“Is There Anybody There?”: James Gunn’s The Listeners

The Listeners by James Gunn

First Edition: Scribner’s, October 1972, Jacket design Jerry Thorp

(Book Club edition shown)

The Listeners

by James Gunn

Scribner’s (275 pages, $6.95, Hardcover, October 1972)

Jacket design Jerry Thorp

The late James Gunn, who died just last year, became an SFWA Grand Master in 2007 and was inducted into the SF Hall of Fame in 2015, both recognizing his achievements in science fiction. His individual awards include an Eaton Award for lifetime achievement as a critic (1982), a Pilgrim Award for lifetime contribution to SF and fantasy scholarship (1976), and a Clareson Award from the Science Fiction Research Association (1997).

So while Gunn wrote a good amount of fiction, some fifteen novels and a similar number of story collections, it’s fair to say his profile was higher as a nonfiction writer and critic than for his fiction. His critical work includes Alternate Worlds: The Illustrated History of Science Fiction (1976), which presumably triggered the Pilgrim Award (but predated the Hugo category for nonfiction or related book), and Isaac Asimov: The Foundations of Science Fiction (1982, which did win a Hugo Award). He also edited the prominent series of anthologies The Road to Science Fiction (1977 to 1998), and was closely associated with the Campbell and Sturgeon awards organized at the Center for the Study of Science Fiction in Lawrence, Kansas, where spent most of his life in academia.

The closest he got to major awards recognition for his fiction was the novel considered here, The Listeners, from 1972. It came in second for the John W. Campbell Memorial Award, in that award’s first year, to Barry Malzberg’s Beyond Apollo, though it was not nominated for a Hugo or Nebula award. (Neither was the Malzberg.)

The Listeners was, if not the first, then certainly the most significant SF novel to date depicting the idea of SETI, the Search for Extra-Terrestrial Intelligence, an idea developed by scientists, as well as SF writers, beginning in the 1960s.

Gunn vs. Sagan

A couple points are worth mentioning before turning to the novel itself. Online reviews (which I rarely look at, except in this case to see if any of them identified the issues I had with this current Reputation Books edition) wonder who influenced whom considering this book and Carl Sagan’s better-known 1985 novel Contact (later a 1997 film with Jodie Foster). The influence seems to have gone both ways. Sagan acknowledged Gunn’s novel; Gunn was inspired mostly by Walter Sullivan’s We Are Not Alone (1966) but also by Sagan’s early nonfiction, including a book with I.S. Shklovskii, Intelligent Life in the Universe from 1966. (I’m planning to cover Sagan’s novel in my next column here.)

Issues with the recent edition

Second, one reason I thought to cover Gunn here is that it is available in a recent new edition, a trade paperback from Reputation Books in 2017, shown below. (I usually though not always try to avoid covering books that are way out of print and can only be read by tracking down used or collectible copies.) However there are some issues with this Reputation edition, which I discovered as I read it and compared it to my 1972 book club edition of the Scribner’s edition.

- The Reputation edition omits the original’s table of contents, listing six sections or chapters with “Computer Run” interludes. (Thus one Amazon reviewer complained the second chapter in the edition he read didn’t advance the plot; it wasn’t the second chapter, but an interlude.)

- These “Computer Run” interludes are comprised of quoted passages from the classics, from contemporaneous nonfiction books and essays, and occasionally from classic science fiction stories. There are also passages about the 21st century world outside the SETI search, which in the original hardcover were set in FULL CAPS, as if a news teletype. In the Reputation trade paperback these become passages of full lower case, more appropriate to stream of consciousness ruminations. Other textual infelicities include omitting blank line breaks in the narrative that indicated passage of time or change of locale.

- More incidentally, the acknowledgements page, crediting sources for some of the in-line quotes and Computer Run passages, is moved from the copyright page in the hardcover, to the very end of the trade paperback, following the translations.

