A Book Most Extraordinary: Once on a Time by A.A. Milne

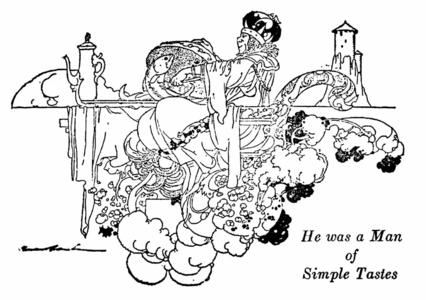

King Merriwig of Euralia sat at breakfast on his castle walls. He lifted the gold cover from the gold dish in front of him, selected a trout and conveyed it carefully to his gold plate. He was a man of simple tastes, but when you have an aunt with the newly acquired gift of turning anything she touches to gold, you must let her practise sometimes. In another age it might have been fretwork.

So begins Once on a Time (1917), A. A. Milne‘s charming and funny fairy tale sendup. In it, a war is started over one king leaping over another king’s land in his seven-league boots, a bad wish is wished (as well as a good one), lovers meet, and a slightly wicked countess plots to steal the kingdom’s wealth. It is a book that had me laughing aloud one minute and forcing my wife to listen to me read pages aloud the next.

Next to the gargantuan, multi-billion-dollar legacy that is Winnie-the-Pooh, it is quite easy to miss that Milne was an author of several adult novels, among them The Red House Mystery, a classic of Golden Age detective fiction. A graduate of Trinity College, Cambridge, he became a columnist for the satirical magazine, Punch, played cricket on teams with P.G. Wodehouse, J.M. Barrie, and Arthur Conan Doyle, and served in the army during WW I. He was wounded at the Somme and spent the last two years of the war writing propaganda. After the war, his son Christopher Robin was born, acquired some stuffed animals, and inspired Milne to write the two books that would be his greatest legacy: Winnie-the-Pooh (1926), and The House at Pooh Corner (1928).

The success of Winnie-the-Pooh was a debilitating thing for Milne and his family. It became an obstacle to Milne’s simply writing what he desired, with his publisher and his audience demanding more in a similar vein. His son came to detest the attention and bullying it brought to him, later writing: “It seemed to me almost that my father had got to where he was by climbing upon my infant shoulders, that he had filched from me my good name and had left me with the empty fame of being his son.”

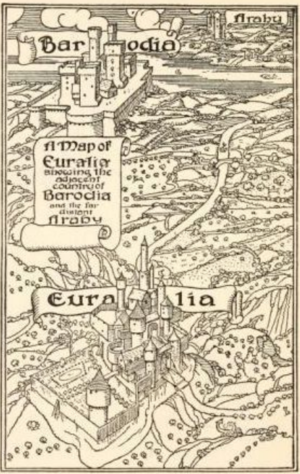

The familial anguish brought about by Milne’s stories about a stuffed bear, though, were in the future when he wrote Once on a Time. In his foreword to the second edition, Milne states he wrote it in 1915 “for the amusement of my wife and myself at a time when life was not very amusing.” The book is filled with silliness, cotton-headed characters, some truly awful poetry, a moment of pure, sublime beauty, and a surfeit of wit. It is presented as the true history of certain events during the Bardo-Euralian War, as well as a critique of an earlier history of the same episode written by one Roger Scurvilegs. Filled with the escapades and trials of an assortment of largely upper-class characters with far less intelligence than they believe, if I was reminded of any other author’s work, it was Milne’s cricket-playing associate, P.G. Wodehouse.

While eating breakfast from his golden dishes and talking to his daughter, Princess Hyacinth, King Merriwig is distressed by the sudden appearance of someone rocketing over his head. A glimpse of his signature ginger whiskers reveals the flyer to be the King of neighboring Barodia. A few loosed arrows and some razored off whiskers later, Euralia and Barodia are at war.

Merriwig leads all the men of Euralia off to war in Barodia, leaving Hyacinth in charge. The most level-headed character in Once on a Time, she is nonetheless unprepared for the chicanery of Countess Belvane. When she realizes she is unable to resist the Countess’ plots, Hyacinth sends for Prince Udo of Araby intending to use him against Belvane. From that invitation spring a series of antics before the world is set to better than right.

