Amazing Stories, November 1989: A Retro Review

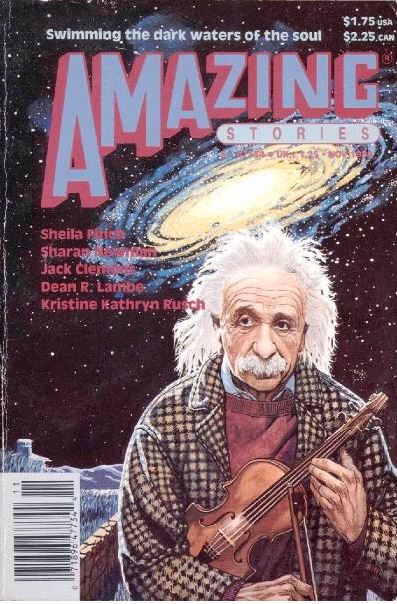

Amazing Stories, November 1989. Cover by Janet Aulisio

An unexpected issue came up during my reading of the November, 1989 Amazing Stories. In 1979 I was 10 years old, and I barely remember being 10 years old. In 1989 I was 20, and I remember being 20; maybe not 100%, but I remember enough. In fact, I remember enough to know what 20-year-old me (20YOM) would think of the stories in the November, 1989 cadre. Sometimes, 20YOM’s views conflicts with 51-year-old-me (51YOM). So there are times I am literally of two minds!

On to it!

Reflect-

Hold the clunky 80s cordless phone! What is this ad on the first page? GammaRauders: Revenge of the Factoids! How did this escape my notice back in the day? GammaRauders was is one of my favorite games. Pacratula forever! 20YOM would have balked at the cost, but 51YOM laughs at the cost from my mountain of financial power.

Reflections, Editorial, by Robert Silverberg. Silverberg again! He has his ink-stained fingers in many sinister soups! He has concerns about the mountain of trash at New York City Fresh Kills Landfill.

If New York City can generate enough garbage between now and the year 2005 (not so far away!) to build a pyramid out of it bigger than Khufu’s, where are they going to put the garbage they produce between 2005 and 2025, […]? Do they envisage an ever-growing plantation of pyramids spreading across all of Stanton Island?.

20YOM would have been very interested in this editorial, being in the second year of my chemistry degree at Central State University* in preparation for my Environmental Science degree at the University of Oklahoma. Unfortunately for you, dear reader, I not only got the degree, but I know the complex language of landfills like Elrond knows Moon Runes.

But I save the tales for the fiction, so I’ll hit you with some ferocious facts! Before RCRA subtitle C was passed in 1976, nonhazardous and hazardous waste were mixed willy-nilly and thrown into any convenient gully or hole, so every landfill pre-1976 is like a donut of well-regulated waste segregation surrounding a core of nonhazardous/hazardous waste.

The Fresh Kills Landfill was successfully closed by The Man in 2001. Or as successfully as such a thing can be. Groundwater quality and landfill gas (because landfills generate their own explosive gasses) are both monitored and controlled. In fact, the landfill gasses are collected purified and are part of a fairly successful waste-to-energy system.

Its 2021, are we living in the future? Are we handling our waste our any better than we were ‘89? Well, yes and no. As far as hazardous waste goes we’ve put together an infrastructure to deal with it, and many products and materials have either no or reduced hazardous constituents. Regarding the volume of nonhazardous waste? NO!

NYC is now hauling its waste further out of state and thus pumping more greenhouse gasses into the atmosphere. Can’t we burn trash directly for energy recovery? Sure, but have you ever seen municipal solid waste? The plastics, the batteries, the household chemicals—so controlling air emissions? Expensive. And Easily jacked up.

Enough of that, though. We’ve got fiction to focus on.

Fiction, “The Old Man and C,” by Sheila Finch, artwork by Janet Aulisio.

Okay, this is a story about Albert Einstein, it tips is old-school Holmberg to Ernest Hemmingway’s “the Old Man in the Sea” and the scientific abbreviation for the speed of light (‘c’). It’s kind of an alternate history, with Einstein teaching violin lessons, his students scoring big in the local competitions, but he finds himself distracted, mesmerized by light.

