Fantasia 2020, Part XXVIII: 2011

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

I’ve mentioned that many of the films I saw at this year’s Fantasia were haunted-house stories. Or: horror movies that revolve around a specific architectural location. That’s an intriguing coincidence in the year of COVID-19, but perhaps speaks to filmmakers finding a way to limit budgets and get the most use possible out of their locations. Which brings me to 2011, a film set in a single apartment and a kind of ghost story that begins and ends with the horror-thriller form. But this only becomes clear at the very end, for mainly this is an experimental and ambitious film that wanders through different genres and types of stories.

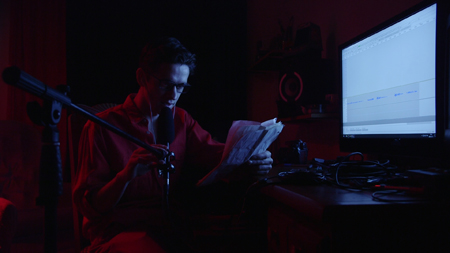

It’s the first movie directed by Alexandre Prieur-Grenier, from a script written by Prieur-Grenier with Maxime Duguay and Emmanuel Jean. An unnamed insomniac film editor (Émile Schneider), living in his Montréal apartment, works on assembling a movie called A Burning Flesh. As he does, different kinds of things happen to him, forming multiple plot strands out of which the film 2011 is woven. Bound up with these things are the editor’s dreams, and a grasp on reality that grows shakier as the film goes on.

To start with, there’s the mystery of the tenant next door, who may or may not be breaking into the editor’s apartment. This is the aspect that’s most dreamlike, and perhaps least certain. The apartment next door may be empty, or may not. There may be noise coming from it, or may not. This strand is central to the movie, but doesn’t develop in a linear way — the editor sporadically tries to investigate his neighbour, but there isn’t any sense of him getting closer to figuring out what’s happening in the other apartment through the film.

Instead much of the forward narrative motion of the movie comes from the development of the film-within-a-film the editor’s working on. The director, Hugo (an intense Hugolin Chevrette), visits repeatedly and they view scenes the editor’s put together. That movie’s elliptical, too much so for me to grasp its relevance to 2011 at one viewing. What is most narratively important is that the editor struggles to work on it and grows obsessed with an actress.

The editor in fact has a girlfriend as 2011 begins, but his romantic life also provides plot material. In addition to the two women already mentioned, after he spots a violent argument between his landlord and his wife (Tania Kontoyanni) the wife starts an affair with him. This is dangerous, as the landlord is a bruiser with a bad temper.

There’s a lot of story here, plus the inset scenes of A Burning Flesh, plus dream sequences, plus the editor’s work on a kind of mural decorating the entryway of his apartment. Reality breaks down, and a sense of physical threat grows. But the movie never quite resolves into a simple genre tale, in part because it doesn’t quite build any kind of story. There isn’t a sense of a structure developing, or even really of a character or characters driving events.

Usually, that would be fatal to a narrative film. In this case, though, the movie still works, in part, because it’s clearly and consciously trying to do things differently. The editor’s point of view holds the film together, as he’s pushed and pulled in different directions by the different stresses around him. By the end you can more or less understand what’s happening, and what the significance is of the next-door neighbour. You can appreciate the ambition, whatever you think of the result.

Usually, that would be fatal to a narrative film. In this case, though, the movie still works, in part, because it’s clearly and consciously trying to do things differently. The editor’s point of view holds the film together, as he’s pushed and pulled in different directions by the different stresses around him. By the end you can more or less understand what’s happening, and what the significance is of the next-door neighbour. You can appreciate the ambition, whatever you think of the result.

There’s also a very strong visual approach to the movie, which is almost entirely set in and around the one apartment (along with the scenes of the film-inside-the-film). It’s a standard Montreal apartment, but it comes alive as an odd place. The editor’s artwork, and his adaptation of his home into a film studio (and, at times, a recording studio), give it a distinct character. At its best, the movie’s a reminder of the individuality and even weirdness that can lie behind any given nondescript door in a nondescript apartment building.

Possibly related to that, I found the storylines involving the development of A Burning Flesh were the most interesting part of 2011. Part of that has to be that Hugo is the most dynamic character in the film, and Hugolin Chevrette makes a charismatic foil for Schneider’s editor. But it also felt like the film became the point of connection between the relatively everyday world, of the editor’s love affairs and conflict with his neighbour, and a stranger world of dream and art and possibly madness. (Of course you can’t overlook the fact that it’s also in a sense the storyline closest to the filmmakers’ lived experience — the movie was in fact shot across two years in Prieur-Grenier’s own apartment.)

All of this is to say that I found the movie fascinating, but not consistently engaging. I think the diffuse story is to some extent deliberate, but I suspect many viewers might find it unsatisfying. The lack of commitment to any one story or type of story flattens the material — lacking narrative development, the movie often threatens to turn into a series of things that happened instead of a work of fiction. For me, the development of A Burning Flesh gave 2011 a spine, but even then I’m not sure that thread was resolved as strongly as it might have been. Instead the subplot of the mysterious neighbour becomes the climax, and one that moves the film more thoroughly into the horror genre. But it’s really only after everything’s been said and done that we understand this.

All of this is to say that I found the movie fascinating, but not consistently engaging. I think the diffuse story is to some extent deliberate, but I suspect many viewers might find it unsatisfying. The lack of commitment to any one story or type of story flattens the material — lacking narrative development, the movie often threatens to turn into a series of things that happened instead of a work of fiction. For me, the development of A Burning Flesh gave 2011 a spine, but even then I’m not sure that thread was resolved as strongly as it might have been. Instead the subplot of the mysterious neighbour becomes the climax, and one that moves the film more thoroughly into the horror genre. But it’s really only after everything’s been said and done that we understand this.

I think 2011 works on the whole, as a small-scale low-budget experimental film that has enough story to it to keep a viewer watching. I also think it could have been written a little differently and maintained the experimental aspects while also structuring the story more powerfully — not necessarily more conventionally, but more coherently. As it is, 2011’s a fascinating document that seems to anticipate issues that many people must deal with in 2020: being stuck at home, working from home, dealing with neighbours, the mental stress of increasing isolation. It’s an intriguing film, and a promising one.

Find the rest of my Fantasia coverage from this and previous years here!

Matthew David Surridge is the author of “The Word of Azrael,” from Black Gate 14. You can buy collections of his essays on fantasy novels here and here. His Patreon, hosting a short fiction project based around the lore within a Victorian Book of Days, is here. You can find him on Facebook, or follow his Twitter account, Fell_Gard.