A Potent Draught of Distilled Fairy Fruit: Lud-in-the-Mist by Hope Mirrlees

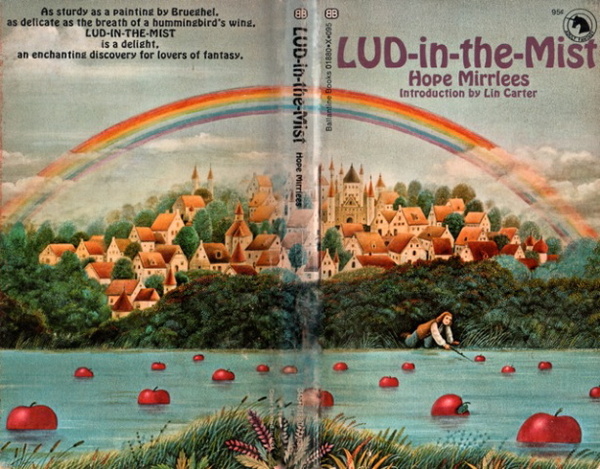

I’m back with a new column. Each first Friday of the month I’ll be writing about a work of fantasy I’ve never read (or read only once a long time ago; I insist on room for maneuvering!). Because of Lin Carter’s magnificent taste, it may at times seem I’m simply going through titles from his Ballantine Adult Fantasy series, but my goal is to rummage around in the basement and attic of fantasy, exploring works that preceded, or exist outside of, modern commercial fantasy. My reach will extend at least as far back as the Gothic novels first appearing in the late 18th century, and I hope it will come forward to today. So far, my planned reading includes Gormenghast, The Last Unicorn, Once Upon a Time, The Ship of Ishtar, Melmoth the Wanderer, and Frankenstein. If all goes well, I’ll even go for The Worm Ouroboros and The Manuscript Found in Saragossa, too.

Fantasy has become a successful commodity. Witness the gargantuan force of A Song of Ice and Fire, both in print and on the screen. And what are the leotard-clad protagonists of superhero movies but updated versions of the heroes panegyrized by the skalds and griots? Fantasy, to which I’ve dedicated untold numbers of hours reading and writing about, is more successful than I could ever have imagined forty-odd years ago when I first read The Hobbit, and yet I’ve found my taste for it diminishing with each passing year.

Excellent and original work is being created, but you have to hunt for it. Most new fantasy simply mimics ideas already done to death a long time ago, bringing nothing new or substantial to the field. I love the Ramones, but after four or five albums, you’ve heard everything they have to say. I feel the same way about new fantasy. And yet, I still find myself drawn to fantasy, remembering how it’s allowed me to shrug off the bonds of reality and slip into the world of dreams. I just don’t want another thousand-page story exploring the magically-augmented struggle for the throne of some imaginary kingdom, or a supposedly realistic disquisition on power politics in a “grittier” analogue of the real world, or about how there really isn’t good and evil, only gray morality. Even my beloved sword & sorcery begins to seem a little wan after reading eighty or ninety stories a year. Only in the best of hands do I find new stories that still hold my interest.

I recently reread Mikhail Bulgakov’s The Master and Margarita, a tale of the devil visiting Moscow, a writer and his lover, and a novel about Pilate and Christ. While a serious novel about art, love, and totalitarianism, it’s also fantasy. The form allowed Bulgakov to explore ideas he might not, under Stalin, have attempted otherwise (and still it was censored until decades after his death). Some of the deepest, most affecting scenes are pure fantasy, drawing on myth and nightmare instead of psychology and our five senses, allowing them to find a way to our soul that a realistic version could not. Bulgakov wrote to satisfy himself, not the dictates of the market. And though there’s nothing wrong with the latter, the result will rarely be a Bulgakov. You won’t encounter another book like The Master and Margarita because it wasn’t written to conform to genre considerations. Bulgakov never set out to become a “fantasy” writer, just a writer who would find the best way to tell the stories he wanted to tell.

I’m also in the middle of rereading The Lord of the Rings. Less overtly literary than Bulgakov, nonetheless Prof. Tolkien used fantasy as his framework to create myths, explore weighty concepts like bravery and self-sacrifice, and along the way tell great tales of adventure. His works are also permeated by an almost overwhelming atmosphere of loss, precipitated by greed and self-interest far more insidious than any dark lord. Unlike the standalone nature of Bulgakov’s novel, LOTR is almost easily imitable, at least from a technical aspect. And yet most of those imitations are dim shadows, focusing on adventure, neglecting big ideas, and rarely singing instead of talking.

