Vintage Treasures: The Past Through Tomorrow by Robert A. Heinlein

|

|

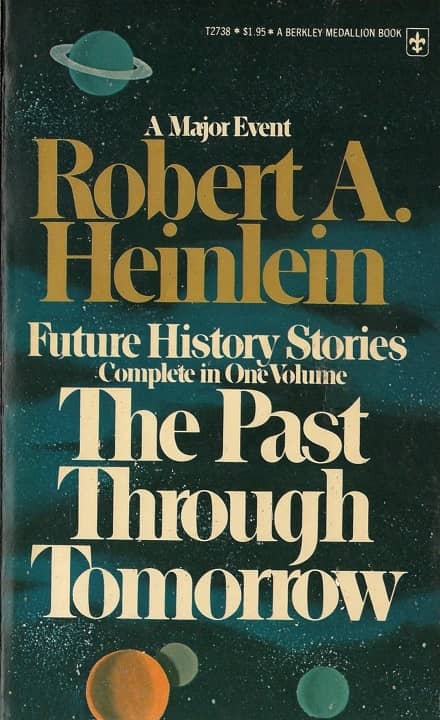

The Past Through Tomorrow (Berkley Medallion, January 1975). Cover uncredited

I’ve never been a big Heinlein fan. Not my fault. I enjoyed Starship Troopers well enough, but the next two novels I tried — The Moon is a Harsh Mistress and especially Friday — I bounced off pretty hard. I never tried again.

It didn’t help that I made most of my discoveries through short fiction in those days, and Heinlein almost never showed up in anthologies. Sometimes editors would apologize for omitting him, admitting (with some frustration) that they just couldn’t get the rights to the Heinlein tales they wanted. The problem was that by the mid-70s Heinlein was a star, the top-selling author in the field, and his entire short fiction catalog was locked up in his own bestselling collections.

I read collections, of course. Lots of them. But the seminal Heinlein collection, the one containing virtually all of his really important short work — including classics like “The Roads Must Roll,” “Blowups Happen,” “The Man Who Sold the Moon,” “Gentlemen, Be Seated,” “The Green Hills of Earth,” “Logic of Empire,” “The Menace from Earth,” “If This Goes On —”, and the short novel Methuselah’s Children — was the massive The Past Through Tomorrow. And that 830-page beast was just a bridge too far for a traumatized veteran of the first 100 pages of Friday.

[Click the images for Heinlein-sized versions.]

The result is, of course, that when I talk about really important 20th Century SF writers — which is kinda my thing? — I never mention Heinlein. Nope, nope.

But there’s been enough distance with my early failures with Heinlein now, not to mention a growing awareness of a big hole in my SF education. And I find myself increasingly curious about what I missed out on by not reading Heinlein in my youth. Besides a bunch of right-wing libertarian politics, obviously.

I picked up The Past Through Tomorrow recently, and I was impressed all over again at just how many true SF classics are packed within its pages. I can almost forgive its length, given that it contains 21 stories, three novellas (“The Man Who Sold the Moon,” “Logic of Empire,” and “Coventry”) and a complete novel, Methuselah’s Children. The stories within were published across four decades, from 1939 to 1962, first in John W. Campbell’s Astounding and later in places like Argosy, Blue Book, The Saturday Evening Post, and Scientific American.

Here’s the complete Table of Contents.

