How Sword and Sorcery Brings Us To Life

|

|

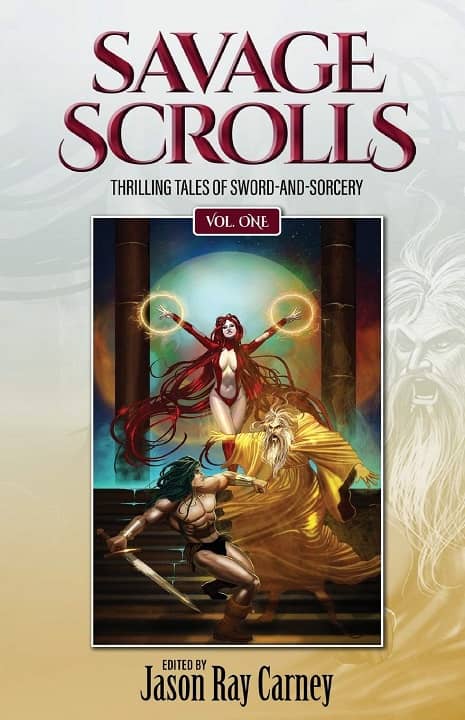

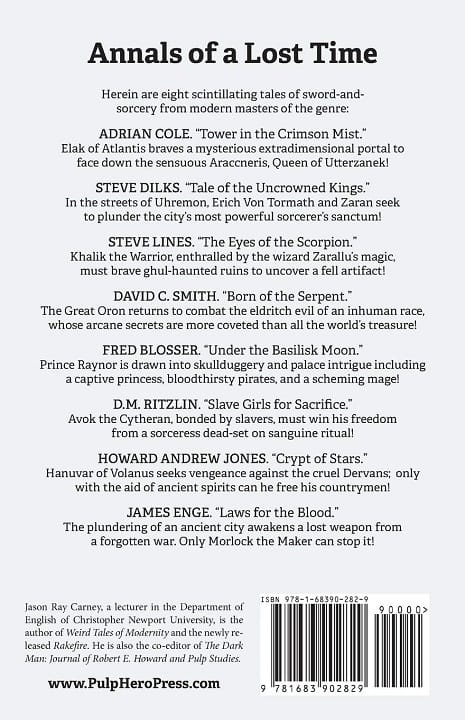

Savage Scrolls, Volume One, edited by Jason Ray Carney (Pulp Hero Press, 2020). Cover by Jesus Lopez

When I was working on the introduction to Savage Scrolls, I re-read all of Lin Carter’s Flashing Swords introductions. Something caught my attention: Carter starts Flashing Swords 1 with an epigraph, a stanza from William Morris’s six-stanza poem, “Prologue of the Earthly Paradise.” It is a beautiful apologia of fantasy literature. The speaker, Morris, attempts to comfort his reader, a weary, disenchanted worker, by celebrating the transformative nature of the heroic poetry of premodernity. But Morris does so hesitantly:

The heavy trouble, the bewildering care

That weighs us down who live and earn our bread,

These idle verses have no power to bear.

Morris is not making hyperbolic claims for the power of literature here; he is no Percy Shelley, claiming “Poets are the unacknowledged legislators of the world.”

No. Morris is comparably modest. Do you have bills to pay? Taxes to file? Mouths to feed? Alas, admits Morris, imaginative literature will not help you bear these miserable burdens. But it might help in other, nuanced ways.

Let it suffice me that my murmuring rhyme

Beats with light wing against the ivory gate,

Telling a tale not too importunate.

This is a compressed, enigmatic passage, worth mulling over. Morris seems to prevaricate. The strangeness of his claim for poetry’s utility could be lost in his flurry of ornamental syntax and figures of speech. So, let’s slow him down: Morris says that his poetry “beats with light wing against the ivory gate” of paradise. What does it mean to spin a tale that “wings lightly” or transports the reader to the very gates of paradise? Is Morris suggesting that poetry can take you to paradise? Really? Can poetry fly you to Valhalla? Is poetry a SpaceX rocket?

We are familiar with this bizarre trope, the idea of poetry as a form of metaphysical transportation. How does Dante, for example, get to hell? He is not brought there by angels but by the poet, Virgil. Imaginative literature might not pay your bills but, for Morris, it might take you to the very gates of paradise. That’s something.

There’s more to this passage. Morris gives us a hint regarding the type of poetry that achieves this quasi-magical power to transport: it is “not too importunate,” tendentious, insistent, or persistent. In other words, the poetry that can most readily transport us to the very gates of paradise is the poetry that does not make demands.