I bring up TMaM and LOTR as examples of what I want from fantasy: creative works that serve as more than occupiers of my time, that are written with themes my soul hearkens to. I want fantasy as idiosyncratic and as believed in by its creator as Bulgakov’s or Tolkien’s. It’s not fantasy I’ve given up on, just most genre fantasy.

Until recently, I’d only read discussions of Ursula K. Le Guin’s 1973 essay, “From Elfland to Poughkeepsie,” but never the thing itself. I find she was pointing out fifty years ago much of what’s been eating me today. “Elfland” is a warning that fantasy can easily become a lesser thing when practiced mostly for profit or, worse yet, without real imagination and skill. In fact, it’s the latter she takes more issue with, building her essay on a snatch of dialogue from one of Katherine Kurtz’s Deryni books. Done with the best of intentions but “a refusal to admit what you’re in for when you set off with only an ax and a box of matches into Elfland,” the result is a work that easily allows the transposition of a story from Elfland to Poughkeepsie without any differences. For her, it was a concern of stories written like journalism, not poetry.

This is not meant to be a putdown or a restrictive definition of fantasy. I like fantasy – a lot. That’s exactly why I’ve spent so much time with it over most of my life. There’s no more exciting reading for me than sitting down with Robert E. Howard or P.C. Hodgell. Unfortunately, Sturgeon’s Law — ninety percent of everything is crap — is as true of new fantasy writing as it is of anything else, and much of the remaining ten percent doesn’t appeal to me. Having lost my taste for the greater share of what’s new, I’m going back in time, to the books I’ve missed or neglected. The first of these is Lud-in-the-Mist (1926), the sole fantasy novel by Hope Mirrlees.

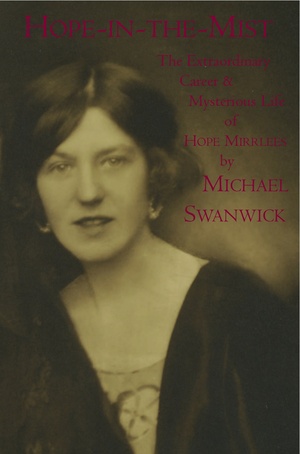

Hope Mirrlees (1887 – 1978) was the daughter of an Anglo-South African industrialist. She spoke Zulu, attended the Royal Academy of Dramatic Art, and studied Greek at Cambridge. There she formed a close bond with Jane Ellen Harrison, classicist and linguist. Whether their friendship was romantic or not is unknown, but they remained together until Harrison’s death in 1928 at the age of 77. During her life, Mirrlees wrote two minor literary novels, poetry, including a 600-line modernist work “Paris: A Poem,” and, the only thing she’s really remembered for, the fantasy novel Lud-in-the-Mist. According to her biographer, Michael Swanwick, “She knew all the intellectual lights of her time, flitting inconsequently through the lives and sometimes biographies of Gertrude Stein, Bertrand Russell, Andre Gide, Lady Ottoline Morrell, Anthony Powell, Walter de la Mare, Katharine Mansfield, William Butler Yeats, T.S. Eliot.” (Here’s an interview with Swanwick about Mirrlees)

In her diary, Virginia Woolf (whose Hogarth Press published “Paris: A Poem”), described Mirrlees thusly:

Before this I met Hope Mirrlees at the Club — a very self conscious, wilful, prickly & perverse woman, rather conspicuously well dressed & pretty, with a view of her own about books & style, an aristocratic & conservative tendency in opinion, & a corresponding taste for the beautiful & elaborate in literature…. She uses a great number of French words, which she pronounces exquisitely; she seems capricious in her friendships, & no more to be marshalled with the long good wand which I can sometimes apply to people than a flock of bright green parrokeets.

