appeared in the November 1957 issue of Venture Science Fiction. Venture was a companion to The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, specifically intended to be the “pure SF” outlet, as opposed to F&SF’s admixture of Fantasy, SF, and marginal stuff. Venture also published some work that was (or so it seems to me) intended to be particularly challenging, especially on sexual themes, but also sometimes politically. Venture only lasted 10 bimonthly issues in 1957 and 1958 – this was a bad time for the magazines, with the collapse of distributor American News Company in 1957. Those issues were pretty strong, on the whole, and a Best of Venture compilation would be a good book. The magazine was revived for six further issues in 1969 and 1970, built around a conceit of a “Complete Novel” in each issue. (These “novels” were in the 35,000 to 45,000 word range.) I don’t find those issues as good as the earlier incarnation – the best story in them is probably one of Tiptree’s better early stories, “The Snows Are Melted, the Snows are Gone.”

What is “It Opens the Sky” about? (It’s about 17,000 words, somebody will say!) It’s about a man named Deeming, by day a hotel clerk, but by night “Jimmy the Flick”: a con man, a thief, whom we meet choosing a widowed woman to victimize – following her into a bar, talking her up, seducing her, getting her clothes off then absconding with her dead husband’s watch and her money. And he worries about “the Angels” – a group of seeming “supermen” who have replaced police, and who gently work at preventing crime and reforming criminals. But for Deeming (or “Jimmy”) the Angels just take the fun and freedom from life – they “close the sky.”

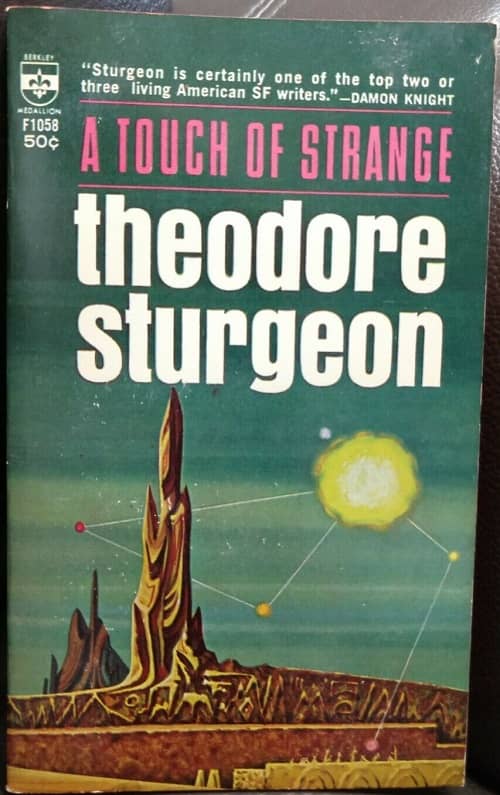

A Touch of Strange (Berkley Medallion, October 1959). Cover by Richard Powers

Then he gets an offer – from Richard Rockhard, a very rich man who needs the help of a con man, a man who is willing – nay, desperate! – to defy the Angels. Rockhard’s son (Don) has no interest in his father’s business, and he’s become an archaeologist, and is on the track of an important discovery. His father has supported him, but he doesn’t want more help – except that what he’s doing is on a proscribed planet, Revelo – the Angels won’t let people go there, because it is a source of the terribly dangerous and addictive drug yingyang, that makes people superintelligent and strong and kills them. Deeming takes the job, which is to get to Don Rockhard and slip him a way to escape the planet. The first stop is Angel HQ on another planet, Ybo, to steal a navigation “coin” that will get him to Revelo. And before he can get to the building, he meets a girl named Tandy, and he also meets an Angel. And in the process we learn that only men can be Angels, though Tandy wants to be one. She works in the HQ building, and soon Deeming has her helping him find the room he wants. But of course he can’t just blithely take a coin for proscribed planet, so he shoots the Angel guarding the proscribed room, and, as he says sadly to Tandy, “You know I have to kill you,” and he does what he has to do.

