The Odyssey of Guy Davenport

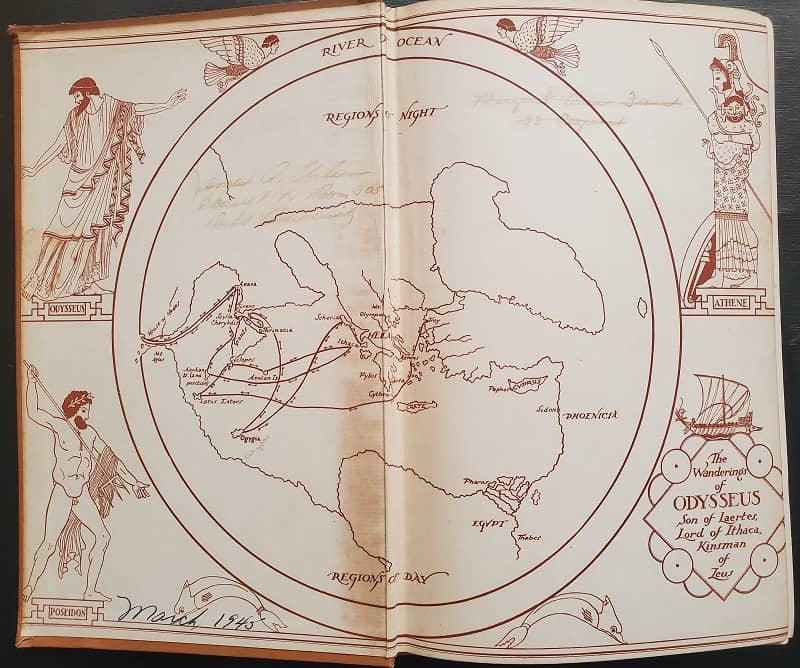

Inside cover of The Odyssey of Homer by TE Shaw (1945),

showing the wanderings of Odysseus

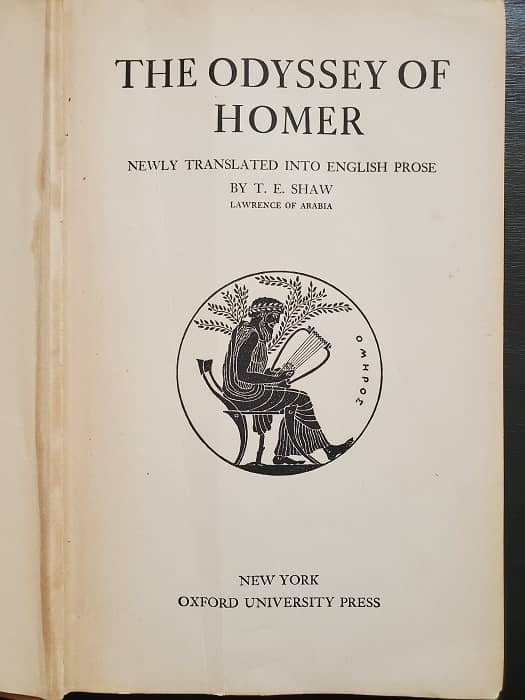

I bought a book last week from a bookseller on Instagram, the first time I’ve ever done that. It was a copy of T. E. Shaw’s translation of Homer’s Odyssey. Yes, that T. E. Shaw, Lawrence of Arabia.

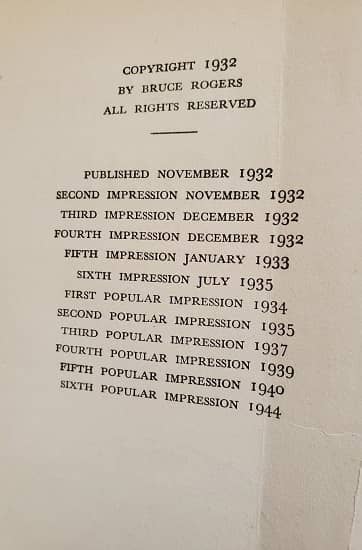

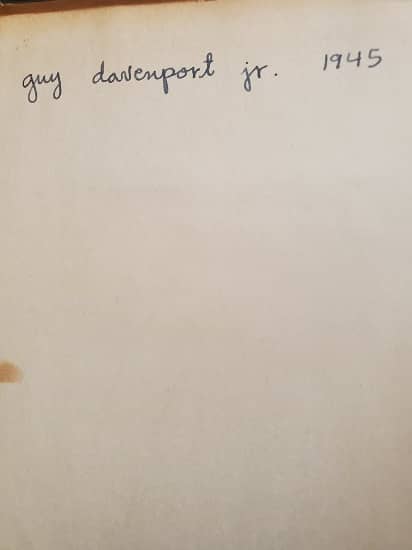

The book is old, beat, and tired. It’s probably a twelfth printing, depending on how you count such things, but what caught my attention was that the seller had included a photo of the previous owner’s signature, Guy Davenport, Jr., and the signature was dated 1945.

