Alien Eggs, a Diligent Salesman, and a Robot Psychiatrist: Three Stories by Idris Seabright

|

|

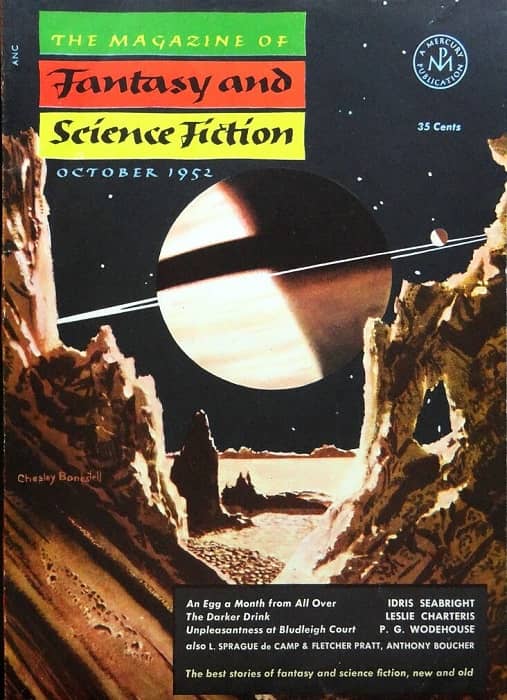

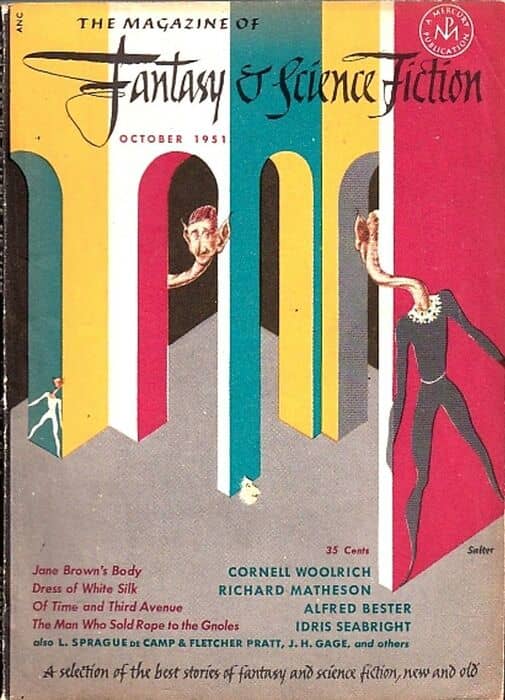

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, October 1952. Cover art by Chesley Bonestell

For my next look at older stories which I think are both good, and worth looking at closely, I’m covering three stories by one “Idris Seabright.” “Who she?” you might ask, or even “Who he?,” as the currently most famous Idris in the world is a man. “Idris Seabright” was a pseudonym used by the SF writer Margaret St. Clair for about 20 stories, all in the ‘50s. The “Seabright” name was used almost exclusively for stories published in F&SF – the single exception is one of her most famous stories, “Short in the Chest,” which appeared in Fantastic Universe. (The ISFDB credits a curious Seabright outlier, a story published in Spanish only, very late in St. Clair’s life, in 1991. I feel this must be a translation of an earlier Seabright story though I’m not sure which one. The story is called “La Estrana Tienda,” which means “The Strange Store” or perhaps “The Mysterious Shop.”)

Margaret St. Clair (1911-1995) was one of the more noticeable early women writers of SF, but somehow her profile was a bit lower than those of C. L. Moore, Leigh Brackett, and Andre Norton. I guess I’d say that those writers did just a bit more, and were just a bit better (taken as a whole) than her, but it does seem that she’s not quite as well remembered as perhaps she deserves. One contributing factor is probably, however, that many of her best and most interesting stories were as by “Idris Seabright.” In addition, those of her novels I’ve read were less successful than her short fiction. Her career in SF stretched from 1946 to 1981. Her husband, Eric St. Clair, was also a writer (of children’s books), and the two became Wiccans more or less when the Wiccan movement started.