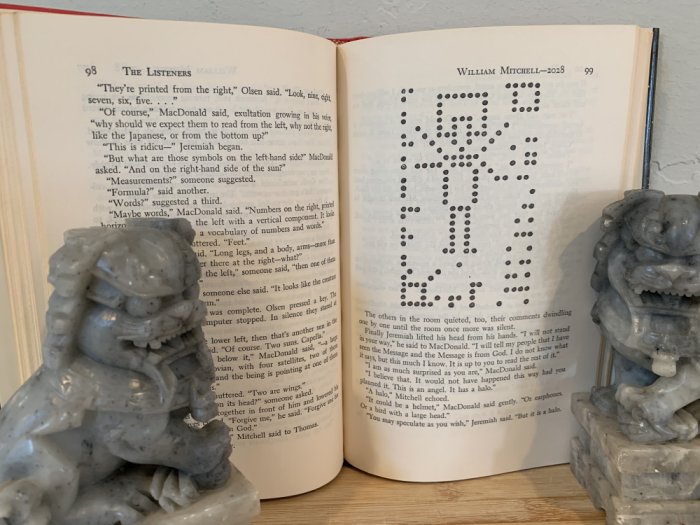

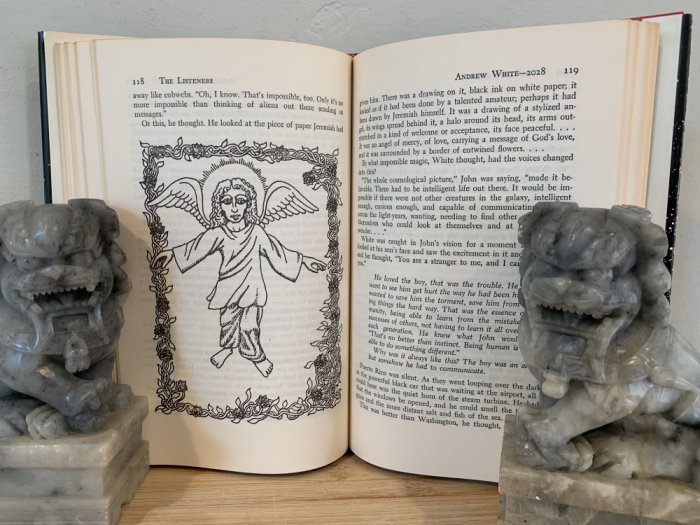

- Most crucially, the original hardcover edition *shows you* the messages that are detected, as they are deciphered into grids of dots and blanks. The Reputation edition omits these entirely. True, the diagrams are discussed by the characters, but it helps greatly to see what they’re describing. And in addition to the dots and blanks grids, there are two interpretive drawings of one of the messages whose descriptions in the prose don’t do them justice.

The Listeners by James Gunn

Reputation Books, May 2017, Cover art Michele S. Nettleton

In the walkthrough that follows, I’ll include photographs of the diagrams and drawings from the original hardcover (at least, my book club edition of it).

Gist

Beginning in 2025, a SETI project at Arecibo in Puerto Rico has been under way for 50 years and has found nothing. When a message is finally detected, the scientists deal with pressure from politicians and religious leaders about what it means and whether or not to reply.

Take

This is a striking book not just for the seriousness with which it deals with the theme of SETI, but also for the bittersweet consequences of finally detecting a message, for the introspection and angst of some of the characters, and especially for how Gunn places the search in the context of real scientific speculations of the time, against a background of philosophical and poetic passages from the classics (including some SF “classics”), and amid a setting a 21st century world that is steadily getting better.

Walkthrough [[ with comments ]]

The six chapters of the book (not including the “Computer Runs”) were published as novelettes beginning in Galaxy in September 1968, the others in 1971 and 1972, one in F&SF and the others in Galaxy. The second and third, as ordered in the book, were published out of order in the magazines.

1, Robert MacDonald—2025

- The opening epigraph is “Is there anybody there?” said the Traveler. Of course citing the famous Walter de la Mare poem “The Listeners” which provides the book’s title. (Even I, no student of the classics, recognized this one, without having to check the acknowledgements.)

- Bob MacDonald is the Director of the “Project,” which has been under way for 50 years, so far with no results. Morale is a problem. He and his staff — Saunders, Olsen, Sonnenborn, each with his own personality and interests — work in a low concrete building near one antenna that points up into the sky, and the big antenna sunk into the ground. (This of course is the famous Arecibo Observatory, built in 1963, that in 2020 suffered a catastrophic collapse.) Now MacDonald, or Mac as the staff calls him, prepares for government hearings to renew the Project’s funding and goes through the day’s mail (requests for interviews; letters from cranks). And then reviews the computer analysis of the previous night’s data. Always nothing.

