Lin Carter’s Imaginary Worlds #2 World Building and Naming

|

|

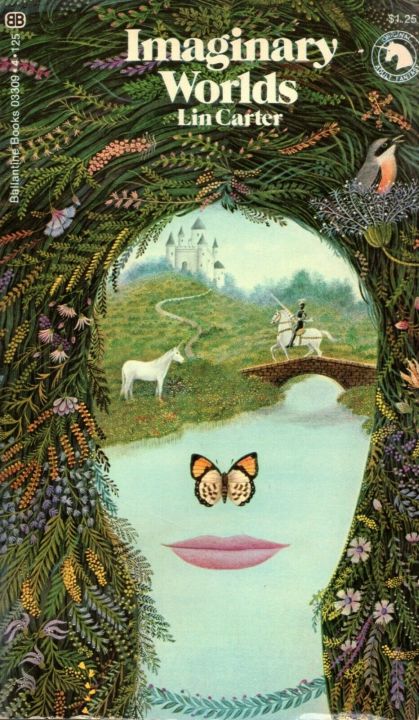

Imaginary Worlds (Ballantine Books, June 1973). Cover by Gervasio Gallardo

So I had great fun reading Carter’s snarky, anecdotal, history of the Fantasy genre, Imaginary Worlds (1973), but I had actually come to the book for his thoughts on writing the Fantasy, and in particular Sword and Sorcery.

In hindsight, perhaps this was more of by way of exorcism.

Carter was adamant that Sword and Sorcery should have no content whatsoever: “It is a tradition that aspires to do little more than entertain and stretch the imagination a little.“

We can certainly agree that Sword and Sorcery doesn’t handle topical themes well. The clue is in the name. Though I myself know many people with swords on their wall and grimoires on their shelves, I will admit that I am not entirely typical in this regard. The secondary worlds of the Sacred Genre are too far removed from modernity to explore it directly.

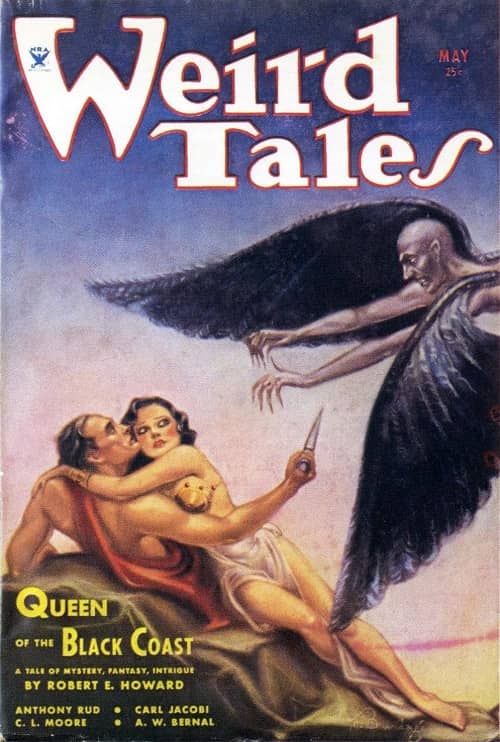

Howard’s Queen of the Black Coast in Weird Tales, May 1934. Cover by Margaret Brundage

What Carter does not seem to have noticed is that Sword and Sorcery is very well equipped to tackle deeper less transitory themes around — so help me Crom — e.g. epistemology and existentialism:

Let teachers and philosophers brood over questions of reality and illusion. I know this: if life is illusion, then I am no less an illusion, and being thus, the illusion is real to me. I live, I burn with life, I love, I slay, and am content.”

That’s Howard’s Conan in Queen of the Black Coast, a story expanded-by-pastiche by Carter himself, so he has no excuse. I have no idea what was wrong with him! (Answers in comments, please!)

However, it turns out that because Carter preserves an ironic distance from his stories — not channelling the way Howard did Conan — it allows him to more readily see them from the reader’s point of view, meaning he has some useful observations.

Fantasy, says Carter, has unique technical problems. Thriller writers, for example, can reference real-world entities that readers already believe in. The Fantasy author, however, must make the unreal seem real:

Each of these exotic elements — dragon, sword, magician — must somehow be made to seem real to the reader… This is far more difficult than it may first sound.

Why create your own world when it’s easier to get buy-in if you borrow from mythology?

Because the milieu of — say — The Nibelunglied is “most suitable for retelling the Seigfried epic”, less so for a new story, and also requires extensive research, a time sink that also limits the author’s imagination. Newly invented worlds give much greater “freedom of scenery and locale”, and thus storytelling.

What does an invented world comprise of?

1. Invented Geography, which you shouldn’t mess up.

The fantasy author should do everything possible to convince his reader that his invented world is real and genuine.

So, don’t park your jungle next to your tundra, and have your cities exist for a reason — he provides a one-page summary of how to do that.