Introduction by Damon Knight

“Life-Line” (Astounding Science-Fiction, August 1939)

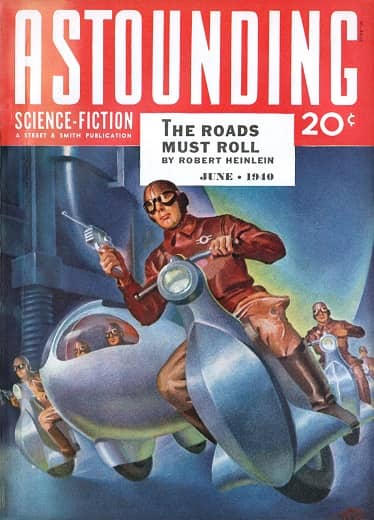

“The Roads Must Roll” (Astounding Science-Fiction, June 1940)

“Blowups Happen” (Astounding Science-Fiction, September 1940)

“The Man Who Sold the Moon” (The Man Who Sold the Moon, 1950)

“Delilah and the Space-Rigger” (The Blue Book Magazine, December 1949)

“Space Jockey” (The Saturday Evening Post, April 26, 1947)

“Requiem” (Astounding Science-Fiction, January 1940)

“The Long Watch” (The American Legion Magazine, December 1949)

“Gentlemen, Be Seated” (Argosy Magazine, May 1948)

“The Black Pits of Luna” (The Saturday Evening Post, January 10, 1948)

“It’s Great to Be Back!” (The Saturday Evening Post, July 26, 1947)

“—We Also Walk Dogs” (Astounding Science-Fiction, July 1941)

“Searchlight” (Scientific American, August 1962)

“Ordeal in Space” (Town & Country, May 1948)

“The Green Hills of Earth” (The Saturday Evening Post, February 8, 1947)

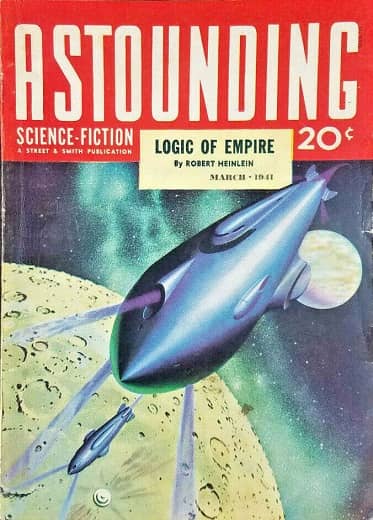

“Logic of Empire” (Astounding Science-Fiction, March 1941)

“The Menace from Earth” (The Magazine of Fantasy and Science Fiction, August 1957)

“If This Goes On —” (Astounding Science-Fiction, February 1940)

“Coventry” (Astounding Science-Fiction, July 1940)

“Misfit” (Astounding Science-Fiction, November 1939)

Methuselah’s Children (Astounding Science-Fiction, July-August 1941)

Robert A. Heinlein was one of Campbell’s most famous discoveries, and certainly the one that Campbell was most proud of. Alec Nevala-Lee, when discussing his groundbreaking non-fiction book Astounding: John W. Campbell, Isaac Asimov, Robert A. Heinlein, L. Ron Hubbard, and the Golden Age of Science Fiction, said, “Heinlein was the author Campbell was waiting for,” and I think that’s precisely right. Heinlein’s first published story was “Life-Line” in the August 1939 issue of Astounding; more rapidly followed and within a year Campbell was lauding Heinlein in his editorials as “a major science fiction writer.”

|

|

|

Astounding issues with Robert A Heinlein cover stories: June 1940, March 1941, July 1941. Covers by Hubert Rogers

