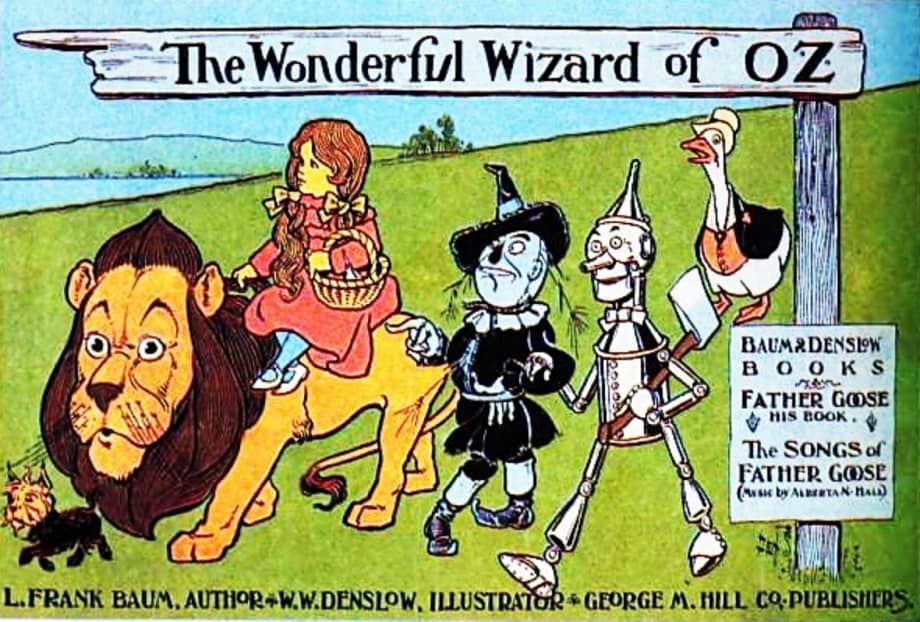

L. Frank Baum’s Oz Series: #1 The Wonderful Wizard of Oz

If we were to look at the roots of American fantasy, or even world fantasy, the writer L. Frank Baum’s influence looms large in the pre-Tolkien era. The 1939 MGM The Wizard of Oz movie is an indelible part of world culture. Canvas for impactful movie villains and the Wicked Witch of the West tops most people’s lists. The movie is so pervasive in culture that we can forget the source novels, though.

The Wonderful Wizard of Oz, published in 1900, sold 3 million copies by 1956, when it entered the public domain. Baum wasn’t keen on sequels, but the fan mail from kids proved to be a powerful pressure and he ended up writing 14 Oz books before his death in 1919. Then the publisher hired Ruth Plumley Thompson to write another 21, and some other writers came later.

I’d of course seen the movie as a child and received the third Oz book (Ozma of Oz) from a classmate in grade six. I hadn’t known that the movie was based off of books, nor that there was a vast narrative mythology in prose form. I read Ozma of Oz and was charmed with the creativity, the tone, the promise of many more adventures, and began picking up other books as I encountered them.

If you’d like to read along, many of the books are in the public domain, so ebooks are available for free download at The Gutenberg Index, or in audio at Librivox. Librivox has several versions of each novel, so feel free to give a quick listen to each version to pick the volunteer reader you like best before downloading.