With her friend’s death, Mirrlees, at the age of 41 and supported by the trust her father had set up for her, largely withdrew from the intellectual world of which she had been part. When Lin Carter decided to republish Lud-in-the-Mist in 1970, he made an unsuccessful effort to discover if she was still alive. She was, it turns out, living until 1978, but it is unknown if she ever knew her book was back in print. It’s a shame to think she never knew of the joy and inspiration — to Neil Gaiman, in particular — her novel bestowed. And it deserves to be better known and read today.

Briefly, once upon a time the land of Dorimare, from its capital, Lud-in-the-Mist, was ruled by increasingly erratic nobles and a state-sponsored priesthood. Dorimare’s last duke, Aubrey, under the influence of the neighboring Fairyland, proved intolerable and the merchant class, most put out by the duke’s indecencies, finally rebelled. Over “three days a bloody battle raged in the streets of Lud-in-the-Mist, in which fell all the nobles of Dorimare. As for Duke Aubrey, he vanished — some said to Fairyland.” The delusion of fairy was replaced with the delusion of law — both play “fast and loose with reality – and no one really believes” in them, but the former was seen as for the “cozening and robbing of man,” while the latter “was to his intention and welfare.” By law, Fairy and all its emblems were pronounced non-existent. Eventually, the “greatest insult one Dorimarite could hurl at another was to call him “Son of a Fairy.”” Centuries have passed, as the novel opens, with no contact between Dorimare and Fairyland. Now someone’s been smuggling fairy fruit into Dorimare and has been feeding it to the children of the land’s stolid merchants. Eventually, Lud-in-the-Mist’s mayor, Nathaniel Chanticleer, finds himself forced to become the hero of the hour, sacrificing his reputation, and possibly his life, to save his own son and Dorimare itself.

Unlike the doughty and vigorous heroes of so many tales, Chanticleer is stout and middle-aged. Though he has prospered in a land dedicated to good profit margins, creature comforts, and predictability, he has been cursed since youth with a tinge of melancholy for which he has found no cure, and which rises up and whelms him in unexpected moments. It goes back years, to an incident when he and his friends pulled a prank:

Well, when they had whitened their faces with flour and decked themselves out to look as fantastic as possible, Master Nathaniel seized one of the old instruments, a sort of lute ending in the carving of a cock’s head, its strings rotted by damp and antiquity, and, crying out, “Let’s see if this old fellow has a croak left in him!” plucked roughly at its strings.

They gave out one note, so plangent, blood-freezing and alluring, that for a few seconds the company stood as if petrified. …

He was never the again the same man. For years that note was the apex of his nightly dreams; the point towards which, by their circuitous and seemingly senseless windings, they had all the time been converging. It was as if the note were a living substance, and subject to the laws of chemical changes — that is to say, as that law works in dreams. For instance, he might dream that his old nurse was baking an apple on the fire in her own cosy room, and as he watched it simmer and sizzle she would look at him with a strange smile, a smile such as he had never seen on her face in his waking hours, and say, “But, of course, you know it isn’t really the apple. It’s the Note.”

This spiritually discombobulating event was to fill Nathaniel with “a wistful yearning after the prosaic things he already possessed. It was as if he thought he had already lost what he was actually holding in his hands.” No longer did he want to become a ship’s captain freely roving the seas rather than the prosperous owner of the whole Chanticleer fleet. Instead, he became deeply attached to the shops, streets, and people of Lud-in-the-Mist, though this was rooted as much in secret fear of uncertainty about the future as in fondness. He is known, though “not quite deserved,” as “a warmhearted, sympathetic man.” But actually, he is unsatisfied and frightened that the world beneath his feet is somehow lacking fundamental substance and might just crumble away one day. He is a man who finds solace among the tombstones, reading their inscriptions and wishing he might lead the lives described of their inhabitants.

When their young son Ranulph begins acting strangely, culminating in an outlandish outburst at a party, Nathaniel and his wife, Marigold, find themselves turning to the disliked Doctor Endymion Leer. The physician quickly diagnoses the boy as having somehow eaten fairy fruit. Despite any misgivings Nathaniel has about Leer, he wholly commits to his son’s cure. When it is recommended that Ranulph be sent to the countryside for rest, his father agrees.