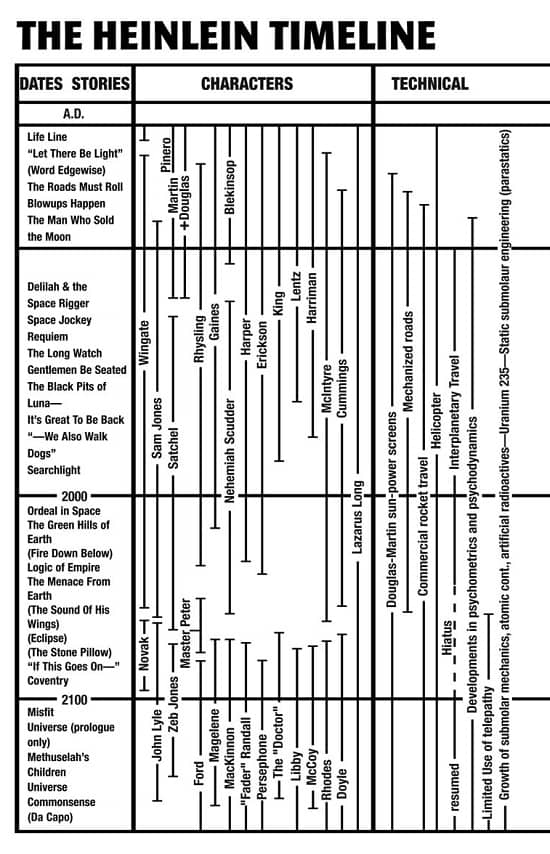

Robert A. Heinlein didn’t create the Future History (that distinction is usually given to pulp writer Neil R. Jones, whose popular Professor Jameson tales appeared in Amazing Stories in the early 30s), but John W. Campbell coined the phrase in Astounding to refer to the ambitious and wide-ranging vision of the future Heinlein was creating, brick by brick, in his early stories. Nowadays the phrase has become so closely associated with Heinlein that “Future History” defaults to an entry on Heinlein in Wikipedia, one that begins this way:

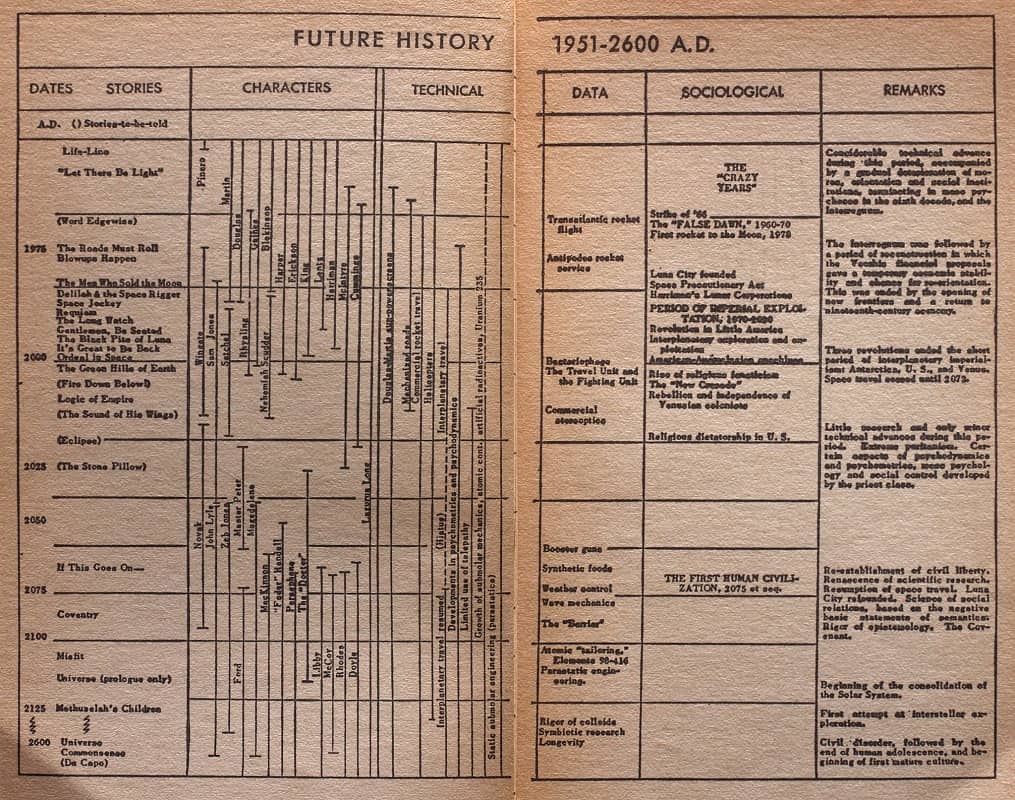

Future History is a series of stories created by Robert A. Heinlein. It describes a projected future of the human race from the middle of the 20th century through the early 23rd century. The term Future History was coined by John W. Campbell Jr. in the February 1941 issue of Astounding Science Fiction. Campbell published an early draft of Heinlein’s chart of the series in the May 1941 issue.

