The Japanese Giant Monster Golden Era Ends: Space Amoeba (1970)

Earlier this week, while collating ideas for writing about the history of a particular giant monster who recently played a featured role in Godzilla vs. Kong (but who is neither Godzilla nor Kong), an alien sensation suddenly overpowered me. I had to go watch another giant monster movie, one I hadn’t given any attention to in fifteen years: Space Amoeba.

You may have run into Space Amoeba under the title Yog: Monster From Space on television in the 1970s and ‘80s. If you didn’t see it then, chances are you haven’t seen it at all. Although directed by Ishiro Honda, who helmed the original Godzilla and most of Toho’s output of science-fiction and giant monster (kaiju) films during the Golden Age, this tropical monster-bash is remembered today primarily as the final kaiju film made under the old Japanese studio system. It was released to DVD in the 2000s under its original English title, but its profile has remained low with no Blu-ray on the horizon. The three monster leads — Gezora, Ganimes, Kamoebas — have yet to feature in any later movies. Space Amoeba is also just not that good, although far worse kaiju films have managed a bigger cultural impact. (Looking at you, Godzilla vs. Megalon.)

But since Space Amoeba is the swan song of an era and has several famous genre names attached to it, it’s worth another look after so many years. No, it hasn’t improved since the last time I saw it, but I’m spinning my wheels here before peeling out to bigger things.

Economic recession and the explosion of the popularity of television caused theater attendance in Japan to plummet in the late 1960s. The studio system tottered, and in 1970, major studio Daiei (creator of the Gamera series) went bankrupt. Toho, the home of Godzilla and the leader in giant monsters, started to drop its contract talents and slash budgets.

Gezora, Ganimes, Kamoebas Kessen! Nankai no daikaiju (“Gezora, Ganimes, Kamoebas: Decisive Battle! Giant Monsters of the South Seas”) — titled Space Amoeba for English language distribution — slipped under the wire before budget cuts dismantled Toho’s powerful special effects department. Eiji Tsubaraya, the special effects wizard behind Toho’s science-fiction movies, was originally slated to head the VFX for Space Amoeba. But Tsubaraya died in January 1970, leaving the undersea adventure movie Latitude Zero (1969) as his final film.

Teisho Arikawa took over as Space Amoeba’s Special Effects Supervisor. Arikawa had worked as Tsubaraya’s special effects cameraman for years and had supervised the VFX on several lesser films when Tsubaraya was too busy, such as Ebirah, Horror of the Deep. Teruyoshi Nakano, who would handle the special effects on most of Toho’s ‘70s and ‘80s films, served as Arikawa’s chief assistant.

According to producer Fumio Tanaka, Space Amoeba was made to see if the studio could put together a giant monster movie without Godzilla. Toho had released plenty of Godzilla-less monster films, but with the genre narrowing, it might have felt daring to try a kaiju film with no name monsters at all. The script to Space Amoeba seems like an attempt to weld together two strands of kaiju films from the ‘60s: the alien invasion epic (Invasion of Astro Monster, Destroy All Monsters) and the island adventure (Ebirah, Horror of the Deep; Son of Godzilla). The cast is impressive, with many familiar faces from other SF films (Kenji Sahara, Yoshio Tsuchiya, Akira Kubo, Yu Fujiki), and the score is by another Godzilla legend, Akira Ifukube. Arikawa’s effects are solid as well — Tsubaraya taught him well. Yet all this talent adds up to little because the story is paltry and the monsters don’t deliver the thrills. A kaiju film can stumble through thinly developed characters and a trite script as long as the monsters amaze. But Space Amoeba’s three new monsters aren’t up to headliner status.

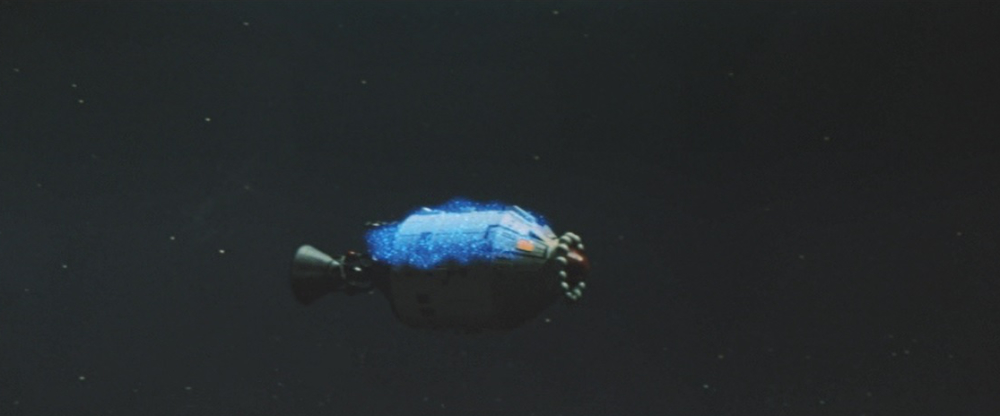

The opening credits sequence introduces our Terrible Trio: Gezora the cuttlefish, Ganimes the crab, and Kamoebas the snapping turtle. The movie then gets into its only “space” part as the uncrewed ship Helios 7 launches toward Jupiter for a three-and-a-half-year mission. The visuals of Helios 7 traveling through space are sublime, on par with the VFX in the 1967 Bond film You Only Live Twice. The rest of the effects aren’t as impressive, but Arikawa made sure audiences got a bit of wonder at the start to hold them over.

