Rod Serling’s Night Gallery: The Art of Darkness

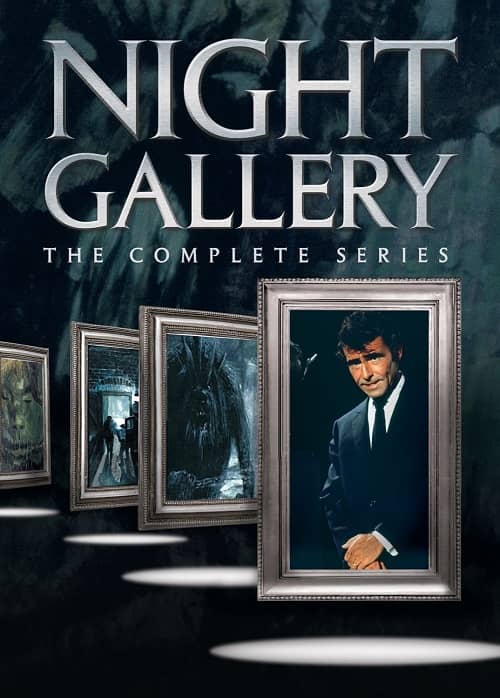

The Night Gallery on DVD

Few things in life are more trying than playing second fiddle to a sibling whose charm, poise, good looks and dazzling achievements you can never hope to match. Just ask Night Gallery, forever standing in the shadow of one of the most legendary and beloved of all television shows, The Twilight Zone. (At this point I am morally – if not legally – required to disclose that I am a spoiled youngest child who got every freakin’ thing he ever wanted, at least according to my sister.)

In case you need reminding, Night Gallery was an outré-story anthology show hosted by Rod Serling that ran for three seasons on NBC, from 1969 through 1973. Each hour-long episode featured two, three, or even four separate stories (at least until the third season, when the show’s running time was cut back to a half hour), which Serling, in his role as the curator of a museum of the macabre, would introduce with a painting (or occasionally a piece of sculpture) illustrative of the tale, hence the series name.

Night Gallery shares many qualities with its predecessor, but several things distinguish it from the earlier show. Like Twilight Zone, Night Gallery was created by Rod Serling and he wrote some or all of over half of the episodes, but he did not produce the series. This was a big change and it meant that he had far less authority over Night Gallery than he did over his previous creation. (As the creator and face of the show, he thought that his wishes would be respected even without the producing title, but it often didn’t turn out that way.)

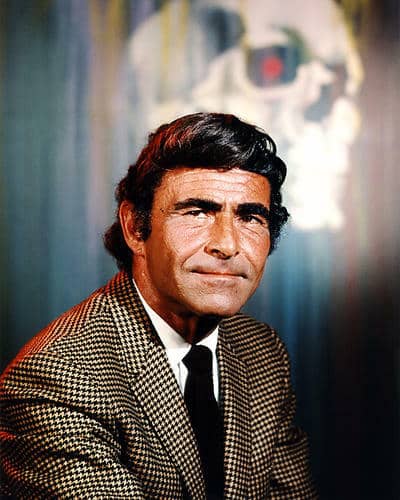

Rod Serling

During the course of the show’s run, budgets and ratings declined together, and Serling and his producer Jack Laird came under pressure to spice the program up with more action and violence; at one point Serling complained that the network wanted to turn Night Gallery into “Mannix with a shroud.” (For those yet to receive their AARP cards, Mannix was a very popular detective series stuffed to overflowing with fistfights, car chases and gunplay; Mike Connors’ Joe Mannix suffered more bullet wounds than your average in-country infantry battalion and was pistol whipped into unconsciousness an average of seventeen times a season for the eight years the show ran. I know this because I counted.)

During its five seasons (1959 to 1964), The Twilight Zone featured a full mix of science fiction, fantasy, and horror, but Night Gallery’s emphasis was overwhelmingly on horror, and many episodes were adapted from stories by the genre’s biggest names, including H.P. Lovecraft, Clark Ashton Smith, Algernon Blackwood, Robert Bloch, Fritz Leiber, and Richard Matheson, to name only a few.