This is another strange claim. How does poetry make demands on you? Is poetry a kind of scolding mother? A judgmental vicar? For the contemporary reader of Morris’s poem, these analogies would not have rung false. A typical middle-class reader, I dare say, had been taught by 1890 to assume the position of a scolded child or church parishioner when reading poetry. The Victorian Age had turned poetry into something like a bitter medicine meant to make you a better person and the world more just. Upwardly mobile industrialists read it to civilize themselves, to blunt their edges, to incentivize them to help the poor, the downtrodden, the meek. Not to experience beauty.

Some additional historical context might be useful here: 1890 was the beginning of England’s “decadent” period. Less civically-minded writers like Oscar Wilde, enamored of French writers like Baudelaire, sought to refute literature’s dominantly accepted “social improvement” function, one promulgated by Victorian Sages such as Matthew Arnold, who saw art as civilizing, as a tool for maintaining social order. Rebutting Arnold and Victorians like him, writers like Wilde and Morris held that literary art should, first and foremost, bring delight and beauty and even escape from the drab, stultified world of late-19th-century industrialism. Thus, when Morris celebrates a “not-too-preachy poetry” that will “wing” you to paradise, he is echoing Oscar Wilde, who, in his famous “Preface to the Picture of Dorian Gray,” boldly asserts, “There is no such thing as a moral or an immoral book. Books are well written, or badly written,” and “all art is quite useless.”

For 21st-century readers of pulp fiction (and sword and sorcery specifically), this view of literary art is a horn of mead to a parched throat. Fans of pulp-origin sword and sorcery, the kind published in Savage Scrolls, read and write in a time when social activism and imaginative literature are bound together, from the left and the right. Legitimate concerns about representation of difference and the perpetuation of xenophobia, sexism, homophobia, and racism seem to make pressing demands on writers in genre. New literary works are sometimes judged based on their moral vision, their political utility, and other non-aesthetic elements to which the sword and sorcery writer often seems indifferent (though not always).

In our current context, Morris’s pregnant question to his readers echoes in the mind of sword and sorcery fans everywhere: “Dreamer of dreams, born out of my due time, / Why should I strive to set the crooked straight?” Should writers strive to set the crooked straight, to fix the broken world? Or, like Morris, should it suffice that “not-too-importunate” tales “wing” us to paradise?

Perhaps even more pressing is the question: why go to paradise, to Hyboria, to Newhon, when there is so much to fix here? And to writers: why write sword and sorcery? Why be Robert E. Howard when you could be George Orwell? “When I sit down to write a book, I do not say to myself, ‘I am going to produce a work of art,’” writes Orwell in his famous essay defending political literature, “Why I Write.” Orwell continues, “I write it because there is some lie that I want to expose, some fact to which I want to draw attention.” Alas, from a certain literal perspective, fantasy literature is a nest of lies. Why prefer the imaginative literature of the unreal to socially-engaged literature?

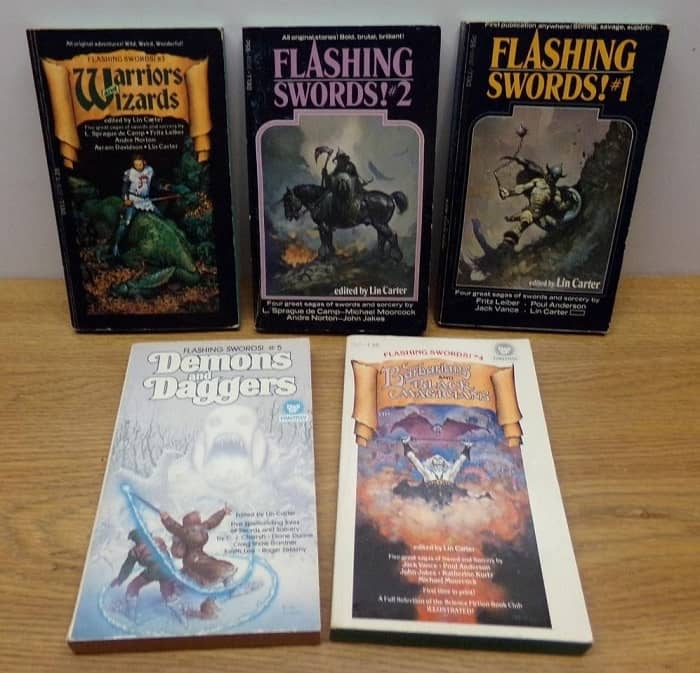

Lin Carter’s Flashing Swords anthologies (Dell Books, 1973-1981)

In the introduction to Flashing Swords 5, Lin Carter tries to answer this very question but admits to simple recalcitrance on his part:

I’ve long […] given up trying to figure out why I prefer such fantasies to other kinds of fiction. It’s not that I disapprove of social realism or science fiction or the formal historical or mystery yarn or anything else. Perhaps it is quite simply that in the imaginary world fantasy, the author has the widest possible room to swing his imagination: he can invent worlds where magic works and the hard sciences just plain don’t; worlds ruled by gods or wizards or elves; flat worlds, hollow worlds, worlds that are real only in dream. In other words, Sword & Sorcery gives the broadest conceivable scope to the playfully inventive imagination.