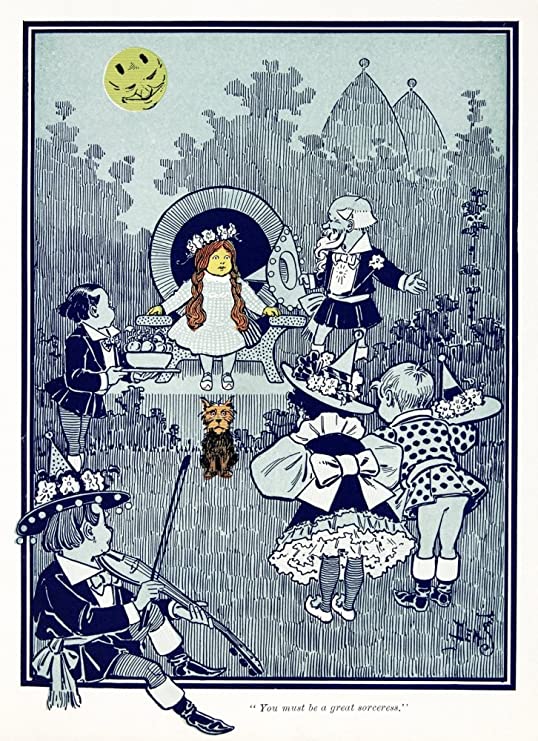

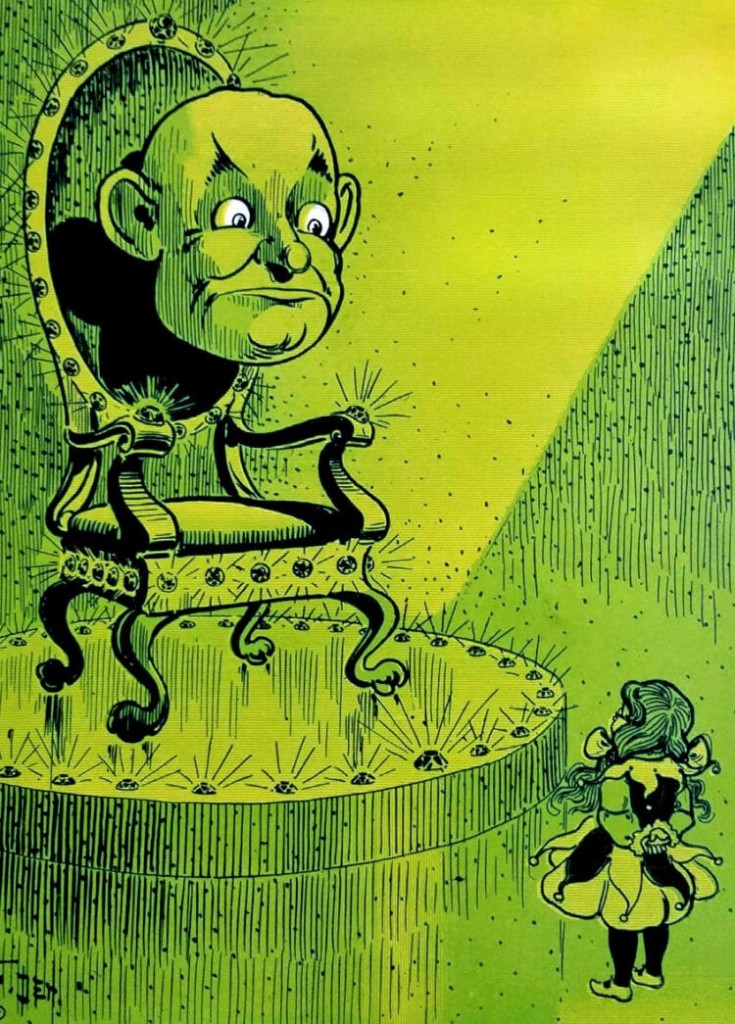

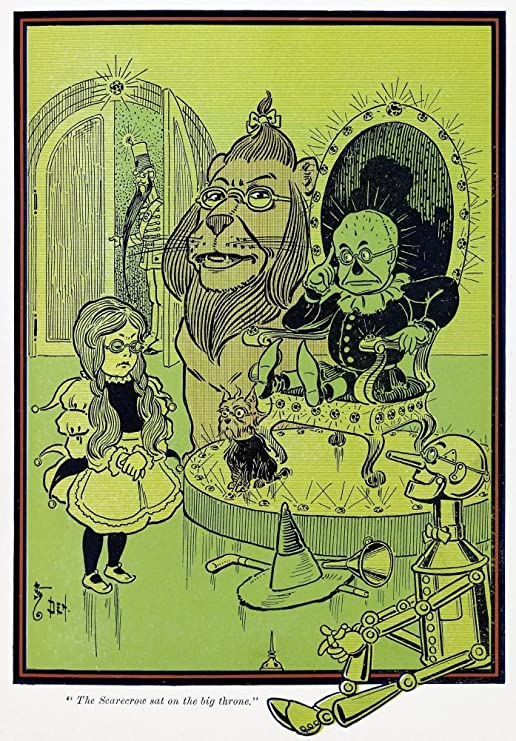

From our vantage point in 2020, it’s hard to separate what a ground-breaking novel The Wonderful Wizard of Oz was, in part because we’ve had the movie for 80 years. All of the fantastic world-building found in the movie was in the book first. The tornado, the magic slippers, the good witch, the munchkins, the yellow brick road, the Scarecrow, the Tin Woodman and the Cowardly lion, the Wicked Witch and the humbug Wizard, the flying monkeys and the final balloon mishap all come from the book.

