An Evocation of the Science Fiction Dream of Exploration: “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany

|

|

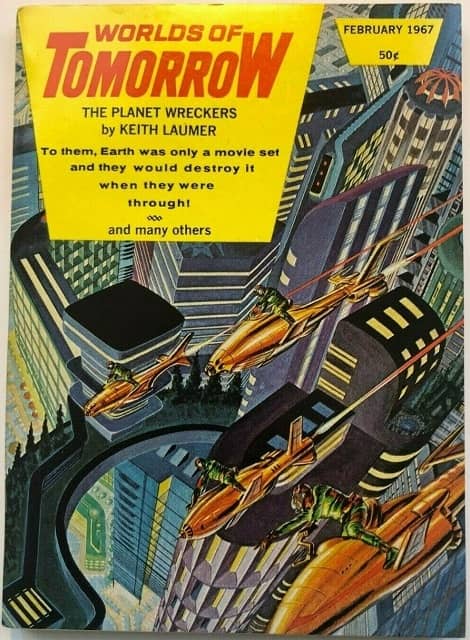

Worlds of Tomorrow, February 1967, containing “The Star Pit” by Samuel R. Delany. Cover by Morrow

This is the first of what I hope will be an extended series of essays taking a closer look at some stories I either consider to be particularly good, or interesting for other reasons. Of necessity, each of these essays will go into some detail as to the plot of the stories – in most case, in my opinion, this will not “spoil” the stories, but I know that I am less spoiler-phobic than many, so tread carefully.

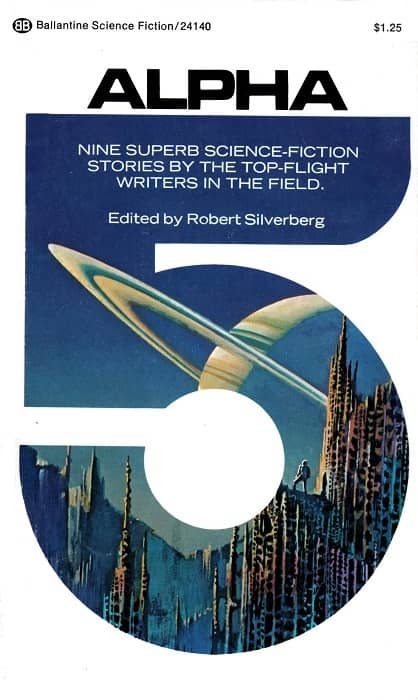

I remember reading “The Star Pit” as a teen, probably in Robert Silverberg’s exceptional reprint anthology Alpha 5. It was a story I liked then, and loved on a reread a few years later. I remember it as one of the great underappreciated novellas in SF. But it’s been quite a few years since my last read.

In fact this is a story with a decent history of anthologization and recognition over the years, so my term “underappreciated” is off base. It first appeared in Worlds of Tomorrow for February of 1967 – and as Worlds of Tomorrow was widely considered the “third-string” magazine in Fred Pohl’s editorship, behind sister magazines Galaxy and If, that could be regarded as “underappreciation,” though more likely it reflected the difficulty of fitting novellas into magazines. (Interestingly, the magazine ceased publication after the next issue (May 1967) before a brief (three issue) revival in 1970 and 1971.)

“The Star Pit” was a finalist for the 1968 Hugo for Best Novella, which went in a tie to “Riders of the Purple Wage” by Philip Jose Farmer and “Weyr Search” by Anne McCaffrey. It was in Judith Merril’s SF 12, the very last outing for her seminal series. Robert Silverberg anthologized it twice – not just in Alpha 5 but in the Arbor House Treasury of Great Science Fiction Short Novels. Gardner Dozois put it in his anthology with a similar title (and ambition) to Silverberg’s: Modern Classic Short Novels of Science Fiction. And Richard Lupoff chose it for What If? Volume 3, the third entry in his series of books highlighting the stories that he felt should have won the Hugo each year. (Unfortunately, the What If? series was cancelled after the first two books, and Volume 3 only appeared decades later from a small press.)