Heinlein wrote most of the Future History stories early in his career, between 1939 and 1941 and between 1945 and 1950. Most of the Future History stories written prior to 1967 are collected in The Past Through Tomorrow, which also contains the final version of the chart. That collection does not include “Universe” and “Common Sense;” they were published separately as Orphans of the Sky.

Groff Conklin called Future History “the greatest of all histories of tomorrow.” It was nominated for the Hugo Award for Best All-Time Series in 1966, along with the Barsoom series by Edgar Rice Burroughs, the Lensman series by E. E. Smith, the Foundation series by Isaac Asimov, and The Lord of the Rings series by J. R. R. Tolkien, but lost to Asimov’s Foundation series.

Campbell’s chart of Heinlein’s Future History tales has been updated and expanded many times over the decades. Here’s a version that covers most of the stories in The Past Through Tomorrow (click for more legible version).

And here’s the more detailed version that appeared in The Man Who Sold the Moon.

The Past Through Tomorrow was published in hardcover by Putnam in 1967, and reprinted in paperback by Berkley Medallion in 1975. The paperback version is 830 pages, priced at $1.50. The cover artist is uncredited.

See all our recent Vintage Treasures here.

Well, I also had an unusual introduction to science fiction in that Heinlein was largely absent. I did come across a few short fiction pieces, and it was hit and miss with those. When Gollancz reissued The Past Through Tomorrow in 2014, I finally secured a copy and set out to finish it, which I did, about five years ago. But alas, 2016 was too late to start reading Heinlein in earnest. I don’t see why the early stories made such a huge impact. I guess you had to be there. Oh, some of them were good—”Universe”, “Coventry”, “It’s Great to Be Back!”, “The Green Hills of Earth”, and probably others. But for every one of those, there was another where the portrayal of women made me roll my eyes. And oh, how he loved military protocol and business wrangling and talky stuff like that. I sat through two novel length works that are part of that compendium—If This Goes On, which I think is expanded from Astounding, and Methuselah’s Children, but both failed to excite any interest in his free-standing novels, even though I do have some of them in the house.

Piet,

I wonder about the same thing — is 2021 simply too late to become a Heinlein fan, even for readers of my generation? If that’s the case (and it might well be), then Heinlein is destined to be forgotten in one to two decades, tops. I think that will come as a shock to the die-hard Heinlein fans, of whom there are still plenty.

I wouldn’t be too surprised. I wonder sometimes if any of the 20th Century SF writers I do love will survive. Certainly the Weird Tales triumvirate (Howard, Lovecraft, Aston Smith). Octavia Butler maybe, Ursula K. Le Guin. Philip K. Dick. perhaps.

Others?

Read a generous selection of the stories that were being published at the same time those early Heinlein stories were, and you’ll see why Heinlein’s made such an impact.

Thomas,

I think that’s exactly right. Heinlein is best viewed in context. He’s a fine writer, and no argument.

I’m a huge Asimov fan, but his flaws as a fiction writer were considerable. Even with the small amount of Heinlein I’ve read, it’s clear to me his gifts as a writer were superior to Asimov. But I loved Asimov’s short fiction, warts and all.

“a traumatized veteran of the first 100 pages of Friday”

Oh, amen to that.

LOL. It was a good 15 years before I tried Heinlein again after that.

