Neverwhens, Where History and Fantasy Collide: Brilliance Gleams Beneath a Black Sun

|

|

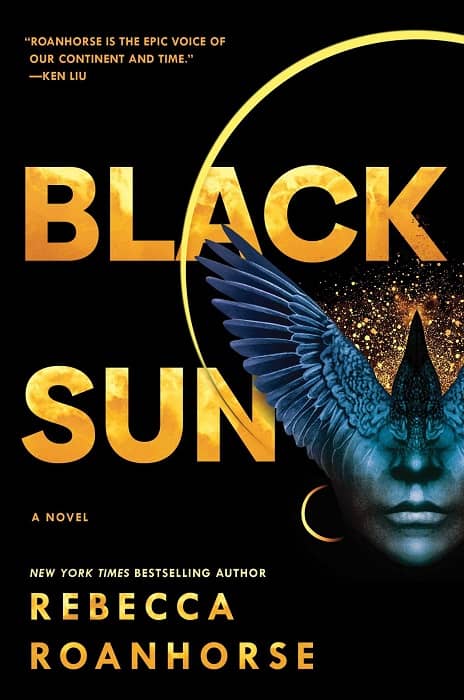

Black Sun by Rebecca Roanhorse (Saga Press, October 2020). Cover by John Picacio.

In the 14 months I have had this column, I’ve looked at “historicity and fantasy” from a variety of angles, one of which has been looking at current — and lauded — works by known authors, and assessing how well they weave the two together. Thus far, I haven’t been very kind. While I loved G. Willow Wilson’s The Bird King as a kind of modern fable, it creates its view of dying Al-Andalus by promoting a series of stereotypes about Christian Spain and the Inquisition that would be excoriated where the same treatment applied to the tale’s Muslim world. Conversely, Guy Gavriel Kay is the master of historical fiction masquerading at fantasy, essentially reinventing the earliest form of “Romantic fiction” with his post-Tigana work. Sadly, in Children of Earth and Sky rather than “jumping the shark,” Kay never gets up to speed, creating a tale that is so faithful to the history it is a thinly-veiled variant of, that nothing much ever happens.

So I thought it was time I praised something in this column — because I generally do like far more than I hate. And wow, what a gem I have to talk about with you today.

Over the winter holidays I read Rebecca Roanhorse’s debut entry into the world of epic fantasy: Black Sun. Billed as Volume 1 of Between Earth and Sky, this is clearly the start of an epic, yet just about works as a standalone tale in its own right.

Published last year, this is a departure for Roanhorse, whose work has mostly been contemporary fantasy, though again drawing on native themes. So what’s it about? Well, our official blurb actually does a pretty good job of teasing the plot. Here it is.

A god will return

When the earth and sky converge

Under the black sunIn the holy city of Tova, the winter solstice is usually a time for celebration and renewal, but this year it coincides with a solar eclipse, a rare celestial event proscribed by the Sun Priest as an unbalancing of the world.

Meanwhile, a ship launches from a distant city bound for Tova and set to arrive on the solstice. The captain of the ship, Xiala, is a disgraced Teek whose song can calm the waters around her as easily as it can warp a man’s mind. Her ship carries one passenger. Described as harmless, the passenger, Serapio, is a young man, blind, scarred, and cloaked in destiny. As Xiala well knows, when a man is described as harmless, he usually ends up being a villain.

There are so many things to love about this novel, but this is Neverwhens, so let’s start with the setting. This is not “Earth”, not even a parallel Earth, but it IS a fantastic secondary world closely based on the cultures, myths and traditions of North America. There are no golden-haired raiders, steel-clad knights with even steelier grey eyes, anymore than there are silken Mandarins or feudal daimyo — Europe and East Asia being the “go to” spots for fantasy. (I know it is vogue to tout all of the Asian fantasy available now, but what’s new is the amount in translation and the number of Asian *writers* — as a destination or inspiration, Asian settings, myths, history and themes has been used since at least the late 19th century.)

Roanhorse doesn’t need any of those places for inspiration. North America was also home to great civilizations and city builders — not just the vast stone cities of Mesoamerica (well represented here), but also the Mississippian Mound-Builders, whose great city of Cahokia here in Illinois was nearly the size of Paris at the same time in the 12th century, and the mysterious, still little understood towns, villages, and “great houses” of the Ancestral Pueblo (if you are over 40 you probably know them as the “Anasazi”, but seeing as that is a Navajo name meaning “ancient enemies”, the term has fallen from favor), who built extensive road networks throughout the American southwest and who were certainly trading deep into Mexico and east to the Mississippi.