- This chapter is replete with in-line quotations from poets, playwrights, philosophers — Cervantes, Goethe, Donne, Dante, Horace — given in the original languages. (Translations of all the non-English of these are given at the end of the book.) These echo Mac’s thoughts, sometimes indicated explicitly in the text, others only by implication. The surface justification for these is the MacDonald was a linguist early in his career (and presumably trained in the Classics), before turning to engineering and this Project. Some readers presumably find these pretentious, though I think they are effective in indicating, as I said above, how this search for other intelligence in the universe speaks to the biggest issues humanity has ever faced, as pondered by all those poets, playwrights, and philosophers.

- At the end of the day Mac drives home to his hacienda a few miles away, where his long-suffering wife Maria Chavez is asleep. (There is a mention of sleeping pills carefully dispensed.) He wakes her, he fixes dinner, they make love. And then he returns to the Project, where all the action occurs at night. He listens to the raw signal, all noise, perhaps a babble of distant voices. (Matthew Arnold is cited here, about the “melancholy, long withdrawing roar… ”)

- On Saturday evening [page 27 of Reputation, before “The house was brilliant… ” is where a blank line break should be, for example] Mac and wife host a party. While the women gather at the bar or in the kitchen, the men chatter about hydrogen-emission lines, quantum noise, what if nobody’s there? What if everyone’s listening, no one sending?

- Again Mac returns to work late at night, pondering that even if they get a message, they’ll all likely be dead before an exchange could take place. What sustains such perseverance? It’s akin to religion: what drove those builders of cathedrals, whose work would not be done in their lifetimes?

- He gets a call — there’s been an accident with Maria. He rushes home. She has slashed her wrists. A doctor takes her to the hospital.

- The next day, bereft and feeling a failure, Mac returns to work, writes out a hasty message. His staff, even a janitor, try to talk him out of it. A call from the doctor: Maria will be OK. So Mac takes the message he wrote — a resignation — and tears it up.

- [[ From the beginning there’s the introspective flavor of, say, Silverberg, here; this is not a story of brave scientists persevering against all odds, but a passionate quest despite all self-doubts. A balance of understanding the scientific odds of other civilizations being out there, against the personal cost of spending one’s life on a cause with no guaranteed outcome.

- The book’s attitudes reflect its time, in a couple ways: there are only a couple incidental female characters, both incidental; and everyone smokes. ]]

Computer Run (1)

- Quotes from Harlow Shapley, Tsiolkovsky, Tesla, Eiseley, Sagan, Bracewell, Drake, et al.

- And from H.G. Wells [the Reputation edition has “H.G. Well”] and Murray Leinster.

- [[ These sections remind me that at one point Kubrick and Clarke planned to open 2001 with interviews with experts — likely some of the same ones cited here — to justify the idea of extraterrestrial intelligence, before the story began. I can’t imagine a duller way for any movie not a documentary to open. But such passages as interludes in the book work pretty well, I think. ]]

- [[ Why are these breaks headed “Computer Run”? By the end of the book the on-site computer has become one of the most powerful on Earth, and apparently influenced by… (avoiding spoiler, for now). ]]

2, George Thomas – 2027

- Thomas is a magazine writer who’s come to profile MacDonald for Era magazine, frankly admitting he thinks the project is a boondoggle and should be killed. The only thing that would change his mind is a message. MacDonald gives him a tour of the facility.

- In this chapter in-line italicized passages reveal Thomas’ drafts for his article about the facility, about MacDonald, and so on, in stately objective tones.

- Thomas visits MacDonald’s home and has dinner with him and Maria. She perceives he is a bitter man; he has written a novel, done a famous translation, yet has settled to become a journalist. Meanwhile Mac and Maria now have a son, a few months old.

- Thomas is relentless in thinking those working for the project are fools. Mac lets Thomas listen to the babble of voices. It’s hypnotic. But Thomas thinks it a fraud, and is genuinely angry.