If you’re willing to give another short Heinlein novel a go, try Citizen of the Galaxy. This one exhibits many of his strengths and few of his weaknesses.

rrm,

I am, and that’s a great suggestion. I wrote about ORPHANS OF THE SKY a few months back:

https://www.blackgate.com/2021/02/21/vintage-treasures-orphans-of-the-sky-by-robert-a-heinlein/

and in the comments Thomas Parker recommended Double Star, The Door into Summer, and The Puppet Masters. I wanted to read some of Heinlein’s short fiction after ORPHANS, but now that I have I admit I’m curious about DOUBLE STAR and CITIZEN OF THE GALAXY. For one thing, they’re short, easy reads.

Thanks for the rec!

Double Star is my favorite of RAH’s adult novels (among the juveniles I will defend Have Spacesuit, Will Travel against all comers – you’ll have to pry my Ace paperback copy from my cold, dead hands) because – in addition to being a gripping, ripping yarn – it displays a quality that was not prominent in most of Heinlein’s other work – compassion.

I must admit I’m curious about it for a much more superficial reason… as I was completing my ASTOUNDING collection, I found Kelly Freas’ cover for the February 1956 issue, with the first installment of DOUBLE STAR, both gorgeous and instantly compelling. John Campbell’s story teaser was also intriguing. It’s not just that I want to read DOUBLE STAR, I want to read it in this magazine, with Freas’ iconic illos.

This cover is vastly superior to the one on my SIgnet paperback, a rather ugly green abstract.

When I was in high school, the thrift store where I bought all my used paperbacks got a gift from the gods – someone sold them a boatload of Astoundings from the 50’s, which I of course promptly snatched up. (What did they cost me? A buck or two a piece, I think. !!!) So when I read Double Star, I had the tremendous pleasure of reading it as it was originally published, on that wonderful-smelling paper with the original illustrations and Campbell’s cunning blurbs – the whole package. It’s still one of the great reading experiences of my life.

Is there anything that can compete with the literary discoveries of our teens? Your description is exactly how I remember reading DUNE, and FOUNDATION, and LORD OF LIGHT (minus the magazines).

Reading in my teens was also a more social experience than it is for me today. I was part of a small group of sci-fi fans in high school who were constantly trading paperbacks back and forth, telling each other “You HAVE to read this!” We all went to movies together, including the original STAR WARS trilogy. When Star Wars: Attack of the Clones was released 25 years later, we all flew to California so we could see it together.

I have a vivid memory of, the summer after second grade, sitting out on the front porch one day and reading Dad’s copy of Red Planet from cover to cover, so Heinlein is pretty foundational to me. These days, I recognize his flaws (and especially the way he got … weird in his last couple of decades); and if I’m going to reread anything of his, I’m much more likely to just pick up one of the juveniles. I’ll second the recommendation for Citizen of the Galaxy, which might be my favorite; I’m also a fan of Space Cadet.

It’s funny — it wasn’t until I was an adult, reading a plot summary for RED PLANET. that I realized I’d read it as a child. A couple of scenes were vividly stuck in my memory, but both the title and author had long vanished from my memory.

And you read it after second grade?? That’s impressive!

Yep, unless I’m misremembering by a year or something. But I’m pretty sure that was the case. Sadly, I didn’t keep extensively detailed documentation of my childhood reading, so I’m not sure if Heinlein came before or after I first read John Christopher’s Tripods trilogy.

All of Dad’s old Heinlein paperbacks (plus his copy of Dune and a couple of Arthur C. Clarke books) I kind of appropriated when I moved out after college, and they’re still on my shelf. I was surprised when I realized that a lot of the juvie paperbacks (including that copy of Red Planet) were actually reprints from the early 70s and so were, in fact, younger than I was at the time.

John, it’s funny you mention “bouncing off” Heinlein’s The Moon Is a Harsh Mistress. I started that novel some years ago and . . . O, the shame of it!—stopped reading about halfway through and never went back. A page-turner this one isn’t. Please understand that I never intentionally quit on a book; it’s just that newer (in the sense of showing up in my library), more compelling work seduces me away from the “punishment reading” I’ve teeth-gritted myself into completing. Perhaps someday . . .