[Click the images for larger versions.]

St. Clair published some very enjoyable stories under her own name. In general, the “St. Clair” stories were more likely to be Science Fiction, and were also usually a bit more traditional in structure, and more likely to hew to what might be called “pulp” conventions and themes. The “Seabright” stories were far more idiosyncratic. (I note, by the way, that a quite enjoyable early story by St. Clair, “The Sacred Martian Pig,” a rather pulpy romp that I thought good fun, was retitled “Idris’ Pig” when she collected it in 1964. I suspect the new title was a cute reference to her pseudonym.) In this piece I take a closer look at three of the most famous “Idris Seabright” stories. As ever with these essays, which are attempting to understand how stories, work, there will be spoilers. And these three pieces are all quite short, so it’s hard to say much at all without revealing what’s going on.

|

|

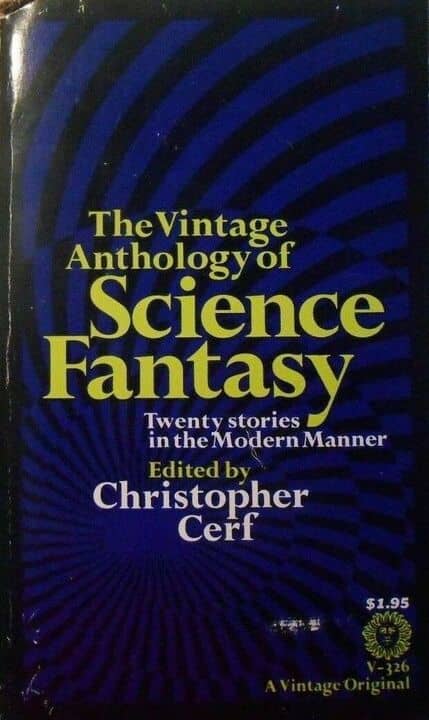

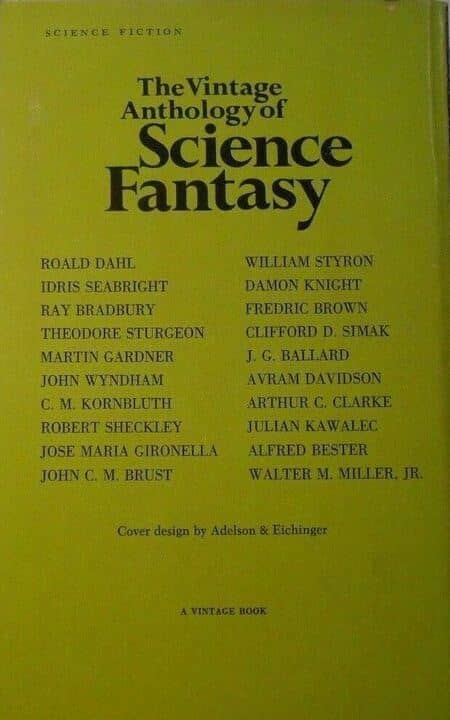

The Vintage Anthology of Science Fantasy (Vintage Books, 1966). Cover by Adelson & Eichinger

- “An Egg a Month from All Over” (F&SF, October 1952)

I read this story a very long time ago, in one of the first SF anthologies I ever owned, The Vintage Anthology of Science Fantasy, edited by Christopher Cerf. (Cerf was the son of Bennet Cerf, who co-founded the legendary publisher Random House. Vintage was one of the paperback imprints of Random House.) I was probably about 12 or 13 when I got this book, and I really think it’s a spectacular anthology – including stories like Theodore Sturgeon’s “And Now the News …,” Ray Bradbury’s “There Will Come Soft Rains,” J. G. Ballard’s “Chronopolis,” Alfred Bester’s “The Men Who Murdered Mohammed,” Damon Knight’s “The Analogues,” Avram Davidson’s “Or All the Seas With Oysters,” and Walter M. Miller’s “A Canticle for Leibowitz.”