- And so MacDonald announces — they’ve received a message! Thomas is cynical about this apparent coincidence; Mac responds that journalists are here every week, he just happened to be the lucky one.

- They listen to the message: lots of popcrackle noises interspersed by snatches of speech and music, in English and other languages.

- They realize these are recordings of broadcasts from the early days of Earth’s radio broadcasts, from the 1930s. They’ve apparently been captured from an area of space near the star Capella, 45 light years away, and bounced back. Perhaps some civilization out there has been listening all along? [[ Somewhat like Clarke’s sentinel. ]] Is there another signal in the static, an actual message? Should they announce it?

- Suddenly converted, Thomas insists that they do. He’s is now anxious to get the word out, do a series of profiles about the Project, help people understand what intelligent creatures from another world might be like.

Computer Run (2)

- Yeats, C.S. Lewis, et al; passages from van Vogt (“Hopelessly, Coeurl crouched…”) and Campbell (Don A. Stuart); a list of star names.

- And in this section, teletype news about the outside world, which is getting better — ZPG, zero population growth, and so on — and also about a sect called the Solitarians, who believe that humanity is alone in the universe and so the message can’t be real.

3, William Mitchell – 2028

-

- William Mitchell works for Thomas, of the previous chapter, and his fiancée is the daughter of Jeremiah, the leader of the Solitarians.

- The chapter opens on a domed stadium where Jeremiah speaks to a vast audience: “We are alone… That is the message from God.”

- The three men, MacDonald, Thomas, and Mitchell, have come to talk with Jeremiah, concerned that his meetings are turning people against the Project before the message can be deciphered. Now that the Project has succeeded in receiving a signal, Jeremiah is its most serious threat; their beliefs threatened, the Solitarians want the Project stopped.

- [[ In this chapter section breaks are indicated by gradually expanding patterns of dots and blanks, omitted in the Reputation trade paperback. ]]

- The three men return to Arecibo, where they listen to a portion of the message. Is it Frank Drake’s idea about a message built of a combination of primes? Mac has a hunch that this is the solution, and wants to get Jeremiah here, to witness the deciphered message before they even verify it themselves.

- And so Jeremiah comes to Arecibo, skeptical and stand-offish. MacDonald patiently explains their methods, how any discovery if valid would be checked by others. (Unlike believers, who never receive identical messages, p135.8.) The nature of the universe is the same everywhere. Jeremiah concludes that Mac is sincere, but deluded.

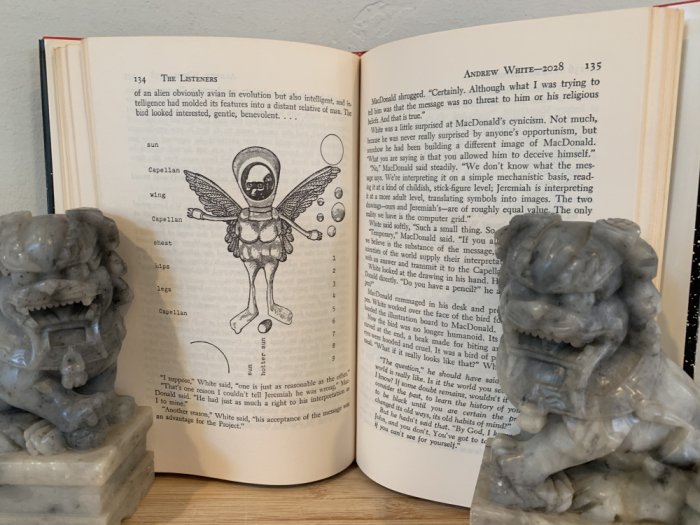

- And then the computer runs analysis on combinations of prime numbers, one combination after another, until a diagram appears. A figure, pointing, two suns (upper right and lower left), something on its head?

The Listeners by James Gunn —

The Capellans’ first message.

- Jeremiah (like Thomas before him) is instantly converted — he sees a message from God. An angel. He apologizes for doubting, and departs.

- After which members of the staff make different suggestions about what the diagram might mean. Each person interprets it differently.

Computer Run (3)

- News reports about various social and technology advances: reduction of incarceration; holovision.