Unfortunately, the sojourn does little to help Ranulph. At the same time, the number of incidences of people partaking of smuggled fairy fruit in Lud increases, despite the best efforts of the city guards. Nearly the entire student body of Miss Primrose Crabapple’s Academy for young ladies goes missing following a demented dance class. The long separation between Dorimare and Fairyland is coming to an end. Only Nathaniel Chanticleer is able to rise to the moment and save the day. Before the tale’s end, he must uncover the smugglers, solve an old murder, and ride into the frightful heart of Fairyland, populated by spirits of the dead, to save Ranulph.

Lud-in-the-Mist is about the need for creativity and sensuality, not just the mundane and commercial. Without them, life, as it has become in Dorimare, is sterile and, more than predictable, rote. While she describes only Nathaniel hearing “the Note,” it is clear other citizens of Dorimare have heard a similar thing. There is an emptiness in the people of the realm that can only be filled by the passion and creativity Mirrlees portrays as fairy fruit. Nonetheless, fairy fruit can be dangerous. Madness and addiction, even murder, are possible side effects of Fairlyland’s crop. For two centuries Dorimare has rejected the goal of balance in favor of abnegation. What now?

Neil Gaiman has called Lud-in-the-Mist the “great English fantasy novel.” If not the great, it is one of the greats. Mirrlees masterfully created a true secondary world that one can practically hear and smell. In Nathaniel Chanticleer she presents a person we all know — proudly successful, questioning the real value of his wealth, fearful that his life lacks greater significance. He is a magnificent achievement, lacking in the physical attributes normally assigned heroes in fantasy works, more than making up for them by drawing from wells of courage, determination, and even playfulness he has kept sealed for much of his life. And his progress is described in sparkling prose of which Mirrlees never loses control.

Much more important is Mirrlees’ exploration of the need for both art and reason. She suggests that part of creativity arises from our conversations with the past; literally the dead in the book. It is in the graveyard that Nathaniel feels most at ease, communing with the previous citizens of Dorimare. For a people to thrive, both rationally and emotionally, they can’t just bury the past; pretend their history, with all its magic and miracles, customs and rituals, doesn’t exist.

Too often this sort of struggle is presented purely one-sided: art must win out over anything that reeks of conformity or repression. In Lud-in-the-Mist, as for Mirrlees presumably, creativity is a dangerous, wild thing. Given totally over to it, the rulers of Dorimare had become abominations. The merchants’ uprising was an understandable reaction. As with everything, though, it has gone too far, and some way back to the center needs to be found. In the end, it is an exemplar of Luddish probity that rises to the challenge.

I can only imagine what Hope Mirrlees might have done had she continued to write in this vein. Surely, it shouldn’t have taken until 1970 for Lud-in-the-Mist to be restored to print. Neil Gaiman has called it “the single most beautiful and unjustly forgotten novel of the twentieth century.” That’s a pretty big claim to make for any book, let alone a fantasy by a nearly minor member of the Bloomsbury Group. And yet, I think he is onto something. It moves effortlessly from history to mystery, and from travelogue to adventure. She uses evocative descriptions of the world, an unsettling atmosphere, and even comedy (I’ve neglected heretofore to tell you it’s a wryly funny book) to tell her story, and she makes it all work to perfection. I wish she had written more, but this alone makes Mirrlees worthy of such laud as Gaiman accords her. I haven’t enjoyed or been as surprisingly moved by such a book for several years now.

Unknowingly, I picked the perfect book to kick off this column. The very best, deepest fantasy is in conversation with the real world, as with Bulgakov and Tolkien. It may be humorous, adventurous, or serious (or all three), but the effort must be genuine, and Mirrlees’ was clearly that. This book is a potent draught of distilled fairy fruit that deserves to be read and read again.

Fletcher Vredenburgh writes a column each first Friday of the month at Black Gate, mostly about older books he hasn’t read before. He also posts at his own site, Stuff I Like when his muse hits him.

Nice insightful piece, Fletcher. I’ve been meaning to read this for a while, so maybe now I actually will?

Fantasy was my first love, but even back in the Seventies and Eighties there seemed to be a finite amount of high quality work, all of it pretty old. Moorcock was the only contemporary fantasy writer I’d have put in the same pantheon as Howard, CAS, Tolkien, Peake et al. I’m kind of allergic to epic fantasy – I’m not even a big LOTR fan to be honest, although I love ‘The Hobbit’ – which may have been a factor. So I ended up reading a lot of Science Fiction, which I found more consistent in terms of quality. Or maybe I just approached it with different expectations.