Then it’s off to his ship, and after shooting the Angel who has found the ship he escapes to a normal planet, aware that the Angels will surely be paying extra attention to all the proscribed planets. But once there he learns two things – that Richard Rockhard has been arrested for financial crimes, so both any additional money owed Deeming and any obligations Deeming owes to Rockhard are moot; and that the Angels have followed him to this planet. But he ends up going to Revelo anyway, and he finds Don Rockhard’s ship, but not the man. The ship does have a credit chip worth a fortune, plus a course coin to another proscribed planet, a place where you can get a complete and secure new identity. And when Don returns to his ship and finds Deeming, Deeming is presented with a decision – keep the money and the chance at a new identity, which means killing or marooning Don Rockhard; or letting him go and being marooned himself.

And then … the shock twist ending, which had probably occurred to a lot of you. Deeming gets ready to shoot Don … and then Don is gone, and Deeming is asking himself “Why didn’t I shoot?,” and an Angel appears. Deeming resignedly gives up – “go ahead and arrest me, turn my brains to yogurt.” And the Angel asks him: “Why didn’t you shoot Don Rockhard? Why did you let the Angels back on Ybo live? Why did you only knock out Tandy instead of killing her like you said you had to? Why did you mail the watch back to that woman on Earth?” … and Deeming has no answer — but the Angel says “We’re not arresting you, we’re recruiting you.”

So … I will confess right now, in a few places, “It Opens the Sky” brings me to tears. But it shouldn’t! It really isn’t that good a story, taken as a whole! So – because Sturgeon is such a great writer it occurred to me to ask – what is he doing that works so well? In his greatest stories it’s more clear in a way – the utter desperation of MacLyle in “And Now the News …” is perfectly believable. The agonized loneliness of the woman in “A Saucer of Loneliness” … The triumph amid tragedy of the astronaut in “The Man Who Lost the Sea” … (“God,” he cries, dying on Mars, “God, we made it!”)

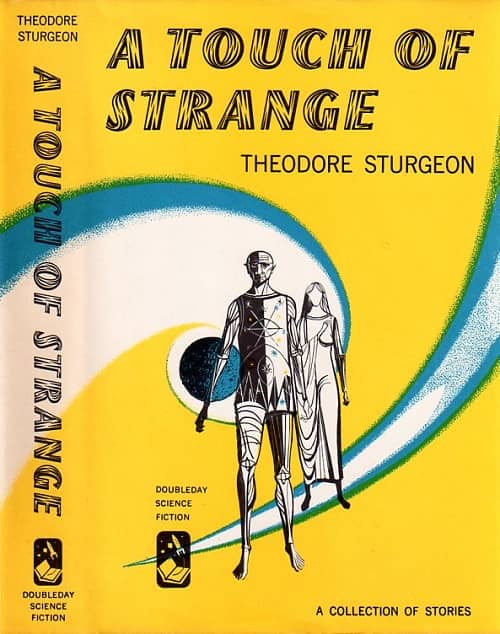

A Touch of Strange (Doubleday, July 1958). Cover by Joseph Mugnaini

Those stories are widely acknowledged to be among the greatest in SF history. No one says this about “It Opens the Sky,” and no one should. It has only been reprinted in Sturgeon’s own collections, A Touch of Strange and The Man Who Lost the Sea. But Sturgeon has a similar message in most of his great stories, and even in the failures he succeeds at making us care, making us love.

What’s wrong with “It Opens the Sky”? Basically – it’s a rickety and unbelievable construct from the getgo. The opening, on Earth, introduces an unlikable but also pitiable main character … a thief and seducer, in rebellion against a quasi-government we don’t understand. Sturgeon’s writing here is slick in a style he could always adopt, familiar from detective fiction of that era. Each next plot development strains belief, but until the end always within the expectations of pulp plotting. So, we as readers buy silliness like the field polarization that defeats the Angels’ protective screen around Revelo; and we buy the even sillier notion that that polarization would work only one way. (That’s how “Don Rockhard” could get in but not back out.) We also buy – but of course not really, we know it’s dumb as it happens – the relative ease of his penetration of the building on Ybo to steal the navigation coin to Revelo. And we don’t question – or we do, but we let the question pass – the way the Angels are always there when the plot requires, but somehow not there when Deeming is getting away with the critical steps of his plan.