I cannot believe, however, that you never attempted Stranger in a Strange Land! (The extended-cut, unexpurgated version.) I just recently re-read that tome and found it as moving, dryly funny, subversive and wit-infused as ever. (Though there are a couple of jarring sexist comments in the text that didn’t age well.) You’ve got to give this book a chance, John! Give yourself a chance to “grok” it, water-brother! It’s Heinlein at peak Heinlein.

And that mind-blowing short story All You Zombies (originally written for—and rejected—by Playboy magazine). Absolutely brilliant! A time-travel story whose real impact only strikes once you’ve finished the tale and reflected on the meaning of the title.

Carl — we should start a club for people who gave up less than halfway through THE MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS…

I’m glad you mentioned STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND, because I totally forgot about it. I read it a few years after I gave up on FRIDAY, at the urging of friends, and did manage to finish it. Perhaps it was just oversold by all those friends telling me how great it was, but it didn’t really have an impact on me.

I don’t think of it as a novel, but to give Heinlein credit I should mention ORPHANS OF THE SKY, which I loved back then and still enjoy today:

https://www.blackgate.com/2021/02/21/vintage-treasures-orphans-of-the-sky-by-robert-a-heinlein/

LOL! Re: starting a “club for people who gave up less than halfway through THE MOON IS A HARSH MISTRESS”.

I checked out the link you provided to ORPHANS OF THE SKY. Haven’t read that “generations ship” novel. Sounds promising!

Different strokes for different folks – I loved The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. It’s a grown-up Red Planet, and I think it’s by far the best of Heinlein’s late novels, certainly more coherent and less self-indulgent than the windy, solipsistic, unreadable treatises that followed it.

I’ve thought for years that I need to reread Stranger in a Strange Land. I read it when I was twelve or so (obviously my parents let me read any damn thing I wanted) and that was waaay to early to pick up a lot of what was going on. I have the “unexpurgated” version around somewhere. Maybe next…

Carl mentioned the “unexpurgated” version of STRANGER IN A STRANGE LAND above…. is it substantially different from the original version?

John,

From a 1990 NY Times review of the text (they say it best):

The book had a long, uncertain evolution. There were many drafts. The final version, 220,000 words long (down from the 600,000 he had once envisioned), was finished in two feverish months and submitted in 1960 to G. P. Putnam’s Sons. Putnam accepted the book but requested that it be trimmed. Heinlein reluctantly complied, deleting 60,000 words and, in the process, some of the more provocative passages lampooning American attitudes toward sex and religion.

Even in its pared-down form, the book was intensely controversial. Some reviews were descriptive rather than judgmental. Others shared the ire expressed by Orville Prescott in the pages of The New York Times. The reviewer described the novel as a “disastrous mishmash of science fiction, laborious humor, dreary social satire and cheap eroticism.”

Despite such responses the book sold well. It quickly went into a book club edition, appeared in paperback, and eventually became the first science-fiction title to appear on The New York Times Book Review’s best-seller list. In 1989 Virginia Heinlein approached Putnam with the suggestion that the complete work, based on Heinlein’s working manuscript, should be published. While the restored version does not present a radically new work, it does offer readers a chance to watch Heinlein working out his ideas at greater length, and challenging society’s “sacred cows” with unexpurgated zest.

Heinlein was bemused by those who claimed that the work provided a blueprint for a new society. The novel was not written, he explained to one fan, to promulgate any set of beliefs. “I was not giving answers. I was trying to shake the reader loose from some preconceptions and induce him to think for himself, along new and fresh lines. In consequence, each reader gets something different out of that book because he himself supplies the answers . . . . It is an invitation to think — not to believe.” — RICHARD E. NICHOLLS

I bought this in hardcover when published, though I had some of the contents already. I was an Astounding reader from 1953 or so, and read Doot Into Summer, Double Star and other works there as well as buying Puppet Masters, Starship Troopers and others in paperback. I stopped reading his work after Stranger In A Strange Land, because he got way too wordy, off-kilter and odd. But this book! I hope he won’t be forgotten, he was a giant.