Yes, the war. The strangeness of the place-names, Seoul, Pyongyang, Pusan. And the stupidity of young boys killing other young boys in jungles and rice paddies where light slanted through palm trees and bamboo thickets, light that had crossed the darkness of space from a distant star to illuminate a scene for painters.

[Albert Einstein asked] “They’re still fighting?”

“Papa!” Then another idea seemed to occur to his son. “Are you feeling well.?”

“You’re going to tell me that the American airplanes dropped a most peculiar bomb on a Korean town with a name as singular as roses. Isn’t this so?”

“Yes — but, roses? Anyway, let me tell you about this weapon, Papa! A great advance — the future beckoning! — You see what they’ve proved? A particle of matter can be converted into enormous outburst of energy. This is something we’ve been working on here at the university, splitting uranium atoms.”

“Light,” he said. “It travels so fast! No time at all, really, from our point of view.”

Hans Albert was silent. After a while he said casually, “Is Mama there? Let me speak to her.”

Fiction, “The Importance of the Buffalo,” by Forest Arthur Ormes, art by Janet Aulsio.

Academia is a special kind of hell, and the future of this story is remarkably unkind to teachers. Gertrude Rasport has traveled to see her separated husband, Bernard, following up on his employment leads. Of course, both Gertrude and Bernard used to be teachers, and teachers are particularly loathed in the future.

This story has almost uncanny resonance. First, a lot of teachers are pretty full of themselves. Second, The Man hates it when teachers stick up for themselves—in the world of this story they are condemned to menial jobs by the Elderly Work Programs Administration (EWPA), and in the real world, the big teacher’s strikes during 2018 in Oklahoma, West Virginia, Arizona, Kentucky, North Carolina, and Colorado has created ferocious, even life-threatening backlash. In Oklahoma as soon as coronavirus was shown to be lethal, the conservative government here ensured that schools would stay open. Horrible.

But then, teachers can be a fairly prickly bunch, as is Gertrude Rasport. Bernard has asked his separated wife to meet him, he’s got good news: he has been offered a job in a museum playing piano. You know, how people used to play pianos before machines. He is hoping that she’d like to go with him. But Gertrude Rasport is a teacher’s teacher, and by that I mean it isn’t enough that her students are willing to learn the names and dates, or even that they want to learn them, but they have to have a passion for the subject that transcends the names and dates. You know, a passion like hers.

Thus she’s skipping out on the EWPA, getting in trouble with the Man and risking Bernard’s future career because she is hung up on the whole teaching thing.

How hung up? Cult-level hung up. Gertrude’s plan is to join a cult. Or a cult-like place–some place in Colorado where parents send their kids to the teaching machine centers during the day but have human teachers teach them at night. I can’t help but notice she doesn’t talk about how the kids might feel about that.

The more I think about the story the more I think that Gertrude is a very much an intentionally dislikable character, but there are great moments between her and Bernard. They are trying to reconnect, and it just isn’t working. Bernard has a good thing, a good gig that lets him play piano—and although The Man doesn’t need piano teachers, there are plenty of dingy dives that do. Bernard’s stopped teaching piano and began playing—something that Gertrude just can’t, or won’t, do.

Bernard is caring, understanding, but unwilling to endanger the good deal he’s got.

There are several things that the story does well—mostly by focusing on a future where a lot of people are out of work because of machines: self-driving cabs, and automated monorails for example, which in turn affect how social security gets funded, which pushed back retirement dates, and leads to the creation of make-work programs like the EWPA. Also remarkable is how quickly it happens, how fast the roll-out of the teaching machines was, and how fast the self-driving cabs put regular cab drivers out of work. I myself remember how quickly Bird scooters took over every major city in America.

I’m not sure if the point of the story is that we need to understand the past, or if it is just that teachers are arrogant self-centered pricks. Or maybe it is that the sad irony of a history teacher not realizing that she needs to keep up with the times. Or maybe I just find the artwork very offputting.

Article, The Sin of Yin, the Clang of Yang, by Dean R. Lambe

Dean Lambe rails against the non-othering of the other and that modern Sci-fi doesn’t have enough othering. He seems to be losing the current war by fighting the last war, which in SF in 1989 seems to be the New Wave and all those ‘soft’ SF stories and writers. Or something.