Then there are the final revelations: the whole thing was a setup all along. There never was a Richard Rockhard, nor a Don Rockhard. There never was an archaeological mission to Revelo (instead, Revelo is the planetary base of the Angels.) This has all been a rather elaborate test of Deeming – because the Angels believe he is a potential Angel. It’s been a dangerous test – he could have failed at any step. This whole thing seems terribly overelaborate (and scary,) so it’s hard to believe in, but I’m inclined to give it a pass because it’s entirely in the service of Sturgeon’s moral.

So – a really quite implausible story all the way through. What’s to like? The first answer is that in the reading Sturgeon mostly papers over the silliness so that you’re just carried along. (Lots of writers do that, to be sure – but Sturgeon did have the pulp writer’s gift, of slickness, urgency, drive. We don’t always think of it in the context of Sturgeon’s career – but he really could do that, he just could do so much more!) So even though, say, a close look at Richard Rockhard’s story might raise questions, as we’re reading it, we’re happy to buy it. And so on.

But that’s a minor thing. What’s major is what the story is about, and how Sturgeon tells us that, and makes us believe it. What is the story about? It’s about something that may be Sturgeon’s most central theme. This theme is, I think, loneliness – and the cure for loneliness, which is simplistically “love,” but more truly is community – and community based on love. All kinds of love. Eros (sexual love), to be sure, but also, perhaps more importantly, Philia (brotherly love), and of course, most of all, Agape, which after all is the love for everyone – for your community, yes, but also for a belief that your community extends indefinitely. Sturgeon, it seems to me, grounded his idea of Agape in this sense in a combination of all three of those kinds of love – for him, I speculate, Eros was – or at least could be – an expression of Agape.

This can be seen in his greatest stories – in “And Now The News …” MacLyle is destroyed by his too complete identification with – love for – a community that wouldn’t love him – or anyone – back. In “A Saucer of Loneliness” the girl is isolated partly because she seems singled out as (perhaps I stretch a point here) part of a broader community than Earth people are ready to accept. “Mr. Costello, Hero” is about a man with an instinct to create “community,” but without love. “The Man Who Lost the Sea” is about a man who dies as isolated as possible from his community – and in so doing celebrates his community’s achievement (“We made it!”)

The Man Who Lost the Sea (North Atlantic Books, January 2005). Cover by Paula Morrison

And “It Opens the Sky”? This story is completely about community – indeed, an interstellar community. And one based on love, or at least on kindness – the Angels’ fundamental credo is “people must be kind to each other.” Is that a sappy or jejune or simplistic philosophy? It doesn’t have to be, and Sturgeon manages to sell it.

A lot of this comes through via the characterization of Deeming. He’s supposed to be a bad guy – a con man, a victimizer, out for his own self, his desire to be under an “open sky.” But – maybe we don’t notice it the first time through – he’s never mean. Even as we witness his initial crime – even before realizing he returns the watch to the widow – we can see that he is nice to her all along. He hopes to get her into bed in 90 minutes but instead listens to her for two and a half hours. And so on — every time he has a chance to hurt someone he backs off. Some of this is a bit artificial, but it’s all in pursuit of Sturgeon’s message.

Then there’s the girl, Tandy. (To notice this is cheating maybe – but Tandy is the name of one of Sturgeon’s daughters. (He later used it in another piece, “Tandy’s Story.”)) The whole first interlude with Tandy just glows – and Tandy glows, the story says so. Sturgeon could portray love as well as any writer, and Tandy as presented loves and is lovable. She also wants to be an Angel, but only men can be Angels. (A detail I thought dated and a bit unfair – but, arguably, important to the story.) We believe, right away, that Tandy is the woman for Deeming, if only he can be worthy of her. This is sheer romanticism, but, again, Sturgeon makes it work.