Put another way, sword and sorcery allows us to play, to forget the real world, and to dwell for a time in a Neverland. From the perspective of Arnold and Orwell, decadents like Morris and Wilde (and Carter) appear as negligent of their artistic and social duty, Peter Pan figures at best; or, less flattering, Nero-like privileged eccentrics who fiddle while Rome burns. Fans of sword and sorcery are either puerile or cruelly indifferent to social ills.

That’s not much of a choice and neither casts sword and sorcery in a positive light. Can we lodge a defense of reading and writing sword and sorcery? Perhaps the perspective of a partisan to imaginative literature will help, and there are none more sincere than H.P. Lovecraft. For Lovecraft, the didacticism and social activism of Arnold and Orwell is reprehensible; additionally, for Lovecraft, the aestheticism of Wilde and Morris is just too humble. Elaborating on and maximizing their defense of imaginative literature, Lovecraft asserts,

The imaginative writer devotes himself to art in its most essential sense. It is not his business to fashion a pretty trifle to please the children, to point a useful moral, to concoct superficial ‘uplift’ stuff for the mid-Victorian hold-over, or to rehash insolvable human problems didactically.

In other words, it isn’t the imaginative writer who is negligent but the social realist, the activist, Orwell and Arnold. So the battleline is drawn between the aestheticists and the socially-engaged, and whole genres–like sword and sorcery–are enlisted into the fight by tendentious opportunists.

I find neither extreme appealing because they aspire to render the whole story, and so fail. For example, John Steinbeck’s The Grapes of Wrath (1939) is an artful activist novel, but Robert E. Howard’s “Red Nails” is an equally profound meditation on realpolitik, tribalism, and the perennial themes of human conflict, truly insightful in the years preceding World War II. But what sword and sorcery writer would claim they are devoted to art “in its most essential sense”? Steinbeck had no problem adopting the pose of the “artiste,” but this would have been an awkward pose for Howard. Writing to Farnsworth Wright, his editor, in July of 1931, Howard writes, “I’ve managed for several years now to get by without grinding at some time-clock punching job. There’s freedom in this game, that’s the main reason I chose it.” Money and freedom, not art, demanded the devotion of the father of sword and sorcery. So, who can say?

A key question, it seems to me, is the social function of the imaginative escapism that Morris and Carter outline. Can simulated escape into elsewhere and elsewhen be seen as possessing prosocial potential? J.R.R. Tolkien seemed to think so. Writing in his famous “On Fairy-Stories,” he asserts the prosocial potential of fantasy escapism:

We need, in any case, to clean our windows; so that the things seen clearly may be freed from the drab blur of triteness or familiarity — from possessiveness. Of all faces those of our familiares are the ones both most difficult to play fantastic tricks with, and most difficult really to see with fresh attention, perceiving their likeness and unlikeness: that they are faces, and yet unique faces.

In other words, escaping into fantasy realms, being winged to the gates of paradise by not-too-importunate tales, restores our ability to see and appreciate difference in others. The real world, over time, hypnotizes us into the blindness of habituation, robs reality of its freshness, transforms it into a black-and-white television display with the volume turned down. Can an anthology of sword and sorcery, like Flashing Swords, like Savage Scrolls, restore our lost vision? Something to aspire to, maybe.

Why did Carter open Flashing Swords 1 with a stanza from Morris’s defense of fantasy? And what is the significance of this decision for the literary history of sword and sorcery? Citing a few more lines from Morris’s poem might help. Morris goes on to relate a tale of sorcery, the story of a wizard who, on a cold winter day, transforms windows into gateways to other realms or sun and warmth:

Folk say, a wizard to a northern king

At Christmas-tide such wondrous things did show,

That through one window men beheld the spring,

And through another saw the summer glow,

And through a third the fruited vines a-row,

While still, unheard, but in its wonted way,

Piped the drear wind of that December day.