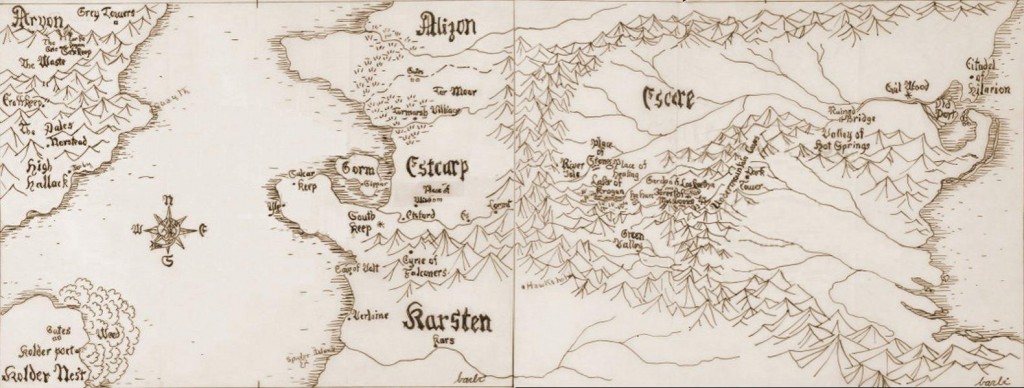

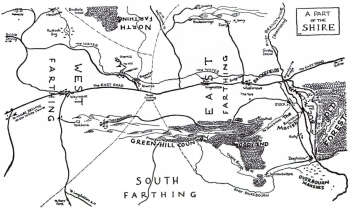

Have a map, he says, so you don’t mess up when describing your hero’s journeys. A ninja hack is to grab a bit of a real map and use that as a guide to climate and fauna.

2. Invented Politics, meaning you should have a sense of how historical prototypes work and design accordingly. He treats us to a whistlestop tour of the Roman Empire, Feudalism, post-medieval Germany…

I think I would very much have liked to have had a drink with Lin Carter, several, but I’m in my 50s and have had decades to read about history. I can imagine this casual erudition terrifying a younger aspiring author; really I think it’s OK to riff off just one milieu, and perhaps read Machiavelli’s The Prince to have a sense of how powerful people do things. (The 48 Laws of Power is also good.)

Do not, he implies, go heavy on info dumps:

…an author should know a lot more about [their fantasy world] than he sets down in his story.

3. A Culture. Yes, Carter is a great fan of Howard’s invented epigraphs:

“Know, oh prince, that between the years when the oceans drank Atlantis and the gleaming cities, and the years of the rise of the Sons of Aryas, there was an Age undreamed of, when shining kingdoms lay spread across the world like blue mantles beneath the stars.”

But it is a point well made. Believable secondary worlds have their legends and lore, and popular entertainment.

4. “An offstage diverse world”, for verisimilitude. He says travelogues are OK if you must, but a good shortcut is to reference other places when describing artefacts and people.

…rubies from old Pythuntus… a lounger in a faded Stryphax kilt.

I think this technique became something of a cliche, and overusing it can result in a book becoming disorientating. However, it still has its place and its one thing that gives the Historical fiction of Harold Lamb such a sense of place.

5. “A local habitation and a name”, which Carter deems worthy of a chapter of its own. He calls the practice of making up Fantasy names, Neocognomina and admits to being “a fanatic on the topic”.

He recommends having a pre-prepared list of names you can tap when you need them. Do not, he says, fall into the trap of — I paraphrase — spawning random **** with too many X’s, Z’s and Q’s. Nor should you fall back on tweaking historical names — welcome to um Constantibyzantium!

Cue two… no three… pages of Carter ripping into Howard, Jakes, Leigh Brackett and even the mighty Michael Moorcock! (Oh how he must have laughed as he typed these passages.)

How then are we to make up fantasy names?

First, we must go for aptness. He cites Edgar Rice Burroughs having “ersite”, a type of stone, and “giant pimalia” a kind of flower. Cue another page of entertaining rant.

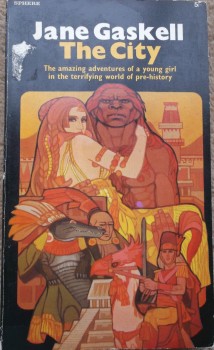

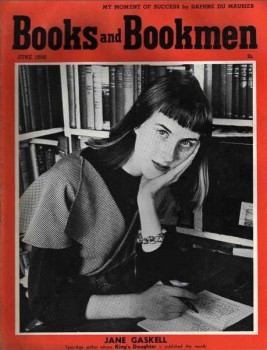

He quotes CS Lewis writing to Jane Gaskell:

[Fantasy names] ought to be beautiful and suggestive as well as strange; not merely odd.

He follows with yet more illustrative ranting, beating on Moorcock again, then amusingly asserts with respect to his own Sword and Sorcery hero:

“Thongor” has a grim weight to it, solidity and the ring of clashing steel.

Um.

That last is odd, because — as a part-time Norman friend of mine pointed out — despite having told us not to riff off real names:

…needing a name for a wealthy and fabulous metropolis, I coined the “Palmyrium”. The name derived from an extinct nation of the Near East called Palmyra…

It’s also unclear how names can be resonant if people haven’t heard of the original.