Helios 7 doesn’t advance far in its mission. The titular space amoeba (named Yog in the title of the US version from American-International Pictures) seizes control of the capsule and sends it home. That’s all for the space part of the movie. Everything else takes place on a tropical island.

Ambitious photojournalist Kudo (Akira Kubo) sees the landing of the Helios 7 capsule from a plane window, but his newspaper bosses won’t let him go search for it. Fortunately, he gets his chance to go to Selgio Island where the capsule fell when a corporation planning a resort there hires him as a publicity photographer for a survey. Accompanying Kudo is Dr. Miya (Yoshio Tshuciya), who wishes to study animal life on the island and investigate the rumors of giant monsters. Also on the expedition is Ayako (Atsuko Takashi), whose name I had to look up because the dialogue never identifies her or even explains her job. Ayako’s only role is to lure Kudo onto the expedition in the first place, and she has almost nothing to do for the rest of the film. This should give you an idea of how well-developed most of the script is.

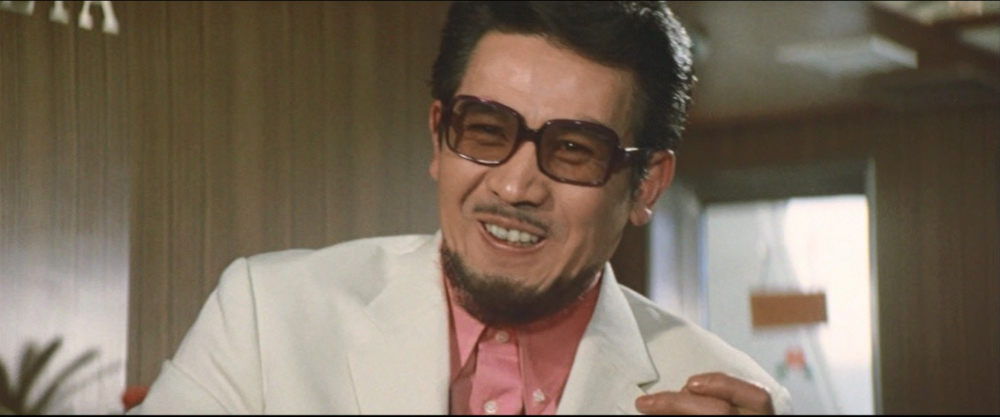

A third person joins the group during the ship voyage to Selgio: corporate spy Makoto Obata (Kenji Sahara), who has disguised himself as an anthropologist. Although the movie doesn’t reveal Obata’s duplicity until later, the character immediately gives off villain vibes because he has those “creepy guy beard and glasses” that were all the rage for Japanese movie villains. No serious anthropologist would try to pull off that combo of beard, glasses, and hat.

And no, Obata’s corporate espionage goes nowhere interesting. All dramatic potential dries up the moment Kudo confronts him halfway through the movie and Obata simply shrugs, admits who he is, and hands back the resort plans he stole.

There are indeed giant monsters on Selgio, and the alien intelligences from Helios 7 take them over one at a time to terrorize the visitors and natives. The aliens seize control of Obata as part of their scheme to conquer the Earth. How they’ll achieve global dominance when all they have are a giant cuttlefish, crab, turtle, and corporate spy on a remote Pacific island is left unexplained, and the aliens end up defeated because they have a weakness to bats and dolphins. I don’t think the planet was in great danger.

Of the giant monster crew, Gezora takes up the first part of the movie. The huge cuttlefish moves awkwardly on land, but the special effects crew shoots it so viewers won’t notice (much) that two of the tentacles are stuntman Haruo Nakjima’s legs holding it upright. Underwater Gezora can look fierce, and the tentacles grabbing at fleeing people work without too many obvious wires. There’s hand animation thrown in when the tentacles need to move fast, and the effect is better than it needs to be.

Ganimes the crab arrives in time to chase a few people, quickly die, then have an unexplained resurrection at the finale. Kamoebas, a turtle with Ram-Action Head™, pops up for the conclusion, again chasing the heroes but then getting into a tussle with Ganimes during the final minutes for the film’s only monster fight.

Space Amoeba has some class and gloss left over from the dying studio system. Compared to next year’s Godzilla vs. Hedorah, it’s almost a David O. Selznick production. Yet I’d rather watch Godzilla vs. Hedorah for entertainment value, because Space Amoeba is mostly a bore despite the dimming studio luster. The story is a haphazard lurch based on characters managing to make correct guesses just to get the plot moving again, and most of the “action” is characters dashing through the jungle to get away from bland monsters.