Anthology shows tend to be uneven and Night Gallery was not exempt, the downside frequently being found in Serling’s own original contributions, which often feature the soppy sentimentality and weepy self-pity that were his specialties. Entries like “The Messiah on Mott Street” (a tenement-dwelling little boy needs a miracle to save his dying grandfather – played by the great Edward G. Robinson – and surprise, surprise, at the last possible moment he gets one) and “They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar” (a suicidal business failure encounters the ghosts of his past in the deserted saloon where he spent the happy days of his long-departed youth and comes away having – you guessed it – learned a valuable life lesson) show Serling at his diagrammatic worst. They might have slipped by in the 70’s (“Tim Riley” was even nominated for an Emmy) but they can be pretty hard to take now.

Welcome to the Night Gallery

Spotty quality may have shortened the show’s run, but what hurts most watching the series now is its bland look, which isn’t anyone’s fault really; that’s just how television was in those days. It wasn’t always so; most of Twilight Zone’s black and white episodes still have a certain visual elegance. They look good whether the stories themselves are strong or weak. By the 70’s, though, black and white was a thing of the past and television shows tended to feature Brady Bunch-esque color palettes and oscillated between looking merely dull and flat-out dreadful, with people wearing godawful clothes (the decade was the millennium’s sartorial low point – remember Lee Majors’ aircraft carrier-sized collars on The Six Million Dollar Man?) walking around tacky, flatly-lit sets. Because of their generally dark tone, Night Gallery episodes usually manage to avoid the worst of these pitfalls, but even so the series generated few really striking visuals. Even Serling appears haggard and frayed at the edges, in contrast to his sharp look on his earlier series; clearly decades of fighting the suits had taken a heavy toll.

The lack of visual distinction on Night Gallery makes a big difference. Quick – think of memorable Twilight Zone images. Easy, isn’t it? From Jean Marsh’s bullet-shattered android face in “The Lonely” to the fascist noir courtroom in “The Obsolete Man” to the pig faced aliens in “Eye of the Beholder,” the series abounds in sights that once seen are never forgotten. On the other hand, it’s hard to think of a single elegant or memorable visual from Night Gallery. When the episodes are good it’s almost completely a function of writing and acting – not a bad thing, certainly, but it does tend to limit the show’s hold on the memory. Everyone on earth has a favorite Twilight Zone episode; if you penetrated the deepest jungles of Borneo and spoke to the chief of the most isolated tribe, you would probably discover that he just loves “that one where Burgess Meredith breaks his glasses.” Night Gallery, on the other hand, hampered by a look as exciting as a speech by a school board candidate and lacking the endless syndication afterlife of The Twilight Zone, lives on only for a dwindling cohort, greying refugees from the Gerald Ford administration.

Rod Serling with Witches’ Feast painting

So why bother to remember it at all? Because, despite its handicaps, Night Gallery often managed to be quite good. Standout segments include a pair of fine Lovecraft adaptations, “Cool Air” and Pickman’s Model,” an Orson Welles-narrated telling of Conrad Aiken’s haunting story of a child’s descent into schizophrenia, “Silent Snow, Secret Snow,” and an excellent version of C.M. Kornbluth’s science fiction classic, “The Little Black Bag” starring that Twilight Zone alumnus, Burgess Meredith.

Two of the best Serling originals are “Class of 99,” which chillingly features Vincent Price as a college professor instructing a class of androids in the finer points of emulating their now-extinct creators – that is, in how to lie, cheat, exploit, humiliate and kill for their own advantage, just like any full-fledged human being, while “The Waiting Room” serves up a satisfying dose of existential weirdness, as Old West gunfighters sit around a dingy saloon until the clock on the wall tolls the hour of their death, when they must exit the bar to be hung or gunned down or otherwise meet their violent ends, only to then return to the saloon and do it all over again, for eternity. On the whole, for any lover of horror or dark fantasy, the show’s ratio of hits verses misses is good enough to make it well worth watching, even now.