- NASA predicts possible chaotic reactions in society to news of the aliens, followed by several reports of people becoming hysterical and panicking.

4, Andrew White – 2028

-

- This is about the president of the United States, a black man (ironically given his name), who has a contentious relationship with his son. The son is too idealistic he thinks; President White perceives politics as warfare, and the racial struggle as eternal.

- Now — virtually the same day as the previous chapter — MacDonald phones White about the message, and their interpretation. The president is instantly alarmed, wants no news of this to get out, and wants to intercept Jeremiah before he says anything.

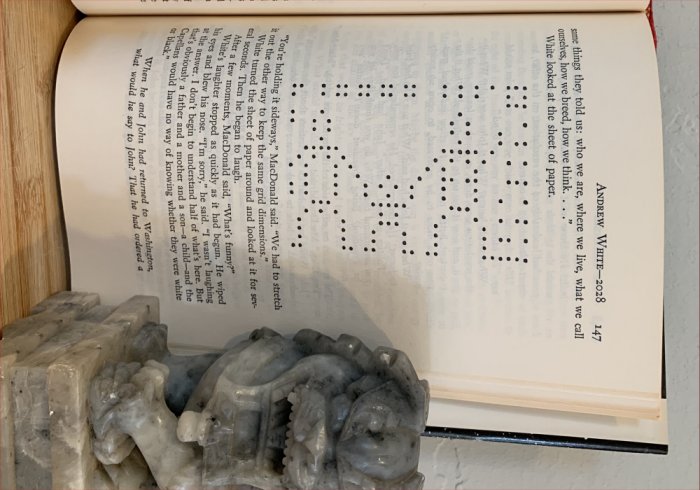

- President White and his son John fly to Texas to intercept Jeremiah, but Jeremiah is defiant, insisting he will fulfill his mission this evening. He hands White a drawing of an angel — his own interpretation of the black and white grid.

The Listeners by James Gunn —

Jeremiah’s interpretation of the first Capellan message

-

- White and son go on to Arecibo, where MacDonald explains about the message. White sees potential aggression, thinking his son is wrong to see the world as benign. MacDonald shows another interpretation of the message: an avian alien in a helmet.

The Listeners by James Gunn —

Robert MacDonald’s suggested interpretation of the first Capellan image

-

- MacDonald insists this is a scientific matter. He wants to release the message to the world, let scientists come up with an answer, and send a reply to the Capellans. The president thinks scientists are naïve; the Capellans might be predatory.

- News comes in about riots, traffic jams, global alarm. White thinks this confirms his view of the world, one his son John has never seen.

- MacDonald wants to send true information out into the world, to make people understand the significance of this discovery. And sending a reply would… give his life meaning. And it would leave something for his (now infant) son. Sending a message will bring peace to the world.

- Calls come in from ambassadors. The Chinese says: don’t reply. The Russian says: they are composing their own reply (though this notion or its consequences are never mentioned again).

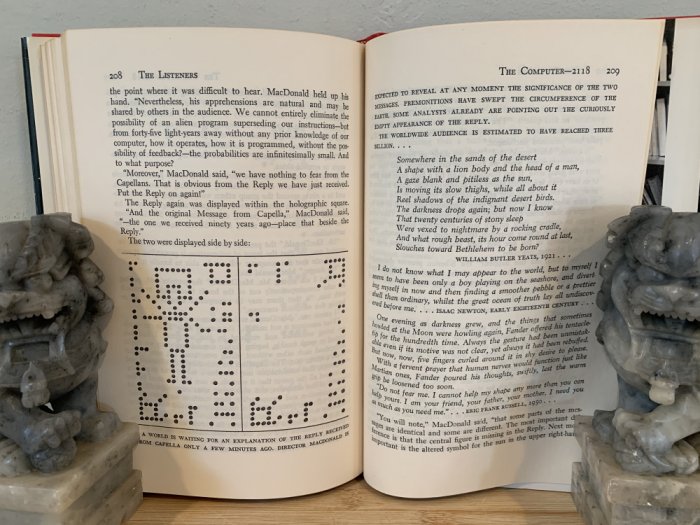

- There is discussion about the function of government: to eliminate poverty and disease, to create a stable social system, to manage change. White is afraid of the change this project would bring; he wants to shut it down, gradually. Even if the answer wouldn’t come for 90 years. Mac promises to handle the project carefully, but refuses to simply shut it down. He shows the president a draft of a reply signal: similar to theirs.