It’s as if the medium has been eaten by a dystopian message; as if the cold, dark side of the hill, the yin of negativizes, has overcome the classic, strong, positive, and bright yang of SF. Have writers who were 1960s Flow Children gone to seed? Do their works have “special agendas” of environmentalist atonement, of catharsis, through surrender to the engulfing alien Other, where the mystic (and mythic) East is always somehow better than Yankee know-how, than R&D for you and me?”

[…]In the “Tao of biology” of many prominent writers, only yin succeeds and the yang of science and progress not only fails but is the devil’s work. All too often, a “limits of growth scenario is coupled with an environmentalist retreat to the simple life,” with no thought to how brutal and short said simplicity would be when the microchips fail.

I’ve never said this before, and I may never again, but my overall take on this was “Okay, Boomer.”

Lambe has a real ‘space or bust’ vibe, as well, and like so many of the ‘space or bust’ guys (almost always guys), he’s got a real issue with all these non-space sci-fi stories.

Of course, a lot of the essay seems to be laying down the groundwork for his recent novel The Odysseus Solution where humanity throws off the chains of (supposedly) virtuous alien overlords.

Poem, Nuclear Spring, by Darrel Schweitzer, art by Janet Aulisio.

I don’t usually review poetry, but I’ve been running across Schweitzer from the start of this project– mostly through his letters, so I had to give this some attention. Also, given that this poem comes right on the heels of Lambe’s essay, I think that editor Patrick Lucien Price was pushing back a little!

Schweitzer’s poem focuses on the animals, jubilant to be in post-nuclear war hellscape, a world free of mankind, until the rat brings word that there are still humans around, grubbing (badly) for worms.

Then rose the great whale

out of the blackened deep,

dying, the last of his kind,

his island back volcanic with sores.

“let Mankind sing my song,

that it may continue after I’m gone.

The rest of you, go on speaking.

Hide nothing.

Join voices with his in our peaceable kingdom,

without any master,

without any judge,

for Man is a beast now,

merely one of the us at last.”

Are the animals mutants and able to speak or are the humans mutants and dumb? There is a delectable lack of clarity in the poem.

Fiction, “Woody & Me,” by Sharan Newman, art by Paul Jaquays

The ‘me’ of the story is a simple country girl, and “Woody” is her man. But Woody is also something else, whether a renegade angel or some kind of fae creature is never made clear. But Woody is a dreamer and when the couple goes to a traveling circus, they run into more dreamers, or demons, or whatever they are. ‘Me’ is pretty dense, so the conversations go straight over her head. I got the feeling that Newman was referencing something, some great work of literature, that I haven’t read and thus most of it went right over my head, too.

I will say that Newman doesn’t understand country folk. Newman wrote a lot of Arthurian (or perhaps Geunevierian) historical fiction/fantasy, so maybe the story was about that. She wrote short stories sporadically from the late 80s to the about 2010.

Poem, Dorothy and the Sequels, by Ruth Berman

A short poem about how, in spite of all the sequels to the Wizard of Oz, Dorothy never is the protagonist of one of them. Having not read those sequels, I can’t say for sure if this is accurate or not.

