Fantasia 2020 Part XXXV: Three by Jose Mojica Marins

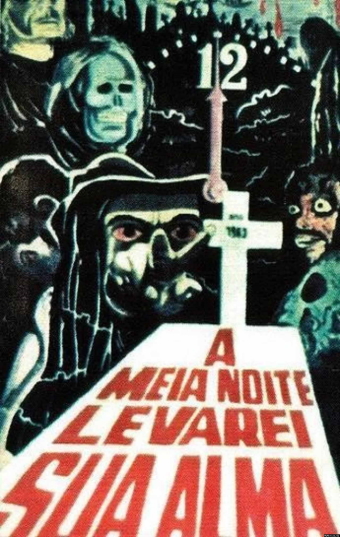

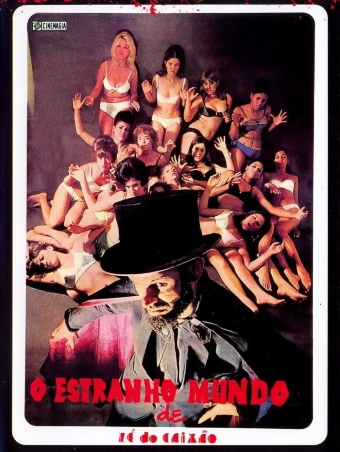

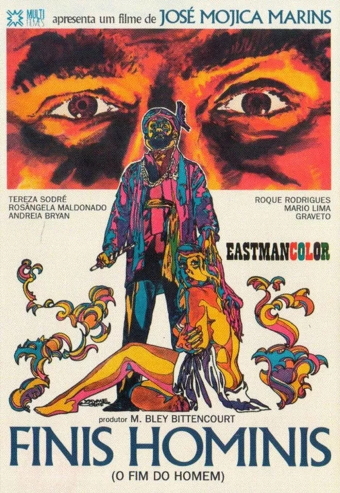

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival; you can watch the talk here. I, who had never heard of Marins before this year’s Fantasia, decided to remedy my ignorance by watching the three films they were hosting back-to-back-to-back: At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, 1968’s The Strange World of Coffin Joe (O Estranho Mundo de Zé do Caixão), and 1971’s The End of Man (Finis Hominis). They’re three very different movies, and together made a fascinating experience.

Brazilian director José Mojica Marins died earlier this year at the age of 83. He made low-budget films across a number of genres, with his horror work best known. His character Coffin Joe (Zé do Caixão), introduced in the 1963 film At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul (A Meia Noite eu Levarei sua Alma) is a kind of national ghoul of Brazil. Fantasia decided to honour Marins by making three of his films available on-demand through the festival, and scheduling a talk about Marins with his friend Dennison Ramalho on the last day of the festival; you can watch the talk here. I, who had never heard of Marins before this year’s Fantasia, decided to remedy my ignorance by watching the three films they were hosting back-to-back-to-back: At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, 1968’s The Strange World of Coffin Joe (O Estranho Mundo de Zé do Caixão), and 1971’s The End of Man (Finis Hominis). They’re three very different movies, and together made a fascinating experience.

What I’ve since learned about Marins from various sources: he was born in 1936 in São Paulo, and grew up making amateur 8mm and 16mm films. He released fumetti (comics with photos for illustrations), founded his own film company at 18, and in 1958 put out his first completed feature, a Western. He self-financed At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, which was based on a nightmare he’d had. Unable to find an actor for the lead role, Marins played it himself; he was already a striking figure, with fingernails grown out several inches, and for the film he added a beard, top hat, black cape and suit. Joe was an undertaker who grew obsessed with having a perfect son by the perfect woman, a character who threw overboard all morality and received ideas of good and evil in pursuit of his will — an explicitly Nietzschean monster. Joe was instantly popular in Brazil, returning in sequels and hosting horror TV shows. Marins would go on to make films in other genres until 2008, though (so far as I can tell) he remained on the margins of the Brazilian industry.