Did this copy of the book belong to Guy Davenport, a minor but very interesting science fiction writer who won a MacArthur fellowship in 1990? I bought the book and then started to research.

I’ve found nothing conclusive, but everything points in that direction. Davenport was named after his father Guy Mattison Davenport and was, in fact, a Junior. Davenport would have been 18 years old in 1945, just the right age to read the book in either his first year of college or his last in high school. He taught for 27 years at the University of Kentucky and lived in Kentucky for another 15 years until his death in 2005, so the book turned up in the correct geographical location.

[Click the images for bigger versions.]

|

|

|

Cover, publication data, and inscription in the TE Shaw volume

So who was Guy Davenport? I’d barely heard of him until I had dinner one night with the writer Hal Duncan and a prominent French editor at a science fiction convention a number of years ago. Duncan claimed that Guy Davenport was his favorite author, which I and the editor found surprising.

Davenport was a translator, primarily of Greek texts, and a writer of short stories and essays. He was friends with Ezra Pound, who he met in 1950 while the poet was incarcerated for treason, but also with other writers such as John Updike, Dorothy Parker, and Joyce Carol Oates.

|

|

Title page, and detail from inside cover

So I’m happy with my little purchase. It appears to be a formative book once owned by an impressionable author-to-be. Is it valuable? Not really, although there must be two or three Guy Davenport collectors out there somewhere.

Postscript: The seller, @readwritebooks_forsale, tells me that he bought the book as part of a larger lot from a woman he now believes to be Guy Davenport’s daughter. He had never heard of Guy Davenport, though, until I enquired, as I’m sure that neither had many of you. I’d barely heard of him myself. A few whispers, really. A very occasional story in a magazine or in an anthology. He appears never to have desired to become a commercial novelist. And yet like Avram Davidson and R. A. Lafferty his stories continue to sputter in and out of fashion, a legacy for all, if we would only reach and grab it.

Nice find Jacob. Such a backstory.

On a somewhat obtuse note, Fritz Lerber’s Our Lady of Darkness novel has a similar, albeit far more sinister, experience of the books protagonist purchasing a diary that he discovers belonged to Clark Ashton Smith.

Davenport also studied philology under Tolkien. He considered Tolkien a mumbling, pedantic professor and had trouble reconciling this image with Tolkien with the writer of The Lord of the Rings, which he greatly admired.

Here’s one of the columns I’ve written for Beyond Bree, the monthly Tolkien newsletter. The “Days of the Craze” columns focus mostly on the 1965-1969 period that begins with The Lord of the Rings in American paperbacks and ends with the Ballantine Adult Fantasy Series, by which time “fantasy” was well established in the American publishing world. This column is (c) Dale Nelson.

Days of the Craze No. 29: Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner

By Dale Nelson

Some interesting bits for Tolkien fans may be gleaned from Questioning Minds: The Letters of Guy Davenport and Hugh Kenner, two volumes edited by Edward M. Burns (Berkeley: Counterpoint, 2018). Davenport and Kenner were learned men of letters, both interested in the Modernist poet Ezra Pound.

Davenport (1927-2005) was a student of Tolkien’s during his 1948-1950 period as a Rhodes Scholar at Merton College, Oxford. He wrote to Kenner (1923-2003) in Feb. 1963, “Have arrived at end of the Tolkien first volume. Wish I’d known about it earlier. Only valid resuscitation I know of material Brittonum, elves, hobbits, dwarves, that world. The Renaissance ‘working up’ in Malory and Spenser is too ornate, out-of-touch, prettified, embroidery. I’m amazed at Tolkien’s ability to manage it all without sentimentality. And talk about invention!” (p. 261).

In March he wrote: “Finished Tolkien’s trilogy [sic] yesterday: a major work. What imagination! Never does his invention run out, on and on. I have a feeling that he has summed up 500 years of literature: from the Mabinogion through von Essenbach to the High Victorians. He has done well in prose what Spenser probably could not have finished in verse. It makes the ‘realistic’ novel look like a skinned knee criss-crossed with bandages” (p. 287). Davenport finds LotR possessing “majesty,” unlike anything written since before the time of Cervantes. In a June letter, Davenport finds that a color photo of Ezra Pound and his daughter Mary reminds him of the “returned king of Minas Tirith and a princess of the Rohirrim” (p. 348). In October, he sees William Morris as a “Pre-Tolkien Tolkien” in The Earthly Paradise (p. 420); half a dozen years later, Ballantine Books would be marketing Tolkien much the same way in its series of fantasy reprints.

Davenport was acquainted with Walter Hooper (he speaks of “C. S. Lewis’ secretary and literary executor”) and hoped that, through Hooper, he could see Tolkien during a trip to Oxford (to Kenner, 13 May 1964; p. 601). Kenner replies, the next month: “I envy you Tolkien, if accessible” (p. 606). Davenport’s 24 Oct. 1964 letter mentions his slide photo of Tolkien’s house (“roses and an apple tree”) but says nothing about the professor.