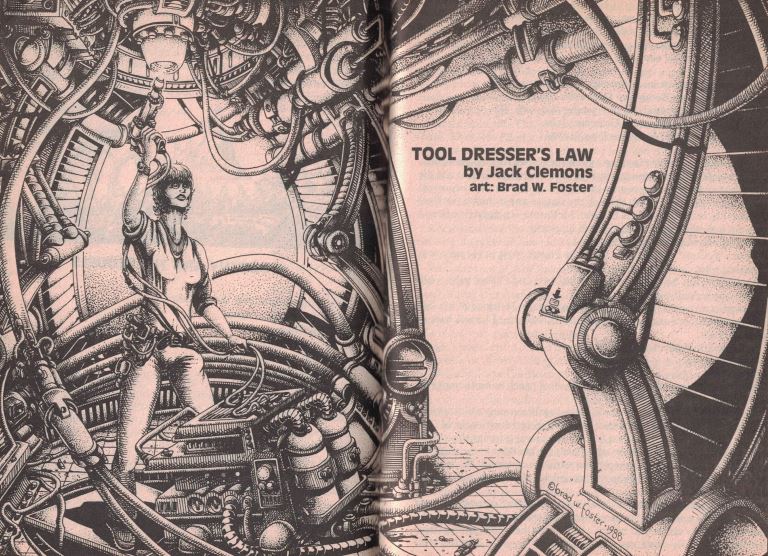

Fiction, “Tool Dresser’s Law,” by Jack Clemons, art by Brad Foster

Clarence Mowboata is a surveyor on the spaceship Wildcatter in this near-future swingin’-dick space mining adventure. Wildcatter is pushed to its limits by its owner, Old Man Snyder, to catch up to a roaming space-rock called Hawking. Hawking is an anomaly and a mystery, it is believed that it is a Hawking Quantum Black hole at its center, but that doesn’t explain why it has a crust, why it has a surface at all. Thus there are potential riches (at least scientific ones) to be found.

Like so many of these swingin’-dick space mining adventure stories, there is a lot of information on the financial shares of each crewmember and how Old Man Snyder uses it to get ‘em all by the short and curlies.

After a near-disaster landing, they set up a temporary atmosphere tent between the ship and the surface of Hawking and they start drilling their well/core. Now, the Tool Dresser in question is the young Pat Talbot. Back in the day a tool dresser was a person who re-sharpened the drill bit on a well, future tool dressers re-calibrate the laser dingus.

It takes a bit of time to get to the real issue of the story, which is that:

The dressing-tool cart was balanced on its rear wheels at the edge of the four-foot-diameter drill hole. The rest of the cart was suspended over the hole, the front wheels dangling over a thousand feet of nothing. Pat had managed to partially cover the opposite edge of the hole with a slab of heavy metal — it looked like a short section of shield wall material — and the provided just enough of a ledge to support the front lip of the cart. Pat stood on the slab like a shapely Atlas, legs spread wide, straddling the hoses and lines, and was lasing the nozzle tip suspended directly over her head.

Cal came sliding down right behind me, and when he saw what she was doing , he was immediately pissed. He shouted at her in that booming voice he had developed form years of working around noise. I saw her jerk her head down to look at him, and then she lost her balance. Instinctively, she kicked off the slab to keep from falling into the hole. The slab shifted, the cart tumbled, and Wildcatter lost an essential, and irreplaceable, tool down a 300-meter throat of rock.

A good portion of the rest of the story is them trying to get the cart and the laser tool back up out of the hole. They spend days at it, and Clemons actually handles the boredom and stress of the characters over days without boring the reader. The cart and the metal slab are lodged on the side of the hole and they finally just charge up the laser and it ends up cutting enough of the slab for them to finally pull it up.

There is one problem with all this, though. All the swingin’ dick talk and they never lower somebody down the hole — they never even talk about it as an option to turn it down because of safety reasons or whatnot. It’s an oddly specific omission.

Old Man Synder balls Pat the hell out, firing her so she gets none of the shares she signed up for and may in fact be in the red for food and board and the trip back. In retaliation she releases the magnetic clamp that is holding the dresser tool over the hole and dumps it all back down. The rest of the crew essentially quits at that point, and then they are fired. They stow and ship off.

For all the fascination with Hawking, they don’t find anything worth the trip and about an hour after they leave the realize that Pat has skipped out on them and remained on the planet. Which is ballsy, but then it turns out she got rescued by an Israeli scientific probe, which seemed like a real stretch. If there were hints of some kind of international space-intrigue (and thus maybe she botched up the job on purpose being some kind of international space-spy), but honestly if there was it went right over my head.

Clemons was a NASA engineer, one of the top dogs. That explains the detail and the gritty reality of the story, but it doesn’t explain why he, and just about everyone else who writes these mining stories that make space, working in space, the people working in space, and everything about it appear to be as unappealing as possible.

Fiction, “Fugue” by Kristine Kathryn Rush, arty by Hank Jankus

Stories from the killer’s POV are always hard sells. Well, the POV switches between the Killer, Mr. Bassinger, an old man living alone in a dicey part of town, Sara, a medical home health worker who works with Mr. Bassinger, Ricky, the deranged killer whose murders are all delusions of art, and Jaaene, a two-dimensional shadow being who has been exiled to Earth and is possessing Ricky.

The story is overly convoluted and there is a lot of set-up for not a whole lot of payoff.