And when I said that Night Gallery was a show with no visual distinction, I was not completely correct; while the episodes themselves were rarely memorable visually, the paintings that were featured in Serling’s introductions to each segment often were, a point which I am now in a position to appreciate better than ever.

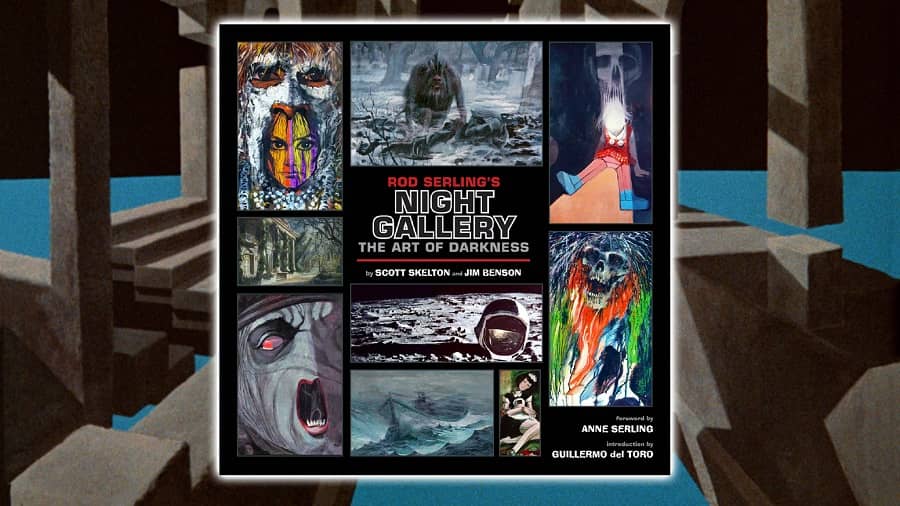

Rod Serling’s Night Gallery: The Art of Darkness

There’s an old saying: be careful what you wish for – you may get it. I didn’t even know I was wishing for anything when, a few months ago, I sat down to watch a Night Gallery episode (all three seasons are available on DVD, which is the best way to see them – the series was butchered in syndication). In the course of the hour, I remarked to my wife that I wondered what had become of the paintings that were done for the show. She took note of my interest, got together with my daughter, and lo and behold, a short time ago a surprise package arrived at my house, containing a belated Christmas gift – a large, heavy book entitled Rod Serling’s Night Gallery: The Art of Darkness.

Written by Scott Skelton with Jim Benson, the book is the result of a Kickstarter campaign but is still available for latecomers at creaturefeatures.com. It’s a beautifully produced, oversize hardcover volume of 304 pages with an introduction by Night Gallery fan Guillermo del Toro (who also did commentary on some episodes on the DVD’s). The book gives a history of the series, but best of all it reproduces in full-color every painting done for the show. Each painting has a full page for itself, facing another page that gives Serling’s introduction to the segment along with information about the painting and how it was created.

Jaroslav Gebr’s pilot episode painting, The Cemetery

The paintings for the pilot episode were done by Jaroslav Gebr, but he was not available for the series. That duty was given to Thomas J. Wright, an artist at Universal Studios, and he was responsible for all of the paintings which subsequently graced the show for the rest of its three-year run. According to the book,