|

|

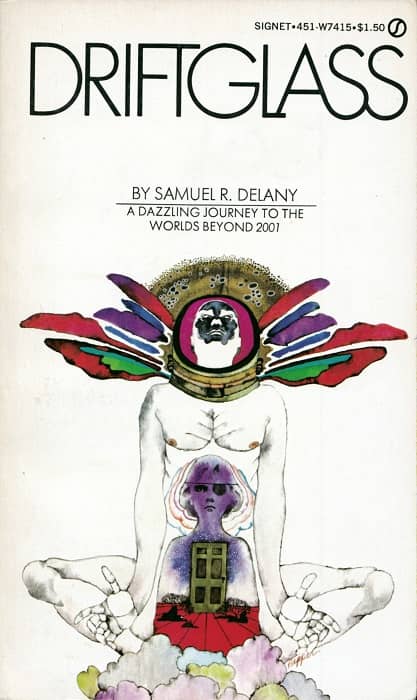

Alpha 5 (Ballantine 1974, cover by Bruce Pennington) and Driftglass (Signet 1977, cover by Bob Pepper)

Delany collected “The Star Pit” in his great first collection Driftglass, and in a later collection, Aye, and Gomorrah. I sometimes wondered why the story wasn’t in an Ace Double as other Delany novellas like Empire Star were, but it did get a reprint in the Tor Double series much later, backed with John Varley’s “Tango Charlie and Foxtrot Romeo.” I think it was clearly the best novella of 1967, and I think it’s fair to say that Dozois, Merril, and Lupoff agreed with me. (We can’t ask them, alas, as they have all died – but at least Gardner and I commented to that effect in Jo Walton’s Informal History of the Hugos.)

I have just reread it, in the very same copy of Alpha 5 I originally bought early in 1975. And it maintains its status as a great story. It’s long been obvious to me that Theodore Sturgeon was a major influence on Delany (as I believe he has often acknowledged) and I think this might be his most Sturgeonesque story.

The Star Pit/Tango Charlie and Foxtrot Romeo (Tor Double, 1989). Covers by David Lee Anderson and Tony Roberts

It’s told by Vyme, a 40ish starship mechanic working in the “Star-Pit,” a huge structure at the edge of the Galaxy, from whence intergalactic ships depart. But we don’t know that for a long time, as he tells of his earlier life, specifically a time period on another planet when he was part of a group marriage (or “procreation group.”) The group’s children make an “ecologarium,” sort of a large terrarium, and we see the alien life in the “ecologarium” go through its lifecycles, within its enclosure. Meanwhile Vyme leaves their home occasionally, for mechanic jobs across the local area of the Galaxy. Also, he has a drinking problem. And he remembers his childhood on out-of-the-way Earth, confined in an apartment, Earth people mostly confined to their “primitive” planet.

But I’m forgetting something. Well, no I’m not — because it is only some way into the story that we learn one crucial thing. Humans are confined to our Galaxy. Some distance out of the Milky Way, people go insane, then die. Except for one class of people, discovered fortuitously: the golden. These people are psychotic, but in a specific way that makes them able to bear the stress of intergalactic travel. They are not superhuman — they have no other particular powers, and in fact Vyme believes them to be both stupid and mean. It’s not clear if the stupidity and meanness stems from their psychosis, or from the way they are set apart from the rest of humanity, or is Vyme’s jealousy of them. (Though we do see the golden do some stupid and mean things.)

Vyme’s drinking eventually reaches a point where he feels he should leave the proke group for good. Not long after that their planet is destroyed in a war. And Vyme fetches up at the Star-Pit, gets himself clean, and eventually owns his own shop. As the main action of the story (but main action? It’s all main action!) starts, Vyme has one employee, Sandy, who has also had to leave his family, but who hopes to get back to them. Another young man — or, that is, boy — Ratlit, 13 years old, is working at the shop of Vyme’s friend and sometime lover Poloscki. Ratlit’s a bit of a mess — grew up rough, can’t read but wrote a bestselling novel, did time, etc. And Ratlit hates the golden … but it’s clear he envies them too. He has a lover, Alegra, a 15 year old girl who is a drug addict and a projecting telepath.

Two things drive the rest of the action — a golden, Androcles, comes to the Star-Pit to work, then kills another golden, which means he claims the dead golden’s ship. Which he gives to Sandy, who wants no part of it. Sandy wants to go back to his family, but it becomes clear they want nothing to do with him. Then Alegra is diagnosed as golden. But she’s dying. And Ratlit wants nothing more than to take a starship and leave the Galaxy… and now there’s a ship, and a golden’s ID belt…

|

|

SF 12 (Dell, 1969, cover by Paul Lehr), and What If? Volume 3 (Surinam Turtle Press, 2013, cover by Gavin L. O’Keefe)

Where does this leave us? You can all probably guess how it ends, and you probably know Vyme is still at the Star-Pit, wanting to get out but knowing he can’t, maybe wanting another family but feeling he can’t be trusted. Sandy is stuck too. And Androcles reveals something that suggests the golden are just as stuck in their own way.