At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul is a black-and-white film in which we’re introduced to Joe, an undertaker in a small town, and follow him through a story of murder and rape in which he tries to father his ideal son. There is a fortuneteller who predicts a bad end, and a curse, a nasty bit with a spider, a climax in a graveyard at midnight. There’s an energy to the movie, and a definite fascination to Joe as a character — a monster in the gothic tradition, a human being who aspires to be something more than human.

The Strange World of Coffin Joe is an anthology film. The first segment, “The Dollmaker” (“O Fabricante de Bonecas”) gives us the story of an old dollmaker with three beautiful daughters; three youths plan to rape them, but their plans don’t work out as they expect. The second, “Obsession” (“Tara”), is a silent piece about a balloon seller who becomes obsessed with a beautiful woman; she is murdered, and he breaks into her tomb to violate her corpse. “Theory” (“Ideologia”) begins with an appearance on TV by controversial professor Oãxiac Odéz (played by Marins), who argues that humans are driven by instinct and not by intellect or by emotions such as love; this leads to a colleague and his wife, who disagree, being imprisoned and tortured.

End of Man is completely different from either of the others. The only colour film of the three, it follows a strange man (Marins) who walks out of the ocean and wanders about helping people, in a rough parallel with the life of Jesus. He adopts the name Finis Hominis, appears to raise the dead, and finally returns to where he came — an insane asylum. There’s an almost picaresque feel to this movie, a string of events that barely follow logically, a kind of surreal satirical psychedelia.

End of Man is completely different from either of the others. The only colour film of the three, it follows a strange man (Marins) who walks out of the ocean and wanders about helping people, in a rough parallel with the life of Jesus. He adopts the name Finis Hominis, appears to raise the dead, and finally returns to where he came — an insane asylum. There’s an almost picaresque feel to this movie, a string of events that barely follow logically, a kind of surreal satirical psychedelia.

Still, the three movies do have some similarities. They’re all done on a budget, obviously. But they also all have a strong visual sense. The black-and-white films in particular have some very strong imagery, but more than that, the visual storytelling’s powerful. The silent segment in Strange World highlights Marins’ sense of how to tell a story in images.

Conversely, the stories are all fairly simple. That’s not necessarily bad, and to an extent the directness of At Midnight is part of what makes it work. There’s certainly a melodramatic tone to all the films, a conscious attempt to make big statements about the world. That’s undercut to an extent by the simplicity of the big statements, but the ambition’s notable. Marins is making movies about a world without God, but he’s still got a God-shaped hole in his understanding of the world. There’s a sense of the world as a story that’s almost religious, except that in place of God we see figures setting themselves up in God’s place.

Which is to say that there’s a gothic sensibility in each of the movies. You see that the most in At Midnight I’ll Take Your Soul, which is often called Brazil’s first horror film. In fact there’s a mix of a lot of different kinds of horror story in that one, really. The small town terrorised by a monster recalls something of the Universal monster pictures. The weird energy, and the opening featuring the old fortuneteller crone speaking directly to the audience, is very like EC Comics. And the violence and fairly explicit rape is a little like Grand Guignol on film.

That’s even more true in the second film. Strange World is more transgressive, bloodier, much more violent. It’s also less interesting narratively. Marins clearly tries to be more philosophical, but the philosophy’s so simplistic it doesn’t really present much of an interest. Add to that acting that’s iffier than usual, and there’s not much to the film beyond Marins’ visual sense. I felt there was a slapdash feel to this movie, the closest of the three to the schlock films of Herschell Gordon Lewis. It’s not quite as bad as those — Lewis cared only about cranking out gore as cheaply as possible — but it’s also not that far off because the movie’s interest in exploitation overrides the minimal story. The extended final tale is effectively a series of tableaux depicting various tortures, and there’s just not much to it beyond that.