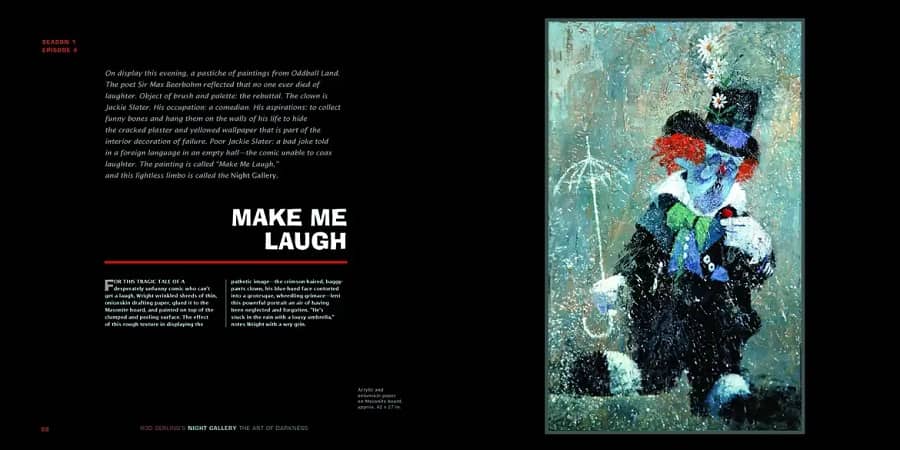

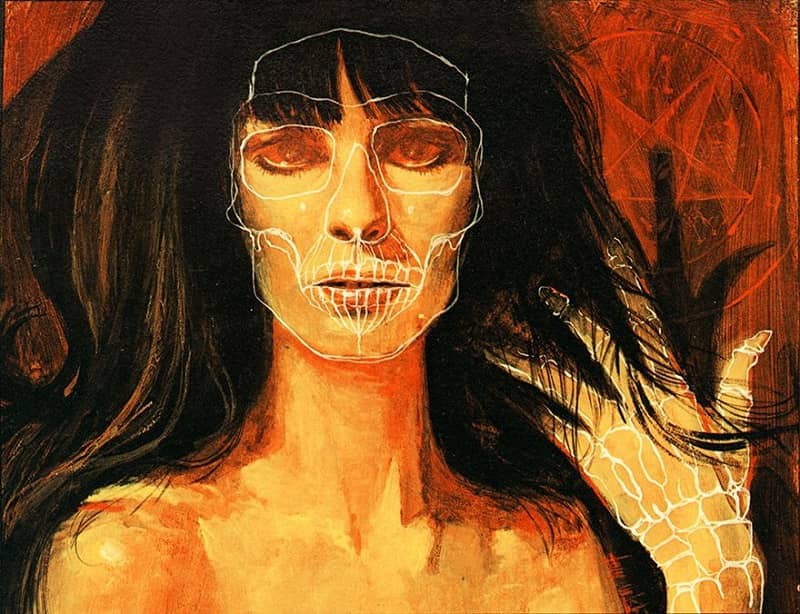

With the exception of ‘Pickman’s Model,’ the single script in which the painting was described, Wright was given free reign to interpret the stories in any way that sparked his imagination. Because of this freedom, his canvasses are highly varied in their subject matter, style, color palette, and inspiration in ways that Gebr’s cannot approach: still lifes and abstracts, expressionism, impressionism, modernism, romanticism, American realism, primitivism, surrealism, folk art, cartoons – whatever style struck his fancy and seemed appropriate in expressing the tone and themes of the stories.

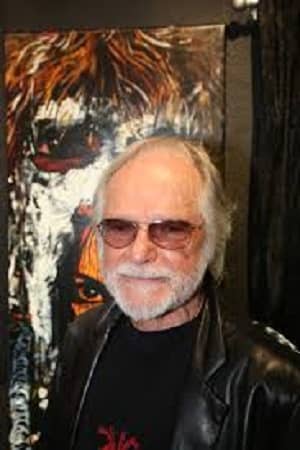

Thomas Wright

Wright was so successful in his task of shaping his work to the individual tales that until I read The Art of Darkness I never realized that the paintings were all the work of one man; I always assumed that they were the work of a team of artists, though seeing them all in one place as the book allows you to do makes Wright’s individual artistic fingerprint more evident. In any case, it’s a pleasure to be able to take a long, close look at this wonderful work, something that a fleeting glimpse on a television screen doesn’t permit. For anyone who loves Night Gallery or appreciates macabre or fantasy art in general, The Art of Darkness is a real treasure.