Every few scenes, Dr. Miya makes a hypothetical stab at explaining what’s happening on Selgio Island, but never manages to clarify things. Were there always giant monsters wandering around the island, as the beginning of the film and the native legends seem to indicate? Or did the alien infiltration make them larger, as Dr. Miya suggests? If so, why didn’t Mr. Obata get embiggened when they possessed him? That might have been fun. And where did the second Ganimes come from? The ultimate showdown against the aliens involves the heroes trying to locate a cave with bats (animals with ultrasound are the space invaders’ one weakness) before the alien-controlled Obata can torch all the caverns to be bat-free. It’s a silly, pathetic turn of events for a finale that makes the alien invaders look like amateurs.

Director Honda hasn’t much to work with, and the only intriguing character, Mr. Obata, is unlikable and not someone who can seize our sympathies in his struggle to fight off the effects of the invader. It’s not the fault of actor Kenji Sahara; he’s excellent at playing oily villains and there are echoes of the memorable corporate sleaze he played in Mothra vs. Godzilla. But it’s criminal how the movie does nothing with the other interesting actors, especially Yushio Tsuchiya, who’s stuck in the rote scientist role. Tsuchiya made a tremendous impact on Japanese science-fiction films with his often bizarre roles: the Controller of Planet X in Invasion of Astro Monster, alien-possessed astronauts in Battle in Outer Space and Destroy All Monsters, and a Godzilla-worshipping technocrat in Godzilla vs. King Ghidorah. He also starred in several Akira Kurosawa films, including an obscure project called Seven Samurai. So why is he given nothing to do here? I guess this is what happens when a studio system unravels.

I understand what the filmmakers were trying to achieve with the three monster stars. The popularity of superhero shows like Ultraman had shifted kaijus toward designs that were alien but also anthropomorphic. The monsters in Space Amoeba shove back the opposite direction: they’re based on real sea creatures and echo an era of monsters grounded in recognizable biology and animalistic drives. The monsters are also designed on a smaller scale than in the Godzilla movies, around twenty meters rather than fifty, which allows for more detailed miniatures and specific threats against the human characters. All good in theory. In execution, Gezora, Ganimes, and Kamoebas don’t provide much excitement aside from knocking down huts and chasing after the bland leads and faceless natives. The effects are superior to the kaiju films from the rest of the decade, but Eiji Tsubaraya’s magic touch is absent.

Gezora the Big-Eyed Cuttlefish has some personality, or maybe it’s just that it gets the most screen time, and Kamoebas’s thrusting head is the right level of goofy, but there’s not much else to say about these monsters. The only fight is between Kamoebas and the second Ganimes once the aliens lose control over them (damn bats!). But neither monster has built up enough audience investment to make their tussle and final topple into a volcano anything but the required curtain-closer for a kaiju film. The monsters are dead, you can go home now.

I can’t even recommend Akira Ifukube’s score. An ethnic drumbeat created with synthesizer at the opening promises quirky experimentation, but the music stays on autopilot. Ifukube dusts off and tweaks his native chant from King Kong vs. Godzilla, which I suspect was a time-saving move.

This may sound blasphemous for a fan of giant monster movies to say, but I think Space Amoeba would have worked better if Jun Fukuda had directed it instead of Ishiro Honda. Fukuda handled the island adventuring in Ebirah, Horror of the Deep and Son of Godzilla and showed skill with action-based storytelling. Honda doesn’t feel as invested in this tropical island business. The direction is routine, workmanlike. Maybe if Honda made this film earlier in his career he would have done something more with the relationship between the Selgio natives and the Japanese, who had garrisoned the island during the War. This bit of story information only serves to explain how the heroes find a store of gasoline they can use against Gezora.

As the film rambles to its conclusion, one of Honda’s favorite themes struggles to emerge: the human race coming together against adversity. But it feels like a toss-away joke when Kudo delivers this final line:

The united forces of earth creatures — porpoises, bats, and men — destroyed the invaders. Will the people believe this story?

Honda wouldn’t direct another feature film for five years. Thus endeth the Golden Age of the Japanese Kaiju movies.

Ryan Harvey is the author of the novel Turn Over the Moon. He lives in Southern California where he studies Godzilla, Edgar Rice Burroughs, and for some unfathomable reason also performs improv comedy.

Ludicrous it may be, but I actually like Yog, the Space Monster, as I saw it in a theater double billed with War of the Gargantuas in about 1971. Personally I still find the giant squid curiously effective, even when it is WALKING about in broad daylight… Probably it is in part because of having seen it when young–I still think War of the Gargantuas (Furankenshutain no Kaijû: Sanda tai Gaira) is amazing even if I can’t recommend Yog to too many people.