Each story, another window; each writer, another wizard; and the winter put to flight. Morris ends his poem in this way: “So with this Earthly Paradise it is, / If ye will read aright, and pardon me.” In other words, this is no fantasy; our situation, here and now, is no different. We, too, can be given glimpses of vibrant life in the midst of Pandemia, of Winter… if we read correctly and reserve judgment. In the end, it is most appropriate Carter began his famous anthology of sword and sorcery with this poem, for it captures the essence of the genre: it is a genre that does not teach. It entertains. Which is another way of saying it brings us to life.

Jason Ray Carney is a Lecturer in Popular Literature at Christopher Newport University. He is the author of the academic book, Weird Tales of Modernity (McFarland), and the fantasy anthology, Rakefire and Other Stories (Pulp Hero Press). He recently edited Savage Scrolls: Thrilling Tales of Sword and Sorcery for Pulp Hero Press and is an editor at The Dark Man: Journal of Robert E. Howard and Pulp Studies and Whetstone: Amateur Magazine of Sword and Sorcery.

This inspires me to dig into poetry! Great post. Love the literary insights.

Thanks for reading it, Seth!

There certainly a place for stories that send a message, but not every story has to have a message. I’ve also seen stories get twisted up trying to show a message particularly political ones. That goes for both left wing and right wing messages.

Agreed!

Jason — most excellent article. Pretty darn thorough. You nailed it!

Thanks, Joe! Eager to start Mad Shadows. I own all three now.

I love the point and counterpoint article, Jason, and I absolutely agree S&S definitely brings us to life and life to us. I’m going to disagree with the declaration “it is a genre that does not teach” however. If Conan always choosing to grab the girl rather than the bag of gems falling over the cliff doesn’t teach he values life more than baubles I can’t think of something better that does. I’d rather say that S&S is a genre that does not preach.

“Does not preach.” I think that’s a really insightful distinction! I also know you’re really invested the heroic in literature, so your point of view makes perfect sense!

“Does not preach.” That’s a really insightful distinction! I also know you’re invested in the heroic in literature, so your point of view makes perfect sense!

Thank you for this, Jason. I really needed to read something like this, at a time when I am struggling with my own writing that attempts to fuse classic fantasy and pulp style with poetry. A lot of doubts have arisen, and I’m sure even more are to come, but reading your take on worth vs joy has been very affirming this morning.

Thanks for reading! Your fusion of pulp style and poetry sounds fascinating.

This was a very refreshing piece to read. Given today’s hyper partisan climate where there seems a social pressure to have every story (fantasy, horror, sci-fi etc.) read like a political treatise, it’s very encouraging to a young amateur like myself to see the roots of fantasy firmly celebrated and to see others acknowledge the Purity of story telling. Great article

Thanks for this comment. I’m glad you enjoyed it! Good luck with your writing!

Jason, this is excellent. Great food for thought. John’s right…you class the place up!

Coincidentally, I’ve just finished reading George Saunders’ new book A Swim in a Pond in the Rain, in which he dissects and discusses five short stories by four 19th-century Russians; he writes this at the end, rather a propos of this descriptive/prescriptive Punch-and-Judy show:

“There’s a certain way of talking about stories that treats them as a kind of salvation, the answer to every problem; they are “what we live by,” and so on…. We shouldn’t overestimate or unduly glorify what fiction does. And actually, we should be wary of insisting that it do anything in particular. The critic Dave Hickey has written about this, the notion that saying what art *should* do might enable a reactionary establishment to start saying what it *must* do, and then to begin silencing those artists whose works aren’t doing that…. And let’s be even more honest: those of us who read and write do it because we love it and because doing it makes us feel more alive…”

He winds up with this splendid insight: “*That’s* what fiction does: it causes an incremental change in the state of a mind. That’s it…. And that’s not nothing. It’s not everything, but it’s not nothing.”

Long quote, but I like what he says.

Thanks for reading this, Dave! Re. “class”: hey, I’ll take it! Haha! The George Saunders’ book you mention sounds great! I’ll have to check that out. The quote is so intriguing. I am 100% in harmony with Hickey (and Jason Waltz above): the art of storytelling can *do* things (i.e. teach), but *demanding* that it do certain things doesn’t have a great history, I dare say. Saunders’ paraphrase of Hickey is perfect: “It’s not everything, but it’s not nothing.” Ha! That resonates with me. Saunders makes me think of what Walter Pater describes as “sleeping before evening,” a tragedy art helps us avoid: “Not to discriminate every moment some passionate attitude in those about us, and in the very brilliancy of their gifts some tragic dividing on their ways, is, on this short day of frost and sun, to sleep before evening.” Yeah, I read to make sure I do not “sleep before evening” (philosophically speaking), and sword and sorcery specifically, because it wakes me up!