It also had stories from non-genre writers like William Styron, Jose Maria Gironella, Roald Dahl, John C. M. Brust, and Martin Gardner. Its one weakness (not unusual in 1966 when it appeared) was that it had only one story by a woman – “An Egg a Month from All Over.” I really think this was a tremendous early introduction to short SF for me.

“An Egg a Month from All Over” has been anthologized only a few times, surprisingly: in The Best of Margeret St. Clair, in an early Judith Merril anthology called Human?, in the Cerf anthology I’ve mentioned, and in a very popular Isaac Asimov/Groff Conklin book called Fifty Great Short Science Fiction Tales, a collection of SF short-shorts that I also read at a very young age.

“An Egg a Month from All Over” concerns one George Lidders, a 46 year old man who lived with his mother his whole life until her death – so he’s a confirmed bachelor, and his major avocation is his membership in the Egg-of-the-Month club, via which he gets an alien egg each month, with instructions on how to care for it until it hatches. But right at the start we are shown the egg collector mistaking a mnxx egg for a chu lizard … Lidders receives the egg, and happily follows the directions on how to hatch a chu lizard. To no one’s particular surprise, things don’t go well when the mnxx bird hatches instead!

So far, so fairly normal an SF horror story. What lifts this one above the rest? – and I do think it is a particularly good short humorous SF horror story. It’s the details, of course, most of which I’ve omitted. (Read the story!) Some of it is the characterization of Lidders, though in all honesty there’s nothing that much new there (I mean, Faulkner did it better in “A Rose for Emily,” right?) Still, very well done.

Also, there is the back story of the mnxx egg, and why it was mistaken for a chu lizard egg. That’s really delightful – it seems it was all part of a plot by one alien to revenge himself on another … a plot foiled before the egg collector ever showed up. Seabright cleverly brings this up briefly once or twice more as the story goes on. Nicely done. Another great part is the description of the mnxx bird. This aspect is completely original, very striking, and quite horrific. And it’s not over at the end of the story…

|

|

The Magazine of Fantasy & Science Fiction, October 1951. Cover art by George Salter

- “The Man Who Sold Rope to the Gnoles” (F&SF, October 1951)

This story is interesting in part because it is derived, to a degree, from a story by Lord Dunsany, “How Nuth Would Have Practiced his Art Upon the Gnoles.” Dunsany’s story describes a group of people? (or creatures?) who live in curious trees, and who are very jealous of their treasure, and who are very hard to steal from. The great burglar Nuth makes an attempt … but is wise enough to send an apprentice instead. (With sad results for the apprentice.)

Seabright’s story clearly intends for the gnoles to be Dunsany’s creatures, but she quite nicely elaborates on their nature. (They were really not described at all in the Dunsany story.) An ambitious young rope salesman named Mortenson learns that the gnoles are in need of rope. He has just the thing! And he has a manual describing the proper way to make a sale! Unfortunately, while he read the parts in the manual about “dogged persistence” and “unfailing courtesy” he didn’t pay enough attention to “tact and keen powers of observation.” Mortenson visits the gnoles, and offers them his various samples of rope – very high quality indeed. And they offer him a precious emerald in payment. But Mortenson thinks to take something else instead. This too has sad results.

(“Gnoles” were later – some say – used by Gary Gygax in creating the creatures called “gnolls” in Dungeons and Dragons. I have to say, though, that Gygax’s “gnolls” don’t seem to me to resemble either Dunsany or Seabright’s “gnoles” very much at all.)