All of these cultures are represented in various ways and to varying degrees in Black Sun — some on stage, some hinted at and likely to be revealed in later tales — but in a way that is unique and cohesive to the world Roanhorse wants you to experience. Some of the places in this book are fantasy versions of the Americas as they were, some as they might have been and some as they could have become had European colonization never occurred. There are reviewers on Goodreads, who want to let people know that XYZ culture isn’t “really” Mayan or Pueblo or Navajo, etc. That is why this is called a *Secondary World*. Tolkien’s Rohirrim were not Anglo-Saxons, even though they were inspired by them, Martin’s Dothraki are not Mongols. Part of what I like about this novel is that Roanhorse, herself Native American, isn’t afraid to use these cultures as *inspiration* to create something new. Yes, the southern Crescent Sea cities are very Mayan, though with human sacrifice now excised by the religious elite to the north, and *that* city of Tova feels very much in line with the legends of the Ancestral Puebloans and great city builders of the southwest, while the warrior folk in distant Hokaia, located along the banks of a great river hints at the great North American metropolis of Cahokia. Likewise, the languages are based on Yucatec Mayan and Teha, but there is mixing and matching, elements of her own imagination, and it all blends into something wonderful and original.

(I mean, we can also have Polynesian-Amazon-dolphin shapeshifters? Yes, please!)

Best of all, it is clear enough in the author’s mind that she can relate it on the page by *showing* not telling. This is a very quick-moving story and Roanhorse’s prose is strong, clear but also crisp — she uses just enough description to create imagery but lets the character’s words, thoughts and actions bring her story to life.

“Today he would become a god.”

That is the first line of the novel, and it sucks you in to the world. The prologue that follows, a painful to read scene in which a mother willfully maims her child as part of a religious ritual to make him more than human, sucks you in, makes you struggle with your values versus this world’s, then shows that even within this setting, all is not a simple answer of religious right and wrong — with virtually no exposition, all just shown through the experiences of the adolescent and the dialogue of the adults he hears. With this we meet Serapio, the first, and *perhaps* most important of our narrative characters, and the brilliance of his tale is how much we can identify with, sympathize with, even root for, a character who believes he is the avatar of the avenging Crow God, on a mission of destruction.

But this tale is not just Serapio’s and he represents only one view of what is happening in the holy city of Tova, and its ruling religious caste. There are four main view point characters and each is clearly distinct from the others in thoughts, “voice”, motives and behavior. After the epic backstory of Serapio we jump to Xiala, sailor, and member of a mysterious sea-faring people who supposedly kill their men folk, and calm the seas by singing. Xiala is in prison sleeping off a drunken misadventure (and the bedding of a powerful man’s wife), when a powerful and mysterious lord (who may or may not be a sorcerer) arranges her freedom in return for a job: deliver an important cargo to reach holy city Tova less than a month — specifically, before an upcoming eclipse. Of course, Serapio is the cargo, and the eclipse — when the Sun God who has banished Crow is at his weakest — is crucial to the plans of those who chafe under the Sun Priests’ yoke.

It’s a story that is almost a slice of noir fiction, but tied to high fantasy, in a uniquely North American world. Serapio and Xiala are fantastic characters, their journey exciting, but it is only half the tale — we also meet Nara, the first of the Sun Priests, despite her rise to power from humble origins, and Okoa, a warrior of the distrusted, yet still powerful Crow clan. All of these characters have origins that involve fraught relationships, broken homes, failed romance — things that every modern person can understand, despite the fact that the four characters are all very much people of this unique world. Best of all, you find each interesting, engaging and you are rooting for them — even when the objectives of two are directly opposed. There are straight, bi and trans characters and their identities, and the implications of the same, are woven into the culture — again, it isn’t simply a matter of including twin-souled or bisexual characters to show “representation” by the straight, cis-author, but to show how those people and their identities are part of the cultures of this world.

It has been an exciting time in fantasy fiction on the one hand with the explosion of Africa, Middle Eastern and East Asian settings; and as someone with a deep love for the great civilizations of Meso and South America, I certainly hope this may herald a similar treatment for the “New World.” But there here has also been an unfortunate side effect to the push for more representation, especially with OwnVoices, and that has been an unintended “ghettoizing” of authors: increasingly, Asian authors only write Asian settings, White authors only write White settings, etc., and fret over borrowing from outside their sources, lest they here the cry “Appropriation”. There’s a very long line between drawing “inspiration” and “appropriation” in art, however, and part of dispersing with racial stereotyping is not assuming that our race makes us qualified or unqualified to write about anything connected to that race. North America is a vast land with hundreds of indigenous cultures, even more that are sadly extinct, or whose survivors are far removed from their pre-contact ancestry. It was refreshing and very intellectually honest to see Roanhorse discuss in her afterward the research it took for her to learn about Mesoamerica and Cahokia, and her willingness to note that her world has a dash of Polynesia and the Roman criminal underworld for good measure.

And why shouldn’t it? Giant insects and riding crows weren’t part of pre-contact America, either — this is where the beauty of secondary world building comes alive: we can celebrate the cultural touchstones of the world she is creating, and the authenticity it gives to her world, and then equally enjoy the small changes and “parallel evolutions” she introduces to make the world new, fresh and her own.

This is a strong fantasy and the opening of a trilogy that I hope will show the potential of heroic fantasy inspired by the Americas. You should read it and travel someplace new.