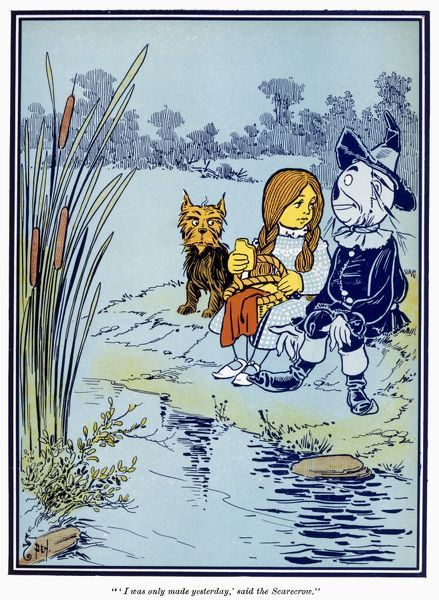

But the movie cut out some fun stuff. The first is some of the character development and the irony. The book spends a lot more time showing that the Tin Woodman is actually kind, and that the Scarecrow is actually coming up with ideas, and that the Lion is facing his fears, but telling us that they are heartless, brainless and cowardly respectively. The four characters form much more of an ensemble cast in the novel, while the movie is more certainly the Dorothy Gale story, and the Mrs. Gulch part at the beginning was a creation of the movie.