Make Me Laugh (spread from The Art of Darkness)

As for my original question – what happened to the paintings? “Most of the paintings were stripped from their frames and warehoused in the Universal property department” and from there they were used as set decorations for movies and television shows. (Some of them found their way into two Columbo episodes, for instance.)

Some of them even wound up decorating the offices of actors or producers at Universal. As late as ten years after the show’s cancellation, fifty of Wright’s paintings were still in the Universal property rooms, but in the decades since, that number has “dropped to a mere handful.”

Daughter of Darkness

The others have gradually made their way out into the wider world through various modes of misplacement and appropriation (Universal even sold some – in the early 90’s one lucky lady got two Night Gallery paintings for twenty-five dollars… plus a dollar sixty-nine tax), and many have ultimately come to rest in the hands of private collectors through auction houses and other means. Gallery exhibitions of the paintings have even been put together from time to time, usually in Los Angeles, naturally.

The Girl with the Hungry Eyes

If you want a close view of the work Wright did for the series, you can buy The Art of Darkness, you can wait for a new showing, or if you have eight or ten thousand dollars in your couch cushions, you might even be able to acquire one of the original paintings. (The early 90’s are long gone, needless to say.)

2019 Exhibition

Or you could go on eBay and pick up a copy done in Hong Kong. They look pretty good and one will only set you back two hundred dollars. Of course, in that sort of deal, you could get more than you bargained for… you may end up with a cursed canvas that inexorably draws viewers into a nightmarish world from which they can’t escape, and the next owner of the painting may notice a small, frightened figure that looks just like you in the background, frantically pleading to get out… hey! Sounds like a good Night Gallery story…

Thomas Parker is a native Southern Californian and a lifelong science fiction, fantasy, and mystery fan. When not corrupting the next generation as a fourth grade teacher, he collects Roger Corman movies, Silver Age comic books, Ace doubles, and despairing looks from his wife. His last article for us was a review of the films The Black Hole And Saturn 3.

Thomas, I remembered 2 episodes from “Night Gallery” which I saw when they were initially broadcast. In the first, “The Caterpillar,” Laurence Harvey’s character has an unfortunate run-in with some earwigs, and in the second, “Fright Night,” Stuart Whitman’s character gets an unexpected visit from a rather grim-looking Alan Napier, who’s shown up ro retrieve a trunk. A few years ago, I purchased the 3 DVDs you mention here, and not long after, on Halloween, showed “Fright Night” to some of the college students I’d taught, hoping they’d be as chilled by the episode as I’d been more than 40 years earlier. To my great disappointment, all of us watching were let down by what turned out to be rather mediocre at best. My memory had made that episode more frightful than it turned out to be, but I’d seen it the first time when I was the only one home, so perhaps that gave it more “fright-weight.” I haven’t watched any more of the DVDs since, but maybe I’ll give them another try in October. And thanks for the tip about the book collecting the paintings — I’ll have to see about picking up a copy of it. That those paintings may have been the best part of the series is a shame, but you’re spot-on with your assessment of Serling’s diminished talents.

Fair review of a very uneven series. (Gods spare us the “humor” injected by Jack Laird over Serling’s vociferous objections into the show!) You’ve pointed out a couple of very good episodes; Smitty59 has referenced the cringe-inducing body horror of “The Caterpillar”. I’d like to nominate “A Question of Fear/The Devil is Not Mocked” starring a black eye-patched Leslie Nielson as the merc colonel who accepts a $10,000 bet to spend a night alone in a haunted house. Someone, someday, should put out a “Best Of” Night Gallery DVD: the top 10 episodes.

I think it was just very hard for a 70’s show to be truly scary – everything worked against it, which is why shows that managed to be frightening (like the Night Stalker and Trilogy of Terror for the ABC Movie of the week) were such outliers. It was different in the 50’s and early 60’s – shows like The Twilight Zone, The Outer Limits, Alfred Hitchcock Presents, and Boris Karloff’s Chiller generated a lot of real scares. What was the difference? I think black and white helped, but I’m not sure if that’s the whole story. In any case, I think Carl’s suggestion about a “best of” selection from Night Gallery would serve the show well.