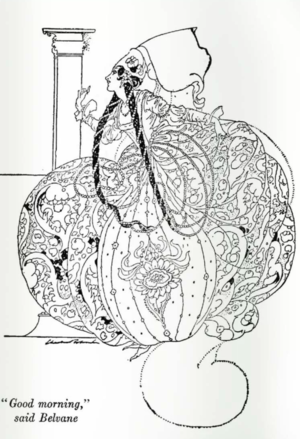

At the heart of Once on a Time is the Countess Belvane and her assorted shenanigans. Inspired by Milne’s wife, Dorothy “Daphne” de Sélincourt, she is a most wonderfully manipulative and ridiculous villain. One after another, she crafts a series of schemes to separate Hyacinth from the contents of the royal treasury. First, there is the Amazon Army, composed solely of a single young girl kitted out with sword and helmet, marched in a near-endless loop between two trees to trick the Princess. Later, Belvane stages the Encouragement of Literature contest which her poems, written under the pseudonym Charlotte Patacake, naturally win. The money she acquires, though, is not for filling her own purse, and she disposes of it almost at once:

Now Roger Scurvilegs would see her go without a pang; he would then turn over to his next chapter, beginning “Meanwhile the King——,” and leave you under the impression that the Countess Belvane was a common thief. I am no such chronicler as that. At all costs I will be fair to my characters.

Belvane, then, had a weakness. She had several of which I have already told you, but this is another one. She had a passion for the distribution of largesse.

I know an old gentleman who plays bowls every evening. He trundles his skip (or whatever he calls it) to one end of the green, toddles after it, and trundles it back again. Think of him for a moment, and then think of Belvane on her cream-white palfrey tossing a bag of gold to right of her and flinging a bag of gold to left of her, as she rides through the cheering crowds; upon my word I think hers is the more admirable exercise.

And, I assure you, no less exacting. When once one has got into this habit of “flinging” or “tossing” money, to give it in any ordinary way, to slide it gently into the palm, is unbearable. Which of us who has, in an heroic moment, flung half a crown to a cabman can ever be content afterwards to hold out a handful of three-penny bits and coppers to him? One must always be flinging. . . .

So it was with Belvane. The largesse habit had got hold of her. It is an expensive habit, but her way of doing it was less expensive than most. The people were taxed to pay for the Amazon Army; the pay of the Amazon Army was flung back at them; could anything be fairer?

Every other character, save Princess Hyacinth, is afflicted with similar humorous tendencies and failings. Both Merriwig and his Barodian counterpart are given to making long disquisitions on things they know nothing about. When they, both hidden from sight under their Cloaks of Darkness, bump into each other, they each convince the other they are veteran swineherds. To gain a good wish, Hyacinth’s lady-in-waiting, Wiggs, must be good an entire day, something she’s never done successfully. The King of Barodia is only short-tempered because that is what the look of his whiskers demanded; by nature, he’s kind and genial. The charming Prince Udo is given to telling excruciatingly dull stories of his excruciatingly dull adventures to any woman who fails to escape his attentions.

Once on a Time, by its title alone indicates a fairy tale setting, which it has, complete with magic swords and cloaks, even magical transformations. But though Milne makes hilarious use of these devices, it is the comical contest of wills and wits between Belvane and Hyacinth that are his greatest concern. The war itself, a comically bloodless undertaking interesting mostly for the way it displays the two opposing kings’ foibles, is a backdrop for the struggle on the homefront between the two women.

As mentioned earlier, Hyacinth is the most intelligent and least self-centered character in the story. Her own acuity notwithstanding, she finds herself unable to take on Belvane. It’s as if she is too sensible to stand a chance against the silliness of Once on a Time‘s world. And Milne spares no effort in making it obvious just how silly a world it is, time and time again.

His comic prose is spot on and never stumbles in its goal of making the reader laugh. A poor dance is described as “a dusty road going up-hill all the way, with nothing but suet pudding waiting for you at the top.” Characters, striving to be polite, regularly expose each other’s ignorance, thus warranting another layer of politeness followed by more comic ignorance. The bad poetry, of which there are numerous examples, all by Countess Belvane, are splendidly bad.