What makes this story special? Again, it’s the details. To begin with, there’s the delightful description of Mortenson’s training manual. And then the description of the gnoles’ place of residence, a strange tree (clearly derived from Dunsany, but well elaborated), and of their physical characteristics … “a little like a Jerusalem artichoke made of India rubber,” looking like an anteater, eyes like gems, no ears. Mortenson’s eagerness to make the sale – and his actually ethical, but misguided, decision to refuse the emeralds and take something else – is excellently portrayed, and his final fate, and the way it is described as somewhat merciful, is perfect.

|

|

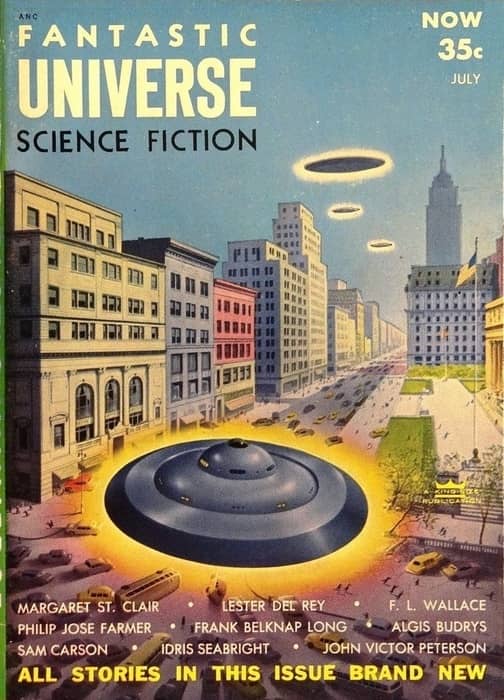

Fantastic Universe, July 1954. Cover art by Alex Schomburg

- “Short in the Chest” (Fantastic Universe, July 1954)

“Short in the Chest” is one of Margaret St. Clair’s best-known stories, and it is the ONLY “Idris Seabright” story that didn’t first appear in F&SF. I imagine perhaps they were offered it, and in that case I don’t know why they rejected it. Alternatively, it may have been written as a St. Clair story and submitted as such to Fantastic Universe, and they may have asked to use the “Seabright” name because the same issue includes another St. Clair story, “The Regions of Tantalus.”

This story is set in the fairly near future. There is constant conflict between the US and its rivals such as the Soviet Union, so much so that it seems like much of the population is in the military, in such services as Air or Marine. And for general morale, it is required that members of each service regularly “dight” (have sex) with members of another service. The story concerns the visit of a girl (so described) to a “huxley” – a robot psychiatrist.

The girl is from the Marine service, and she discusses her unfortunate recent liaison with a man from Air; and the fact that despite the “Watson” she took (I assume the allusion is to James Watson?) she simply couldn’t enjoy it, and neither did he. What could be going wrong, she wonders – but with the huxley’s help, she realizes it’s because Marines naturally hate Air. (What is going on with this unhelpful huxley? Could it be the short in its chest?)

Baldly, this seems like a very basic story of interservice rivalry. But by the end we realize the result of the huxley’s maneuvering will be horrible interservice fighting. As such, perhaps it’s just a satire on the rivalry between both sides in the Cold War – and how that might lead to the Cold War becoming an internal war. But there’s something else going on – something about “dighting,” and about forced sex, and about robots. I’m not sure I’m fully aware of what Seabright was up to here, but I know the story is disquieting, and quite memorable.

To summarize – what made “Idris Seabright” different from Margaret St. Clair? At one level it could have been as simple as a persona she took on to cater to the F&SF market. But I think there’s more going on. The “Idris Seabright” stories are just plain weirder than most of the St. Clair stories. (Though stories published as by St. Clair such as “Horror Howce” and “Roberta” are in themselves plenty weird enough!) As Seabright, St. Clair was slyly funny, and often, behind the humor, pretty scary. Margaret St. Clair is in general worth a wide rediscovery, I think, and her “Idris Seabright” stories are especially good.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was a review of The Gentleman by Forrest Leo. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

I’m happy to see any mention of St. Clair; she deserves to be better remembered. She wrote one of my very favorite pulp sf novels, Agent of the Unknown, a story that shows surprising depth of feeling for something that appeared as half of an Ace Double.

Not pulp, but otherwise yes.