Overall, Carter isn’t really consistent in what examples he likes and dislikes. Nevertheless, it seems to me he’s right in that, that no matter how simulated ground-up our world is, the names we coin have a literary effect of their own.

Carter very much approves of creating your language; not going full Tolkien, but at least being like Edgar Rice Burroughs and having a lexicon of relevant titles like “jed” and “jeddak” for king and emperor. The important thing is that “work out these terms in advance”.

He also thinks you should avoid things that feel like anachronisms. For example, unless you want to imply a modern army, don’t have “battalions”, “goose-stepping” and an “H.Q.” Do, instead, pick words that reference an appropriate milieu. “Legions and hosts”, are your friend.

He closes the chapter with some sound advice on building up your lexicon. Spread your names out over the alphabet to avoid confusion. Only use unpronounceable names if you have a literary reason for it, for example “Cthulhu” is supposed to be an alien entity with an alien name. Theme your names, for example by region, partly to signpost the world in the reader’s head, but also to convey emotional nuance. He praises Tolkien for using homely names for homely places, and borrowing old English prefixes for the shire, but also lambasts him for having too many names ending in “-or”, implying everybody speaks the same language.

Pick names that sound like names, he urges, and don’t lean to heavily on T and S… cue another rant.

Finally, we come to his promising chapter on The Tricks of the Trade, but that is for my final article in this series.

M Harold Page is the sword-swinging author of Swords Versus Tanks. Go take a look at his latest novel, The Flying Tooth Garden Volume 1: The Jungle Tomb of the Ice Queen (A Reincarnation LitRPG)!

Many of Carter’s judgments are highly debatable, to say the least, and some of his swipes at particular authors and books raise my hackles (I LIKE Silas Marner), but if you want to read a REALLY snarky book on the genre, dig up a copy of Wizardry and Wild Romance by Michael Moorcock and (an uncredited) James Cawthorne. It makes Carter look like a model of decorum.

They are great fun, though.

‘It’s also unclear how names can be resonant if people haven’t heard the original.’

This. I think this might be what makes the fantasy genre as a whole so challenging (and what Carter seems to have played down or ignored) – what’s true of names should be true of the world as a whole: its resonance is predicated on evoking certain existing associations in the reader’s mind, but deploying them in a refreshing and unfamiliar way.

The Narnian books are a good example. A wardrobe, a container for clothes, is a container for a world. A lamp – something the reader would associate with a busy city – stands in the middle of a snowy wood. A faun – a creature normally associated with classical mythology and southern climes – lives in that same snowy wood.*

Tolkien takes dragons, elves and dwarves and actually has them inhabit a minutely detailed world of their own, and he has this world described from the perspective of a character who isn’t so very different from the reader. In this respect, The Hobbit is more like a portal fantasy than anything else. We identify with Bilbo and Bilbo’s longing to see real live dragons and dwarves and wizards; the difference is that Bilbo only has to leave his home to encounter these things.

It’s also one reason why the fantasy genre is a genre of steadily diminishing returns; people recycle the same tropes again and again, to ever dwindling effect.

I should add that another factor (re the law of diminishing returns) is that most of the characters, locations and situations you draw on should have some basis in existing mythologies, even if that association is nothing more than the type of weaponry used. Maybe this is why Tolkien and Lewis have never been equalled when it comes to world-building? Tolkien uses pretty much everything associated with Northern European mythology while Lewis taps into Classical mythology. What’s left?

Sword & Sorcery pretty much does what it says on the tin in terms of world-building. That’s its greatest strength and its greatest limitation. There are swords and there are sorcerers. The guys with the swords are good; the guys who are sorcerers are bad. On one level you have more latitude. Your world doesn’t need to be particularly well-constructed as long as you have both of the above. On another, it’s more restrictive because it’s hard to be inventive or original within such narrow parameters. In that respect it suffers from much the same problem; has anybody added anything new to the genre since its heyday? Moorcock maybe (and only because – or so I suspect – his tongue was firmly in his cheek).

I am really enjoying this series Harold and will keep an eye out for imaginary Worlds when scanning the shelves of second hand bookshops. Haven’t read much Carter myself, outside the Conan pastiches. Oddly enough my first encounter with Thongor, that i can recall, was at the hands of a pastiche by Robert Price, Witch Queen of Lemuria (Rainfall Chapbook).

In terms of the basis in mythology argument, I think it really comes down to when a specific fantasy was written and the expectations of the public. As fantasy has progressed and become more mainstream, the suspension of disbelief – a term borrowed from role playing – has become easier and hence the need to ground the world on something recognizably earth like less of a requirement.

I had a bit of a laugh at the fantasy names. As many a FRP player or games master will have experienced, it can become something with a life of its own, that of making up names. The running joke when i GM is “no more names starting with B”

As for writing, i do believe that names can in their own way help define cultures. So mixing up the sound of names can potentially be jarring. “Vasili {Russian} and his sister Ethnea {Celtic} could be hard to pass off. Whereas if a specific sound name is linked to a place or culture and later on another character with a similar name come along, chances are the reader will naturally assume said newcomer is from the same established culture. Well, that’s my take on it, having never had a story published would be interesting to hear what others have to say.