One other fact by way of defence against Roger’s slanders. As judge, Belvane had chosen the subject of the prize poems. Now Belvane and Patacake both excelled in the lighter forms of lyrical verse; yet the subject of the poem was to be epic. “The Barodo-Euralian War”—no less. How many modern writers would be as fair?

“THE BARODO-EURALIAN WAR.”

This line is written in gold, and by itself would obtain a prize in any local competition.

King Merriwig the First rode out to war

As many other kings had done before!

Five hundred men behind him marched to fight—There follows a good deal of scratching out, and then comes (a sudden inspiration) this sublimely simple line:

Left-right, left-right, left-right, left-right, left-right.

One can almost hear the men moving.

What gladsome cheers assailed the balmy air—

They came from north, from south, from everywhere!

No wight that stood upon that sacred scene

Could gaze upon the sight unmoved, I ween:

No wight that stood upon that sacred spot

Could gaze upon the sight unmoved, I wot:It is not quite clear whether the last couplet is an alternative to the couplet before or is purposely added in order to strengthen it. Looking over her left shoulder it seems to me that there is a line drawn through the first one, but I cannot see very clearly because of her hair, which will keep straying over the page.

Why do they march so fearless and so bold?

The answer is not very quickly told.

To put it shortly, the Barodian king

Insulted Merriwig like anything—

King Merriwig, the dignified and wise,

Who saw him flying over with surprise,

As did his daughter, Princess Hyacinth.

Despite all the book’s silliness, it possesses several moments of sublime prettiness. Like when Wiggs, long intending to use her good wish to let her dance like a fairy, gives away her wish to help someone;

Between smiles and tears Wiggs murmured, “He sounds all right. I am g—glad.”

And then she could bear it no longer. She hurried down and out of the Palace—away, away from Udo and the Princess and the Countess and all their talk, to the cool friendly forest, there to be alone and to think over all that she had lost.

It was very quiet in the forest. At the foot of her own favourite tree, a veteran of many hundred summers who stood sentinel over an open glade that dipped to a gurgling brook and climbed gently away from it, she sat down. On the soft green yonder she might have danced, an enchanted place, and now—never, never, never. . . .

How long had she sat there? It must have been a long time—because the forest had been so quiet, and now it was so full of sound. The trees were murmuring something to her, and the birds were singing it, and the brook was trying to tell it too, but it would keep chuckling over the very idea so that you could hardly hear what it was saying, and there were rustlings in the grass—”Get up, get up,” everything was calling to her; “dance, dance.”

She got up, a little frightened. Everything seemed so strangely beautiful. She had never felt it like this before. Yes, she would dance. She must say, “Thank you,” for all this somehow; perhaps they would excuse her if it was not very well expressed.

“This will just be for ‘Thank you'” she said as she got up. “I shall never dance again.”

And then she danced. . . .

Once on a Time is a slight book that should take no more than a day or two of reading to finish. Deeply pleasant and engaging, I found myself charmed while I was reading it, smiling when I put it down, and chuckling whenever I recalled it. If it has any moral lesson it can be summed up thus: be good and be kind. We live in parlous times and charming can go a long way to alleviate the apprehension buffeting us. The book is available from Project Gutenberg complete with Charles Robinson’s gorgeous illustrations.

Sorry to be pedantic, but the title of the novel is Once On a Time, not Once Upon a Time. I have no idea why Milne decided on the truncated phrase. The book, as you say in your excellent review, is absolutely delightful. Milne also wrote a fairy tale called Prince Rabbit, which, in shorter form, sends up contest stories – princes have to complete various tasks to win the hand of the princess and one of the princes is a rabbit. Needless to say, the rabbit succeeds.

Thanks. Sheesh I’m dumb

Prince Rabbit sounds quite fun. I’ve already read The Red House Mystery and am definitely game for his other.

Thanks! Didn’t know these despite being a huge Pooh fan. And I love golden age detective stuff. Once On a Time was free on Kindle, and Project Gutenberg has The Red House Mystery.

I’ve been meaning to re-read Red House myself. Raymond Chandler hated it because it was so ridiculous.