So what’s pulp SF then? I’ve always considered St. Clair pulp as well (at least what I’ve read so far).

The most technical definition, that Todd (and I) tend to adhere to is that “Pulp” is what appeared in “Pulp magazines”, which is to say magazines that were printed on pulp paper, and usually in the larger size you see in old pulp magazines (typically 7″ by 10″, but not always). This was the format for all SF magazines from 1926 until about 1942, when Astounding switched to digest. (Todd will correct me if I missed something> ) There were pulp magazines before that, of course — the great adventure fiction magazines, things like Argosy and Blue Book, were pulps. The format ended in SF mostly by 1955 — I think a couple of issues of Science Fiction Quarterly may have been pulp format for a year or two after that. I think some Romance pulps may have lingered a bit longer, and I believe a Western pulp survived into the late ’60s.

In this sense St. Clair was a “pulp” writer, as she had early stories in pulps like Thrilling Wonder Stories. Agent of the Unknown, however, appeared as part of an Ace Double, technically not a pulp.

It’s true, however, that many people apply the term more widely to, say, all genre magazines at least through the 1950s; and also to the paperbacks that appeared beginning in about 1940 but which became more common (and more likely to have sensational covers) in the early 1950s. In that sense Agent of the Unknown would qualify.

It’s also true that many people use it as a quality designator, but that’s subjective, and for example people might call some of the classic early paperbacks “pulp fiction” when sometimes they were very highbrow novels with sensational covers (and blurbs) slapped on. Likewise, true pulps like, say, Thrilling Wonder published some outstanding and not very “pulpy” fiction in among the thud and blunder.

Another sf writer whose work I should know better, try as I can to squeeze her in when I find used copies of her work. And I too like her short works better than her longer ones, though The Dolphins of Altair works for me, cetacean fan that I am.

Alas, Ms. St. Clair may best be known not for her writing but for what was written on one of her books. The back cover text for Sign of the Labrys is an infamous blurb: “Women Are Writing Science Fiction!”, which uses a welter of exclamation points to lavish us with the idea of how women are “closer to the primitive than men”, so “They are conscious of the moon-pulls, the earth-tides. They possess a buried memory of humankind’s obscure and ancient past which can emerge to uniquely color and flavor a novel.” Or a casserole if not a novel? Oy.

Damn! I thought I was the only one to possess a buried memory of humankind’s obscure and ancient past. Now I’ll have to change my Facebook profile.

I recently discovered Seabright in “Beyond Human Ken”, an anthology of short stories from 1952. the book is literally crumbling away as I read it. In my 50 years of science fiction reading I had never seen any of her stories. Now I am actively looking for them. And avoiding the gnoles.

I’d certainly dispute the notion that she Isn’t Quite Up to even Brackett, much less Norton. Even her most “conventional” work, such as the Oona and Jick stories in THRILLING WONDER STORIES in the ’40s, are slyly challenging the perceptions of the reader. I’ll admit, I haven’t read her novels yet…but I certainly don’t value novels over shorter work, particularly given how so many of the novels in fantastic fiction have had to be published, particularly in the 1950s-70s…”St. Clair” was apparently a (I assume legally) adopted name of her husband’s and probably of both of them together…as with Lester Del Rey, “Anthony Boucher “and others, a lot of hiding games going on…

I think we’ve discussed this before … I will agree that part of my reason for ranking St. Clair lower is that those novels of hers that I’ve read are severely flawed (though not without interest.) (These are THE GREEN QUEEN, THE GAMES OF NEITH, and MESSAGE FROM THE EOCENE.) The SFE plumps for AGENT OF THE UNKOWN as possibly her best, or at least most interesting — I shall have to try to find it, though its status as half of an Ace Double with a Philip K. Dick novel has led, in the past, to elevated prices.

I still think I have to rate Brackett more highly — one of my true favorites, supremely enjoyable, and capable as well of “slyly challenging” fiction, especially in, say, “The Queer Ones”. (Or her other Venture story, “All the Colors of the Rainbow, a bit more overt and messagy (indeed downright preachy), but still effective.)