I envy you reading ASTOUNDING in the 50s, when it was regularly publishing Heinlein, Simak, Poul Anderson, Jack Vance, Murray Leinster, C. M. Kornbluth, Eric Frank Russell, James Blish, Walter M. Miller, Jr., Henry Kuttner, CL Moore, Theodore Sturgeon, and so many others.

I very much agree with Thomas, when he says above:

“Read a generous selection of the stories that were being published at the same time those early Heinlein stories were, and you’ll see why Heinlein’s made such an impact.”

Reading Heinlein in context, side by side with the other fiction in ASTOUNDING, is the right way to appreciate what he accomplished.

I did the next bext thing; I’ve read SF magazines chronologically, having now covered 1926-1960, but not reading eveything (I’m not totally crazy).

I’d say Heinlein was in a class of his own in the early 1940s. I think his payment from Astounding was also in a class of its own at the time.

After Pearl Harbour Kuttner&Moore aka Lewis Padgett was IMO top dog among SF writers a couple of years.

Simak also had a very strong period when he wrote the first City stories in the 1940s.

I must admit I also liked Van Vogt; his stories had that illusive “Sense of Wonder”.

And of course there was also Asimov (with much help from Campbell) with Nightfall and Foundation.

Lester del Rey and Sprague de Camp also had their best periods around 1940 IMO, and were frequent contributors.

Kornbluth only had one story IIRC (The Little Black Bag).

The early 1940 was a Golden Age in many ways. I think the quality to quantity was probably higher than during the SF boom in the 1950s.

Just to put Mr. Heinlein into some form of context, here we are discussing one collection of his major sf story arcs (the Future History saga), and it completely omits his seminal works on generation ships (“Universe”/”Common Sense”, later fixed up as Orphans of the Sky), or military-focused speculation (Starship Troopers, or time travel (“–All You Zombies”, “By His Bootstraps”), or augmented prosthetics (“Waldo”), or alternative (a-hem) lifestyles. Not to mention 4-dimensional objects like tesseracts (“And He Built a Crooked House”).

That being said, I too was an Asimov fan-boy in my younger years, with a best friend who went full RAH-RAH-RAH, which led to me reading more Heinlein than humans should be allowed to have. Still, for a few of his works, I have no regrets, like The Moon is a Harsh Mistress. And, not too many years ago, there was fun to be had at sf conventions by asking, during dull moments, “So, what as the last, GOOD Heinlein?”. Then, duck and cover!

As a teenager I devoured every Heinlein story and book I could get my hands on. Now as an old man I can’t stand them – the fascist politics, the preaching, the obvious manipulation of the story to prove a point. Even the subtle and not-so-subtle misogyny is abhorrent. It’s tempting to excuse him as a product of his time, but even that falls flat. The honorific “dean of American science fiction” is an insult to the genre.

My first experience with Heinlein was “Universe”, which totally blew my away like few other SF stories have done. I think I then tried to read “The Number of the Beast” and failed miserable. Obviously I had no idea of how different the older Heinlein would be compared to the younger one.

In more recent years I’ve enjoyed nearly all his stories up until “All You Zombies”.

Reading chronologically I think “Stranger in a Strange Land” is next on the list.

I like Heinlein’s stories. He was one of the most versatile writers of his generation, and also one of the more prescient ones I think. At least he seems to have made more of an effort on figuring out how future tech would affect societey. But his characters tend to all be the same Competent Man, and the main woman characters based on his wife, which I think was his main weakness in the first half of his career, along with the tendency to preach.

I regret not reading any of his juveniles as a kid. But I don’t recall ever seeing any of his (or Andre Norton’s) juveniles in translated form. I’m sure I would have liked them!