Still, as ever, what works best is words. The title is key – “It Opens the Sky.” The whole metaphor – how Deeming desperately needs an “open sky” – freedom, choice. And so he spends his life trying to get around what he thinks is “closing” his sky. But he learns – “the sky – your sky – has always been the limit.” To open the sky is to open it for everyone. If someone else is constrained by a closed sky, so are you, if you have to live with them. And we all have to live with all of our fellows. I’m not making my point, and I think that’s because I’m not Theodore Sturgeon. Sturgeon – even when not fully on his game – showed us – showed his readers – that love, that community, that kindness opens the sky. And that when your neighbor, whether it be Tandy, or a green monkey, or MacLyle, or a girl singled out by a flying saucer, or an abandoned Irish girl, is confined by their sky – so are you. And when he makes me feel this, he brings me to tears. And it works even when the rest of a story’s armature is as rickety as in this story.

Rich Horton’s last short fiction review for us was Winter Solstice, Camelot Station, by John M. Ford. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

“The triumph amid tragedy of the astronaut in “The Man Who Lost the Sea””

Ah, Rich, I see you agree with my positivist interpretation of Sturgeon’s masterpiece!

I am willing to give this story a try — in part because I enjoy how SF deals with anti-heroes.

You say you’re reviewing this story because it’s flawed, and then imply that Sturgeon stories are always flawed. Is that what you intended to say?

As I read “It Opens the Sky” I thought the story was flawed too. And I often think of Sturgeon’s stories as flawed. That his ambitious and very creative ideas don’t always unfold smoothly. But then I got to thinking, maybe we’re not thinking like Sturgeon, that he’s working on some other kind of storytelling logic we can’t see.

This story is as ambitious as anything Bester wrote in the 1950s. And it has the kind of space opera flavor Delany established in the 1960s. There’s a lot going on in “It Opens the Sky.” So why do we think it flawed?

The story made me tear up in places too. How can a story that moves us be a failure?

My disagreement with the story, its flaws, so to say, was the Mission Impossible plot that happens so fast, with every obstacle so easily overcome. And I didn’t want Deeming/Jimmy to turn out good.

Like you say, it strains our belief time and again. But then, maybe that’s our problem. There’s quite a lot of inventive world-building in that plot. Basically, I felt the story promised the weird perversity of “Fondly Fahrenheit” but somehow redeemed Vandaleur and his crazy android.

I agree that Sturgeon’s common preoccupation is loneliness and love and that’s what drives this story too. But isn’t it what messes up the story for us? Aren’t we the flawed ones because we don’t want to accept Sturgeon’s sermon?

I know this is perverse, but I would have been happier if Deeming is caught for being caring, and then destroyed viciously by the angels. Isn’t that sick? I considered the story flawed because it didn’t end like Alfred Bester would have written it.

Maybe if I could believe what Theodore Sturgeon preached, it wouldn’t be a flawed story.

No, I didn’t mean in any sense at all that “Sturgeon stories are always flawed”. Stories like “And Now the News …” and “The Man Who Lost the Sea” are nigh perfect.

(More later about your other interesting suggestions!)

So, first, at the beginning I thought Deeming would find a way to overturn the “oppressive” rule of the Angels. That was the “template” plot of Golden Age era SF, right? I agree that Bester — the Bester of, perhaps, “5,271,009” — would have found a more cynical ending.

That cynicism wasn’t in Sturgeon. Sturgeon believed in his vision of community. But, indeed, in this story the utter benevolence of the Angels (supported by the implausible drug yingyang) is hard to truly believe. That is a weakness. So the more tragic stories like “And Now the News …”, “A Saucer of Loneliness”, and “The Man Who Lost the Sea” (each of which ends with the death (presumably) of the protagonist) are more successful.