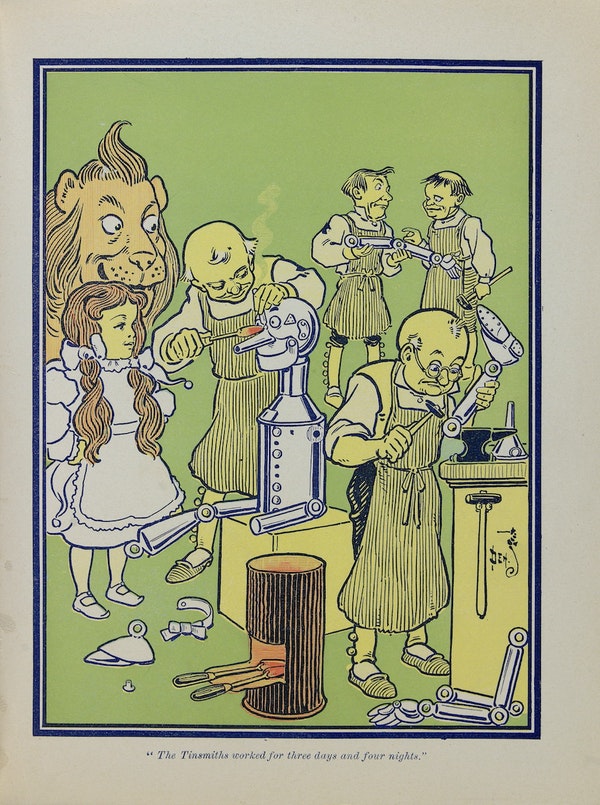

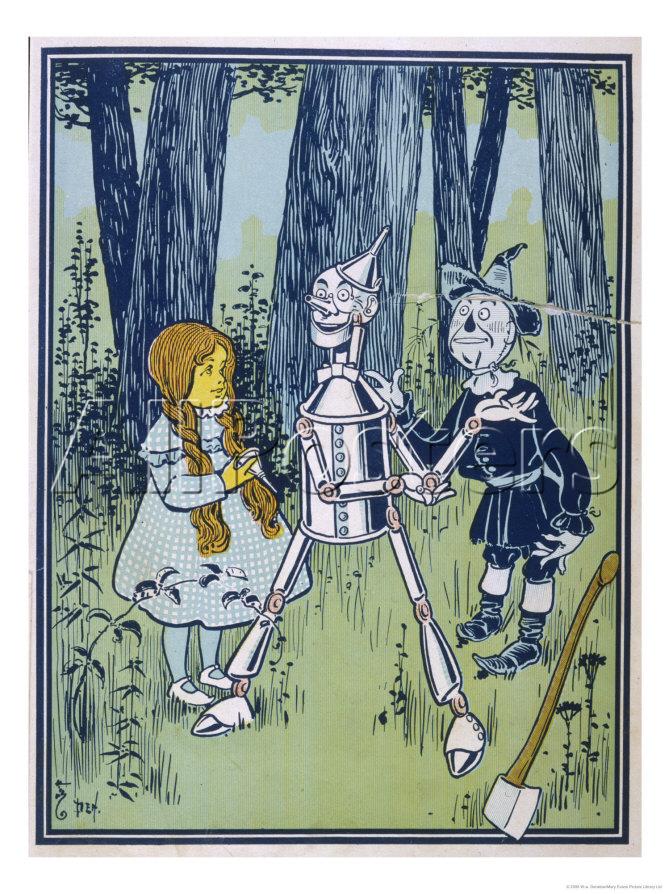

In a book of a slightly different tone, the work of the tin smiths soldering the Tin Woodman could be downright terrifying, but everyone in the image below is smiling, so all is good.

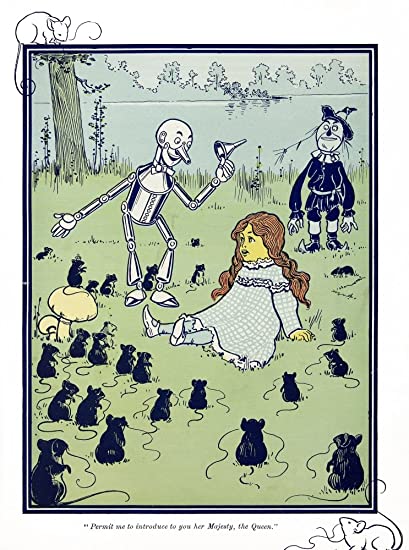

The adventure is also longer in the novel. There is a village of china dolls, help from some field mice when they are trapped in the poppy fields, a friendly stork who makes a deus ex machina save of the Scarecrow, and some really weird hammerhead people.

The sheer amount of art in the book and the way Baum and his publisher thought of the artist as a contributing creator feels a little like the way comic book creatives work together.

I brought the first two Baum books to my niece (with whom I read Moon Girl and Devil Dinosaur last year) during a socially-distanced visit and we’ve been reading them by videoconference, a little bit each night and it’s a lot of fun to go back to the book. My son (now 15) is getting into it too; we listened to the audiobooks when he was younger.

Check it out for yourself or a younger loved one in the family!

Derek Künsken writes science fiction in Gatineau, Québec. His first novel, The Quantum Magician, a space opera heist, was a finalist for the Locus, Aurora and Chinese Nebula awards. Its sequel, The Quantum Garden was an Aurora finalist as well. His third novel, The House of Styx, got a starred review in Publishers’ Weekly and the Library Journal and is out in audio and ebook (order link); and the hardcover will release in April, 2021.

I read an Oz book every year. (I have the DelRey paperbacks that were published – what, thirty years ago?) Baum’s invention never flags, and there are so may great character that weren’t in the movie because they appeared in later books. The Woggle Bug (who I imagine sounding like W.C. Fields) and the Nome King are my especial favorites.

I read all of these to my current 5-year-old last year. I agree with you that there is a lot of ingenuity in these works. They astound me! And when I got to Ruth Plumly Thompson’s contributions, I appreciated Baum himself so much more! The contrast is too noticeable.

I love the Del Rey editions, Thomas. The covers are great, but I love the trade paperback sized ones too, with the move classic art on them. I’m now into Book 2 with my niece.

Hey Gabe! I read a couple of Ruth Plumly Thompson’s books in high school, but haven’t since. I remember them being charming and maybe different too, but with a paucity of Baum books in my small town, I couldn’t be choosy. I’m looking forward to seeing what things look like when I get to her stuff again.

Great piece, here. This is a simultaneous blast from several pasts. I loved the first 2 as a kid–read them over and over again in old editions that my mom read in the 30s. I read through nearly the whole series with my son (mostly in the Ballantine paperbacks which we acquired one by one in the lost, lamented Uncle Hugo’s Bookstore).

I felt like the quality dropped off in the later volumes, although there’s some fun stuff in each one.

Thanks James! It’s interesting that you have multiple pasts, and generations. Neither of my parents are native English speakers, so I wasn’t exposed to Baum until it fell into my lap, but between my son and my niece, I’m inserting it into the family history now and I expect that my son would read it to his kids (when that day comes).