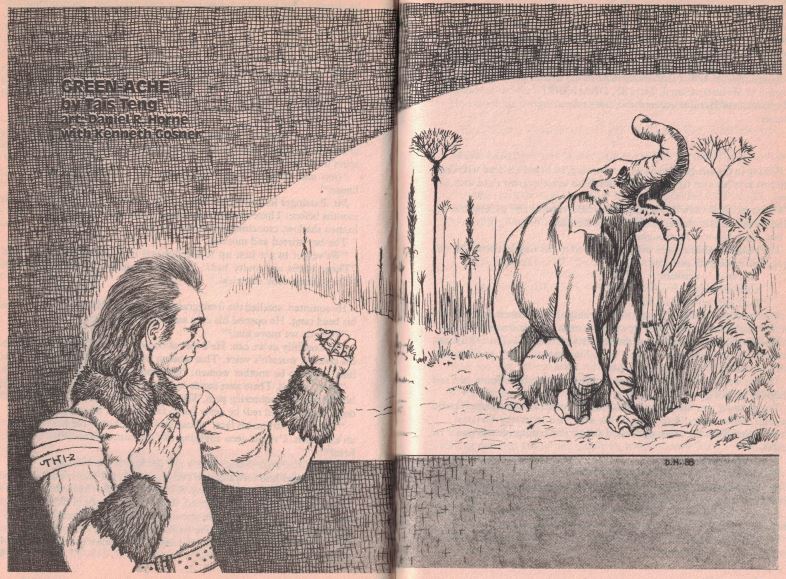

Fiction, “Green Ache” by Tais Teng, Art by Daniel Horne and Kenneth Gosner.

Okay, this story is way too convoluted. A dead wife who’s V R recording is interactive and still activated, the Green Ache, the Government, the Ymnd with their Time Machines and within them The Game. This is one of the most frustrating kinds of stories: one that has a lot of interesting ideas, but also is much weaker than the sum of its parts.

Behind the portal the Yemndi home-time stretched: an Earth so incredibly aged that all ther isotopes had turned into stable elements. The oceans were long since gone, leaving the dust, the airless deserts. A white dwarf, never rising or setting, illuminated the desolate landscape. […] All useful power sources gone, their sun in its dotage, the guardian computer network of the Yemendi had sent them back int the past. High tech-civilization dotted Earth’s long time stream, only some of it human.

Sounds cool, but it isn’t, really. The Yemndi do this weird thing where they charge (in precious metals or unstable isotopes) for time in their time machine, but somehow the time machine’s are hooked to the user’s consciousness and you have to go through all the epochs of earth’s history, starting from just after the planets formation. For points or something, as long as you can last.

Honestly, I gave up on this one.

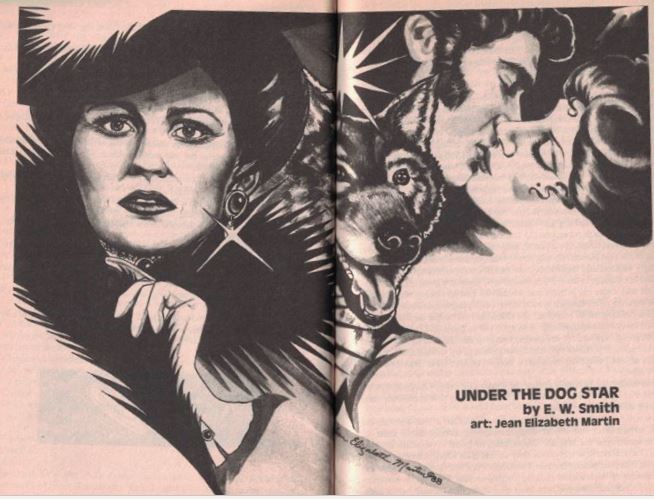

Fiction, “Under the Dog Star,” by E.W. Smith, art by Jean Elizabeth Martin.

Clocking in at 51 pages, this is by far the largest story in the magazine, and while it’s well written, it’s just not that great. Margaret Essenden is a spirited hard-hitting female journalist in Edwardian England, travelling the world and writing articles. She’s hitting middle age and some of the mistakes of her spirited youth are coming back to haunt her in the form of Grey, her illegitimate child she left with his father. His father recently died and now Grey, a fuming angry young man of 20 is killing time with his mom as they try to get to know each other.