What is this story about? The most obvious key is the replicated ecologaria — from the ant farm Vyme had as a kid to the huge ecologarium Vyme’s kids had to the tiny one full of microscopic creatures that Androcles wore around his neck. All represent interconnected communities, that grow and change but can never leave their container. And so, is the Galaxy an ecologarium most humans can never leave? Is the universe an ecologarium even the golden can’t leave? That’s powerful and moving, but I don’t think it’s all.

One thing we learn about the ecologaria is their complete interconnectedness. In a way, Vyme suggests, they are like a single organism. Is their purpose reproduction? Is someone who’s disconnected from that role damaged? And by “role” I don’t mean just being a genetic father or mother but part of a “family” — hence the large proke groups, where all the adults are parents. So — Vyme is damaged, because he left his family. Sandy too, because he was kicked out of his. Alegra is seriously damaged, and in the end loses her child as she dies. And the golden — the golden are kicked out of the family too. They can’t have children with each other, and the children they do have are taken away to be made golden. And they leave the Galaxy — the “home” — and are psychically damaged. Are they the real victims?

All of them are broken people — all these characters — and we care for all of them. And how to fix them — us? And what of our urge to explore — to leave — to go to a place we’ve never been? Is that wrong? Or is it a tragedy that it can’t be made right? But right at the end, I think Vyme nails it for us. What is critical for an organism, or a species, or an entire ecology? Reproduction, yes – but also growth. And the story does show us this as well – we see Vyme grow (a lot), and we see his children grow (but alas they die) and then his surrogate children, like Sandy, and Ratlif, and Androcles – some grow, perhaps some fail. Also humanity is growing – it has left explicitly primitive Earth and occupied the Galaxy. But it can’t leave the Galaxy … except for the golden.

Aye, and Gomorrah (Vintage Books, 2003). Cover by Yukimasa Hirota

And, so, Vyme’s final insight is that in some way the golden are humanity’s children – immature, certainly, as we are shown (and I had a thought – probably misplaced – that the golden might be named in reference to the feral supermen in Philip K. Dick’s “The Golden Man.”) At the end Vyme, while mourning his dead children in drunken laughter, asks “what better way to launch my live ones who are golden into night?”

This is a story I love, and how does Delany do it? Part of it of course is his image-drenched prose. And behind it is the somewhat implausible but inspiring evocation of the traditional SFnal dream of exploration, enhanced here with the view from the Star-Pit and the description of the alien planets and tech. This is somewhat sketchily described but there’s enough to suggest the wonder behind it – but always from the point of view of trapped, working-class, Vyme, which makes it stick better than the POV of a star-conquering emperor.

But most of all the structure, the interlocking tales of Vyme’s childhood, his time with his children, and with his surrogate children at the Star-Pit, and the interlocking descriptions of the various ecologaria: the ant farm, the large structure his children build, the tiny necklace Androcles wears. There is destruction everywhere (and this Galaxy seems perpetually war-torn), but there is also the hope for growth.

Rich Horton’s last article for us was “Edith Wharton, Jean Cocteau, and an Ancient Mesopotamian Tale,” directed by John Litchen. His website is Strange at Ecbatan. Rich has written over a hundred articles for Black Gate, see them all here.

A great story, certainly, and if it’s not exactly underappreciated, I think Delany himself is perhaps slipping into that category, which is often the fate of revolutionaries who help bring about changes so far-reaching that they render those who wrought them invisible.

“The Star Pit” remains one of my very favourite stories.

What a wonderful coincidence, Rich, that you wrote this article only a month before I picked up the Tor double on a whim in a thrift store during a road trip through Tasmania. I was floored by the beauty and insight of this story and immediately reread it, and have spent the morning looking for commentary to help me coalesce and articulate my feelings about this amazing story that does everything i want sf to do, esp the way it foregrounds the human and keeps the technological mileu in the background. I have never read any delany before, but i am now a fan for sure and will be seeking out as much as i can find. (Side note: i did pick this up after noting Joanna Russ’s mention of Delany in her intro to “We Who Are About To…” and, well, that seems to have worked out for me!). Thanks again – Hope you and yours are well and safe.