Fantasia Extra: Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin

For my last Fantasia post of 2020, I’m again going back to cover something I was too fatigued to get to in a previous year. In 2017 publisher Spectacular Optical put out Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin, a collection of essays by women scholars. The book launched at Fantasia and I asked for a pdf, then was too wiped out after the festival and for some time beyond to write a review. Although the book’s currently sold out, I’m reflecting on it now for three reasons. The first is simply because I dislike yielding to fatigue permanently. The second is that I think it’s worth writing a bit about Rollin, who I had not heard of in 2017, who does not seem to have been previously mentioned on this web site, and whose films of the fantastic are (to judge by this book) worth covering here. The third is to consider more generally the experience of reading about film, especially films one has not seen.

For my last Fantasia post of 2020, I’m again going back to cover something I was too fatigued to get to in a previous year. In 2017 publisher Spectacular Optical put out Lost Girls: The Phantasmagorical Cinema of Jean Rollin, a collection of essays by women scholars. The book launched at Fantasia and I asked for a pdf, then was too wiped out after the festival and for some time beyond to write a review. Although the book’s currently sold out, I’m reflecting on it now for three reasons. The first is simply because I dislike yielding to fatigue permanently. The second is that I think it’s worth writing a bit about Rollin, who I had not heard of in 2017, who does not seem to have been previously mentioned on this web site, and whose films of the fantastic are (to judge by this book) worth covering here. The third is to consider more generally the experience of reading about film, especially films one has not seen.

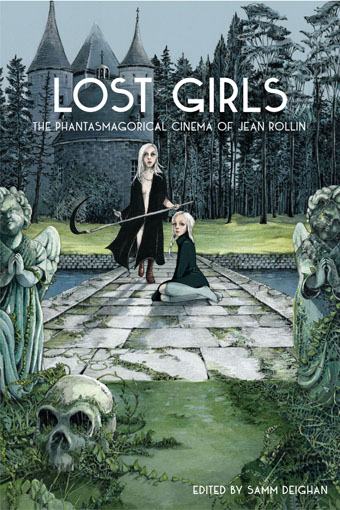

Let me start with Lost Girls. Edited by Samm Deighan, it’s 437 pages long, with a foreward, 16 essays, and an afterword. The tone’s academic but still accessible to a general audience — there are references and lists of works cited, and a general interest in placing Rollin within a broader cultural and intellectual context, but the essays tend to avoid the intricately theoretical and recondite. The book’s lavishly illustrated, with stills from Rollin’s films sometimes sharing a page with text they’re illustrating, and at other times assembled into two-page spreads.

Given the nature of Rollin’s work, there’s a lot of blood and nudity in the pictures. From this book and what I’ve read elsewhere I gather that while Rollin made low-budget films across a number of genres he’s best known for a cycle of movies in the 70s that combined horror, erotica, and arthouse surrealism. Ostensible exploitation films had their genre conventions undermined by ambiguity and mythopoeic imagery. Women were leads, heroes and villains and both in one; thus the idea of a book about Rollin by women, examining a male filmmaker whose work was ostensibly gazing upon often-nude young women but who also gave those characters unusual agency and range.

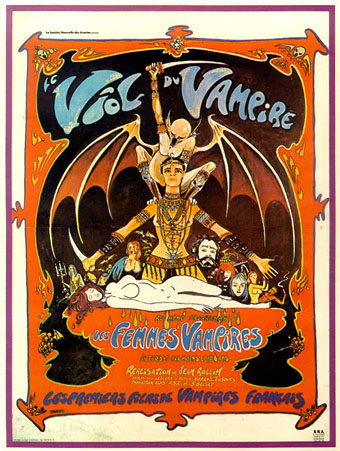

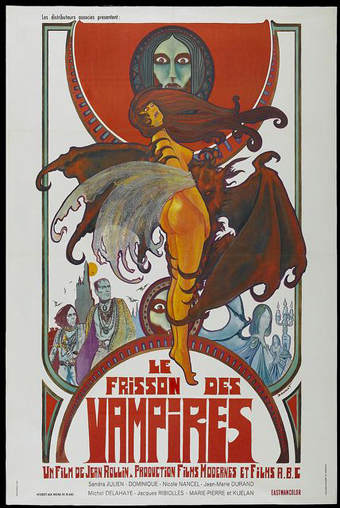

The essays in Lost Girls are generally respectful of Rollin. The book moves in a roughly chronological arc across his career, perhaps focussing especially on his early vampire films: Le viol du vampire (The Rape of the Vampire, 1968), La vampire nue (The Nude Vampire, 1970), Le frisson des vampires (The Shiver of the Vampires, 1971), and Requiem pour un vampire (Requiem For A Vampire, 1971). Recurring imagery in Rollin’s films is considered, as are his influences from the serial form, and fable-like or fairy-tale characteristics of his stories.

Most interesting to me personally are the different creative and intellectual traditions in which the essayists place Rollin. The first two essays establish influences discussed across the book. First, Gianna D’Emilio’s “Le Viol Du Vampire and the Last Surrealist Riot” notes that Rollin’s first movie was one of the few in Parisian theatres during the riots of 1968, and examines Rollin’s deep indebtedeness to the Surrealists, demonstrated not only by the images he created but also his approach to plot. Similarly, the next essay, Kat Ellinger’s “Cults Of Decadence, Cults Of Rebellion: La Vampire Nue and Fascination” considers Rollin as part of the tradition of the Gothic, placing him in a lineage going back to John Milton with particular emphasis on Victorian occultism and the diabolism of Anton Szandor La Vey.