However, National Review – William F. Buckley’s magazine – published Davenport’s “The Persistence of Light” in its 20 April 1965 issue, and, in this review of Tree and Leaf, Davenport, “drawing on his acquaintance with Tolkien, writes that [Tolkien] can be seen every day on the streets of Oxford, ‘a man in his seventy-third year, philologist, professor of English literature, pipe-smoker, a touch of un-English in his dress, with the requisite eccentricities.’ He also describes Tolkien at his home on Sandfield Road[;] ‘behind a perfectly English gate, apple tree and rose trellis, he puts down on paper, in English as clear and flexible as Chaucer’s – and, like Chaucer’s, equally true to the nature of miller, knight, oaf, king, or animal – stories as fascinating as any ever told in the world” (Questioning Minds p. 748, citing page 332 of the National Review article). Davenport disliked the article’s illustration, of “two children drawing aside bushes to reveal Tolkien in his garden” (pp. 707, 748).

Let’s pause over this April 1965 National Review article for a moment. In the United States, Ace Books released an unauthorized paperback edition of The Fellowship of the Ring the next month, with The Two Towers and The Return of the King appearing in July, igniting the Tolkien Craze. This means that, when the Craze took off, Davenport’s piece was a rare periodical article with something to say about the man as he was then. “Persistence” must have been a much-looked-up piece as high school and college students and others combed The Reader’s Guide to Periodical Literature to track down information about this exciting author with the peculiar name.

Speaking of names, in his 17 May 1966 letter, Davenport crows about discovering a “clan of Proudfoots over near Butterfly, Kentucky” (p. 795; see also p. 1395). Davenport eventually published pieces suggesting Tolkien derived some hobbit names from someone who told him about Kentucky, but David Bratman has spurned this notion in an article published in Tolkien 2005 Proceedings: The Ring Goes Ever On, Vol. 2 (pp. 164ff.).

Davenport was author of the obituary of Tolkien published in National Review (28 Sept. 1973), his last piece for the magazine (p. 1602). His last Tolkienian remark in a letter suggests that he found the just-published Silmarillion unreadable (p. 1669).

I’ve omitted a few of Davenport’s incidental references to Tolkien’s creations. He was, like Peter S. Beagle,* one of the people who published articles on Tolkien just on the threshold of the Tolkien Craze.

*See my “Days of the Craze No. 4: Taking Tolkien Cross-Country by Motor-Scooter” in Beyond Bree March 2012, page 1.

Jacob, I wholeheartedly recommend Davenport’s collection of essays, THE GEOGRAPHY OF THE IMAGINATION. Lucid, illuminating, wonderfully entertaining. Worth the price of admission for his reconstruction of the writing of OZYMANDIAS alone. And on a minor note, the reason for the title of my own A GEOGRAPHY OF UNKNOWN LANDS.

Also, if any of those books have marginalia in Davenport’s hand, they are of interest to scholars and fans. Chip Delany, for one.

This is indeed Guy Davenport’s signature.

The woman who sold this and other books was probably Bonny Jean Cox, now deceased, who was a close friend and became Guy’s literary executor. Davenport had no children.

There are indeed Davenport collectors, of whom I am one.

This book of yours may be of interest to the University of Texas’s Harry RansomHumanities Research Center, which purchased what was supposed to have been Davenport’s entire home library. They took possession of his notebooks and home library after his death. Cox was supposed to have included everything, but it is known that she did not.

Not only did Davenport take a course in Old English from Tolkien, while at Oxford he also met the mother of Lawrence of Arabia. Details about Davenport’s extraordinary career can be found at his Wikipedia page.

I had the privilege of editing and helping to print his last limited edition, a restored text of the novella that he thought was his best shot in fiction. See http://www.guydavenport.com. Cheers! You have a truly great find, there. Will it to Harvard (where Davenport got his Ph.D or to the University of Texas Harry Ransom Research Center.

Is there any chance you would sell this treasure? If so, I would love to buy it. I was a student of Guy’s when I was an undergraduate at the University of Kentucky and he meant a lot to me. I still read his essay on translations of the Odyssey (called ‘Another Odyssey’ and collected in Geography of the Imagination) when I need to hear his authorial voice.

I recently found this exact signature in a book that must be from his personal collection (?) He wrote “Guy Davenport Jr 28 Nov 1947” in an old pelican edition on modern architecture. This is the only blog/comment section I can find with info.

Hi Savanna. Guy Davenport, Jr. is better known without the Jr.. As plain Guy Davenport he was very successful in several professions. I’d recommend starting with his Wikipedia page and branching out from there.

I had an offer to sell the book a few years ago, but the buyer had a sudden reversal of fortune. But yes, even though I’ve enjoyed the book I might be willing to part with it.