@Aonghus – Thank you! I like some epic fantasy – definitely because I’ve chased after that rush I first got from LOTR (I’m in the middle of rereading it right now). As to sci-fi, I just don’t read that much of it anymore, but, when I do, I definitely have different expectations as well and I find myself far less disappointed. I’m not sure I’d say sf’s qualty is higher, but I’m more forgiving if it’s got big ideas or a certain sort of “it looks cool.”

Great piece, Fletcher. I’m looking forward to more.

I think it’s true that the greatest fantasies (certainly the ones that mean the most to me) were written before fantasy was a really even a distinct genre, but was instead a mode for eccentric expression. Books like the Gormenghast Trilogy, The King of Elfland’s Daughter, The Well at the World’s End, The Worm Ouroboros, The Circus of Doctor Lao, and of course Lud-in-the Mist have little in common with the commodified cookie cutter “fantasies” that fill the shelves these days.

Lud is a wonderful book and deserves to be more widely known. I especially love it because it features fatherly love and sacrifice, not the most fashionable topic these days.

@Thomas – Ah, Doctor Lao, I hadn’t even thought of that. I only read once years ago, so I can’t add to my list.

Well, Fletcher, some guy already did a pretty good BG piece on The Circus of Doctor Lao…at least you liked it – you were the only person to comment on it!

https://www.blackgate.com/building-a-world-in-a-vacant-lot-the-circus-of-dr-lao/

Lud-in-the-Mist and The Master and Margarita are two of my favorite fantasy novels. Excellent writeup!

Many women writers of that era who had long-time female companions were rather chary about publically admitting that they were Lesbian. (Examples include Willa Cather and Octave Thanet.) On occasion I find their protestations plausible (Ivy Compton-Burnett, for example, always angrily denied that she and Margaret Jourdain slept together, and she was eccentric enough I’d believe anything!) but in most cases I suspect they were simply concerned about their public reputation. (In a couple of cases — Cather for one, perhaps also Vernon Lee — I wonder if they might have identified as trans men were they alive today. I hasten to add that that is sheer brazen speculation on my part, and they may well have angrily denied such an identity.)

I meant to write CAN. ?

So good to see a sympathetic review of Mirrlees’ classic. I read it many years ago, when it was first republished by Lin Carter and then again a couple of years ago. Although I enjoyed it as a teenager, I think I only really appreciated its subtle delights on the rereading. Can I suggest that you have a look at The Hearing Trumpet by Leonora Carrington. A bizarre but wonderful end of world piece that will either leave you indifferent or irritated or enthusiastic, like me!

@Neilh – I’ve never heard of her, but I looked her up and she sounds fascinating, as do her books.

The singular non-success of the Ballantine Adult Fantasy imprint was its devotion to genuine, one-of-a-kind fantasy works like Lud-in-the-Mist. The ginormous break-out of fantasy was the Del Rey imprint realizing that many readers want “comfort food”, “more of the same” works like The Sword of Shannara. Ian Ballantine was especially underwhelmed by the Del Rey approach to fantasy.

@Eugene – I need to go through the various forwards Carter did for the series to try and get a better understanding of why he chose what he did. Whatever his reasons, it remains one of the grandest undertakings (and achievements!) in publishing. I don’t know how many people he thought would actually read William Morris’ fantasies, but he must have thought some would, reflecting an amazing faith in his audience.

For me, the books that Lin Carter chose for the AFS remain the fundamental “syllabus of fantasy”, even when I don’t care for an individual volume or two. (The Shaving of Shagpat, anyone?)

@Thomas – It sure seems that way. As to Shagpat, I haven’t read it, but it’s sitting there on the shelf looking all tantalizing.

You go right ahead, Fletcher. I’ll stay outside the cave, holding onto the rope. When I hear you scream, I’ll pull like hell!

Lin Carter wrote a book called Imaginary Worlds as a kind of companion to the adult fantasy series. It is a history and guide to classic fantasy.

NYTRB is publishing a new edition of Leonora Carrington’s The Hearing Trumpet in January 2021.

Thank you for this interesting and informative piece. I have linked to it in my own review of Lud-in-the-Mist https://substack.com/@withthefairies/note/p-158825580