Most interesting to me personally are the different creative and intellectual traditions in which the essayists place Rollin. The first two essays establish influences discussed across the book. First, Gianna D’Emilio’s “Le Viol Du Vampire and the Last Surrealist Riot” notes that Rollin’s first movie was one of the few in Parisian theatres during the riots of 1968, and examines Rollin’s deep indebtedeness to the Surrealists, demonstrated not only by the images he created but also his approach to plot. Similarly, the next essay, Kat Ellinger’s “Cults Of Decadence, Cults Of Rebellion: La Vampire Nue and Fascination” considers Rollin as part of the tradition of the Gothic, placing him in a lineage going back to John Milton with particular emphasis on Victorian occultism and the diabolism of Anton Szandor La Vey.

Other essays focus on settings in Rolin’s work; thus Alison Nastasi’s “Love Among the Iron Roses: The Cemetery as a Romantic Nexus in the Films of Jean Rollin” and Virginie Sélavy’s “‘Castles of Subversion’ Continued: From the Roman Noir and Surrealism To Jean Rollin,” the latter of which reflects on the ways the history of castles that appear in Rollin’s films inform his narratives. Other essays more directly consider the ways Rollin presents women (for example, Samm Deighan’s “Blood Sisters: Female Intimacy in Jean Rollin’s Contes De Fées”) or rape (Erin Miskell’s “Manifestations In the Physical Plane: Rollin, Rape, and the Effects Of Sexual Assault”), or place his films in the context of genre (Marcelle Perks’ “‘Final Girl’ Strategies In Les raisins de la mort, La nuit des traquées, and Les paumées du petit matin”) or Rollin’s overall career (Deighan’s “Phantasmes: Jean Rollin’s Hardcore Reveries and Work For Hire”). I don’t want to slight those pieces. But for me, introduced to Rollin through this book, the pieces describing Rollin by describing his images and stories in a context with other work were more intriguing.

(I will note that the essays don’t interrogate the gender binary much, and while that likely derives from the nature of Rollin’s films, it felt like a surprising omission. I will also note the occasional error of fact; a mention, for example, of “[Ann] Radcliffe’s cursed monk Ambrosio,” which I think should properly refer to Matthew Lewis’ character from The Monk. Or a reference in the context of the 1970s to “the titular character in Marv Wolfman’s comic book Blade,” when in fact Wolfman introduced Blade in Tomb of Dracula — with art by Gene Colan and Tom Palmer — before giving him some stories in Vampire Tales and Marvel Preview; Blade didn’t get a title of his own until the 1990s. These are quibbles, but occasionally jarring.)

The idea of Rollin’s work this book presents — not just in its texts but through the stills — is a weird dreamy otherland of graveyards and castles, of grandfather clocks and the stony beaches at Dieppe, of clowns and mists and blood and masks and flowing robes. There’s an odd wonder that comes from reading books about films you’ve never seen, particularly illustrated books; your mind works on the descriptions, as though constructing a dream out of the details you’re given. That’s especially true in this case, with a filmmaker consciously working in a Surrealist tradition, who built plots that were more allusive than logical.

The idea of Rollin’s work this book presents — not just in its texts but through the stills — is a weird dreamy otherland of graveyards and castles, of grandfather clocks and the stony beaches at Dieppe, of clowns and mists and blood and masks and flowing robes. There’s an odd wonder that comes from reading books about films you’ve never seen, particularly illustrated books; your mind works on the descriptions, as though constructing a dream out of the details you’re given. That’s especially true in this case, with a filmmaker consciously working in a Surrealist tradition, who built plots that were more allusive than logical.

For all that I’ve never seen a Rollin film, I enjoyed reading this book quite a bit. The idea of Rollin that emerges is intriguing, and the idea of the films even more so. There’s a tone the essays establish that’s not quite like anything else I’ve seen. I have no idea if it matches the actual experience of watching one of Rollin’s film, but it’s quite effective in itself. Lost Girls has much to say in general about the history of vampires and horror film. But it’s maybe especially worth reading as a fine and strange example of what writing about film can evoke even in the absence of experience with its nominal subject.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

Didn’t know about this book, but I’m loving that cover art and so have discovered the art of Jessica Seamans and she’s done some other cool horror film art.

I have a soft spot for Rollin but I’ve never been sure quite how to rate him. It might seem to damn him with faint praise but one of the things I like best about him is what he doesn’t do. I love gothic horror but don’t get why such a strong visual style always gets utilized for the same rehashed stories and Rollin is a bit of a respite from that. None of that Hammer or Corman acting/dialogue (though I do like some of those), it’s quiet and minimalist; refreshing.

Some of his films seem a bit insubstantial or boring but I like Grapes Of Death, Shiver Of The Vampires, Lips Of Blood and The Iron Rose a fair bit.

Like I said with Jose Mojica Marins, Rollin also has a body of prose fiction, only one book in English I think, Little Orphan Vampires (a slim book and first of a series).

I never even heard of Rollin until a month or so ago. I ordered a boxed set of the 4 vampire films mentioned here, but they’ve been sitting in a postal warehouse in Tennessee for over 2 weeks. And the book is unavailable anywhere! I’ve tried 4 of my favorite book-search sources, besides Amazon and AbeBooks, all without luck, and eBay doesn’t even list it.

Rollin was perhaps the only one true genius among all the horror filmmakers. Over 50 years on, his films are like a breath of fresh air in a stale room that is horror movie genre. Nuff said, gotta keep on Rollin boys and girls