Whoops – that should have been Thriller, not Chiller. Forgive me, Boris!

I’ve only watched some of the episodes that were based on older short stories that I’ve read. Of these the most memorable one was “Brenda”, based on a 1954 story by Margaret St. Clair. The TV show actually managed to improve the ending of the rather off beat story.

I remember that one, Knut – I’ve never read the story, but it was one of the more effective episodes.

My wife and I caught several of these on ME TV a couple of years ago–I think they showed them after they ran out of original Twilight Zones. Anyway, as a kid, NIGHT GALLERY scared the bejeezus out of me! Even reruns in the 80s gave me the creeps. This time around… meh. We didn’t see them all, but most of them were mediocre. There were a few good episodes, but nothing really scary.

I say that with one exception– there was one about a criminal on the run who is hiding out in a funeral home and is taken in by the funeral home director, who is a very lonely and sad man. He’s also a man who has, through the years, very selectively, robbed graves to create a ‘family’ for himself in a secret room of the funeral home. The funeral home director wants to take the criminal in as an apprentice, and he can be the ‘long lost cousin’ character in the family. It was completely unnerving because the funeral director wasn’t going to murder the criminal or anything, it was that he was so crazy, so far gone, that he could deliver this request completely honest and straight.

Two episodes seared into my memory is the series of paintings nefariously commissioned to frighten a wealthy owner to death in his mansion, the paintings being of a corpse gradually making its way to the door of his mansion. . . . the paintings however backfire on the perpetrator of this crime of greed for an inheritance.

The other was of a Nazi escaped to South America, who likes to visit a serene painting of a fisherman in an art gallery. Near it hangs an agonised picture of a crucified soul in eternal agony. War crimes detectives hunt the nazi down, and he runs to the gallery as they close in. He runs to where the location of the fisherman paining hung, and begs the cosmos to let him escape capture by entering the painting. He disappears, and the police cannot find him. However a new curator had switched the display of some of the paintings, and the crucifixion now hangs where the fisherman painting had been. The agonised soul in the painting now can be seen to have the face of the nazi: “Beware what you wish for”

Dude, They’re Tearing Down Tim Riley’s Bar was nominated for an Emmy under Outstanding Single Program on U.S. television. Messiah on Mott Street also has a very high imdb rating at 7.6 (8th place for the entire run of the series).

Not sure if you just don’t like sentimentality or whatever, but Tim Riley’s especially was celebrated by critics and fans alike at the time and even now. It’s the third highest rated episode of the series with a 7.8 on IMDB and also – that Emmy nomination.

Tim Riley just seemed overly-sticky to me, the way Serling’s stuff could be sometimes. I think he did better when he gave his work a little sharper edge. Your mileage may – and apparently does – vary. I’m just gald there’s one more person out there who remembers the show!

I can definitely see why some or even a lot of viewers now would see Serling’s writing in that one as preachy/overly-sentimental. Was just pointing out that at the time, it was highly regarded. Maybe it’s one of the best episodes for people who relate to its sentimentality and one of the worst for people who don’t like that kind of writing. Serling also had this really quirky habit of repeating a character’s name over and over and over again in an episode, and in a few of them, it got almost comical (The Waiting Room is one that springs to mind). But God, even at his worst, he was such a powerful writer.

And thank you for writing about Night Gallery! I wish to God people could bring it back into focus again. At its best, it was either a great or not-quite-good-but-interesting Twilight Zone. At its worst – well, it could get really bad. 70s fashion, décor, and music aged really, really badly, and I think that hurts the show, too.

To me what makes the show creepy is that we’re watching the stories and mind of a man in the last half-decade of his life. The final show aired 2 years and 1 month before Rod died. So even though it gets cheesy at times, he was a writer to the end.