Most of the story takes place in the north of England, at the stately estate of one Lord Grogon, a man of the world and of the sciences, and one-time lover of Margaret Essenden, most of the action centers around two odd guests of Grogon, a brother and sister named Proctor and Serena De Canis, a twee pair with a mysterious past and somewhat odd behavior. Long rambling early 20th century conversations ensure, that often seem to center on dogs. It is the dog days of summer, they can see Sirius the dog star. There are discussions of Greek mythic dogs, Hungarian werewolf myths, Celtic mythic hounds, and the hound of the Baskervilles. Proctor de Canis is obviously a lycanthrope, or a dog alien, or something.

He makes the mistake of raiding the same chicken coup twice and Grey, looking to be big hero and all that, blasts him with a shotgun. Or blasts him by accident trying to shoot a mad dog. That really puts the skids on his already troubled attempts to get close to quaking violet Serena.

The party ends at Lord Gorgon’s, and while everybody else may want to mope around and lick their emotional wounds, Margaret Essenden’s got articles to write and a steamer to catch and Grey travels with her. The estranged mother and son bond a bit, there is a horse riding accident, and some potential Hungarian werewolf action, and Grey, who was developing some article writing skills of his own, is shot dead investigating some Hungarian rebel action.

Margaret Essenden is all-but beat-down by the tragic events of the year, and the story ends with an oddly hopeful note when one of Lord Grogon’s other guests makes contact with her with an update about the people and events from the summer.

[Dr.] Markham wrote to tell me that Serena had died in childbirth, leaving behind a son and a daughter, twins, who were weak from their early struggle into this world but were likely to live. Henry [Grogon] he wrote, was devastated.

I should have accorded Dr. Markham more credit, for he was a good man and not such a fool as his search for woman’s acclaim made him seem. His letter was clever in what it left unsaid. Nowhere did he say, “Go to Lord Grogan.” Nowhere did he say, “It is for you own good as much as his.” Nowhere did he say, “There are two dear children in need of care.”

This was one of those stories that was well written, but slow and whose cardboard characters E.W. Smith turned remarkably deep with envious ease. Still, not just a whole lot happened, and the mystery of the De Canis twins was never revealed, although Margaret, going to help raise the children with her ex-lover might also be planning on investing it further. One of those stories that I kept reading because I’d already invested so much into it.

E.W. Smith seems to have not written much else.

Poem “in Re: Digital” by W. Gregory Stewart

The issue ends with a late 80s warning shot about computers — oh Stewart, we should have listened!

I do not trust the digital packaging of truth;

I have analog eyes and analog ears and I want

analog reality, not

stop-motion/clay-mation/gumbyland views of

the wat it mostly seems to be.

in a land of the digital metriphiliacs I

am an analog-retentive

Inflections, letters section

Editors Patrick Lucien Price is taken to task for publishing editorials lambasting Christian attempts to force their creation myths in schools and publishing stories about inter-species-AI-erotica. There was also a throwback to 1969’s “Amazing” letters column, with letter-writer James T. Sizemore wanting Science-Fiction to address The Problems.

Right here in “the good old USA,” millions are homeless or starving. Pollution (land, sea, and air) is a significant problem, and there are many others. There is no shortage of ideas.

20YOM would have had similar feelings, and 51YOM still has similar feelings.

*CSU no longer exists, as such. It was renamed to University of Central Oklahoma in like 2008. That didn’t make me feel old.

Previous entries the Quatro-Decadal Reviews include:

November 1969

Amazing Stories

Galaxy Science Fiction,

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction

Worlds of If

Analog Science Fiction/Science Fact

Venture Science Fiction

A Decadal Review of Science Fiction from November 1969: Wrap-up

November 1979

Quatro-Decadal Review, November 1979: A Brief Look Back

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction

Galileo Magazine of Science & Fiction

Analog Science Fiction Science Fact

Isaac Asimov’s Science Fiction

Amazing Stories

Omni

A Decadal Review of Science Fiction from 1979: Wrap-up

November 1989

Jump Back! Quatro-Decadal Review, Looking Ahead to November, 1989

Adrian Simmons is an editor for Heroic Fantasy Quarterly, check out their Best-of Volume 3 Anthology, or support them on Patreon!