The Listeners by James Gunn —

Robert MacDonald’s proposed reply to the Capellans (shown sideways in the book, here turned)

- And then the President’s son John has a sudden insight about the message. Do the symbols for the two Capellan suns mean one is about to go nova?

- Mac suggests an answer of solidarity. A human and a Capellan joining arms. President White (perhaps driven by the inspiration of his own son) agrees [[ another abrupt conversion! ]]: send the message.

Computer Run (4)

- Sagan’s speculation about interstellar evangelism (as Europeans tried to convert the heathens of the New World), and other topics. Comments by Kahn and Wiener from 1967 about how if the need for work goes away, so too might many people’s contact with reality [[ anticipating a theme of Yuval Noah Harari ]].

- Current event notes include a bestselling book called “A Boy and His Bird”; how gross national product is up, due to automation and fusion; about a Gibraltar Dam; holovision.

5, Robert MacDonald – 2058

- It’s now 30 years later, and this Robert MacDonald is the estranged son of the first. He has come to Miami, from New York by bicycle and bus, and has a friendly encounter with an attractive girl. From Miami he hitches a ride on a boat to Puerto Rico.

- His modes of travel, and thoughts about how the big cities are more like villages, imply something suggesting, I think, that the world is becoming more peaceful, less complex and hectic. Robert senses the world is waiting for something, perhaps the Reply; but what kind of Reply would be worth the waiting?

- He stops by his house, where he was born. Someone else lives there now, but lets him look around. It’s not the same.

- He cycles on toward the Project, meets Olsen, now a frail old man, and John White (the President’s son in the previous chapter) who now works here. It becomes clear they have summoned Robert here, now that his father has died. The younger Robert says he hasn’t read anything about the Project in 20 years, nor, when the others ask, has he even read the letters his father has sent him over the decades. He has no interest in any of his father’s things.

- They offer him a job, any job. Despite the younger Robert’s protestations about his disinterest, he has in fact studied linguistics and computer programming, almost as if preparing to succeed his father. This is his chance to be part of something bigger than an individual life.

- They give him a tour, show him the new computer, one of the largest in the world. And they play him a tape, from across the decades, from this room where everything has been recorded: excerpts of key events from all the previous chapters and beyond, to the aftermath of the first Robert MacDonald’s death, and a final visit from Jeremiah, in tribute.

- The younger Robert keeps seeing the image of his father sitting in a chair… Does anyone else see this? Setting this aside, he tells them: No, he’s not ready to take a job. There’s a girl he wants to find, and he has some letters to read.

Computer Run (5)

- Passages from fiction by Sturgeon and Simak (“…and me back into a man”); speculations on the big bang, and how space-faring races would exchange data; and current news about how only the professional classes working long days anymore, about leisure time and sensory cubes, about the rise of a dilettante class. And how the basic questions of science might be different for an alien race.

6, The Computer – 2118

-

- And now it’s 60 years even later, and observers from all over the world gather at Arecibo to be present for the Day of the Reply, the first time a return message might be received from Capella. [[ I don’t think it’s plausible they could calculate so precisely a particular day. ]] A new auditorium has been built. The Director is now William MacDonald, 57, third director in the family. He speaks to the “citizens of the world” watching live, cautioning them how the message may not arrive for days or weeks.

- Someone in the audience asks about the rumored “presence” in the computer room; is this a hologram created by the computer? William dismisses the idea.

- (In this section, Computer Run-type passages appear inline with the narrative: Whitman, Wells, Leinster (“swap ships!”), Yeats, et al.)

- A new signal is indeed received right away, and compiled and displayed by the computer. Someone in the audience warns of the danger of an alien signal possibly taking over the computer; the director dismisses this as highly implausible.

- The message, another dot and blank grid, appears, similar to the first one, but lacking the central figure. Further, the symbols for the two suns are now identical.