I would agree, and I trust I’ve never said otherwise, that Norton, book by book, line by line, was the lesser writer. Norton’s impact lay partly in her consistent and prolific output, partly in her influence as a YA writer. By sheer volume of output, and by her effect on young readers, she was I think reasonably regarded as “more important” than many other significantly better writers.

Bottom line is — good as St. Clair was, I don’t think she was a severely neglected “Grand Master” candidate, and even if we give C. L. Moore credit (as we should) for truly being a “Grand Master”, I’d still say that Norton deserved it; and that Brackett should have got it (probably died just a bit too soon), and that the snubs to, say, Carol Emshwiller and Kate Wilhelm concern me more that St. Clair.

Oh, I’d say that St. Clair deserves more credit than she gets, and I won’t say that she’s better than Brackett at Brackett’s best, but they are on par for me (as a not-yet reader of MSC’s novels). As much of St. Clair’s work was fantasy, I think the GM status would be kept out of her grasp for that reason and her relative lack of work past the ’60s (as the one credential would work against her with some eligible voters and the other with others), and indeed the lack of interest in re” the likes of Emshwiller (John Scalzi being one of the skeptics with clout in this regard?) and Wilhelm is even more blatantly a disservice to both the writers and SFWA. I definitely took your “looking at the work as a whole” phrase as being divided between each writer…Norton at her best didn’t touch St. Clair at hers…so I’m glad you meant the works of all three taken as a whole. (Importance does drag in a lot of somewhat problematic writers, such as M. L’Engle.) Yes, these snubs you cite, and the Writer Emeritus nonsense, are definitely blots on the record.

Also, I did not know that bit about the “St. Clair” name being a legally adopted pseudonym of either Eric or both of them. Interesting! (Neither the SFE nor Wikipedia reports that information, and they were my main sources. (Yes, bad me!))

Also, Rich, note that St. Clair has two stories in that FANTASTIC UNIVERSE issue…tagging one as “Seabright” might simply be following standard practice in most magazines in those years…though it is interesting that the more generally well-regarded story is the one she attributed to “Seabright” (unless it was done without her consent, or editor Hans Stefan Santesson was uncertain as to which was supposed to be which).

Just noting that I brought up the possibility that the reason “Short in the Chest” was published under the “Seabright” name was the presence of another St. Clair story in the same issue in the essay. 🙂

Sorry…was reading into the wee hours last night and missed that!

Hi Rich. Thanks for writing about Margaret St. Clair/Idris Seabright, who has become one of my favorite authors from that period. One question about the use of Idris Seabright as a pen name by Margaret St. Clair. I rather assume she or the editors of F&SF wanted to brand or differentiate her stories in F&SF under that name starting with “The Listening Child” in 1950, which was her first F&SF story. Did you ever find any direct evidence of this, or other explanation of the use of that pen name? Thanks.

Hi Rich.

I’ve been on a Margaret St. Clair reading binge. You mention her last story published as “La extraña tienda” [Spanish] (1990), as by Idris Seabright, per ISFDB, published in “Antología del horror y el misterio 4”, Tomás Doreste editor, 1990 Grijalbo. You suggest this was probably a reprint.

At the website https://tercerafundacion.net/biblioteca/ver/ficha/7084, it is indicated that this story was a translation of “Graveyard Shift”, feb 1959 as by Idris Seabright . I recently read and loved “Graveyard Shift”, which is features a story of the supernatural at Bloom’s Sportsman’s Emporium, which does match with the suggested translations you suggest of “…’The Strange Store’ or perhaps ‘The Mysterious Shop.’”

I am going to suggest to ISFDB that this is a variant of “Graveyard Shift”, and we’ll see how I do. I have not been able to find a copy of “Antología del horror y el misterio 4”. Although I don’t speak Spanish, it would be more convincing perhaps to be able to look at the text and try to re-translate some of it and compare.

Thanks for the name suggestions.