End of Man is clearly the strangest of all three films. There’s a slyer feel than the other two, Marins clearly in a mocking mood. I don’t know if it’s exactly more sophisticated than the others, but it’s odd, and engaging in a way that plotless movies of this kind usually aren’t. You don’t follow Finis Hominis as a character, because he has no character; so the movie tends to break down into a series of sequences, short stories, in some of which we follow other characters who Finis Hominis affects. And there’s definitely a sense of altered consciousness at work, as the fractured narrative moves from sequence to sequence according to an opaque dream-logic — associative rather than linear, if you like.

End of Man is clearly the strangest of all three films. There’s a slyer feel than the other two, Marins clearly in a mocking mood. I don’t know if it’s exactly more sophisticated than the others, but it’s odd, and engaging in a way that plotless movies of this kind usually aren’t. You don’t follow Finis Hominis as a character, because he has no character; so the movie tends to break down into a series of sequences, short stories, in some of which we follow other characters who Finis Hominis affects. And there’s definitely a sense of altered consciousness at work, as the fractured narrative moves from sequence to sequence according to an opaque dream-logic — associative rather than linear, if you like.

Marins is direct and confrontational in each of these films. There are voice-overs introducing the stories, and dialogue that establishes exactly what we’re supposed to think about what we’re seeing. At its best, his writing captures a kind of pulpy grandeur — again, a gothic sense, a feeling that we’re seeing characters who in going beyond conventional morality become quasi-diabolical. As though the unyielding desire to transgress gives the movies a kind of reverse dignity.

Which would mean nothing if not for Marins’ ability to pull that off as the central figure of these movies. In particular the image he projects as Coffin Joe is a visual complement to the monstrosity of the character’s ideology. There’s a Satanic undertone to Joe — and indeed Joe’s surname Zanatas is meant to be ‘Satanas’ backward. Stil, a demented undertaker, even one with an unusual fashion sense, doesn’t sound like much of a monster. But Marins plays him with such force of personality he comes across as something more. The drive to have a perfect son is an unusual one for a monster, but the fact Joe wants that son only as a function of his own self-regard makes the drive monstrous. The story of At Midnight sets him up as physically powerful and intimidating, and if that’s not something that makes sense on a plausible human level it means that means you have to interpret Joe as something on another level than the human. Joe comes off as a man who has access to some power beyond the common run of humanity, and knows it. Again, this is the Gothic anti-hero writ large.

Overall, the three movies gave a picture of a filmmaker with considerable natural gifts, compromised by low budgets, struggling to put across the things that mattered to him. Those things included a sense of the world diametrically opposed to received ideas of morality or religion. There’s a sense of glee in transgression, and a kind of forcefulness to the story construction. At their worst, those things result in tedious scenes of depravity that don’t develop ideas or much of a narrative. At their best, there’s a real power, visually and otherwise. Even moments of a crude sublimity. Uneven as the films were, I’m glad to know about Marins, and intrigued by his work.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.

I once got a box set with 8 or 9 of his films (one is a documentary) that came out here in the UK several years ago. Most of the films bored me out my skull but I quite like the first two Coffin Joe films and one or two others have their moments (I thought that “Dollmaker” segment was quite atmospheric and it hinted at some kind of monster it couldn’t have shown, because of budget).

I’d recommend you see the second Coffin Joe film: This Night I Will Possess Your Corpse (1967). I think it’s a bit better than the first film and people tend to remember the color segment in hell.

I did wonder if he had a coherent philosophy behind Coffin Joe or if translators of the films and the few interviews I’ve seen have maybe failed him.

I think he boasted that his bestiality comedy got women to have sex with their dogs and I remember one translator laughing in embarrassment at this.

He wrote a huge amount of fiction and comics so I’ve always wondered what he could do without the limitations of his small budget films.

I think some of his films were actually very successful and Glauber Rocha (an arthouse director) praised him for making popular films that resonated with Brazil (or something like that).

You’ve put me in mind to get a copy of Embodiment Of Evil.