The Listeners by James Gunn —

The first and second messages from the Capellans, side by side

-

- They realize they made an incorrect assumption about the idea of a nova. Perhaps instead both stars have become red giants — and the Capellans are now dead and gone. The Message was automated.

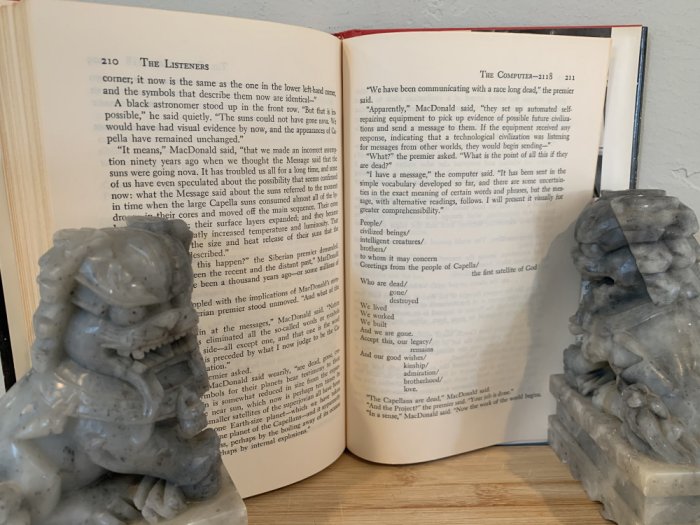

- Sure enough, a text message appears: “People/ civilized beings/ … greetings from the people of Capella/ the first satellite of God/ Who are dead/ gone/ destroyed…”

The Listeners by James Gunn —

The Capellan’s final, text, message [Click to expand]

- The signals go on: the entire record of an alien civilization is being sent, for humans to examine and comprehend.

- MacDonald ponders that when it finishes, the “silence will surge softly backward” before a new search begins.

- And the last line of the book is: “By that time the computer would be at least half Capellan. No one but the computer would realize this for half a century and by then the Project would pick up a message from the Crab Nebula.”

Comments

- The notion of communicating with aliens by signals or images built of combinations of prime numbers is now a well-known one, though Gunn’s wasn’t the first treatment of it in SF.

- Just as familiar is the depiction of the clash between science and religion. The former wants to explore; the latter is sure it already has the answers, resists exploration, and rejects the findings — unless they can be interpreted as supporting existing dogma.

- Much more unusual in this book, as I’ve said, is the cultural milieu, the appeal to the ideas of the great poets and philosophers, that place SETI as one of the great projects of human history.

- Finally, it’s worth reflecting that this idea, the beginning of the “search,” is now some sixty years old, and the results to date are, unlike as in this novel, zero.

Mark R. Kelly’s last review for us was of Isaac Asimov’s Fantastic Voyage (closely comparing it with the film Asimov’s novel was based on). Mark wrote short fiction reviews for Locus Magazine from 1987 to 2001, and is the founder of the Locus Online website, for which he won a Hugo Award in 2002. He established the Science Fiction Awards Database at sfadb.com. He is a retired aerospace software engineer who lived for decades in Southern California before moving to the Bay Area in 2015. Find more of his thoughts at Views from Crestmont Drive, which has this index of Black Gate reviews posted so far.

I haven’t read this since I first got it out of the library, probably shortly after it came out. I remember being impressed by its seriousness and quietude, and moved by the ending. I think it’s the best fiction Gunn ever did.

His next nearest approach to a major fiction award was with “The Giftie” (1999) which was shortlisted for the Sturgeon. (“The Giftie” is good, though not really great.) I think his “immortals” stories are his other best fictional work.

(Interestingly (or perhaps not!) Capella is the center of human interstellar civilization in Carolyn Ives Gilman’s fine first novel HALFWAY HUMAN.)

Thank you, Mr. Kelly, for including the illustrations from the 1972 edition. Just would not be the same without seeing that angel.

Quite an essay– in fact you dive so deep that I’m not going to finish reading it because I intend to read the book itself! I think I have the Book Club edition, but am not 100% sure.

Well, I have an e book that has the Computer Run segments italicized but lacks the images… I think, before I actually read the book — or read more fully your review — I will see about inserting them. Thank you very much for providing the images in editable form.